Jane Colden

Jane Colden (March 27, 1724 – March 10, 1766) was an American botanist,[2]:53–4 described as the "first botanist of her sex in her country" by Asa Gray in 1843.[3] Although not acknowledged in contemporary botanical publications, she wrote a number of letters resulting in botanist John Ellis writing to Carl Linnaeus of her work applying the Linnaean system of plant identification to American flora, for which botanist Peter Collinson stated "she deserves to be celebrated".[2]:54[1] Contemporary scholarship maintains that she was the first female botanist working in America. She was regarded as a respected botanist by many prominent botanists including John Bartram, Peter Collinson, Alexander Garden, and Carl Linnaeus. Colden is most famous for her untitled manuscript, housed in the British Museum, in which she describes the flora of the Hudson Valley in the Newburgh region of New York state, including ink drawings of 340 different species.[1]

Jane Colden | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 27, 1724 New York City, New York |

| Died | March 10, 1766 (aged 41) |

| Occupation | Botanist |

| Known for | First American female botanist"[1] |

| Spouse(s) | William Farquhar |

| Parent(s) |

|

Early life

Colden was born in New York City, the fifth child of Cadwallader Colden, who was a physician who trained at the University of Edinburgh and became involved in the politics and management of New York after arriving in the city from Scotland in 1718, and Alice Christy Colden, the daughter of a clergyman and had been brought up in Scotland in an intellectual atmosphere. Mrs. Colden is often referred to as "the capable instructress of her children."[1] She was educated at home and her father provided her with botanical training following the new classification system developed by Carl Linnaeus.[4] The family's move to a 3,000-acre estate (1,200 ha) in Orange County stimulated the botanical interests of both Cadwallader and Jane Colden.[5] Cadwalleder Colden had been the first to apply the system of botanical classification developed by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (Linnaean Taxonomy) to an American plant collection and he translated the text of Linnaeus’ books into English.[6]

Due to the lack of schools and gardens around the area, her father wrote to Peter Collinson, where he inquired about getting sent "the best cuts or pictures of [plants] for which purpose I would buy for her Tourneforts Institutes and Morison’s Historia plantarum, or if you know any better books for this purpose as you are a better judge than I am I will be obliged to you in making the choice"[7] in order for Jane to continue her studies of botanical sciences. Besides obtaining libraries and samples for his daughter, Cadwallader also surrounded her with like-minded scientists, including Peter Kalm and William Bartram. In 1754, a notable gathering with Alexander Garden and William Bartram sparked Jane's interests even more and allowed the fruition of the collaboration and friendship between Jane and Garden to flourish.[7] Garden, an active collector of his local flora, later corresponded with Jane, exchanged seeds and plants with her, and instructed her in the preservation of butterflies. Of his daughter, Cadwallader wrote in a 1755 letter to Dr. John Frederic Gronovius, a colleague of Linneaus, that she possessed "a natural inclination to reading and a natural curiosity for natural philosophy and natural history." He wrote that Jane was already writing descriptions of plants using Linnaeus' classification and taking impressions of leaves using a press. In this letter, Cadwallader sought to earn her a position with Dr. Gronovius sending seeds or samples.[8]

Career

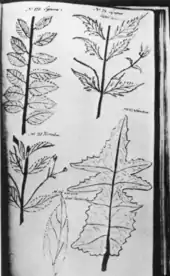

Between 1753 and 1758 Colden catalogued New York's flora, compiling specimens and information on more than 400[5] species of plants from the lower Hudson River Valley, and classifying them according to the system developed by Linnaeus. She developed a technique for making ink impressions of leaves, and was also a skilled illustrator, doing ink drawings of 340. For many drawings she wrote additional botanical details as well as culinary, folklore or medicinal uses for the plant, including information from indigenous people.[9] On January 20, 1756, Peter Collinson wrote to John Bartram that "Our friend Colden's daughter has, in a scientific manner, sent over several sheets of plants, very curiously anatomized after this [Linnaeus's] method. I believe she is the first lady that has attempted anything of this nature." In this instance Colden was recognized as what she is known today by the Dictionary of American Biography, the first female botanist in America.[5] Colden participated in the Natural History Circle where she exchanged seeds and plants with other plant collectors in the American colonies and in Europe.[10] These rounds with the Natural History Circle encouraged Jane to become a botanist. Through her father, she met and corresponded with many leading naturalists of the time, including Carolus Linnaeus. One of her descriptions of a new plant, which she herself called Fibraurea, was forwarded to Linnaeus with the suggestion that he should call it Coldenella, but Linnaeus refused and called it Helleborus (now Coptis groenlandica).[9]

In 1756 Colden discovered the plant which is now known as Triadenum virginicum and proposed a name after the prominent botanist Garden. In her manuscript she wrote that this plant was without an Order under the Linnaean system.[1] In her description Colden wrote, " The three chives only in each bundle, and the three oval-shap'd bodies on the seat of the flower, together with the seat to which the seeds adhere, distinguish this plant from the hypericums; and I think, not only make it a different genus, but likewise makes an order which Linnaeus has not. "[1] However, the name was not allowed because an English botanist named John Ellis had already named the Cape jasmine as Gardenia jasminoides, and was entitled to its use because of the conventions of botanical nomenclature.[11]

In spite of all of Colden's accomplishments, she has never been formally honored by having a taxon named after her. The genus Coldenia is named after her father.[5]

