Jan Karski

Jan Karski (24 June 1914[lower-alpha 1] – 13 July 2000) was a Polish soldier, resistance-fighter, and diplomat during World War II. He is known for having acted as a courier in 1940-1943 to the Polish Government-in-Exile and to Poland's Western Allies about the situation in German-occupied Poland. He was reporting about the state of Poland, in which there were many competing factions in the resistance, and also about Germany's destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto and its operation of extermination camps on Polish soil that were murdering Jews, Poles, and others.

Jan Karski | |

|---|---|

Jan Karski photo portrait | |

| Born | Jan Kozielewski 24 April 1914[lower-alpha 1] |

| Died | 13 July 2000 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | Polish, American |

| Other names | Jan Kozielewski (birth name); Piasecki, Kwaśniewski, Znamierowski, Kruszewski, Kucharski, and Witold (akas) |

| Occupation | Polish resistance fighter; diplomat; activist; professor; author |

| Known for | World War II resistance and the Holocaust rescue |

| Spouse(s) | Pola Nireńska |

After emigration to the United States after the war, Karski completed a doctorate and taught for decades at Georgetown University in international relations and Polish history. He lived in Washington, D.C., to the end of his life. He did not speak publicly about his mission during the war until 1981, when he was invited as a speaker to a conference on the liberation of the camps. Karski was featured in Claude Lanzmann's 9-hour Shoah (1985), about the Holocaust and based on numerous oral interviews with Jewish and Polish survivors. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Karski was awarded high honors by the new Polish government, as well as being honored in the US and European nations for his wartime role. In 2010 Lanzmann released a short documentary, The Karski Report, which contained more about Karski's meetings with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other American leaders in 1943.

Karski later stated: "I wanted to save millions, and I was not able to save one man."[1]

Early life

Jan Karski was born Jan Kozielewski on 24 June 1914 in Łódź,[lower-alpha 1] Poland.[6] He was born on St John's Day, and named Jan (the Polish equivalent of John), according to the Polish custom of naming children after the saint(s) of their birthday. An error was made in the baptismal records listing 24 April, as Karski explained later in interviews on several occasions (see Waldemar Piasecki's biography of Karski, One Life, as well as published interviews with his family).[2]

Karski had several brothers and one sister. They were raised as Catholics and he remained so throughout his life. His father died when he was young, and the family struggled financially. Karski grew up in a multi-cultural neighborhood, where the majority of the population at the time was Jewish.

After intensive military training in the prestigious school for mounted artillery officers in Włodzimierz Wołyński, he graduated with a First in the Class of 1936 and ordered to the 5th Regiment of Mounted Artillery. This was the same military unit where Colonel Józef Beck, later Poland's Foreign Affairs Minister, served.

Karski completed his diplomatic education between 1935 and 1938 in various posts in Romania (twice), Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, and went on to join the Diplomatic Service. After completing and gaining a First in Grand Diplomatic Practice, on 1 January 1939 he started work in the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

World War II

During the Polish September Campaign, Kozielewski's 5th Regiment was a unit of the Kraków Cavalry Brigade, under General Zygmunt Piasecki, and a part of Armia Kraków defending the area between Zabkowice and Częstochowa. After the last Battle of Tomaszów Lubelski on 10 September 1939, some units, including 1st Battery of 5th Regiment with Kozielewski, tried to reach Hungary but were captured by the Red Army between 17 and 20 September. Kozielewski was held prisoner in Kozielszczyna camp (presently Ukraine). He successfully concealed his true rank of 2nd Lieutenant and, after a uniform exchange, was identified by the NKVD commander as a Private. He was transferred to the Germans as a person born in Łódź, which was incorporated into the Third Reich, and thus escaped the Katyn massacre of officers by the Soviets.[7]

Resistance

In November 1939 Karski was among POWs on a train bound for a POW camp in General Government (a part of Poland that had not been fully incorporated into The Third Reich). He escaped and made his way to Warsaw. There he joined the SZP (Służba Zwycięstwu Polski) – the first resistance movement in occupied Europe, organized by General Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski, and a predecessor of ZWZ, later the Home Army (AK).

