Daniel Webster

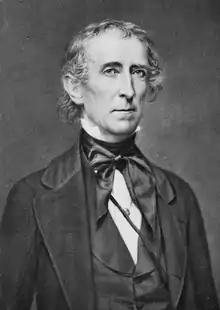

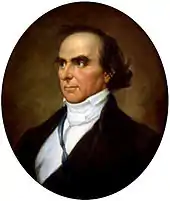

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore. As one of the most prominent American lawyers of the 19th century, he argued over 200 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court between 1814 and his death in 1852. During his life, he was a member of the Federalist Party, the National Republican Party, and the Whig Party.

Daniel Webster | |

|---|---|

| |

| 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office July 23, 1850 – October 24, 1852 | |

| President | Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | John M. Clayton |

| Succeeded by | Edward Everett |

| In office March 6, 1841 – May 8, 1843 | |

| President | William Henry Harrison John Tyler |

| Preceded by | John Forsyth |

| Succeeded by | Abel P. Upshur |

| Chair of the Senate Finance Committee | |

| In office December 2, 1833 – December 5, 1836[1] | |

| Preceded by | John Forsyth |

| Succeeded by | Silas Wright |

| United States Senator from Massachusetts | |

| In office March 4, 1845 – July 22, 1850 | |

| Preceded by | Rufus Choate |

| Succeeded by | Robert Charles Winthrop |

| In office June 8, 1827 – February 22, 1841 | |

| Preceded by | Elijah H. Mills |

| Succeeded by | Rufus Choate |

| Chair of the House Judiciary Committee | |

| In office 1823–1827 | |

| Preceded by | Hugh Nelson |

| Succeeded by | Philip Pendleton Barbour |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1823 – May 30, 1827 | |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Gorham |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Gorham |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Hampshire's at-large district | |

| In office March 4, 1813 – March 3, 1817 | |

| Preceded by | George Sullivan |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Livermore |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 18, 1782 Salisbury, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | October 24, 1852 (aged 70) Marshfield, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Federalist (before 1825) National Republican (1825–1833) Whig (1833–1852) |

| Spouse(s) | Grace Fletcher Caroline LeRoy Webster |

| Children | 5, including Fletcher |

| Education | Phillips Exeter Academy Dartmouth College (BA) |

| Signature | |

Born in New Hampshire in 1782, Webster established a successful legal practice in Portsmouth, New Hampshire after undergoing a legal apprenticeship. He emerged as a prominent opponent of the War of 1812 and won election to the United States House of Representatives, where he served as a leader of the Federalist Party. Webster left office after two terms and relocated to Boston, Massachusetts. He became a leading attorney before the Supreme Court of the United States, winning cases such as Dartmouth College v. Woodward, McCulloch v. Maryland, and Gibbons v. Ogden. Webster returned to the House in 1823 and became a key supporter of President John Quincy Adams. He won election to the United States Senate in 1827 and worked with Henry Clay to build the National Republican Party in support of Adams.

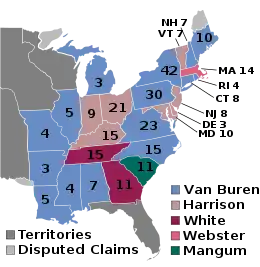

After Andrew Jackson defeated Adams in the 1828 presidential election, Webster became a leading opponent of Jackson's domestic policies. He strongly objected to the theory of nullification espoused by John C. Calhoun, and his Second Reply to Hayne speech is widely regarded as one of the greatest speeches ever delivered in Congress. Webster supported Jackson's defiant response to the Nullification Crisis, but broke with the president due to disagreements over the Second Bank of the United States. Webster joined with other Jackson opponents in forming the Whig Party, and unsuccessfully ran in the 1836 presidential election. He supported Harrison in the 1840 presidential election and was appointed secretary of state after Harrison took office. Unlike the other members of Harrison's Cabinet, he continued to serve under President Tyler after Tyler broke with congressional Whigs. As secretary of state, Webster negotiated the Webster–Ashburton Treaty, which settled border disputes with Britain.

Webster returned to the Senate in 1845 and resumed his status as a leading congressional Whig. During the Mexican–American War, he emerged as a leader of the "Cotton Whigs," a faction of Northern Whigs that emphasized good relations with the South over anti-slavery policies. In 1850, President Fillmore appointed Webster as secretary of state, and Webster contributed to the passage of the Compromise of 1850, which settled several territorial issues and enacted a new fugitive slave law. The Compromise proved unpopular in much of the North and undermined Webster's standing in his home state. Webster sought the Whig nomination in the 1852 presidential election, but a split between supporters of Fillmore and Webster led to the nomination of General Winfield Scott. Webster is widely regarded as an important and talented attorney, orator, and politician, but historians and observers have offered mixed opinions on his moral qualities and ability as a national leader.

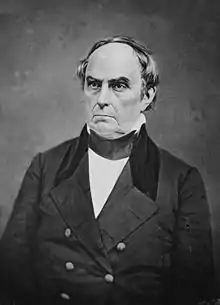

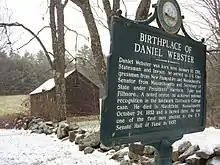

Early life

Daniel Webster was born on January 18, 1782, in Salisbury, New Hampshire, at a location within the present-day city of Franklin. He was the son of Abigail (née Eastman) and Ebenezer Webster, a farmer and local official who served in the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War. Ebenezer's ancestor, the English-born Thomas Webster, had migrated to the United States around 1636. Ebenezer had three children from a previous marriage who survived to maturity, as well as five children from his marriage to Abigail; Webster was the second-youngest of the eight siblings.[2] Daniel was particularly close to his older brother, Ezekiel, who was born in 1780.[3] As a youth, he helped work the family farm, but was frequently in poor health. With the encouragement of his parents and tutors, he often read works by authors such as Alexander Pope and Isaac Watts.[4]

In 1796, he attended Phillips Exeter Academy, a preparatory school in Exeter, New Hampshire.[5] After studying the classics and other subjects for several months under a clergyman, Webster was admitted to Dartmouth College in 1797.[6] During his time at Dartmouth, he managed the school newspaper and emerged as a strong public speaker.[7] He was chosen Fourth of July orator in Hanover, the college town, in 1800, and in his speech appears the substance of the political principles for the development of which he became famous.[8] Like his father, and like many other New England farmers, Webster was firmly devoted to the Federalist Party and favored a strong central government.[9] He graduated from Dartmouth in 1801 and was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.[10]

After graduating from Dartmouth, he apprenticed under Salisbury lawyer Thomas W. Thompson.[11] Though unenthusiastic about studying the law, he believed that becoming a lawyer would allow him to "live comfortably" and avoid the bouts of poverty that had afflicted his father.[12] In order to help support his brother Ezekiel's study at Dartmouth, Daniel temporarily resigned from the law office to work as a schoolteacher at Fryeburg Academy in Maine.[13] In 1804, he obtained a position in Boston under the prominent attorney Christopher Gore. Clerking for Gore—who was involved in international, national, and state politics—he learned about many legal and political subjects and met numerous New England politicians.[14] He grew to love Boston, and, in 1805, was admitted to the bar.[15]

Rise to prominence

Immediately after winning admission to the bar, Daniel set up a legal practice in Boscawen, New Hampshire.[16] He became increasingly involved in politics and began to speak locally in support of Federalist causes and candidates.[17] After his father's death in 1806, he handed over his practice to his brother, Ezekiel, and opened a new practice in the larger town of Portsmouth.[18] Over the decade-long period he lived in Portsmouth, he handled over 1700 cases, becoming one of the most prominent attorneys in New Hampshire.[19] Along with two other lawyers, he was appointed to revise the New Hampshire criminal code and devise regulations for state prisons.[20]

During this time the ongoing Napoleonic Wars began to more strongly affect Americans, as Britain attacked American shipping and impressed American sailors. President Thomas Jefferson retaliated with the Embargo Act of 1807, stopping all trade to both Britain and France. As New England relied on commerce with the two nations, the region strongly suffered from the embargo, and Webster wrote an anonymous pamphlet attacking Jefferson's policies.[21] He also campaigned for various Federalist candidates, including presidential candidate Charles C. Pinckney and gubernatorial candidate Jeremiah Smith. Although Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party dominated national elections, the Federalist Party was competitive throughout the states of New England.[22] In 1812, the United States declared war against Britain, beginning the War of 1812. On July 4, 1812, Webster was invited to give a speech before the Washington Benevolent Society. His speech, which strongly attacked the war but warned against secession, was reprinted in newspapers throughout New England.[23]

