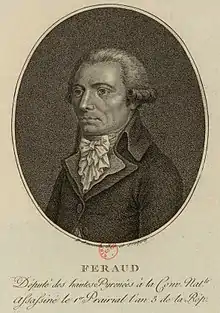

Jean-Bertrand Féraud

Jean Bertrand Féraud, (Arreau 4 August 1759 or 1764 - Paris 20 May 1795)[1][2] was a French politician of the French revolutionary era.

Early life

Jean Bertrand was the son of Jean-Baptiste Féraud, notary royal, and his wife Jeanne-Marie Casteret. His uncle Félix Féraud, also a notary, was secretary to the last meeting of the Estates of Quatre-Vallées in Arreau in 1789. He studied law, read the Encyclopédistes, and became a freemason. When the National Guard was formed in Arreau, he joined it at once and became a captain. In this capacity, he was sent to Paris to take part in the Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790.

Political career

A member of the Jacobins, close to Robespierre and Danton, Jean Bertrand Féraud was elected to the National Convention in 1792 from Hautes-Pyrénées. He was elected 5th of 6 deputies, with 145 votes out of 22 cast.[3]

He protested against the expulsion of the Girondins. He delivered a public speech on 9 Germinal Year I (29 March 1793) to the People's Society of Tarbes, at the church of Saint Jean, where the pope was burned in effigy. In May 1793 the Convention appointed him representant en mission to the Army of the Pyrenees where he was injured charging at the head of a column.[4] He carried with him a decree forbidding on pain of death the use or storing of gold or silver money and requiring all exchanges to use the assignat. On 6 September 1793 he was named representant en mission to the Army of the Rhine and the Army of the Moselle which was striking into Germany. He received his orders from Lazare Carnot as well as directly from the Committee of Public Safety.

In the Convention, he demanded the death penalty for hoarders, and at the end of the trial of Louis XVI he voted for the death penalty without appeal or reprieve,[5] but he also attacked Jean-Paul Marat, accusing him of arson, pillage, murder and anarchy. He managed to escape the proscription which fell on most of his Girondin allies because he was on mission in the countryside. Attacked on his return to Paris for having voted against Marat and his Girondin associations, he defended himself based on his record with the armies.

During the Thermidorean reaction, he joined the opponents of Robespierre and, together with Paul Barras and his troops, he broke into the Hôtel de Ville to search out the Montagnards in hiding there.[6] After this he occupied himself with the reorganisation of the Committee of Public Safety and the Committee of General Security. He was then sent as a representant en mission to the Army of the North.Antoine Merlin de Thionville described him as 'the maddest colleague you could dream of.'

Death

In the winter and spring of Year III (1795), agriculture and trade were in chaos and the currency was rapidly devaluing. Townspeople were starving as the prices of staple foods rose. The Convention, which had mobilised its armies against external threats and deployed them to repress rebellions in the provinces, could hardly contain the unrest in Paris. During the Revolt of 1 Prairial Year III the crowds forced their way into the Convention's sessions to demand bread.

Newly placed in charge of supplies for Paris, Féraud tried to harangue the crowd while waiting for reinforcements from the National Guard, but a woman in the crowd, incensed, shot him dead with a pistol. The crowd cut off his head, hoisted it on a pike, and then carried it aloft into the chamber of the Convention in front of its President[7] - who was not Boissy d'Anglas as shown in a famous painting by Fragonard, but Theodore Vernier.[8] This was the first and only time that a legislator was killed by the Paris mob.[9]

In the tumult, a 50-year-old locksmith's assistant named Jean Tinelle was arrested and condemned to death on 5 Prairial Year III for having carried the head on the pike. He was the 2,807th and final person to be condemned to death by the Revolutionary Tribunal before it was suppressed.[10]

There are various extant representations of Féraud's death, including engravings, paintings and sketches, as well as numerous accounts in newspapers and letters.[11]

References

- http://parismuseescollections.paris.fr/fr/musee-carnavalet/oeuvres/jean-bertrand-feraud-1759-1795-depute-a-la-convention-1793-1795-1795#infos-principales accessed 16/04/2017

- http://www2.assemblee-nationale.fr/sycomore/fiche/%28num_dept%29/13027 accessed 16/04/2-17

- http://www2.assemblee-nationale.fr/sycomore/fiche/(num_dept)/13027 accessed 17/04/2017

- Jean B. Robert, Vie politique de tous les députés à la Convention nationale, pendant et après la Révolution Paris 1814 p.139

- Jean B. Robert, Vie politique de tous les députés à la Convention nationale, pendant et après la Révolution p.139 Paris 1814

- http://www2.assemblee-nationale.fr/sycomore/fiche/(num_dept)/13027 accessed 17/04/2017

- Gregory Fremont-Barnes, Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760-1815, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007 p.594

- M. Mignet, History of the French Revolution, from 1789 to 1814, David Bogue, 1846 p.290

- Micah Alpaugh, Non-Violence and the French Revolution: Political Demonstrations in Paris, 1787–1795, Cambridge University Press, 2014 p.173

- Channaud, Liste générale et très-exacte de tous ceux qui ont été condamnés à mort par le Tribunal Révolutionnaire établi à Paris, 1795, vol.2 p.27

- including this letter from Louvet to Villenave, four days after his death