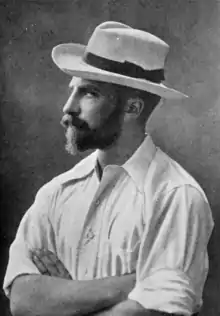

James Stevenson-Hamilton

James Stevenson-Hamilton (2 October 1867 – 10 December 1957) served from 1902–1946 as the first warden of South Africa's Sabi Nature Reserve, which was expanded under his watch and became Kruger National Park in 1926. The Tsonga people nicknamed him Skukuza because when he arrived at the area of the reserve he "turned everything upside down" with the banning of all hunting in the reserve and the relocation of all the native kraals.[1] Skukuza camp and Skukuza Airport is named in honour of Stevenson-Hamilton, who is regarded as a champion of wildlife Conservation in South Africa.

James Stevenson-Hamilton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 October 1867 |

| Died | 10 December 1957 |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Other names | Nicknamed Skukuza by the Tsonga people |

| Occupation | Warden, Kruger National Park |

Early life and military career

James Stevenson-Hamilton was born in Dublin, Ireland[2] on 2 October 1867 to Colonel James Stevenson-Hamilton and Eliza Hamilton.[3] As the eldest of nine children, he was the legal heir to the family title and home at Fairholm, near Larkhall in Scotland. He was educated at Rugby and Sandhurst and opted for a career in the military. He stationed himself briefly on the banks of the Crocodile River in South Africa, familiarising himself with the land and animals, but soon moved and settled at Sabi Bridge, which is now called Skukuza.

Following Sandhurst, Stevenson-Hamilton was commissioned into the British Army as a second lieutenant in the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons on 14 March 1888,[4] and saw active service with the Inniskillings in Natal later the same year.[5] He was promoted to lieutenant on 20 February 1890, and to captain on 1 June 1898,[4] the same year as he joined the Cape-to-Cairo expedition under the leadership of Major Alfred St. Hill Gibbons. After they had "Tried to steam up the Zambesi in flat bottomed launches and fought their way well beyond the Kariba Gorge",[6] they had to abandon their boats and explore Barotseland on foot. Stevenson-Hamilton then "trekked across Northern Rhodesia to the Kafue."[6] After the expedition, he returned to active service, and fought in the Second Boer War (1899-1901), receiving both the Queen's South Africa Medal and the King's South Africa Medal for his service. He also received the brevet rank of major on 29 November 1900 for his service in the war,[7] and after the end of hostilities was promoted to the substantive rank of major on 12 November 1902.[8]

History of the Sabi Nature Reserve

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger, commonly known as Paul Kruger, was the President of the South African Republic from 1883 to 1902. It was he who first pleaded "for setting aside certain areas where game could be protected and where nature could remain unspoilt as the Creator made it".[9] His vision, however, was not shared by other members of his parliament; his efforts to conserve land, especially in the areas between Swaziland and Zululand and in the Zoutpansberg area, met with strong opposition.

In 1891, Kruger managed to amend existing game laws, and the state started providing protection for some animal species. After managing to declare other smaller areas as game reserves, on 26 March 1898, he proclaimed the 'Goewerments Wildtuin' (Government's Reserve) between the Sabi and Crocodile rivers as the Sabi Nature Reserve.[10] After the end of the Anglo-Boer War (1902) and the death of Paul Kruger (1904), the reserve had almost been forgotten until Lord Milner re-issued the proclamation for the reserve.

Stevenson-Hamilton and the Sabi Nature Reserve

In June 1902, Sir Godfrey Lagden, the newly appointed Commissioner for Native Affairs in South-Africa, appointed James Stevenson-Hamilton as the first warden of the Sabi Nature Reserve, and he was seconded from the army to service for the British colonial office.[11] As a "bachelor, a man of means and a professional soldier,"[6] Lagden deemed him fit for the job even though the post was viewed as unusual and unheard of. Stevenson-Hamilton signed a two-year contract as warden, found a map of the area and set off with a wagon, oxen, provisions and ammunition for an uncharted and malaria-filled land described to him as the "white man’s grave".[10] Game-ranging was still a new term and this allowed Stevenson-Hamilton to have free rein over the Sabi Nature Reserve, his only order from Lagden being "to make himself generally disagreeable"[6] and to try to eliminate poaching. In 1902, he reached Nelspruit.

His first order of business was to announce that no shooting was to be allowed and that if he and his servant could live on tinned meat, so could the white men and natives who were inclined to shoot an impala whenever they felt the need. He believed "that if there were no shooting, if animals were left to live in the veld as they had lived before man came on the scene, they would lose their fear of human beings and flock to an area that had once been described as 'red with impala'".[6] He then moved his headquarters from Crocodile-Bridge to Sabi-Bridge and appointed two rangers, including Harry Wolhuter, and together they trained native rangers. Poachers soon realised that he was serious about the "no shooting" rule, and many were caught, "Including, on one occasion a party of senior policemen"[12] who were caught killing a giraffe and a wildebeest and were convicted and fined for their crimes.