After the speech, he was selected as a delegate to the Rockingham Convention, a local assembly that issued a report critical of Jefferson's Democratic-Republican successor, James Madison.[24] The Rockingham Memorial, which was largely written by Webster, challenged Madison's reasons for going to war, argued that France had been just as culpable for attacks against American shipping as the British had been, and raised the specter of secession. The Rockingham Memorial gained nationwide notoriety as a document exemplifying New England's opposition to the war.[25] After the convention, the state Federalist Party nominated him as a candidate for the House of Representatives. Though Madison won re-election in the 1812 presidential election, the Federalist-backed presidential candidate won New England, and Federalists swept the New Hampshire elections for the House of Representatives.[26]

Congressman and constitutional lawyer

First stint in the House, 1813–1817

By May 1813, when he arrived in the House of Representatives for the first time, the United States had seen numerous setbacks in the War of 1812. Nonetheless, Madison's Democratic-Republican Party dominated the Thirteenth Congress, controlling over three-fifths of the seats in the House of Representatives and over two-thirds of the seats in the Senate.[27] Webster continued to criticize the war and attacked effort to impose conscription, wartime taxes, and a new trade embargo.[28] He was appointed to a steering committee that coordinated Federalist actions in the House of Representatives and, by the end of the Thirteenth Congress, he had emerged as a respected speaker on the House floor.[29] In early 1815, the war came to an end after news of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent reached the United States.[30]

After the war, President Madison called for the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States (known as the "national bank"), the imposition of a protective tariff, and federally-financed public works. While Speaker of the House Henry Clay and Congressman John C. Calhoun worked to pass Madison's proposals, other Democratic-Republicans opposed these policies because they conflicted with the party's traditional commitment to a weaker federal government.[31] Webster favored a national bank in principle, but he voted against the bill that established the national bank because he believed that the bank should be required to remove paper banknotes issued by various state-charted banks from circulation. Before the national bank came into operation, he then led the passage of a bill that required all debts to the government to be paid in specie, Treasury notes, or notes issued by the national bank.[32] In the tariff debate, he occupied a middle ground; he favored using tariff rates to protect domestic manufacturing, but did not want tariff rates to be so high that they would harm his home state's trading concerns. Though he took an active role in crafting the tariff bill, he ultimately missed the final vote on the Tariff of 1816.[33] Seeking more lucrative legal work, he began to strongly consider relocating to Boston or New York during his time in Congress.[34] In 1816, he declined to seek another term in the House of Representatives, instead establishing a new residence in Boston. In the 1816 elections, the Federalist Party suffered numerous defeats throughout the country and Democratic-Republican candidate James Monroe was elected president.[35]

Leading lawyer

Daniel Webster (Dartmouth College v. Woodward)

Webster continued to practice law while serving in the House of Representatives, and he argued his first case before the Supreme Court of the United States in early 1814.[36] He had been highly regarded in New Hampshire since his days in Boscawen, and was respected for his service in the House of Representatives, but he came to national prominence as counsel in a number of important Supreme Court cases.[37] Between 1814 and 1852, he argued at least one case in the vast majority of the sessions of the Supreme Court; he served as counsel in a total of 223 cases, and won approximately half of those cases.[38] He also represented numerous clients outside of Supreme Court cases, including prominent individuals such as George Crowninshield, Francis Cabot Lowell, and John Jacob Astor.[39]

Though Congress was dominated by Democratic-Republicans, Chief Justice John Marshall ensured that the Federalist ideology retained a presence in the courts. Daniel quickly became skilled at articulating arguments designed to appeal to Marshall and another influential Supreme Court justice, Joseph Story.[40] He played an important role in eight of the most celebrated constitutional cases decided by the Court between 1814 and 1824. In many of these—particularly in Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819) and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)—the Supreme Court handed down decisions based largely on his arguments. Marshall's most famous declaration, "the power to tax is the power to destroy," in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), was taken from Webster's presentation against the state of Maryland. As a result of his series of successes in Supreme Court cases, many people began calling him the "Great Expounder and Defender of the Constitution."[41] He would continue to argue cases before the Supreme Court after Marshall's death in 1835, but he generally found the Taney Court to be less receptive to his arguments.[42]

In Dartmouth College v. Woodward, Webster was retained by the Federalist trustees of his alma mater, Dartmouth College, in their case against the newly elected New Hampshire Democratic-Republican state legislature. The legislature had passed new laws converting Dartmouth into a state institution, by changing the size of the college's trustee body and adding a further board of overseers, which they put into the hands of the state senate.[43] He argued that the Constitution's Contract Clause prohibited the legislature from altering the college's board of trustees. The Marshall Court, continuing with its history of limiting states' rights and reaffirming the supremacy of the constitutional protection of contract, ruled in favor of Dartmouth. The ruling set the important precedent that corporations did not, as many then held, have to justify their privileges by acting in the public interest, but were independent of the states.[44]

He remained politically active during his time out of Congress, serving as a presidential elector meeting with officials like Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, and delivering a well-received speech that attacked high tariffs.[45] With the Federalists fading away as a national party, the period of Monroe's presidency came to be known as the "Era of Good Feelings" due to the lack of partisan conflict.[35] As the Federalists failed to field a candidate in the 1820 presidential election, Webster, acting in his capacity as a presidential elector, cast his vote for Monroe.[45] He was then elected as a delegate to the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention. There he spoke in opposition to suffrage for all regardless of property ownership, arguing that power naturally follows property, and the vote should be limited accordingly; but the constitution was amended against his advice.[46] He also supported the (existing) districting of the state senate so that each seat represented an equal amount of property.[47] His performance at the convention furthered his reputation. In a letter to a mutual friend, Joseph Story wrote, "our friend Webster has gained a noble reputation. He was before known as a lawyer; but he has now secured the title of an eminent and enlightened statesman."[48] In December 1820, he delivered an enthusiastically-received address commemorating the bicentennial of the landing of the Mayflower at Plymouth Rock.[49]

Second stint in the House, 1823–1827

At the behest of Federalist leaders and the business elite in Boston, Webster agreed to run for the United States House of Representatives in 1822. He won election and returned to Congress in December 1823.[50] In recognition of his mastery of legal issues, Speaker of the House Henry Clay assigned him the chairmanship of the House Judiciary Committee. In that role, he tried to pass a bill that would relieve Supreme Court justices of having to travel to far-flung western districts, but his bill did not receive a vote in the House.[51] Seeking to re-establish his reputation for oratorical prowess on the floor of the House of Representatives, he gave a speech supporting the Greek cause in the Greek War of Independence.[52] In another speech, he attacked the bill imposing the Tariff of 1824, arguing that high tariff rates unfairly benefited manufacturing to the detriment of agriculture and commerce.[53] In a third speech, he defended the construction of internal improvements by the federal government, arguing that roads helped unite the nation both economically and in creating a "feeling truly national."[54] While a Representative, he continued accepting speaking engagements in New England, most notably his oration on the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill.[55] He also continued his legal work, though his government service required him to rely more on his law partners.[56]

In the 1824 United States presidential election, the Democratic-Republicans split among Clay, Calhoun, William H. Crawford, Andrew Jackson, and John Quincy Adams.[57] Despite their shared connection to Massachusetts, Webster had an uneasy relationship with Adams because the latter had left the Federalist Party earlier in his career;[58] for his part, Adams detested him.[59] As no candidate won a majority of the electoral vote, the 1824 election was decided in a contingent election held by the House of Representatives.[lower-alpha 1] Webster had remained neutral prior to the election, but he supported Adams in the contingent election, in large part because he viewed Jackson as completely unqualified to be president and Crawford had suffered a major stroke.[60] Along with Clay, he helped rally members of the House around Adams, and Adams was elected on the first ballot of the contingent election.[61]

In 1825, President Adams set off a partisan realignment by putting forward an ambitious domestic program, based on Clay's American System, that included a vast network of federally-funded infrastructure projects. States' rights Democratic-Republicans, including Senator Martin Van Buren and Vice President John C. Calhoun, strongly opposed the program and rallied around Jackson. While some Federalists gravitated to Jackson's camp, Webster became the leader of the pro-administration forces in the House of Representatives.[62] Supporters of Adams became known as National Republicans, while Jackson's followers coalesced into the Democratic Party. Like many Federalists, he did not immediately cast aside his partisan identity as a Federalist but embraced the American System and began to favor protective tariff rates.[63] Justus D. Doenecke indicates that his newfound support of protective tariffs was the result of "his new closeness to the rising mill-owning families of the region, the Lawrences and the Lowells."[24] He also backed the administration's defense of treaty-sanctioned Creek Indian land rights against Georgia's expansionist claims.[64]

