Japanese values

Japanese values are cultural goals, beliefs and behaviors that are considered important in Japanese culture.

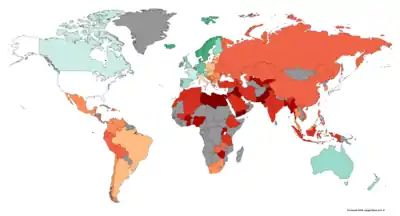

Global perspective

|

+1.5 to +0.2

+0.1 to +1.5

+0.5 to +0.1

0 to +0.5

0 |

0 to −0.05

−0.05 to −0.1

−0.1 to −0.15

−0.15 to −0.2

−0.2 to −0.25 |

−0.25 to −0.3

−0.3 to −0.35

No available data |

In global perspective, Japanese culture scores higher on emancipative values (individual freedom and equality between individuals) and individualism than most other cultures, including those from the Middle East and Northern Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, India and other South Asian countries, Central Asia, South-East Asia, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Central America and South America.

Cultures from Western Europe score higher than Japanese culture in emancipative values and individualism.[1][2][3][4] There is a similar level of emancipative values and individualism in the cultures of United States and Japan.[5]

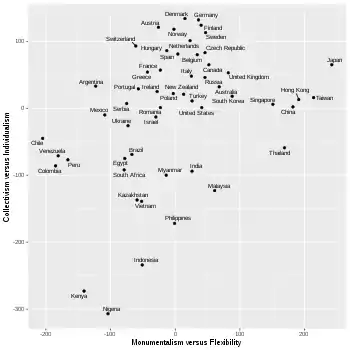

According to the theory of flexibility cultures and monumentalist cultures elaborated by social anthropologist Michael Minkov, certain societies emphasize adaptation to change and self-improvement (flexibility cultures) while others prioritize tradition and self-stability (monumentalist cultures). Japanese culture emphasizes flexibility more than most other cultures. Among a sample of 54 national cultures selected from all major regions of the world, Japanese culture ranked first on the flexibility index. The flexibility orientation of cultures is strongly correlated with educational achievement of students on international tests such as PISA and TIMSS.[6]

History of scholarship

The writings of late 19th through early 20th century Western travellers such as Basil Hall Chamberlain, George Trumbull Ladd and Percival Lowell influenced later ideas about Japanese values in both popular and academic discourse.[7]

Ruth Benedict's 1946 book The Chrysanthemum and the Sword was influential in shaping subsequent portraits and stereotypes about Japanese values. In anthropology, the book popularized the distinction between guilt and shame cultures. It portrayed Japanese culture as being based on hierarchies between superiors and subordinates, as well as having an emphasis on interpersonal relationships with close others.[8]

The research culminating in the publication of The Chrysanthemum and the Sword was done during the Second World War when the United States and Japan were on opposite sides of the conflict. This situation influenced the research methodology used, as Benedict had to rely on interviews with a relatively low number of Japanese Americans, as well as on documents from wartime Japan. Because of these methodological problems, the book has been criticised for not distinguishing culture from ideology, as well as for relying on unreliable samples.[9]

In the 1970s Japanese psychoanalyst Takeo Doi published the book The Anatomy of Dependence, which elaborated on the honne–tatemae divide between public expression and private thoughts or feelings.[10] In Japanese mythology, the gods display human emotions, such as love and anger.[11]

Japanese children learn from their earliest days that human fulfillment comes from close association with others. Children learn early to recognize that they are part of an interdependent society, beginning in the family and later extending to larger groups such as neighborhood, school, playground, community, and company.

