Jean Baptiste Beaubien

Jean Baptiste Beaubien (September 5, 1787 - January 5, 1864),[1] a multi-lingual fur-trader born in Detroit, Michigan, became an early resident of what became Chicago, Illinois, as well as an early civic and militia leader in Cook County, Illinois during the Black Hawk War, before moving to Du Page County, Illinois in his final years.[2][3][4]

Jean Baptiste Beaubien | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | September 5, 1787 Detroit, Michigan |

| Died | January 5, 1864 (aged 76) Naperville, Illinois |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Rank | captain, colonel, brigadier general |

| Battles/wars | Blackhawk War |

| Spouse(s) | Mah-naw-bun-no-quah Josette LaFramboise Louise Pinney |

Early and family life

Jean Baptiste Beaubien was born in Detroit to the former Marie-Josephette Douaire De Bondy, and her husband, Joseph Cuillerier Beaubien, of a prominent local French-Canadian family.[5] The couple had 10 children, and his father also had 15 children from a prior marriage.[6] His younger brother Mark Beaubien (1800-1881) would also move to Chicago in 1826 and achieve some prominence for his Sauganash Hotel.[7] Unlike his friend and competitor, John Kinzie, Beaubien does not appear to have owned slaves, but he did employ free persons of color in 1830.[8]

Jean Beaubien married four times, beginning in 1804. He survived three wives and possibly sired as many as 20 children. His first wife, as with many traders of the era, was a Native American woman, whose name no longer survives, only that she died giving birth to their daughter Marie.[9] Beaubien married his second wife, Mah-naw-bun-no-quah, also of the Odawa people in 1807; her father (or brother) Shabbona was Odawa and had married a Potawatomi woman from a village southwest of what became Chicago in Beaubien's lifetime. Their first son, Charles Henry Beaubien (1807-1858) was born in Chicago, and their second son Madore Beaubien (1809-1883) was born at the Grand River, Michigan trading post but would live in Chicago most of his life. In March 1812 the widower wed Josette LaFramboise (1796-1845), whose family had moved to Chicago from Milwaukee, although they wed on Mackinac Island at the other end of Lake Michigan. Among their eleven children were sons Philip Beaubien (d. 1888), William S. Beaubien (1836-1911), and Alexander Beaubien (1822-1907).[10] Beaubien married New Yorker Louise Pinion (1838-1910) in 1855, who would survive him.[11] They had a son Isidore Beaubien (1856-1934), and daughters Pauline (1861-1941) and Clothilde (1863-1941).[12]

Career

Beaubien learned the fur trading business from Joseph Bailly, who had a trading post on the Grand River in modern-day Michigan. Bailly provided Beaubien with a basic education, as he did with his metis trainee, Alexander Robinson, although unlike Beaubien Robinson never learned to write any European language (but used his own script to keep track of his accounts). By 1800, Beaubien had his own trading house in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[13] By 1806, Bailly and Robinson had a trading post in the Lake Calumet region (now part of Chicago).

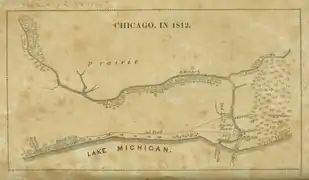

Fort Dearborn

Beaubien first visited Fort Dearborn, which later became the heart of downtown Chicago, shortly after its construction in 1804, but did not buy property there until 1812.[14] In April 1812, he left with his new wife Josette La Framboise and her metis family, all of whom returned to Milwaukee after unfriendly Winnebago killed and scalped several Caucasian settlers on an outlying farm, in what turned out to be a prelude of the Fort Dearborn Massacre of August 15, 1812.[15] Fellow trader John Kinzie, a friend of the fort's commander Nathan Heald, moved his family into the fort, and in early August warned Heald against obeying an evacuation order after the War of 1812 began; Heald's disregard of that advice and compliance with the order to move to Fort Wayne led to the massacre. Meanwhile, in June, Kinzie had killed interpreter Jean LaLime who was a member of a rival faction within the fort, and fled to Milwaukee, where he was greeted with suspicion and found those Indians both anti-American and planning to join western Indians under the direction of British trader Robert Dickson at Green Bay and war against the Americans. After returning to Chicago and failing to convince commander Heald to stay in the fort, Kinzie ultimately enlisted fellow trader Alexander Robinson, who eventually managed to evacuate some survivors to Grand River and Detroit.