First period in the Senate

Adams administration, 1827–1829

In 1827, the Massachusetts legislature elected him to the United States Senate. He was initially reluctant to leave the House of Representatives, where he had established seniority and a strong base of power, but ultimately accepted election to the Senate.[65] After a period of consideration, he voted for the Tariff of 1828, which raised tariff rates.[66] Prior to the 1828 presidential election, he worked with Clay to build the National Republican Party across the country. While Clay rallied support for the party in the West, he emerged as a leading National Republican in the Northeastern states.[67] Despite his efforts and those of Clay, Democratic candidate Andrew Jackson decisively defeated President Adams in the 1828 election.[68]

Jackson administration, 1829–1837

Second Reply to Hayne

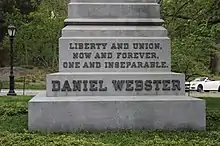

for the last time the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on States dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood! Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign of the republic... not a stripe erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured, bearing for its motto, no such miserable interrogatory as "What is all this worth?" nor those other words of delusion and folly, "Liberty first and Union afterwards"; but everywhere, spread all over in characters of living light, blazing on all its ample folds, as they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart,— Liberty and Union, now and for ever, one

and inseparable!Daniel Webster (Second Reply to Hayne)

After Jackson took office, Webster opposed most of the measures favored by the new administration, including the Indian Removal Act and the establishment of the spoils system.[69] The Jackson administration suffered from factionalism between supporters of Secretary of State Van Buren and Vice President Calhoun, the latter of whom took prominent role in propounding the doctrine of nullification. Calhoun held that the states had the power to "nullify" laws, and he and his allies sought to nullify the high tariff rates imposed by the Tariff of 1828 (which they referred to as the "Tariff of Abominations").[70] During a debate over land policy in January 1830, South Carolina Senator Robert Y. Hayne, in an effort to sway the West against the North and the tariff, accused the North of attempting to limit Western expansion for their own benefit. Hayne served as a surrogate for Vice President Calhoun, who could not himself address the Senate on the issue due to his status as the Senate's presiding officer.[71] Webster objected to the sectional attack on the North, but even more strongly objected to Hayne's pro-states' rights position. Speaking before the Senate, he articulated his belief in a "perpetual" union and attacked the institution of slavery, baiting Hayne into expounding on the doctrine of nullification on the Senate floor.[72]

Replying to his first speech, Hayne accused him of "making war upon the unoffending South," and he asserted that nullification was constitutional because the federal government was ultimately subservient to the states.[73] On January 27, Webster delivered his response, titled the Second Reply to Hayne. He held that the people, and not the states, held ultimate power, and the people had established the Constitution as the supreme law of the land. He further argued that the doctrine of nullification "approach[ed] absurdity," and, by denying power to the federal government, would effectively restore the balance of power established under the Articles of Confederation. He argued that nullification constituted treason against the United States, and would ultimately lead to civil war as state officials would call out the militia to resist federal laws and actions. He ended his speech with a call for "Liberty and Union, now and for ever, one and inseparable!"[74] The Second Reply to Hayne was reprinted thousands of times, and was favorably received throughout the country. In assessing the speech's impact and popularity, some contemporaries compared it to the Federalist Papers.[75] Three months after he delivered the Second Reply to Hayne, Calhoun openly broke with President Jackson when, in response to Jackson's toast of "Our Union, it be preserved," Calhoun replied, "The Union: Next to our liberty, the most dear."[76]

Bank War and 1832 election

By 1830, he considered Clay to be the likely National Republican nominee in the 1832 United States presidential election, though he was skeptical that Clay would be able to defeat the Democratic nominee.[77] The establishment of the Anti-Masonic Party, a third party opposed to both Jackson and Clay, added a new factor into the election. Some Anti-Masonic leaders attempted to recruit him[lower-alpha 2] to run for the presidency, but he ultimately declined to run for fear of alienating Clay and other National Republicans.[79] Instead, he undertook a subtle campaign to win the National Republican nomination, planning a tour of the Northeast and the Northwest; His angling for the presidency marked the start of an ambivalent relationship between Clay and Webster.[80] Nonetheless, he urged Clay to accept election to the Senate, and the two convinced Nicholas Biddle, the president of the national bank, to apply for an early renewal of the national bank's charter. As Jackson had a long record of opposing the national bank, both hoped to make the national bank an issue in the 1832 presidential election. Clay was formally nominated by the National Republicans in December 1831, while Jackson was nominated for a second term in 1832.[81]

Biddle requested a renewal of the national bank's charter in January 1832, setting off what became known as the "Bank War."[82] With Clay focusing on a tariff bill, Webster became the unofficial leader of pro-national bank forces in the Senate. He helped ensure that Congress approved a renewal of the charter without making any major modifications, such as a provision that would allow states to prevent the national bank from establishing branches within their borders.[83] Congress approved the charter renewal, but, as was expected, Jackson vetoed the bill in July 1832; Jackson argued the bank was unconstitutional and served to "make the rich richer and the potent more powerful." On the Senate floor, Webster attacked the veto, arguing that only the judicial branch could judge a bill's constitutionality.[84] Afterward he supported Clay's presidential campaign and continued his efforts on behalf of the national bank, but Jackson was re-elected by a decisive margin.[85]

Nullification Crisis

Though Congress replaced the "Tariff of Abominations" with the Tariff of 1832, Calhoun and his Nullifier allies remained dissatisfied with tariff rates.[86] Shortly after the 1832 presidential election, a South Carolina convention passed a resolution declaring the Tariff of 1832 to be "null, void, and no law" in South Carolina, marking the start of the Nullification Crisis. Hayne resigned from the Senate to become the governor of South Carolina, while Calhoun took Hayne's former seat in the Senate. In December 1832, Jackson issued the Proclamation to the People of South Carolina, warning that he would not allow South Carolina to defy federal law. Webster strongly approved of the Proclamation, telling an audience at Faneuil Hall that Jackson had articulated "the true principles of the Constitution," and that he would give the president "my entire and cordial support" in the crisis.[87] He strongly supported Jackson's proposed Force Bill, which would authorize the president to use force against states that attempted to obstruct federal law. At the same time, he opposed Clay's efforts to end the crisis by lowering tariff rates, as he believed that making concessions to Calhoun's forces would set a bad precedent.[88] After a spirited debate between himself and Calhoun, Congress passed the Force Bill in February 1833. Soon after, it passed the Tariff of 1833, the product of negotiations between Clay and Calhoun; the bill called for the gradual lowering of tariffs over a ten-year period. Although they symbolically "nullified" the Force Bill, South Carolina leaders accepted the new tariff law, bringing an end to the Nullification Crisis.[89]

Rise of the Whig Party and 1836 candidacy

As Calhoun drifted away from the Democratic Party and occasionally cooperated with the National Republicans to oppose Jackson, some contemporaries began to refer to Calhoun, Webster, and Clay as "the Great Triumvirate."[90] At the same time, Webster's alliance with Jackson in the Nullification Crisis caused some observers to wonder if he would join the Democratic Party or found a new party centered on their nationalistic vision.[91] Jackson's decision to remove government deposits from the national bank in late 1833 ended any possibility of a Webster-Jackson alliance and helped to solidify partisan lines.[92] As chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Webster led the Senate's effort to prevent Jackson's secretary of the treasury, Roger Taney, from removing government deposits.[93] As the national bank's charter was due to expire in 1836, before the end of Jackson's term, he attempted to save the national bank through a compromise measure, but Democrats rejected his proposal. Ultimately, the Senate was unable to prevent the deposit removals or the expiration of the national bank's charter, but it did pass resolutions censuring Jackson and Taney. Webster's decision to vote for the censure resolution caused a permanent break with Jackson.[94]

In the aftermath of the battle over the national bank, Jackson's political opponents coalesced into the Whig Party. By taking a name rooted in American and British history, the Whigs implicitly criticized Jackson as a tyrannical executive.[95] Although National Republicans like Clay and Webster formed the core of the Whig Party, Anti-Masonic leaders like William H. Seward and states' rights Democrats like John Tyler also joined the new party.[96] The Whig Party proved more durable than the National Republican Party and, along with the Democrats, the Whigs became one of the two major parties of the Second Party System, which would extend into the 1850s.[97] By 1834, Webster supporters such as Caleb Cushing, Rufus Choate, Abbott Lawrence, and Edward Everett had begun preparing for his candidacy in the 1836 presidential election.[98] With Clay showing no indication of making another run, Webster hoped to become the main Whig candidate in the 1836 election, but General William Henry Harrison and Senator Hugh Lawson White retained strong support in the West and the South, respectively. Rather than uniting behind one presidential candidate, Whig leaders settled on a strategy of running multiple candidates in order to force a contingent election in the House of Representatives.[99]