About that time he adopted a nom de guerre of Jan Karski, which he later made his legal name. Other noms de guerre used by him during World War II included Piasecki, Kwaśniewski, Znamierowski, Kruszewski, Kucharski, and Witold. In January 1940 Karski began to organize courier missions to transport dispatches from the Polish underground to the Polish Government in Exile, then based in Paris. As a courier, Karski made several secret trips between France, Britain and Poland. During one such mission in July 1940, he was arrested by the Gestapo in the Tatra Mountains in Slovakia. Severely tortured, he was finally transported to a hospital in Nowy Sącz, from which he was smuggled out with vital help from Józef Cyrankiewicz. After a short period of rehabilitation, he returned to active service in the Information and Propaganda Bureau of the headquarters of the Polish Home Army.

In 1942 Karski was selected by Cyryl Ratajski, the Polish Government Delegate's Office at Home, to perform a secret mission to prime minister Władysław Sikorski in London. Karski was to contact Sikorski, as well as various other Polish politicians, and inform them about Nazi atrocities in occupied Poland. In order to gather evidence, Karski met Bund activist Leon Feiner; he was twice smuggled by Jewish underground leaders into the Warsaw Ghetto in order to directly observe what was happening to Polish Jews.[8]

My job was just to walk. And observe. And remember. The odour. The children. Dirty. Lying. I saw a man standing with blank eyes. I asked the guide: what is he doing? The guide whispered: “He’s just dying”. I remember degradation, starvation and dead bodies lying on the street. We were walking the streets and my guide kept repeating: “Look at it, remember, remember” And I did remember. The dirty streets. The stench. Everywhere. Suffocating. Nervousness.[8]

Disguised as an Estonian camp guard,[8] he visited what he thought was Bełżec death camp. It appears that Karski in fact witnessed a Durchgangslager (transit camp) for Bełżec in the town of Izbica Lubelska, located midway between Lublin and Bełżec.[9] Many historians have accepted this interpretation, as did Karski himself.[10]

Reporting Nazi atrocities to the Western Allies

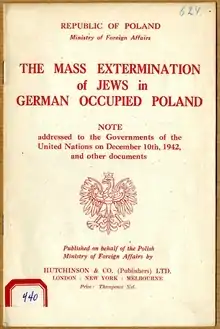

Starting in 1940,[11] Karski reported to the Polish, British, and U.S. governments on the situation in Poland, especially on the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto and the Nazi extermination of Polish Jews. He had also carried out of Poland a microfilm with further information from the underground movement on the extermination of European Jews in German-occupied Poland. His reports were transcribed and translated by Walentyna Stocker, the personal secretary and interpreter for Sikorski.[12] Based on the microfilm transported by Karski, Polish Foreign Minister Count Edward Raczyński provided the Allies with one of the earliest and most accurate accounts of the Nazi Holocaust. A note by Raczynski, entitled The mass extermination of Jews in German occupied Poland, addressed to the governments of the United Nations on 10 December 1942, was later published along with other documents in a widely distributed leaflet.[13]

Karski met with Polish politicians in exile including the Prime Minister, as well as members of political parties such as the Socialist Party, National Party, Labor Party, People's Party, Jewish Bund and Poalei Zion. He also spoke to the British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, giving a detailed account of what he had seen in Warsaw and Bełżec. In 1943 in London he met Hungarian-British writer Arthur Koestler, who had written Darkness at Noon (1940).

Karski also traveled to the United States, where on 28 July 1943 he personally met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the Oval Office, the first eyewitness to tell him about the situation in Poland and the Jewish Holocaust.[14] However, Roosevelt did not ask one question about the Jews.[15] Karski met with many other government and civic leaders in the United States, including Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, Cordell Hull, William Joseph Donovan, and Rabbi Stephen Wise. Karski presented his report to media, bishops of various denominations (including Cardinal Samuel Stritch), members of the Hollywood film industry and artists, but without much result, as most people could not comprehend the scale of extermination that he recounted.[16][17][14] But his accounts about the problems of stateless people and their vulnerability to murder helped inspire the formation of the War Refugee Board during the war,[18] changing US government policy from neutral towards supportive for the plight of war refugees and civilians in Europe,[19] and after the war, also inspiring the creation of the Office of High Commissioner for Refugees after the war.