Dependence on others is a natural part of the human condition; it is viewed negatively only when the social obligations (giri) it creates are too onerous to fulfill, leading to, for example, suicide, which is a topic of great elaboration in Japanese history and culture. However, in the early part of the 21st century, school bullying has become a topic of very great concern.[12]

Education

Japanese adults are more likely to consider self-directness-related traits such as independence, individual responsibility, perseverance and imagination as being important goals in the education of children than are adults from most other cultures. On the other hand, Japanese adults are less likely to value traits such as religious faith or obedience as worthwhile goals for educating children in comparison with adults from other cultures. The degree of importance given by Japanese adults to practical values such as hard work and thrift or civic values like tolerance and altruism as part of child education is similar with that given by adults from most other cultures.[14]

According to a global study realized by Michael Minkov and his collaborators using samples from 54 countries representing all major world regions, the advice that adults give (in the case they are parents) or would give (in the case they have no children) to their children is in accordance to the general features of the culture in which they live. Like cultural differences in values and norms related to other domains, cultural differences about child education goals form two indexes called individualism versus collectivism and flexibility versus monumentalism. Japanese adults consider individualistic traits as being more important in child education than parents from other cultures, except from Western Europe. Flexibility traits such as adaptation to changing circumstances and self-improvement were more likely to be selected as important by Japanese adults than by adults from any other culture included in the study.[13]

See also

References

- "WVS Database". www.worldvaluessurvey.org. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- Minkov, Michael; Dutt, Pinaki; Schachner, Michael; Morales, Oswaldo; Sanchez, Carlos; Jandosova, Janar; Khassenbekov, Yerlan; Mudd, Ben (2017). "A revision of Hofstede's individualism-collectivism dimension". Cross Cultural & Strategic Management. 24 (3): 29. doi:10.1108/ccsm-11-2016-0197. ISSN 2059-5794.

- Welzel, Christian (2013). "Chapter 2. Mapping Differences". Freedom Rising. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 87. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139540919. ISBN 978-1-139-54091-9.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Beugelsdijk, Sjoerd; Welzel, Chris (2018-10-02). "Dimensions and Dynamics of National Culture: Synthesizing Hofstede With Inglehart". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 49 (10): 1485. doi:10.1177/0022022118798505. ISSN 0022-0221. PMC 6191680. PMID 30369633.

- Welzel, Christian (2011). "The Asian Values Thesis Revisited: Evidence from the World Values Surveys". Japanese Journal of Political Science. 12 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1017/s1468109910000277. ISSN 1468-1099.

- Minkov, Michael; Bond, Michael H.; Dutt, Pinaki; Schachner, Michael; Morales, Oswaldo; Sanchez, Carlos; Jandosova, Janar; Khassenbekov, Yerlan; Mudd, Ben (2017-08-29). "A Reconsideration of Hofstede's Fifth Dimension: New Flexibility Versus Monumentalism Data From 54 Countries". Cross-Cultural Research. 52 (3): 309–333. doi:10.1177/1069397117727488. ISSN 1069-3971. S2CID 149071152.

- Takano, Yohtaro; Osaka, Eiko (1999). "An unsupported common view: Comparing Japan and the U.S. on individualism/collectivism". Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2 (3): 311–341. doi:10.1111/1467-839x.00043. ISSN 1367-2223.

- Befu, H. (1980). A critique of the group model of Japanese society. Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice, (5/6), pp. 29–43.

- Ryang, Sonia (2002). "Chrysanthemum's Strange Life: Ruth Benedict in Postwar Japan". Asian Anthropology. 1 (1): 87–116. doi:10.1080/1683478x.2002.10552522. ISSN 1683-478X. PMID 17896441. S2CID 9878218.

- Takeo Doi, The Anatomy of Dependence: Exploring an area of the Japanese psyche – feelings of indulgence. Kodansha International Ltd.: 1973.

- Chamberlain, B.H. (1883). A Translation of the "Ko-Ji-Ki".

- "School bullying in Japan". BBC. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- Minkov, Michael; Dutt, Pinaki; Schachner, Michael; Jandosova, Janar; Khassenbekov, Yerlan; Morales, Oswaldo; Sanchez, Carlos Javier; Mudd, Ben (2018-04-04). "What Values and Traits Do Parents Teach to Their Children? New Data from 54 Countries". Comparative Sociology. 17 (2): 221–252. doi:10.1163/15691330-12341456. ISSN 1569-1322.

- Bond, Michael Harris; Lun, Vivian Miu-Chi (2014). "Citizen-making: The role of national goals for socializing children". Social Science Research. 44: 75–85. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.11.002. ISSN 0049-089X. PMID 24468435.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. – Library of Congress Country Studies.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. – Library of Congress Country Studies.