He was nominated for president by the Massachusetts legislature, but Harrison won the backing of most Whigs outside of the South. Although his reputation as a national figure was far greater than that of Harrison, many Whigs hoped that Harrison's military record would allow him to replicate Jackson's 1832 victory.[100] Webster's chances also suffered from his lingering association with the Federalist Party, his close relationship with elite politicians and businessmen, and his lack of appeal among the broad populace; Remini writes that the American public "admired and revered him but did not love or trust him."[101] With little support outside of his home state, he attempted to withdraw his presidential candidacy, but, to his eventual regret, Massachusetts Whig leaders convinced him to stay in the race.[102] Meanwhile, the 1835 Democratic National Convention nominated Van Buren, Jackson's preferred successor, for president. In the 1836 election, Van Buren won a majority of the popular and electoral vote, Harrison finished a distant second, and White carried two Southern states. Webster won only the electoral votes of Massachusetts.[103] Adding to his displeasure, he lost a major Supreme Court decision, Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, shortly after the election.[104][lower-alpha 3]

Van Buren administration, 1837–1841

Shortly after Van Buren took office, a major economic downturn known as the Panic of 1837 began. Webster and his Whig allies blamed Jackson's policies, including the Specie Circular, for the panic, but a worldwide economic downturn was a major contributing factor. The panic hit the country hard and proved disastrous for Webster's personal finances.[107] With the help of Nicholas Biddle and other friendly bankers, Webster had gone into debt to engage in land speculation on a broad scale.[108] His debt was exacerbated by his propensity for lavishly furnishing his estate and giving away money with "reckless generosity and heedless profusion," in addition to indulging the smaller-scale "passions and appetites" of gambling and alcohol.[109] The panic resulted in many creditors calling in their loans and, according to Remini, Webster would never emerge from debt after 1837.[110] Nonetheless, he remained focused on his political career.[107] While Whigs promoted the American System as the means for economic recovery, Van Buren's response to the panic focused on the practice of "strict economy and frugality."[111] Webster attacked Van Buren's proposals to address the economic crisis, including the establishment of an Independent Treasury system,[112] and he helped arrange for the rescinding of the Specie Circular.[113]

He entertained hopes of winning the Whig nomination in the 1840 United States presidential election, but ultimately declined to challenge Clay or Harrison, both of whom commanded broader support within the party.[114] He remained neutral between Clay and Harrison, instead departing for a trip to Europe, where he attended his daughter's wedding and befriended Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton.[115] While he was abroad, the 1839 Whig National Convention nominated Harrison for president. Although many Whigs favored a Harrison-Webster ticket, the convention instead nominated John Tyler of Virginia for vice president.[116] Webster served as a prominent campaign surrogate for Harrison in the 1840 election, although he disliked the party's new, popular style of campaigning that made use of songs and slogans like "Tippecanoe and Tyler too."[117] The Whigs enjoyed great success in the 1840 elections, as Harrison took a majority of the popular and electoral vote and the party won control of Congress.[118]

Secretary of State in the Tyler administration

Harrison extensively consulted Webster and Clay regarding presidential appointments, and the two Whig leaders competed to place their supporters and allies in key positions. Harrison initially hoped that Webster would serve as secretary of the treasury in order to spearhead his economic program, but Webster instead became secretary of state, giving him oversight of foreign affairs.[119] Just one month after taking office, Harrison died from pneumonia, and was succeeded by John Tyler. Though Tyler and Webster strongly differed regarding ideology (Tyler was a devotee of states' rights) and personality, they initially enjoyed a strong working relationship, partly because each saw Clay as a rival for power in the Whig Party.[120] As Tyler, a former Democrat, had long been skeptical of the need for a national bank, Webster urged Whig congressmen to back a compromise bill put forward by Secretary of the Treasury Thomas Ewing which would have re-established the national bank but restricted its branching power. Congress rejected the compromise and instead passed Clay's bill, which was subsequently vetoed by Tyler. After Tyler vetoed another Whig bill, every Cabinet member except for Webster resigned, and a caucus of Whigs voted to expel Tyler from the party in September 1841. When Webster informed Tyler that he would not resign, Tyler responded, "give me your hand on that, and now I will say to you that Henry Clay is a doomed man."[121]

Facing a hostile Congress, Tyler and Webster turned their attention to foreign policy.[122] The administration put a new emphasis on American influence in the Pacific Ocean, reaching the first U.S. treaty with China, seeking to partition Oregon Country with Britain, and announcing that the United States would oppose any attempt to colonize the Hawaiian Islands.[123] The most pressing foreign policy issue involved relations with Britain, as the United States had nearly gone to war with Britain over the Caroline affair and a border conflict between Maine and Canada.[124] Seeking improved relations with the United States, British Prime Minister Robert Peel dispatched Lord Ashburton on a special mission to the United States.[125] After extensive negotiations, the United States and Britain reached the Webster–Ashburton Treaty, which clearly delineated Maine's northern border and other sections of the U.S.-Canada border that had been in dispute.[126] Senator Thomas Hart Benton led Senate opposition to the treaty, arguing that it "needlessly and shamelessly" relinquished American territory, but few others joined Benton in voting against the treaty, and it won ratification.[127]

After mid-1841, congressional Whigs continually pressured Webster to resign, and by early 1843, Tyler had also begun to pressure Webster to leave office.[128] As Tyler moved even farther away from Whig positions and began preparing a campaign for the Democratic nomination in the 1844 United States presidential election, Webster left office in May 1843.[129] With Webster gone, Tyler turned his attention to the annexation of the Republic of Texas.[130] Clay was nominated for president at the 1844 Whig National Convention,[131] while the Democrats spurned both Tyler and former President Van Buren in favor of James K. Polk, a protege of Andrew Jackson.[132] Webster's service in the Tyler administration had badly damaged his credibility among Whigs, but he began to rebuild old alliances within the party.[133] Tyler's attempts to annex Texas became the key issue in the 1844 election, and Webster came out strongly against annexation. He campaigned on behalf of Clay, telling one crowd, "I know of no great national constitutional question; I know of no great interest of the country ... in which there is any difference between the distinguished leader of the Whig Party and myself."[134] Despite Webster's campaigning, Polk defeated Clay in a close election.[135] The election of the expansionist Polk ensured the annexation of Texas, and annexation was completed after Polk took office.[136]

Second period in the Senate

Polk administration, 1845–1849

Webster considered retiring from public office after the 1844 election, but he accepted election to the United States Senate in early 1845.[137] Webster sought to block the adoption of Polk's domestic policies, but Congress, controlled by Democrats, reduced tariff rates through the Walker tariff and re-established the Independent Treasury system. In May 1846, the Mexican–American War began after Congress, responding to a clash between U.S. and Mexican forces at the disputed Texas–Mexico border, declared war on Mexico.[138] During the war, Northern Whigs became increasingly split between "Conscience Whigs" like Charles Sumner, who strongly favored anti-slavery policies, and "Cotton Whigs" like Webster, who emphasized good relations with Southern leaders.[139] Webster had been a long-standing opponent of slavery; in an 1837 speech he called slavery a "great moral, social, and political evil," and added that he would vote against "any thing that shall extend the slavery of the African race on this continent, or add other slaveholding states to the Union."[140] But, unlike his more strongly anti-slavery constituents, he did not believe that Congress should interfere with slavery in the states, and he placed less emphasis on preventing the spread of slavery into the territories.[141] Nonetheless, because Webster opposed the acquisition of Mexican territory (with the exception of San Francisco), he voted against the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which the United States acquired the Mexican Cession.[142]

General Zachary Taylor's success in the Mexican–American War drove him to the front ranks of Whig candidates in the 1848 United States presidential election.[143] As Taylor held unclear political positions and had never been publicly affiliated with the Whig Party, Clay and Webster each launched their own bids for the presidency, but opposition from the Conscience Whigs badly damaged Webster's standing.[144] On the first ballot of the 1848 Whig National Convention Webster finished a distant fourth behind Taylor, Clay, and General Winfield Scott. Taylor ultimately won the presidential nomination on the convention's third ballot, while Millard Fillmore of New York was selected as the party's vice presidential nominee.[145] After Webster declined the request of Conscience Whigs to lead a new, anti-slavery third party, Conscience Whigs and "Barnburner" Democrats launched the Free Soil Party and nominated a ticket consisting of former President Van Buren and Charles Francis Adams. Despite having previously stated that he would not support Taylor in the 1848 presidential campaign, Webster threw his backing behind Taylor. Ultimately, Taylor won the election, defeating both Van Buren and Democratic nominee Lewis Cass.[146]