In 1944, Karski published Courier from Poland: The Story of a Secret State (a selection was featured in Collier's magazine six weeks before the book's publication).[20][21] He related his experiences in wartime Poland. The book sold more than 400,000 copies through the end of World War II. A film adaptation was planned but never realized.[22]

According to historian Adam Puławski, Karski's main mission as a courier was to alert the Government in Exile to conflicts within the underground movements in Poland. He discussed the Warsaw Ghetto liquidation as part of that account, almost incidentally.[23] Without diminishing Karski's contributions, Puławski notes that facts about the Holocaust were available to the Allies for at least a year and half before Karski met with Roosevelt, and that to say that his mission was primarily reporting on the Holocaust is in error.[23] According to a contemporary note, when Karski met with Anthony Eden, the latter pressed for more information on the fate of Polish Jews while Karski wanted to discuss Soviet designs for Poland.[24]

Life in the United States

After the war ended, Karski remained in the United States in Washington, D.C. He began graduate studies at Georgetown University, receiving a PhD from the institution in 1952.[25] In 1954, Karski became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

He taught at Georgetown University for 40 years in the areas of East European affairs, comparative government and international affairs. Among his students was Bill Clinton (Class of 1968). In 1985, he published the academic study The Great Powers and Poland, based on research during a Fulbright fellowship in 1974 to his native Poland.

Karski's 1942 report on the Holocaust and the London Polish government's appeal to the United Nations were briefly recounted by Walter Laqueur in his history The Terrible Secret: Suppression of the Truth about Hitler's Final Solution (1980).

Karski did not speak publicly about his wartime mission until 1981, when he was invited by activist Elie Wiesel as a keynote speaker at the International Liberators Conference in Washington, D.C.[26]

French film-maker Claude Lanzmann had interviewed him at length in 1978, as part of his preparation for his documentary Shoah,, but it was not released until 1985. Lanzmann had asked participants not to make other public statements during that time, but Karski got a release for the conference.[26] The 9-hour film included a total of 40 minutes of testimony by Karski.[8] This section was from the first of two days when Lanzmann had interviewed Karski. It ends with Karski saying that he made his report to leaders.

Lanzman later said that, on the second day of interviews, Karski recounted in precise detail his meetings with Roosevelt and other high American officials. Lanzman said that the tone and style of Karski's second interview was so different, and the interview so long, that it did not fit his vision for the film and he did not use it.[27]

Unhappy with how he was presented in the film, Karski published an article, book, Shoah, a Biased Vision of the Holocaust (1987), in the French journal Kultura. He argued for another documentary to include his missing testimony and also to show more of the help given to Jews by many Poles (some are now recognized by Israel as the Polish Righteous among the Nations). (The book was published in English, French and Polish.)[28][29]

Following the fall of communism in Poland in 1989, Karski's wartime role was officially acknowledged by the new government. He was awarded the Order of the White Eagle (the highest Polish civil decoration) and the Order Virtuti Militari (the highest military decoration awarded for bravery in combat).

In 1994, E. Thomas Wood and Stanisław M. Jankowski published a biography, Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust. They noted that Karski had urged production of another documentary to correct what he thought was the bias in Lanzmann's Shoah.