Beaubien, Robinson and Bailly continued to trade during the conflict, supplied by Dickson rather than his American competitors.[16] In January 1814, an American expedition led by Robert Forsyth (John Kinzie's half-brother) captured Bailly and three other traders at St. Joseph. John Kinzie then traveled to St. Joseph, where he convinced several native American leaders to travel to Greenville, Ohio to attend an American peace conference which led to the Treaty of Greenville (1814), although other Native leaders (particularly Main Poc refused)[17]

Chicago founder

When the U.S. Army returned to rebuild Ft. Dearborn in 1816, Beaubien also returned to Chicago. By 1818 he was an agent of the American Fur Company, usurping Kinzie's former position. However, he continued to cooperate with Kinzie on other business ventures, and Kinzie's Virginia-raised son (by his first wife), James Kinzie, would operate trading posts at Milwaukee and Racine for the American Fur Company). Beaubien purchased a house or cabin south of the Fort Dearborn ruins, which he transformed into a barn in 1817 after erecting a new residence and small trading post.[18][19]

Beaubien continued to travel, trading at Milwaukee and Green Bay, Wisconsin, but thereafter always returned to his Chicago base. By 1822, John Crafts (the former trader for the Conant & Mack company of Detroit), became the American Fur Company's chief trader in Chicago, and Beaubien as well as Kinzie worked for him as sub-agents. After the U.S. Government ended its factor system for trading with the Indians, Beaubien would acquire the former U.S. Factorhouse, originally a part of the second Fort Dearborn, from the American Fur Company in 1823 for $500.[13] In the first Chicago tax roll, in 1825, Beaubien was the town's wealthiest man, with property valued at $1000. He hosted the first town election in 1825 as well as the first general election in 1826.[20] However, as the American Fur Company grew into a monopoly in Chicago, the fur trade went into a decline, as local supplies of fur-bearing animals became exhausted soon after invention of the steel trap. Instead, traders soon received much of the annuity money distributed to cooperating Potawatomis and others pursuant to various treaties, liquor sales became very important, and the American Fur Company received reimbursement for much scrip its agents received from natives. Although Crafts died of malaria in Chicago in 1825, Beaubien and Kinzie (while feuding) continued until 1828. Then, the animal decline, as well as an influx of white settlers into the ceded Potawatomi lands caused American Fur Company operations in the Chicago Region to end abruptly(around the time John Kinzie died of a stroke in January 1828).[21]

Prominent citizen and officer

However, Beaubien refused to leave Chicago as Indian Country vanished. He had recruited a company of militia in 1827 in response to a scare about Winnebago attacks.[22] The following year, the local court in Peoria appointed Beaubien administrator of John Kinzie's estate; in 1829 he became the public administrator of the estates of Francois La Framboise Jr., Indian agent Alexander Wolcott and others; Beaubien also was one of three local election judges in 1830.[22] In 1829, surveyors for the Illinois and Michigan Canal were charged with platting towns on the route. During the winter of 1831-32, Beaubien became the president of the Chicago Debating Society.[13] Of course, Beaubien (and his brother and sons) were among the "500 Chicagoans" found in the census that preceded formal incorporation of the Town of Chicago in 1833.[22]

Meanwhile, the Sauk warrior Black Hawk gained support from remaining Potawatomis in northern Illinois and Wisconsin, including Billy Caldwell, displacing from power natives and metis whom Beaubien had long befriended, such as Alexander Robinson, Shabbona and Joseph La Framboise.[23] John Kinzie's half-brother, Thomas Forsyth, who had been the Indian agent for the Sauk and Fox people in Western Illinois (and lived in St. Louis) was rather abruptly dismissed as part of a shake-up within the Andrew Jackson administration, leading to an U.S. Army intelligence failure as tensions worsened.