Taylor administration, 1849–1850

Daniel Webster (July 17, 1850 address to the Senate)

Having only tepidly endorsed Taylor's campaign, Webster was excluded from the new administration's Cabinet and was not consulted on major appointments.[147] After the 1848 election, the fate of the territories acquired in the Mexican-American War became a major subject of debate in Congress, as Northern and Southern leaders quarreled over the extension of slavery.[148] In January 1850, Clay introduced a plan which combined the major subjects under discussion. His legislative package included the admission of California as a free state, the cession by Texas of some of its northern and western territorial claims in return for debt relief, the establishment of New Mexico and Utah territories, a ban on the importation of slaves into the District of Columbia for sale, and a more stringent fugitive slave law.[149] The plan faced opposition from strongly pro-slavery Southern leaders like Calhoun[150] and anti-slavery Northerners like William Seward and Salmon Chase.[151] President Taylor also opposed Clay's proposal, since he favored granting California statehood immediately and denied the legitimacy of Texas's claims over New Mexico.[152]

Clay had won Webster's backing for his proposal before presenting it to Congress, and Webster provided strong support for Clay's bill in the Senate.[153] In a speech that became known as the "Seventh of March" speech, Webster attacked Northerners and Southerners alike for stirring up tensions over slavery. He admonished Northerners for obstructing the return of fugitive slaves, but attacked Southern leaders for openly contemplating secession.[154] After the speech, Webster was bitterly attacked by New England abolitionists. Theodore Parker complained, "No living man has done so much to debauch the conscience of the nation," while Horace Mann described Webster as "a fallen star! Lucifer descending from Heaven!"[155] The debate over Clay's compromise proposal continued into July 1850, when Taylor suddenly and unexpectedly died of an illness.[156]

Secretary of State in the Fillmore administration

Compromise of 1850

Millard Fillmore ascended to the presidency upon Taylor's death. Shortly after taking office, Fillmore dismissed Taylor's Cabinet appointees, named Webster as his secretary of state,[lower-alpha 4] and came out in favor of Clay's compromise.[157] Fillmore chose the remaining members of his Cabinet in consultation with Webster, and Webster became the unofficial leader in the Cabinet.[158] After Fillmore took office, Clay took a temporary leave from the Senate, but Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois took the lead in advocating for a compromise based largely on Clay's proposals.[159] On behalf of the president, Webster drafted a special message to Congress calling for an end to the crisis over the territories, and he used the power of patronage to woo potential supporters. Soon after the Fillmore administration delivered the special message, Congress passed Douglas's legislative package, which became known as the Compromise of 1850.[160]

Due to a prosperous economy and various other trends, few Whigs pushed for a revival of the national bank and other long-standing party policies during the Fillmore administration, and the Compromise of 1850 became the central political issue.[161] While Fillmore hoped to reconcile with anti-Compromise Northern Whigs, Webster sought to purge them from the party, and he frequently intervened to block the election or appointment of anti-Compromise Whigs.[162] In the North, the most controversial portion of the Compromise of 1850 was the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and Webster became closely involved in enforcing the law.[163] Disputes over fugitive slaves were widely publicized North and South, inflaming passions and raising tensions in the aftermath of the Compromise of 1850. Many of the administration's prosecutions or attempts to return slaves ended badly for the government, as in the case of Shadrach Minkins.[164] In Massachusetts, anti-slavery Whigs allied with Democrats and, in a major rebuke to Webster, elected Free Soil leader Charles Sumner to the Senate.[165]

Opening of the New York & Erie Rail Road

When the New York & Erie Rail Road was completed in May 1851, President Fillmore and several members of his cabinet, including Webster, made a special, two-day excursion run to open the railway. It is reported that Webster viewed the entire run from a rocking chair attached to a flatcar, with a steamer rug and jug of high-quality Medford rum.[166][167] At stops, he would get down and speechify.

Foreign affairs

Fillmore appointed Webster not only for his national stature and pro-Compromise position, but also for his experience in foreign affairs, and Fillmore relied on Webster to guide his administration's foreign policy.[168] The administration was particularly active in Asia and the Pacific, especially with regard to Japan, which prohibited nearly all foreign contact. In November 1852, the administration launched the Perry Expedition to force Japan to establish trade relations with the United States.[169] Perry was successful in his mission, as Japan agreed to open trade relations with the 1854 Convention of Kanagawa.[170] In the aftermath of the failed Hungarian Revolution of 1848, a diplomatic incident with the Austrian Empire arose over the Taylor administration's sympathetic actions towards the Hungarian rebels. Rather than backing down, the Fillmore administration secured the release of exiled Hungarian leader Lajos Kossuth from the Ottoman Empire and gave a banquet in Kossuth's honor.[171] The Fillmore administration also reached trade agreements with Latin American countries,[172] worked to counter British influence in Central America[173] and took measures to prevent unauthorized military expeditions against Cuba and other Latin American countries.[174] An expedition led by Narciso López precipitated a diplomatic crisis with Spain, but Fillmore, Webster, and the Spanish government worked out a series of face-saving measures that prevented an outbreak of hostilities from occurring.[175]

1852 election

Encouraged by Fillmore's professed lack of desire to pursue the Whig nomination in the 1852 United States presidential election, Webster launched another campaign for the presidency in 1851.[176] Fillmore was sympathetic to the ambitions of his secretary of state, but he was unwilling to completely rule out accepting the party's 1852 nomination, as he feared doing so would allow his rival, William Seward, to gain control of the party.[177] Another candidate emerged in the form of General Winfield Scott, who, like previously successful Whig presidential nominees William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, had earned fame for his martial accomplishments. Scott had supported the Compromise of 1850, but his association with Seward made him unacceptable to Southern Whigs.[177] As Southerners retained a lingering distrust of Webster, they threw their backing behind Fillmore.[178] Thus, Scott emerged as the preferred candidate of most Northern Whigs, Fillmore became the main candidate of Southern Whigs, and Webster was only able to win backing from a handful of delegates, most of whom were from New England.[179]

On the first presidential ballot of the 1852 Whig National Convention, Fillmore received 133 of the necessary 147 votes, while Scott won 131 and Webster won 29.[180] Although both Webster and Fillmore were willing to withdraw in favor of the other, their respective delegates at the convention were unable to unite around one candidate, and Scott took the nomination on the 53rd ballot.[181] Webster was personally devastated by the defeat, and he refused to endorse Scott's candidacy.[182] Webster allowed various third party groups to nominate him for president, although he did not openly condone these efforts.[183] Scott proved to be a poor candidate, and he suffered the worst defeat in Whig history, losing to Democratic nominee Franklin Pierce.[184] Thousands of anti-Scott Whigs and members of the nativist Native American Party cast their vote for Webster.[185]

Personal life, family, and religious views

Daniel Webster (May 22, 1852)

_-_Gilbert_Stuart.jpg.webp)

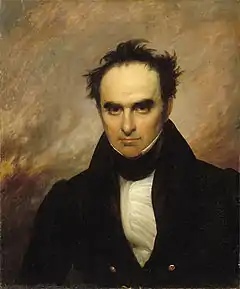

In 1808, Webster married Grace Fletcher, a schoolteacher and the daughter of a New Hampshire clergyman.[186] Between 1810 and 1822, Daniel and Grace had five children: Grace, Daniel "Fletcher", Julia, Edward, and Charles. Grace and Charles died before reaching adulthood.[187] Webster's wife, Grace, died in January 1828 due to a cancerous tumor,[188] and Webster suffered another loss when his brother, Ezekiel, died in April 1829.[189] In December 1829, Webster married Caroline LeRoy, the 32-year-old daughter of a New York merchant. They remained married until Webster's death, and she lived until 1882.[190] After the death of his first wife, Webster was frequently the subject of rumors in Washington regarding his alleged promiscuity; many suspected that the painter Sarah Goodridge, with whom he had a close relationship, was his mistress.[191]

Webster and his family lived in Portsmouth until 1816, when they relocated to Boston.[192] In 1831, Webster purchased a 150-acre estate (now known as the Thomas–Webster Estate) in Marshfield, Massachusetts. In the ensuing years, Webster spent much of his earnings making various improvements to his estate, and he made it his primary residence in 1837. After 1829, Webster also owned his father's home, The Elms, in Franklin, New Hampshire.[193] Webster's older son, Fletcher, married a niece of Joseph Story, established a profitable law practice, served as chief clerk of the State Department, and was the only one of his siblings to outlive his father.[194] Fletcher died at the 1862 Second Battle of Bull Run while serving as a colonel in the Union army.[195] Webster's younger son, Edward, died of typhoid fever in January 1848 while serving in the Mexican-American War.[196] Webster's daughter, Julia, married Samuel Appleton Appleton, but died of tuberculosis in April 1848.[197] All of Webster's living descendants trace their ancestry through Julia.[195]