During an interview with Hannah Rosen in 1995, Karski discussed the Allies' failure to rescue most of the Jews from mass murder:

It was easy for the Nazis to kill Jews, because they did it. The Allies considered it impossible and too costly to rescue the Jews, because they didn't do it. The Jews were abandoned by all governments, church hierarchies and societies, but thousands of Jews survived because thousands of individuals in Poland, France, Belgium, Denmark, Holland helped to save Jews. Now, every government and church says, "We tried to help the Jews", because they are ashamed, they want to keep their reputations. They didn't help, because six million Jews perished, but those in the government, in the churches they survived. No one did enough.[30]

The documentary film My Mission (1997), directed by Waldemar Piasecki and Michal Fajbusiewicz, presented the full details of Karski's war mission. In 1999, Piasecki published Tajne Panstwo ("Secret State", edited and adapted from Karski's wartime book), which became a bestseller. In the same year, the Museum of the City of Łódź opened "Jan Karski's Room", devoted to the most valuable memorabilia, documents and decorations, and organized under Karski's supervision.

After Karski's death

In 2010, French author Yannick Haenel published a novel Jan Karski, drawn from the courier's World War II activities and memoir. Haenel also added a third part in which he inserted his own views into Karski's "character", particularly in his approach to Karski's meeting with President Roosevelt and other American leaders. Claude Lanzmann criticized the author strongly and argued that Haenel ignored important historic elements of the time. Haenel said that was part of his freedom in fiction.[26]

In response, Lanzmann released the second half of his interview with Karski as a 49-minute documentary in 2010, edited and entitled The Karski Report, also on ARTE.[27][31] It is mostly about Karski's meeting with President Roosevelt and other American leaders. Karski had met with Chief Justice Felix Frankfurter, who said: "I did not say that he was lying, I said that I could not believe him. There is a difference." As The Guardian said, "Human inability to believe in the intolerable is what The Karski Report is about. At the start of the film, Lanzmann quotes the French philosopher Raymond Aron, who, when asked about the Holocaust, said: "I knew, but I didn't believe it, and because I didn't believe it, I didn't know."[31]

Karski's wartime book was re-published posthumously by Georgetown University Press as My Report to the World: The Story of a Secret State (2013).[32] A Tribute to Jan Karski panel discussion was held at the University that year in conjunction with the book release. It featured a discussion of Karski's legacy by School of Foreign Service Dean Carol Lancaster, Georgetown University Chair of the board of directors Paul Tagliabue, former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, former National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, Polish Ambassador Ryszard Schnepf, and Rabbi Harold S. White.[33]

Personal life

Karski had several siblings, mostly brothers: Marian, Boguslaw, Cyjrian, Edmund, Stefan, and Uzef and a sister Laura.

Karski's eldest brother, Marian Kozielewski (b. 1898), reached the rank of colonel in the military and was also considered a hero in World War II. He had been arrested by the Germans in Warsaw in 1940 and was among Catholic Poles who survived being imprisoned as political prisoners at Auschwitz concentration camp. After being released in 1941, he returned to Warsaw and joined the resistance. The Kozielewski brothers admired Jozef Pilsudski and members of the "forgotten army", who had suffered many deeply personal wounds. After the war Marian emigrated initially to Canada, where he married. He struggled as a refugee, holding low-level jobs after settling in Washington, D.C., in 1960 near his brother Jan. Marian Kozielewski committed suicide there in 1964 and is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery.

In 1965, Karski married Pola Nireńska, a 54-year-old Polish Jew who was a dancer and choreographer. (With the exception of her parents, who had emigrated to Israel in 1939 shortly before the Nazi invasion of Poland, all of her family died in the Holocaust.) She committed suicide in 1992.

Karski died of unspecified heart and kidney disease in Washington, D.C., in 2000. He died at Georgetown University Hospital.[34] He was interred at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, next to the graves of his wife, Pola Nirenska, and brother Marian. He and Pola had no children.

Honors/legacy

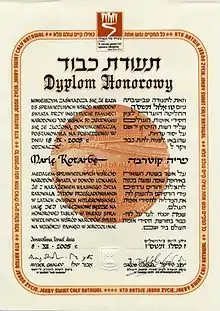

On 2 June 1982, Yad Vashem recognised Jan Karski as Righteous Among the Nations.[35] A tree bearing a memorial plaque in his name was planted that same year at Yad Vashem's Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations in Jerusalem.