After this, "what he did is now a matter of history. He trained his rangers, thinned out the lions and the wild dogs, declared war on the poachers and patrolled the whole area."[6] He also became the magistrate, customs collector and border guard, as well as watcher of the railway line to the south of the reserve.

His focus then went back to Johannesburg and Pretoria where he started to convince companies in the vicinity to lend him land, eventually giving him a huge block in a remote corner of Transvaal. By doing this, he created the space that is known today as Kruger National Park. Extending the reserve from the original 1,200 square miles (3,100 km2) to 14,000 square miles (36,000 km2). In this larger protected area, wildlife could roam freely from the Crocodile River to the Limpopo River.

In 1912, he first presented his idea for the nationalization of the reserve to then Minister of Foreign Affairs Jan Smuts. The idea was to transform the reserve into a national park, but to do this he needed "the support of the public, but to gain that support visitors should be allowed into the park".[10] Unfortunately, World War I temporarily halted these events. In 1926, Piet Grobler established the National Parks Bill in parliament as encouraged by Stevenson-Hamilton and presented Kruger National Park as a realization of the dreams of Paul Kruger. The Sabi Nature Reserve was officially renamed to Kruger National Park of South Africa. In 1927, the park was opened to the public.

Later life

Stevenson-Hamilton served the game reserve for 44 years from 1902 to 1946.[6] After his retirement on 30 April 1946, he settled in White River. At the age of 63, he married Hilda Chomondeley, 34 years his junior. They had three children: Margaret (born in 1931), James (born in 1933) and Anne (born in 1935).[13] He died on 10 December 1957 at the age of 90.

Legacy

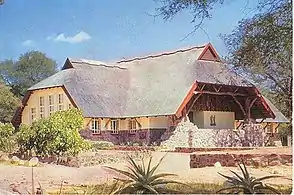

Stevenson-Hamilton was a good friend and fellow of the Tsonga people and he was dubbed "Skukuza" by the Tsonga who lived on the reserve, meaning 'the man who has turned everything upside down' or 'the man who swept clean'. This referred to his efforts to eliminate poaching in the reserve, and according to Henri-Alexandre Junod, also referred to the Tsonga people's attitude toward him after he had evicted them from the southern lowveld. Stevenson-Hamilton understood Tsonga language as well as Tsonga culture and was taught hunting skills by the Tsonga, who were expert in hunting big game, such as Elephants, Rhino, Leopard and Lion. Skukuza, the main camp in the park and which was formerly called Sabi Bridge, was renamed in honour of him. After his death, "the old men of the kraals, some of whom he had sent to prison for poaching, said: 'A great man has gone'".[6] A bronze statue created by the artist Phil Minnaar can be seen in Skukuza depicting Paul Kruger, Piet Grobler and Stevenson-Hamilton, the founding fathers of the park. The Stevenson-Hamilton library is also situated in Skukuza camp.

His legacy also lives on in a books that he authored, namely:

- Notes on a Journey Through Portuguese East Africa: From Ibo To Lake Nyasa (1909)

- Animal Life in Africa (1912) – foreword by Theodore Roosevelt

- The Low-Veld: Its Wildlife and Its People (1929)

- The Kruger National Park (1932)

- South African Eden: From Sabi Game Reserve To Kruger National Park (1937)

- Our South African National Parks (1940)

- Wild Life in South Africa (1947)

- The Barotseland Journal of James Stevenson-Hamilton, 1898-1899 (1953)

Stevenson-Hamilton is commemorated in the scientific name of a species of African gecko, Lygodactylus stevensoni.[14]

References

- Stevenson-Hamilton, James (2008). South African Eden : from Sabi Game Reserve to Kruger National Park. Johannesburg: Penguin. ISBN 9780143185581. OCLC 235940244.

- Carruthers, Jane (2001). Wildlife And Warfare: The Life of James Stevenson-Hamilton. p. 8.

- "Person Page". www.thepeerage.com. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- Hart′s Army list, 1903

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 June 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) (Accessed 8 October 2011)

- Cartwright, A.P. 1960. South Africa's Hall of Fame South Africa: Central News Agency Limited. OCLC: 750076726

- "No. 27359". The London Gazette. 27 September 1901. p. 6304.

- "No. 27494". The London Gazette. 11 November 1902. p. 7167.

- Labuschagne, Rudolph Johannes. 1958. 60 Years, Kruger Park. Pretoria: National Park Board of Trustees of the Union of South Africa.

- Paynter, David, and Nussey, Wilf. 1986. Kruger: Portrait of a National Park. Macmillan South Africa.

- "No. 27487". The London Gazette. 24 October 1902. p. 6736.

- Duggan, A. 1990. Game Parks and Nature Reserves of Southern Africa (2nd edition). Cape Town: The Reader’s Digest Association.

- Carruthers, Jane (2001). Wildlife And Warfare: The Life of James Stevenson-Hamilton. p. 175.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Stevenson", pp. 253-254).

Other sources (to be incorporated)

- Siyabona Africa, 2011, First Warden.(Accessed 8 October 2011)

- The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Bo Beolens, Michael Watkins, Michael Grayson. pp 253–254.