When the Black Hawk War broke out in 1832, Beaubien again raised a company of about twenty-five men and became their captain.[24] The company worked alongside a group of Pottawatomie scouts, and the war proved short-lived. In the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, negotiated by Caldwell, Robinson and others who advocated compensated removal (particularly after the Indian Removal Act of 1830), Beaubien served as a witness. The Kinzie and Forsyth families received more than $50,000 (although John Kinzie had already died and Thomas Forsyth would die in 1833), the American Fur Company received $17,000 to cover Potawatomi debts, and individual traders also received compensation (Beaubien himself received either $250 or $3000 for debts under the treaty).[22] In 1833, Beaubien ran to become one of the new town's trustees, but lost. The following year, he won election as the first colonel of the Cook County militia (it later became the 60th Illinois Militia Regiment). He also donated two lots on which were built St. Mary's Catholic Church, the city's first.[25]

Beaubien land claim litigation

In 1835, during a real estate boom and after Robert A. Kinzie (the trader's son) had success claiming a different downtown tract, Beaubien seemingly purchased the site of Fort Dearborn (75.69 acres) through the local government land agent for $94.61, although his two previous attempts had received letters of rejection on the grounds that it was a military reservation.[26][27] Unlike his purchase of the first carriage in town, or the second piano (for his daughters' use),[22] this led to litigation, specifically his downstate lawyer's attempt to evict the fort's commandant, Major Lafayette Wilcox.[28]

Future Illinois governor Thomas Ford was the initial judge, who pointed out that the General Land Office had failed to act after Beaubien had sent the new registration certificate to Washington and asked for a formal land patent. He invalidated Beaubien's claim as incomplete.[29] When Beaubien appealed, the Illinois Supreme Court (in an opinion drafted by his friend Theophilus W. Smith) found his claim valid on the grounds that the state legislature had never authorized the military reservation. However, the United States Supreme Court invalidated the Illinois decision, deciding the federal government's bounty in allowing pre-existing land claims had been misused, and that the government had properly established the military reservation.[30] Senator and future Illinois Supreme Court Chief Justice Sidney Breese was among Beaubien's lawyers, as were Washington D.C. attorneys Francis Scott Key and Daniel Webster, but they were opposed by Attorney General Felix Grundy and Charles Butler, his predecessor' brother, now representing a group of land speculators.

Following the decision, the U.S. District Court ordered Beaubien's payment returned, the military realized the fort unnecessary since Native Americans had left the area, and the General Land Office proceeded to ready to ready the property for subdivision and public auction as the "Fort Dearborn Addition to Chicago" (reserving only space for a lighthouse and quarters for the harbormaster). The subsequent sale of 233 lots raised $106,042.16 for the federal government, despite the decline of real estate prices after the Panic of 1837.[31] Nonetheless, Chicagoans objected when attorney James H. Collins, who had assisted the government's case against Beaubien's claim, bought five of the six lots on which Beaubien had erected his home seventeen-plus years earlier, and Beaubien could only purchase one of them, for $225. Either Beaubien then sold his lot when he couldn't buy the rest, or Collins actually evicted Beaubien from his Michigan Avenue home in 1839.[32][33] However, Collins was later less successful in his lawsuit against the Illinois Central Railway for encroaching on his lakefront property, and when the federal government formally abandoned the lighthouse and harbor area in 1854, Beaubien's friend, Congressman John Wentworth secured special legislation allowing Beaubien to patent those nine lots.[34][35]

Later years

After that legal defeat, Beaubien moved from the town of Chicago to a farm still in Cook County, Illinois near the portage to the Des Plaines River, what was then called "Hardscrabble" and later Chicago's Bridgeport neighborhood. Accounts differ as to whether he simply sold the lot he mad managed to purchase at the 1836 land sale, or was evicted from his remaining buildings in Chicago. The court also assessed legal costs against him for losing, which proved a financial problem for years. Some accounts indicate that Beaubien's farm from 1840-1850 was near that of his long-time metis friend and fellow trader Alexander Robinson, also on the Des Plaines river. Despite these legal troubles, in 1850, Beaubien received a militia commission with the title of "brigadier general". Command of the Illinois militia was later transferred to lieutenant colonel Seth Johnson.[13] One historian indicates Beaubien remained on that farm for a decade, but moved to Chicago's West Side in 1855, as he married his fourth wife.[36] One issue could be the expansion of Chicago's boundaries, as part of Robinson's farm was annexed to the city's West Side. All agree that Beaubien moved his family from Cook County to what became Naperville, Illinois in 1858, near the DuPage River in DuPage County.