In 1991, Karski was awarded the Wallenberg Medal of the University of Michigan. Statues honoring Karski have been placed in New York City at the corner of 37th Street and Madison Avenue (renamed as Jan Karski Corner)[36] and on the grounds of Georgetown University[37] in Washington, D.C.[38] Additional benches, which were made by the Kraków-based sculptor Karol Badyna, are located in Kielce, Łódź and Warsaw in Poland, and on campus of the Tel Aviv University in Israel. The talking Karski bench in Warsaw near the Museum of the History of Polish Jews has a button to activate a short talk by Karski about the war. Georgetown University, Oregon State University, Baltimore Hebrew College, Warsaw University, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, and the University of Łódź all awarded Karski honorary doctorates.

In 1994, Karski was made an honorary citizen of Israel in honor of his efforts on behalf of Polish Jews during the Holocaust. Karski was nominated for the Nobel Prize and formally recognized by the UN General Assembly shortly before his death.

Shortly after his death, the Jan Karski Society was established, initiated by his close friend, collaborator and biographer, Professor Waldemar Piasecki. The society preserves his legacy and administers the Jan Karski Eagle Award, which he had established in 2000. The list of laureates includes: Elie Wiesel, Shimon Peres, Lech Walesa, Aleksander Kwasniewski, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Bronislaw Geremek, Jacek Kuron, Adam Michnik, Karol Modzelewski, Oriana Fallaci, Dagoberto Valdés Hernández, Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, Tygodnik Powszechny magazine, the Hoover Institution, and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

In April 2011, the Jan Karski U.S. Centennial Campaign was created to increase interest in the life and legacy of the late Polish diplomat, as the Centennial year of his birth in 2014 approached. The U.S. Campaign, headed by Polish-American author Wanda Urbanska, worked in partnership with the International Legacy program at the Polish History Museum in Warsaw, under the direction of Ewa Wierzynska. Polish Consul General Ewa Junczyk-Ziomecka hosted a gala kickoff dinner in New York City on 30 May, consisting of representatives from Georgetown University, and the Polish Catholic and Jewish groups who comprised the steering committee.

The campaign group was seeking to obtain the Presidential Medal of Freedom for Karski in advance of his Centennial. In addition, they wanted to promote educational activities, including workshops, artistic performances and reprint his 1944 book, Story of a Secret State. In December 2011, the support of 68 U.S. Representatives and 12 U.S. Senators was obtained and a supporting nomination for the Medal was submitted to the White House.[39] On 23 April 2012, U.S. President Barack Obama announced that Karski would receive the country's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[40] The Medal was awarded posthumously by President Obama on 29 May 2012 and presented to Adam Daniel Rotfeld, the former Foreign Minister of Poland and himself a Jewish Holocaust survivor.[41] Jan Karski's family was not invited for the presentation ceremony, which they strongly protested. The medal, along with other honors given to Karski, is on display at "the Karski office" in Łódź Museum. This is in accordance with the wishes of his surviving family, led by his niece and goddaughter Dr. Kozielewska-Trzaska.

A controversy began when a misspoken word in Barack Obama's Presidential Medal of Freedom speech came to be known as "Gafa Obamy" or Obama's gaffe,[42] when the President referred to "a Polish death camp" (instead of "death camp in Poland") when talking of the Nazi German transit death camp that Karski had visited. "Polish death camps" is a term often used to refer to Nazi concentration camps in Poland, as opposed to (as may be implied) Polish concentration camps. The terms "Polish death camp" or "Polish concentration camp" were reportedly promulgated by ex-Nazis working for the West German secret services. Historian Leszek Pietrzak explains the propaganda strategies from the 1950s.[43] President Obama later characterized his term as a mis-statement and it was accepted by Polish President Bronisław Komorowski.[44]

In November 2012, having met its major goals, the Jan Karski U.S. Centennial Campaign was succeeded by the Jan Karski Educational Foundation, which continues to promote Karski's legacy and values, particularly to young people from middle school through college age. The President of the Foundation is Polish-American author Wanda Urbanska.[45] The Foundation sponsored three major conferences about Karski in his centennial birth year, at Georgetown University in Washington, at Loyola University in Chicago, and in Warsaw.