Conflicting opinions have been voiced as to his religion. The Unitarian Universalist Church, citing Unitarianism in America from 1902, claim him as their own.[198] Another source, the 1856 biography The American Statesman: The Life and Character of Daniel Webster, proclaims him an avowed orthodox Trinitarian, baptized and raised in an Orthodox Congregational Church, and who died a member of the Episcopal Church.[199] Remini writes that, though Webster occasionally attended other churches, he remained closely affiliated with the Congregational church throughout his life. In an 1807 letter to a Congregational pastor, Webster wrote, "I believe in the utter inability of any human being to work out his own Salvation, without the constant aids of the spirit of all grace. ... Although I have great respect for some other forms of worship, I believe the Congregational mode, on the whole, to be preferable to any other."[200]

Death

By early 1852, Webster had begun to suffer from cirrhosis of the liver, and his poor health increasingly made it difficult for him to serve as secretary of state. In September 1852, Webster returned to his Marshfield estate, where his health continued to decline due to cirrhosis and a subdural hematoma.[201] He died at Marshfield on October 24, 1852 and is buried in Winslow Cemetery near his estate. His last words were: "I still live."[202]

Legacy

Historical evaluations

Daniel Webster (March 7, 1850 A Plea for Harmony and Peace)

Remini writes that "whether men hated or admired [Webster], all agreed ... on the majesty of his oratory, the immensity of his intellectual powers, and the primacy of his constitutional knowledge."[203] Ralph Waldo Emerson, who had criticized Webster following the Seventh of March address, remarked in the immediate aftermath of his death that Webster was "the completest man", and that "nature had not in our days or not since Napoleon, cut out such a masterpiece." In Profiles in Courage, John F. Kennedy called Webster's defense of the Compromise of 1850, despite the risk to his presidential ambitions and the denunciations he faced from the north, one of the "greatest acts of courageous principle" in the history of the Senate. Conversely, Seventh of March has been criticized by Lodge who contrasted the speech's support of the 1850 compromise with his 1833 rejection of similar measures. "While he was brave and true and wise in 1833," said Lodge, "in 1850 he was not only inconsistent, but that he erred deeply in policy and statesmanship" in his advocacy of a policy that "made war inevitable by encouraging slave-holders to believe that they could always obtain anything they wanted by a sufficient show of violence."[204]

Several historians suggest Webster failed to exercise leadership for any political issue or vision. Lodge describes Webster's "susceptibility to outside influences that formed such an odd trait in the character of a man so imperious by nature. When acting alone, he spoke his own opinions. When in a situation where public opinion was concentrated against him, he submitted to modifications of his views with a curious and indolent indifference."[205] Similarly, Arthur Schlesinger cites Webster's letter requesting retainers for fighting for the national bank, one of his most inveterate causes; he then asks how Webster could "expect the American people to follow him through hell or high water when he would not lead unless someone made up a purse for him?"[206] Remini writes that "Webster was a thoroughgoing elitist—and he reveled in it."[207]

Webster retains his high prestige in recent historiography. Baxter argues that his nationalistic view of the union as one and inseparable from liberty helped the union to triumph over the states-rights Confederacy, making it his greatest contribution.[208] In 1959, the Senate named Webster, Clay, Calhoun, Robert M. La Follette, and Robert A. Taft as the five greatest senators in history.[209] However Bartlett, emphasizing Webster's private life, says his great oratorical achievements were in part undercut by his improvidence with money, his excessively opulent lifestyle, and his numerous conflict of interest situations.[210] Remini points out that Webster's historical orations taught Americans their history before textbooks were widely available.[211]

While evaluations on his political career vary, Webster is widely praised for his talent as an orator and attorney. Former Solicitor General Seth P. Waxman writes that "in the realm of advocacy, Webster doesn't merely sit in the Pantheon: He is Zeus himself."[212] Kennedy praised Webster's "ability to make alive and supreme the latent sense of oneness, of union, that all Americans felt but few could express."[213][214] Webster's "Reply to Hayne" in 1830 was generally regarded as "the most eloquent speech ever delivered in Congress," and was a stock exercise for oratory students for 75 years.[215] Schlesinger, however, notes that he is also an example of the limitations of formal oratory: Congress heard Webster or Clay with admiration, but they rarely prevailed at the vote. Plainer speech and party solidarity were more effective, and Webster never approached Jackson's popular appeal.[216]

Memorials

Webster's legacy has been commemorated by numerous means, including the Daniel Webster Highway and Mount Webster in New Hampshire. His statue stands in the National Statuary Hall Collection, while another statue stands in Central Park. The USS Daniel Webster (SSBN-626) and the SS Daniel Webster were both named for Webster. The first Webster postage stamp was issued in 1870. In all, Daniel Webster is honored on 14 different US postage issues, more than most U.S. Presidents.[217][218] There are towns named for Webster in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, and Michigan, among other states. Seven counties or parishes are named for Webster.

In media

Webster is the major character in a fictional short story, The Devil and Daniel Webster, by Stephen Vincent Benét. It serves as the basis for a one-act opera of the same name written by American composer Douglas Moore.

On film, Webster has been portrayed by

- George MacQuarrie in The Mighty Barnum (1934)

- Sidney Toler in The Gorgeous Hussy (1936)

- Emmett Vogan in The Monroe Doctrine (1939)

- Harry Humphries in Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940)

- Edward Arnold in The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941)

- Anthony Hopkins in Shortcut to Happiness (2003)

See also

Notes

- Under the Constitution, the House can select from the top three electoral vote winners in a contingent election for president. Thus, Jackson, Adams, and Crawford were eligible to be selected, while Clay was not. Calhoun dropped out early in the campaign and won election as vice president.

- Unlike Jackson and Clay, he was not a member of a Masonic fraternity[78]

- Aside from Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, other major cases he argued before the Taney Court include Thurlow v. Massachusetts[105] and Luther v. Borden.[106]

- Webster's service in the Fillmore administration made him the first individual to serve as secretary of state under three different presidents. James G. Blaine would later match Webster's feat of serving as secretary of state under three different presidents.

References

- "Membership of the Finance Committee (By Congress and Session)" (PDF). United States Senate Committee on Finance. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- Remini 1997, pp. 29–33.

- Remini 1997, pp. 47–48.

- Remini 1997, pp. 35–37.

- Remini 1997, pp. 38–40.

- Remini 1997, pp. 41–42.

- Remini 1997, pp. 49–53.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Webster, Daniel". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 459–462.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Webster, Daniel". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 459–462. - Remini 1997, pp. 53–54.

- Remini 1997, pp. 55–56.

- Remini 1997, pp. 58–59.

- Remini 1997, pp. 58–59, 66–67.

- Remini 1997, pp. 60–61.

- Lodge 1883, p. 12.

- Remini 1997, pp. 73–77.

- Remini 1997, pp. 78–79.

- Cheek, H. Lee Jr. "Webster, Daniel." In Schultz, David, ed. Encyclopedia of American Law,New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2002. Facts On File, Inc. American History Online

- Remini 1997, pp. 83–84.

- Remini 1997, pp. 89–90.

- Remini 1997, p. 97.

- Norton (2005). A People & A Nation. p. 228.

- Remini 1997, pp. 95–96.

- Remini 1997, pp. 96–99.

- "Daniel Webster." Discovering Biography. Online Edition. Gale, 2003. Student Resource Center. Thomson Gale. June 16, 2006.

- Remini 1997, pp. 100–101.

- Remini 1997, pp. 101–102.

- Remini 1997, pp. 103–105.

- Remini 1997, pp. 107–109, 112–113.

- Remini 1997, pp. 109, 120–122.

- Remini 1997, pp. 131–132.

- Remini 1997, pp. 135–136, 141.

- Remini 1997, pp. 136–137.

- Remini 1997, pp. 137–140.

- Remini 1997, p. 131.

- Remini 1997, pp. 141–145.

- Remini 1997, pp. 115–117.

- "Daniel Webster", in American Eras, Volume 5: The Reform Era and Eastern U.S. Development, 1815–1850, Gale Research, 1998. Student Resource Center. Thomson Gale. June 16, 2006.

- Remini 1997, p. 119.