Colden's manuscript

Colden's manuscript, in which she had ink drawing of leaves and description of the plants, was never named. Colden's original manuscript describing the flora of New York has been held in the British Museum since the mid-1800s after passing through the hands of several collectors.[5] Ricketts and Hall (1963) published transcripts of 57 of Colden's plant descriptions with the drawings and index of the original manuscript. They also analyzed and evaluated Colden's work. Her manuscript drawing consisted only of leaves and these drawings were only ink outlines colored in with neutral tint. However, their analysis did say that her descriptions were "excellent-full , careful, and evidently taken from living specimens."[1] Colden's descriptions include morphological details of flower, fruit, and plant structure, as well as ways on how to use certain plants for medicinal or culinary purposes. Some of the descriptions include the month of flowering and the habitat they are found in. Records were written in a legible, consistent hand writing with neatly underlined headings and subheadings. Latin and common names for the plants are given.[7]

Some species she went on to illustrate, press and describe included: Phytolacca decandra (now P. americana), Polygala senega, Erythronium americanum, Ambrosia artemisifolia, Monarda didyma, and Clematis virginiana. In her section "Observat" (now known as observations) she pointing out to Linnaeus that "there are some plants of Clematis that bear only male flowers, this I have observed with such care that there can be no doubt about it".[7] This shows the long hours she spent doing observations, which were consistent, accurate and replicable. Jane Colden documented her findings of an entirely new flora for her countrymen and for eager Europeans, and it is with this in mind that we can fully understand her delight in botany and appreciate her contribution.[7]

Colden's manuscript has a title page added in 1801 by Ernst Gottfried Baldinger, who was a professor at the universities of Jena and Marburg. He wrote in Latin "Flora Nov.- Eboracensis," translated as "Flora of New York," in English.

Her manuscript can be purchased on amazon or can be borrowed from many libraries across North America, Europe and the UK.

Personal life

Visitors to her family home noted that she made excellent cheese and she recorded them in the document Memorandum of Cheese made in 1756.[1]

Colden married Scottish widower Dr. William Farquhar on March 12, 1759.[8] She died seven years later at the age of 41; in the same year her only child died.[8] There is no evidence that she continued her botanical work after her marriage.[1]

Legacy

Americans did not become aware of Colden's manuscript until 75 years later when Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps stated that another female botanist before her was the first American lady to illustrate the science of botany.[1]

The Jane Colden Memorial Garden was constructed in 1957 in her home town by the Garden Clubs of Orange and Dutchess Counties containing species that she had described.[12] This was at what is now Knox's Headquarters State Historic Site in New Windsor, near where she lived and worked.[13] It was maintained by volunteers and, despite individual efforts, reached a poor state of maintenance in the 1990s. In 2014 a project was started to restore the garden.

See also

References

Citations

- Smith, Beatrice (July 1988). "Jane Colden and Her Botanic Manuscript". American Journal of Botany. 75 (7): 1090–1096. doi:10.2307/2443778. JSTOR 2443778.

- Makers of American Botany, Harry Baker Humphrey, Ronald Press Company, Library of Congress Card Number 61-18435

- Cadwallader Colden; Peter Collinson; Asa Gray; Johannes Fredericus Gronovius; Carl von Linné (1843). Selections from the scientific correspondence of Cadwallader Colden with Gronovius, Linnaeus, Collinson, and other naturalists. p. 22. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- Gronim, Sara Stidstone (2007). "What Jane Knew: A Woman Botanist in the Eighteenth Century". Journal of Women's History. 19 (3): 33–59. doi:10.1353/jowh.2007.0058.

- Imbler, Sabrina (2019-09-20). "Centuries Later, America's First Female Botanist Lives On in a Community Garden". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- “Jane Colden.” Journal of the Sierra College Natural History Museum, vol. 6, no. 1, 2015, https://www.sierracollege.edu/ejournals/jscnhm/v6n1/colden.html.

- Harrison, Mary. “Jane Colden: Colonial American Botanist.” Arnoldia Magazine, 1995, pp. 19–26.

- Vail, Anna Murray (1 January 1907). "JANE COLDEN, AN EARLY NEW YORK BOTANIST". Torreya. 7 (2): 21–34. JSTOR 40594571.

- Bonta, Marcia Myers (1991). Women in the field : America's pioneering women naturalists (1st ed.). College Station: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-489-7.

- Sterling, Keir Brooks (1997). Biographical Dictionary of American and Canadian Naturalists and Environmentalists. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-0-313-23047-9.

- https://www.nybg.org/blogs/science-talk/2014/03/americas-first-female-botanist/

- Imbler, Sabrina (20 September 2019). "Centuries Later, America's First Female Botanist Lives On in a Community Garden". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- "Knox's Headquarters State Historic Site, NY". The Palisades Historic Sites Conservancy. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- IPNI. Colden.

Sources

- Bonta, Marcia Myers. 1991 — Women in the Field: America's pioneering women nauturalists — College Station: Texas A & M University Press.

- Harrison, Mary. “Jane Colden: Colonial American Botanist.” Arnoldia, vol. 55, no. 2, 1995, pp. 19–26.

- Shapiro, B. 2000. Colden, Jane. American National Biography Online

- Smith, B . S. 1988. Jane Colden (1724–1766) and her manuscript. American Journal of Botany 75:1090–1096

- Botanic Manuscript of Jane Colden – First Woman Botanist of Colonial America, Published by the Garden Club of Orange and Dutchess Counties, New York. Produced by Chanticleer Press, New York. April 1963. Includes reproduction of Manuscript in the British Museum.