In early February 2014, Jan Karski Society and the Karski family appealed to President of Poland Bronisław Komorowski to posthumously promote Jan Karski to the rank of Brigadier General in recognition of his contribution to the war effort as well as all couriers and emissaries of Underground Polish State. The appeal received no response for a year. Member of the Polish parliament Professor Tadeusz Iwinski recently openly criticized the president of Poland for inaction on Karski's behalf.

On 24 June 2014, the "Jan Karski. Mission Accomplished" Conference took place in Lublin under the patronage of Professor Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, Aleksander Kwasniewski, President of Poland (1995–2005), Moshe Kantor, President of the European Jewish Congress, and Michael Schudrich, Chief Rabbi of Poland.

Remembering Karski's mission

The former Foreign Minister of Poland Władysław Bartoszewski in his speech at the ceremony of the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 27 January 2005, said: "The Polish resistance movement kept informing and alerting the free world to the situation. In the last quarter of 1942, thanks to the Polish emissary Jan Karski and his mission, and also by other means, the Governments of the United Kingdom and of the United States were well informed about what was going on in Auschwitz-Birkenau."[46]

A full-length play on Karski's life and mission, Coming to See Aunt Sophie (2014), written by Arthur Feinsod, was produced in Germany and Poland. An English translation was produced in Bloomington, Indiana at the Jewish Theatre in June 2015, and in Australia in August of that year.

A new play, My Report to the World, written by Clark Young and Derek Goldman, premiered at Georgetown University during the conference honoring Karski's centennial year. It starred Oscar-nominated actor David Strathairn as Karski. It was performed in Warsaw before being produced in New York in July 2015; Strathairn played in the Karski role in all productions. Goldman directed the play in both Washington, D.C., and New York. The July performances were presented in partnership with The Museum of Jewish Heritage, The Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics at Georgetown University, Bisno Productions, and the Jan Karski Educational Foundation.

Awards and decorations

- Order of the White Eagle

- Silver Cross of the Virtuti Militari, twice

- Home Army Cross

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (United States)

See also

- Bermuda Conference

- Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

- Polish Secret State

- Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust

- Victor Martin – a Belgian academic, sent by the Belgian resistance to report on the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp

- Witold Pilecki

- Irena Sendler

- Szmul Zygielbojm

References

Notes

- Karski's date of birth is sometimes given as 24 April 1914, based on his baptismal records in Russian and subsequently shown on his official birth certificate. 24 June was confirmed by the Karski's family lawyer, Dr. Wieslawa Kozielewska-Trzaska, by Karski's niece and god-daughter, and by the Jan Karski Society, an organization established shortly after his death to preserve his legacy. It is the date Karski himself used on handwritten documents, including several diplomatic dossiers at the League of Nations.[2]

24 April was the birth date shown on both the diploma for Karski's master's degree (awarded in 1935) and his certificate from the Artillery Reserve Officer Cadet School (awarded in 1936).[3] Some Karski tribute organizations also recognize 24 April as his birth date, as does the Google Cultural Institute's documentation, Museum of Polish History, and the Museum of the City of Łódź, to which Karski left his papers, awards and artwork. The Polish PWN Encyclopedia recognizes 24 April as his birth date.[4]

In March 2014, the United States Senate adopted a resolution honoring Karski on the centennial of his birth, 24 April 2014. The resolution was withdrawn and revised to recognize Karski on 24 June 2014, according to the Polish Press Agency.[5] The Polish Senate did the same, according to the office of Bogdan Borusewicz.

Karski's diplomatic passport showed his date of birth as 22 March 1912.

Footnotes

- "20. rocznica śmierci Jana Karskiego. "Ludzie nie mogą zapomnieć, co to jest Holokaust"". PolskieRadio.pl. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Patryk Małecki (27 November 2013). "Jan Karski was born 24 June 1914. Nothing is going to change that" [Jan Karski urodził się 24 czerwca 1914 roku. Nic tego nie zmieni]. Washington, D.C.: Dziennikwschodni.pl. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013 – via Internet Archive.