Death and legacy

Beaubien died there at some time in January 1863 or 1864, survived by his fourth wife, as well as many children and grandchildren. He is buried with his third wife in his family's cemetery, established in 1845 in what became Lisle in DuPage County.[12] The Chicago History Center has an 1825 portrait of Beaubien, as well as some of his papers which survived the Great Chicago Fire.[37][38] A small Chicago street near the lakefront, "Beaubien Court" is named after the founder and gave access to the Illinois Central Railroad's freight warehouses.[39] The downtown Chicago historical marker shown above was erected in 1937 as part of the centennial of Chicago's charter,[40] The Chicago Public Schools named a north side elementary school to honor Beaubien.[41] The Cook County Forest Preserve District named 279 acres with access to the Little Calumet River and the man-made 19 acre Flatfoot Lake on the south side near the Bishop Ford Freeway "Beaubien Woods."[42]

References

- See note on talk page re various dates.

- "Chicago in the Middle Ground". www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Retrieved Feb 13, 2019.

- "Early Chicago". Retrieved Feb 13, 2019.

- Ann Durkin Keating, Rising Up from Indian County: the Battle of Fort Dearborn and the Birth of Chicago (University of Chicago Press 2012) pp. 67-68 ISBN 9780226428963

- Gilbert J. Garraghan, "Early Catholicity in Chicago," Illinois Catholic Historical Review, Vol. 1, p. 26 (1918)available at https://books.google.com/books?id=hpYOAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA26

- Ulrich Danckers, Jane Meredith et al., Early Chicago (Inland Press, River Forest Illinois, 2000) p. 68 ISBN 9780967582306

- Early Chicago

- 1830 U.S. Federal Census for Peoria, Putnam County, Illinois (pp. 5 and 6 of 10)

- Keating p. 67

- earlychicago.com names them all; the family gravestone pictured on findagrave.com also names four who died as infants.

- Her surname is transcribed "Pennean" on the typed Cook County marriage/death records online, and "Penney" on earlychicago.com.

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/30125414/john-baptiste-beaubien

- Andreas, Alfred Theodore (1884). History of Chicago: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time. I. A. T. Andreas.

- History of Early Chicago Vol. 1, p.84, available at https://archive.org/details/historyofchicago01inandr

- Keating p. 100, 125-126

- However, "Jean B. Beaubien" is listed as a sergeant in 1 Reg't (Godfroy's) Michigan Militia during the War of 1812 according to a text-only collection on ancestry.com

- Keating pp. 191-192

- Keating pp. 215, 218-219

- History of Early Chicago p.

- Keating p. 226

- Keating p. 220

- "EarlyChicagoHOME". www.earlychicago.com. Retrieved Feb 13, 2019.

- Keating pp. 226-227

- An admittedly incomplete listing of Black Hawk War veterans in Illinois archives shows Beaubien's son, Madore Beaubien, serving as a lieutenant in Boardman's Company during that war, but does not show his father.https://www.ilsos.gov/isaveterans/blackHawkSearch.do

- Carl B. Roden, "The Beaubien Claim", Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society Vol. 42, No. 2 (Jun., 1949), pp. 150-154, 162

- Roden, pp. 155-156

- Andreas p.85

- John Jackson ex dem. Murray McConnell v. Lafayette Wilcox, 2 Ill. 344 (1836) (McConnell was Beaubien's lessee, and had subleased it to Jackson)

- John Wentworth, "Fort Dearborn" an address delivered to the Chicago Historical Society on May 21, 1881 in Edward Gay Mason, Illinois in the Eighteenth Century: Kaskaskia and Its Parish ..., Volume 16 (Chicago:Fergus Printing 1881) p. 39 available at https://books.google.com/books?id=PR5JAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA39&lpg

- Wilcox v. Jackson, 13 U.S. (Peters) 498

- Roden, pp. 157-161

- Andreas p. 86

- Garraghan p. 26 n.33 cites Henry Hurlbut's Chicago Antiquities pp. 302-336 and Daily American June 18, 1839, but gives no legal citation

- Roden pp.160-165

- According to ancestry.com, the petition raised in the 3rd session of the 25th Congress, journal page 305, was tabled.

- Roden p. 165

- "Jean Baptiste Beaubien papers". Explore Chicago Collections. Retrieved Feb 13, 2019.

- "Miniature portrait of Jean Baptiste Beaubien :: Museum Collection". digitalcollection.chicagohistory.org. Retrieved Feb 13, 2019.

- Roden pp. 165-166

- "Jean Baptiste Beaubien". Read the Plaque. Retrieved Feb 13, 2019.

- "Beaubien Elementary – One School, One Family". Retrieved Feb 13, 2019.

- "Beaubien Woods". Forest Preserves of Cook County. Retrieved Feb 13, 2019.