- Remini 1997, pp. 145–146.

- Remini 1997, pp. 116–118.

- Remini 1997, pp. 162, 208.

- Remini 1997, pp. 443–444.

- Baker, Thomas E. "Dartmouth College v. Woodward." In Schultz, David, ed. Encyclopedia of American Law. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2002. Facts On File, Inc. American History Online.

- O'Brien, Patrick K., gen. ed. "Dartmouth College case." Encyclopedia of World History. Copyright George Philip Limited. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2000. Facts On File, Inc. World History Online. Schlesinger Age of Jackson. p. 324–5.

- Remini 1997, pp. 170–171.

- Schlesinger 1945, pp. 12–15.

- Lodge 1883, p. 113.

- Lodge 1883, p. 38.

- Remini 1997, pp. 178–185.

- Remini 1997, pp. 198–200.

- Remini 1997, pp. 213–214.

- Remini 1997, pp. 210–211, 215–217.

- Remini 1997, pp. 221–224.

- Remini 1997, pp. 243–244.

- Remini 1997, pp. 247–251.

- Remini 1997, p. 254.

- Remini 1997, pp. 211–212.

- Remini 1997, pp. 197.

- Remini 1997, p. 226.

- Remini 1997, pp. 230–231, 237.

- Remini 1997, pp. 238–241.

- Remini 1997, pp. 255–261.

- Remini 1997, pp. 269–272.

- Lodge 1883, p. 49.

- Remini 1997, pp. 277–281.

- Remini 1997, pp. 295–299.

- Remini 1997, pp. 273–277.

- Remini 1997, pp. 301–302.

- Remini 1997, pp. 313–315, 334.

- Remini 1997, pp. 313–314.

- Schouler, James (1891). History of the United States. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company.

- Remini 1997, pp. 318–320.

- Remini 1997, pp. 321–324.

- Remini 1997, pp. 325–328.

- Remini 1997, pp. 329–330.

- Remini 1997, p. 335.

- Remini 1997, pp. 336–337, 341.

- Remini 1997, p. 339.

- Remini 1997, pp. 339–340.

- Remini 1997, pp. 341–342.

- Remini 1997, pp. 344–345.

- Remini 1997, pp. 345, 356.

- Remini 1997, pp. 360–363.

- Remini 1997, pp. 363–368.

- Remini 1997, pp. 370–371.

- Howe 2007, pp. 400–404.

- Remini 1997, pp. 372–374.

- Remini 1997, pp. 374–377.

- Remini 1997, pp. 381–387.

- Remini 1997, p. 359.

- Remini 1997, pp. 374, 387–388.

- Cole 1993, pp. 202–203.

- Remini 1997, pp. 401, 408–409.

- Remini 1997, pp. 410–412.

- Remini 1997, pp. 413–415, 420.

- Cole 1993, pp. 211–213.

- Howe 2007, p. 390.

- Remini 1997, pp. 425–426.

- Remini 1997, pp. 427–429.

- Remini 1997, pp. 430–431, 439–440.

- Remini 1997, pp. 450–451.

- Remini 1997, pp. 444–448.

- Remini 1997, pp. 448–449.

- Remini 1997, pp. 459–461.

- Remini 1997, p. 605.

- Remini 1997, p. 640.

- Remini 1997, pp. 466–467.

- Remini 1997, pp. 452–453.

- Lodge 1883, p. 118.

- Remini 1997, p. 466.

- Howe 2007, pp. 505–506.

- Remini 1997, pp. 470–472.

- Remini 1997, pp. 478–479.

- Remini 1997, pp. 483–484.

- Remini 1997, pp. 487–497.

- Remini 1997, pp. 501–502.

- Remini 1997, pp. 505–507.

- Howe 2007, p. 575.

- Remini 1997, pp. 511–515.

- Remini 1997, pp. 521–524.

- Remini 1997, pp. 524–531.

- Peterson 1989, pp. 113, 145.

- Peterson 1989, pp. 135–143.

- Remini 1997, pp. 518–519.

- Remini 1997, pp. 542–543.

- Peterson 1989, pp. 122–123, 128.

- Peterson 1989, pp. 129–130.

- Remini 1997, pp. 551, 583.

- Remini 1997, pp. 583–584.

- Peterson 1989, pp. 186–187.

- Peterson 1989, pp. 221–222.

- Howe 2007, pp. 683–684.

- Remini 1997, pp. 584–586.

- Remini 1997, pp. 591–596.

- Peterson 1989, pp. 243–244.

- Peterson 1989, pp. 255–258.

- Remini 1997, pp. 599–602.

- Remini 1997, pp. 618–623.

- Remini 1997, pp. 624–626.

- Remini 1997, p. 464.

- Remini 1997, pp. 664–665.

- Remini 1997, p. 646.

- Remini 1997, pp. 631–632.

- Remini 1997, pp. 637–639.

- Remini 1997, pp. 651–652.

- Remini 1997, pp. 653–656.

- Remini 1997, pp. 656–660.

- Remini 1997, pp. 658–659.

- Smith 1988, pp. 111–112.

- Smith 1988, pp. 112–113, 117.

- Smith 1988, pp. 119–120.

- Smith 1988, pp. 136–142.

- Remini 1997, pp. 665–666.

- Remini 1997, pp. 669–673.

- Kennedy (2004). Profiles in Courage. pp. 69–70.

- Remini 1997, p. 683.

- Remini 1997, pp. 684–687.

- Remini 1997, pp. 689–690.

- Smith 1988, pp. 177–181.

- Remini 1997, pp. 691–695.

- Holt 1999, pp. 686–688, 738.

- Holt 1999, pp. 635–636.

- Remini 1997, pp. 695–696.

- Smith 1988, pp. 208–213.

- Remini 1997, pp. 706–707.

- Stover, John F. (1995). History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Purdue University Press. p. 74. ISBN 9781557530660.

- Stover, John F. (1999). The Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads. Psychology Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780415921404.

- Remini 1997, p. 689.

- Smith 1988, pp. 96–98.

- Remini 1997, p. 713.

- Remini 1997, pp. 698–705.

- Remini 1997, p. 722.

- Remini 1997, pp. 713–716.

- Remini 1997, pp. 718–720.

- Smith 1988, pp. 227–229.

- Remini 1997, pp. 724–725.

- Smith 1988, pp. 239–244.

- Holt 1999, pp. 681–682.

- Remini 1997, pp. 735–736.

- Smith 1988, pp. 244–247.

- Remini 1997, pp. 736–739.

- Remini 1997, pp. 739–741, 755.

- Gienapp 1988, pp. 20–21.

- Holt 1999, pp. 754–755.

- Gienapp 1988, pp. 29–30.

- Remini 1997, pp. 86–89.

- Remini 1997, p. 13.

- Remini 1997, pp. 285, 288–291.

- Remini 1997, p. 305.

- Remini 1997, pp. 310–311, 758.

- Remini 1997, pp. 306–309.

- Remini 1997, pp. 144–145.

- Remini 1997, pp. 346–352.

- Remini 1997, pp. 452, 520.

- Remini 1997, p. 758.

- Remini 1997, pp. 626–627, 642.

- Remini 1997, pp. 485, 643.

- Cooke, George (1902). Unitarianism in America. Kessinger Publishing. p. 271. ISBN 1-4191-9210-8.

- Banvard, Joseph (1856). The American Statesman: The Life and Character of Daniel Webster. pp. 302, 303, 306.

- Remini 1997, pp. 86–88.

- Remini 1997, pp. 753–756, 761.

- Remini 1997, pp. 759–760.

- Remini 1997, p. 9.

- Lodge 1883, pp. 103, 105.

- Lodge 1883, p. 18.

- Schlesinger 1945, p. 84.

- Remini 1997, pp. 352–353.

- Maurice G. Baxter, One and Inseparable: Daniel Webster and the Union (1984)

- "The "Famous Five"". United States Senate. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- Irving H. Bartlett, Daniel Webster (1978)

- Remini 1997, p. 187.

- Waxman, Seth P. (2001). "In the Shadow of Daniel Webster: Arguing Appeals in the Twenty-First Century". J. App. Prac. & Process. 3: 523.

- Kennedy (2004). Profiles in Courage. p. 58.

- Lodge 1883, p. 66.

- Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union (1947) 1:288.

- Schlesinger 1945, pp. 50–52.

- "Smithsonian National Postal Museum". Arago.si.edu. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- Scotts US Stamp Catalogue

Works cited

- Cole, Donald B. (1993). The Presidency of Andrew Jackson. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0600-9.

- Gienapp, William E. (1988). The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195055016.