- Jan Karski. Fotobiografia, by Maciej Sadowski, Warsaw: Veda, 2014, www.veda.com.pl

- "Encyklopedia PWN – Sprawdzić możesz wszędzie, zweryfikuj wiedzę w serwisie PWN – Karski Jan". Encyklopedia.pwn.pl. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Polish Press Agency. "World News. Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 April 2014 – via Internet Archive, 2014-04-28.

- Patryk Małecki (27 November 2013). "Jan Karski was born 24 June 1914. Nothing is going to change that" [Jan Karski urodził się 24 czerwca 1914 roku. Nic tego nie zmieni]. Washington, D.C.: Dziennikwschodni.pl. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013 – via Internet Archive.

- Deroy Murdock (May 28, 2012), "WWII Hero Wins Presidential Medal of Freedom. Jan Karski was the first to warn FDR about the Final Solution.", National Review Online. Internet Archive.

- Zgierski, Jakub (24 January 2019). "Jan Karski. Witness to the Holocaust". Europeana (CC By-SA). Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Jakob Weiss, The Lemberg Mosaic (New York: Alderbrook Press 2011) fn 199, p.409

- In his book published in the USA during the war, Karski identified the camp as Bełżec death camp, although he knew at the time that the camp could not have been in Bełżec. The descriptions he gave are incongruous with what is now known about Bełżec. His biographers Wood and Jankowski later suggested that Karski had been observing the Izbica Lubelska "sorting camp". This theory was first time presented by Prof. Jozef Marszalek from Maria Curie-Sklodowska University of Lublin (UMCS), WW II historian and top specialist on Nazi camps in occupied Poland. Many historians have accepted this theory, as did Karski.

- Engel, David (1983). "An Early Account of Polish Jewry under Nazi and Soviet Occupation Presented to the Polish Government-In-Exile, February 1940". Jewish Social Studies. 45 (1): 1–16. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4467201.

- Roberts, Sam (20 April 2020). "Walentyna Janta-Polczynska, Polish War Heroine, Dies at 107". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Mass extermination". Projectinposterum.org. 10 December 1942. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- Jan Karski (5 May 2011). Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World: My Report to the World. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 407–. ISBN 978-0-14-196844-5.

- Gerd Bayer; Oleksandr Kobrynskyy (1 December 2015). Holocaust Cinema in the Twenty-First Century: Images, Memory, and the Ethics of Representation. Columbia University Press. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-0-231-85091-9.

- Richard L. Rashke (1995). Escape from Sobibor. University of Illinois Press. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-0-252-06479-1.

- Robert L. Beir (1 June 2013). Roosevelt and the Holocaust: How FDR Saved the Jews and Brought Hope to a Nation. Skyhorse. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-62636-366-3.

- Richard J. Golsan (20 December 2016). The Vichy Past in France Today: Corruptions of Memory. Lexington Books. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-1-4985-5033-8.

- Robert L. Beir (1 June 2013). Roosevelt and the Holocaust: How FDR Saved the Jews and Brought Hope to a Nation. Skyhorse. pp. 276–. ISBN 978-1-62636-366-3.

- Karski, Jan. (1944). "Polish Death Camp," Collier's, 14 October, pp. 18–19, 60–61.

- Abzug, Robert. H. (1999). America Views the Holocaust, 1933–1945: A Brief Documentary History. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, p. 183.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- From an April 5, 2015 interview with Waldemar Kowalski of the Polish Press Agency, as quoted in Grudzinska-Gross, Irena (2016). "Polishness in Practice". In Irena Grudzinska-Gross; Iwa Nawrocki (eds.). Poland and Polin: New Interpretations in Polish-Jewish Studies. Frankfurt a.M: Peter Lang. p. 37. ISBN 978-3-653-96123-2. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Gmiterek-Zabłocka, Anna (5 July 2019). "Historyk obala mity na temat Jana Karskiego. Po latach badań stwierdza: Był bohaterem, ale w innym sensie". TOK FM (in Polish). Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- Karski, J. Material Towards A Documentary History of the Fall of Eastern Europe (1938–1948); Ph.D. dissertation 1952 for Georgetown University; publication number AAT 0183534