- Holt, Michael (1999). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199772032.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743797.

- Lodge, Henry Cabot (1883). Daniel Webster. Houghton, Mifflin. OCLC 16440580.

- Peterson, Norma Lois (1989). The Presidencies of William Henry Harrison and John Tyler. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0400-5.

- Remini, Robert V. (1997). Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04552-8.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. (1945). The Age of Jackson. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 9780316773430.

- Smith, Elbert B. (1988). The Presidencies of Zachary Taylor & Millard Fillmore. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0362-6.

Further reading

- Bartlett, Irving H. Daniel Webster (1978) online edition

- Baxter, Maurice G. "Webster, Daniel"; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000. online edition at academic libraries

- Baxter, Maurice G. One and Inseparable: Daniel Webster and the Union. (1984).

- Brands, H. W. (2018). Heirs of the Founders: The Epic Rivalry of Henry Clay, John Calhoun and Daniel Webster, the Second Generation of American Giants. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0385542548.

- Current, Richard Nelson. Daniel Webster and the Rise of National Conservatism (1955), short biography

- Curtis, George Ticknor. Life of Daniel Webster (1870), useful for quotations online edition vol 1; online edition vol 2

- Fuess, Claude Moore Daniel Webster. (2 vols. 1930). scholarly biography

- Remini, Robert V. Daniel Webster: The Man and His Time (1997)

- Ogg, Frederic Austin. Daniel Webster (1914) online edition, old scholarly biography

- Peterson, Merrill D. The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, and Calhoun (1983)

Specialized scholarly studies

- Arntson, Paul, and Craig R. Smith. "The Seventh of March Address: A Mediating Influence." Southern Speech Communication Journal 40 (Spring 1975): 288–301.

- Bartlett, Irving H. "Daniel Webster as a Symbolic Hero." New England Quarterly 45 (December 1972): 484–507. in JSTOR

- Baxter, Maurice G. Daniel Webster and the Supreme Court (1966)

- Birkner, Michael. "Daniel Webster and the Crisis of Union, 1850." Historical New Hampshire 37 (Summer/Fall 1982): 151–73.

- Brauer, Kinley J. "The Webster-Lawrence Feud: A Study in Politics and Ambitions." Historian 29 (November 1966): 34–59.

- Brown, Thomas. "Daniel Webster: Conservative Whig." In Politics and Statesmanship: Essays on the American Whig Party, (1985) pp. 49–92. online

- Carey, Robert Lincoln. Daniel Webster as an Economist. (1929). online edition

- Dalzell, Robert F. Jr. Daniel Webster and the Trial of American Nationalism, 1843–1852. (1973).

- Dubofsky, Melvyn. "Daniel Webster and the Whig Theory of Economic Growth: 1828–1848." New England Quarterly 42 (December 1969): 551–72. in JSTOR

- Eisenstadt, Arthur A. "Daniel Webster and the Seventh of March." Southern Speech Journal 20 (Winter 1954): 136–47.

- Fields, Wayne. "The Reply to Hayne: Daniel Webster and the Rhetoric of Stewardship." Political Theory 11 (February 1983): 5–28. in JSTOR

- Foster, Herbert D. "Webster's Seventh of March Speech and the Secession Movement, 1850." American Historical Review 27 (January 1922): 245–70. in JSTOR

- Formisano, Ronald P. The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s (1983)

- Jones, Howard. To the Webster–Ashburton Treaty: A Study in Anglo-American Relations, 1783–1843. (1977). 251 pp.

- Nathans, Sydney. Daniel Webster and Jacksonian Democracy. (1973).

- Nathans, Sydney. "Daniel Webster, Massachusetts Man," New England Quarterly 39 (June 1966): 161–81. in JSTOR

- Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union: Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847–1852 (1947), highly detailed narrative of national politics.

- Parish, Peter J. "Daniel Webster, New England, and the West." Journal of American History 54 (December 1967): 524–49. in JSTOR

- Prince, Carl E., and Seth Taylor. "Daniel Webster, the Boston Associates, and the U.S. Government's Role in the Industrializing Process, 1815–1830." Journal of the Early Republic 2 (Fall 1982): 283–99. in JSTOR

- Rakestraw, Donald A. Daniel Webster: Defender of Peace. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2018.

- Shade, William G. "The Second Party System" in Paul Kleppner ed., Evolution of American Electoral Systems (1983)

- Sheidley, Harlow W. "The Webster–Hayne Debate: Recasting New England's Sectionalism." New England Quarterly 1994 67(1): 5–29. in Jstor

- Sheidley, Harlow W. "'Congress only can declare war' and 'the President is Commander in Chief': Daniel Webster and the War Power." Diplomatic History 12 (Fall 1988): 383–409.

- Shewmaker, Kenneth E. "Forging the 'Great Chain': Daniel Webster and the Origins of American Foreign Policy toward East Asia and the Pacific, 1841–1852." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 129 (September 1985): 225–59.

- Shewmaker, Kenneth E. ed. Daniel Webster: "The Completest Man. (1990), specialized studies by scholars

- Simpson, Brooks D. "Daniel Webster and the Cult of the Constitution," Journal of American Culture 15 (Spring 1992): 15–23. online in Blackwell Synergy

- Smith, Craig R. "Daniel Webster's Epideictic Speaking: A Study in Emerging Whig Virtues" online edition

- Smith, Craig R. Daniel Webster and the Oratory of Civil Religion. (2005) 300pp

- Smith, Craig R. "Daniel Webster's July 17th Address: A Mediating Influence in the 1850 Compromise," Quarterly Journal of Speech 71 (August 1985): 349–61.

- Smith, Craig R. Defender of the Union: The Oratory of Daniel Webster. (1989).

- Szasz, Ferenc M. "Daniel Webster – Architect of America's 'Civil Religion'," Historical New Hampshire 34 (Fall/Winter 1979): 223–43.

- Wilson, Major L. "Of Time and the Union: Webster and His Critics in the Crisis of 1850." Civil War History 14 (December 1968): 293–306. ch 1 of Wilson, Space, Time, and Freedom: The Quest for Nationality and the Irrepressible Conflict, 1815–1861 (1974) online edition

Primary sources

- Select Speeches of Daniel Webster 1817–1845 edited by A. J. George, (1903) online at Project Gutenberg. Contains: Defence of the Kennistons; The Dartmouth College Case; First Settlement of New England; The Bunker Hill Monument; The Reply to Hayne; The Murder of Captain Joseph White; The Constitution Not a Compact Between Sovereign States; Speech at Saratoga; and Eulogy on Mr. Justice Story.

- The works of Daniel Webster edited in 6 vol. by Edward Everett, Boston: Little, Brown and company, 1853. online edition

- McIntyre, J. W., ed. The Writings and Speeches of Daniel Webster. 18 vols. (1903). vol 8 online

- Tefft, B. F., ed. The Speeches of Daniel Webster and His Master-Pieces. Alta ed. Philadelphia, Penn.: Porter and Coates, 1854.

- Van Tyne, Claude H., ed. The Letters of Daniel Webster, from Documents Owned Principally by the New Hampshire Historical Society (1902). online edition

- Webster, Fletcher, ed. The Private Correspondence of Daniel Webster. 2 vols. 1857. online edition vol 1

- Wiltse, Charles M., Harold D. Moser, and Kenneth E. Shewmaker (Diplomatic papers), eds., The Papers of Daniel Webster, (1974–1989). Published for Dartmouth College by the University Press of New England. ser. 1. Correspondence: v. 1. 1798–1824. v. 2. 1825–1829. v. 3. 1830–1834. v. 4. 1835–1839. v. 5. 1840–1843. v. 6. 1844–1849. v. 7. 1850–1852 – ser. 2. Legal papers: v. 1. The New Hampshire practice. v. 2. The Boston practice. v. 3. The federal practice (2 v.) – ser. 3. Diplomatic papers: v. 1. 1841–1843. v. 2. 1850–1852 – ser. 4. Speeches and formal writings: v. 1. 1800–1833. v. 2. 1834–1852.

External links

- Daniel Webster Estate

- Daniel Webster: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Works by Daniel Webster at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Daniel Webster at Internet Archive

- Webster–Hayne debate, 1830 on nullification & tariff

- The works of Daniel Webster... 6 vol, 1853 edition

- The private correspondence of Daniel Webster ed. by Fletcher Webster. 2v 1857 edition

- Portrait of Daniel Webster, painted by William Willard circa 1839-1985

- United States Congress. "Daniel Webster (id: W000238)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Daniel Webster at Find a Grave

- Daniel Webster Speeches Collection from the University of Missouri Division of Special Collections and Rare Books