- Besson, Rémy (May 2011). "Le Rapport Karski. Une voix qui résonne comme une source (The Karski Report. A Voice with the Ring of Truth, translated by John Tittensour)". Études photographiques (27). Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Shoah : a biased account of the Holocaust. - University of Toronto Libraries. search.library.utoronto.ca. Polish American Congress. 1987. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Revue ESPRIT". Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "Interview with Jan Karski". Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- Jeffries, Stuart (9 June 2011). "Claude Lanzmann on why Holocaust documentary Shoah still matters". The Guardian. London.

- Storozynski, Alex (28 March 2014). "Karski's Story of a Secret State – A Primer on the Polish Ethos". huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- "Georgetown University video of the event". Georgetown.edu. 18 March 2013. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- Kaufman, Michael T. "Jan Karski Dies at 86; Warned West About Holocaust." New York Times. 15 July 2000.

- "Yad Vashem recognizes Karski". yadvashem.org. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- "Statue salutes Polish man who warned FDR of Nazi camps", New York Daily News, 12 November 2007

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Monument to Honor Dr. Jan Karski", Polish-American Journal. 30 September 2002. vol 91; No. 9; page 8

- Jan Karski. "Jan Karski Educational Foundation (home)". Jankarski.net. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- "President Obama Announces Jan Karski as a Recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom". whitehouse.gov. 26 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "2012 Presidential Medal of Freedom Ceremony". Whitehouse.gov. 29 May 2012. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- "Matthew Kaminski: 'Gafa Obamy'". The Wall Street Journal. 30 May 2012.

- "Jak Niemcy Polaków wrabiali w mordowanie Żydów – Leszek Pietrzak – NowyEkran.pl". Archived from the original on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- "President of the Republic of Poland / News / News / President on Barack Obama's letter". President.pl. 1 June 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- Jan Karski. "www.jankarski.net". Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- Address by the former Foreign Minister of Poland Wladysław Bartoszewski at the ceremony of the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 27 January 2005 see pp. 156–157

Bibliography

- Publications by Karski

- "Polish Death Camp." Collier's, 14 October 1944, pp. 18–19, 60–61.

- Courier from Poland: The Story of a Secret State, Boston 1944 (Polish edition: Tajne państwo: opowieść o polskim Podziemiu, Warszawa 1999).

- Wielkie mocarstwa wobec Polski: 1919–1945 od Wersalu do Jałty. wyd. I krajowe Warszawa 1992, Wyd. PIW ISBN 83-06-02162-2

- Tajna dyplomacja Churchilla i Roosevelta w sprawie Polski: 1940–1945.

- Polska powinna stać się pomostem między narodami Europy Zachodniej i jej wschodnimi sąsiadami, Łódź 1997.

- Jan Karski (2001). Story of a Secret State. Simon Publications. p. 391. ISBN 1-931541-39-6.

- About Karski

- E. Thomas Wood & Stanisław M. Jankowski (1994). Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust. John Wiley & Sons Inc. page 316; ISBN 0-471-01856-2

- J. Korczak, Misja ostatniej nadziei, Warszawa 1992.

- E. T. Wood, Karski: opowieść o emisariuszu, Kraków 1996.

- J. Korczak, Karski, Warszawa 2001.

- S. M. Jankowski, Karski: raporty tajnego emisariusza, Poznań 2009.

- Henry R. Lew, Lion Hearts Hybrid Publishers, Melbourne, Australia 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jan Karski. |

- Works by or about Jan Karski at Internet Archive

- Jan Karski – his activity to save Jews' lives during the Holocaust, at Yad Vashem website

- The Jan Karski papers at the Hoover Institution Archives

- Interviews with Jan Karski

- U.S Holocaust memorial Museum, Claude Lanzmann Interview with Jan Karski

- Photographic Memory: Snapshots of a Spy, Culture.pl

- Jan Karski and Culture.pl