Jim Berkland

James O. Berkland (July 31, 1930 – July 22, 2016) was an American geologist[1] who controversially claimed to be able to predict earthquakes, including the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake and 1994 Northridge Earthquake[2] and who popularized the idea that some people are earthquake sensitive. He was profiled in a popular 2006 book as The Man Who Predicts Earthquakes. The book includes a chapter that notes "Many of Berkland's theories--based on tides, moons, disoriented pets, lost cats and dogs, and magnetic field changes--were factors in the great Indian Ocean quake-tsunami disaster on December 26, 2004."[3] but neither his methods nor his predictions have been published in any scientific journals for peer review. His results have been disputed by peers, with other scientists going so far as calling him a crank[4] and a clown.[5] His Family included his Wife Jan Berkland, children, Krista and Jay, and Grandchildren Kara and Jace Beyer.

Career

Jim Berkland studied geology at the University of California, Berkeley earning the Bachelor of Arts degree in 1958. Thereafter he worked for the United States Geological Survey while pursuing graduate study. In 1964, he took a position at the United States Bureau of Reclamation.[6] After further graduate study, he taught for a year at Appalachian State University, 1972–1973, then returned to California to work as County Geologist for Santa Clara County from 1973 until he retired in 1994.[7]

Predictions

Berkland's predictions have been either self-published in his newsletter or website, or announced in various interviews or speaking engagements.[8] His notoriety arose from an interview published in the Gilroy Dispatch on October 13, 1989, where he predicted that an earthquake with a magnitude between 3.5 and 6.0 would occur in the San Francisco Bay Area between October 14 and October 21.[9] The 6.9-magnitude Loma Prieta earthquake occurred on October 17, just four days later. Berkland claims that government officials told him not to make any more predictions, fearing mass panic, and he was suspended for two months from his Santa Clara County geology position in late October, 1989.

Interviewed on Fox News in March 2011, Berkland predicted a massive earthquake in California for sometime between March 19 and March 26, 2011. He cited as factors the highest tides in 18 years and the proximity of the Moon, suggesting that the quake will most likely strike on Saturday, March 19, 2011.[10] No such quake occurred.[11]

He has also claimed to have predicted the 1980 M 7.2 Eureka earthquake just fourteen hours before it hit, but the tape-recording documenting this "had somehow been lost in the mail".[12]

Up to June 2010 Berkland made many predictions in his newsletter and on his website, for which he has claimed a "75 percent accuracy rate".[13]

Methodology

Berkland has been predicting earthquakes since the 1970s, but his method has not been described in the scientific literature (he claims because of censorship and a conspiracy of prejudicial reviewers[15]), nor in any detail in any media.[16] In 1990 he described the "Seismic Window Theory" as "correlating gravitational stresses with earthquakes" - referring to the tidal stresses in the Earth resulting from the gravitational pull of the Moon, especially at lunar perigee, when the Moon is closest to the Earth. He said there are three main processes: (1) the solid Earth tide that deforms the Earth's crust (up to three feet), (2) oceanic tides, and (3) ground water pore-pressure. Since 1979 he has also subscribed to a theory that "pets often react prior to earthquakes by running away", which he measures by monitoring the lost-and-found ads in several newspapers.[17] He claims that ads for missing animals "increase dramatically by up to 300-400 per cent" prior to earthquakes.

In 2006 Berkland's method was described[18] as the "Three Double G" system: 1) "the gravity gradient, or the forces exacted on the Earth by the gravitational pull of the Sun and the Moon." 2) "Gone Gatos" (missing cats) as indicated by advertisements in several newspapers. 3) "Geyser Gaps", seen as irregularities in the behavior of a geyser in the Napa Valley. Berkland's method has been said to also involve "a hodge-podge of factors".[19]

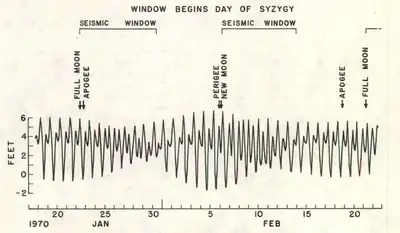

McClellan provides the most detailed description.[20] Berkland starts with two lunar syzygies each month where the Sun, Moon, and Earth are aligned (corresponding to the new Moon and full Moon). He then sets a "seismic window" eight days long, beginning from one to three days before each syzygy. The one nearest perigee, that raises the highest tides, he terms primary, the other secondary. The greatest tides happen when syzygy and perigee are less than 25 hours apart (from two to five times a year). On that basis he then predicts one or more earthquakes of a specified magnitude within each of three regions on the U.S. West Coast, and one or more earthquakes globally. The West Coast regions are:

- (a) within 140 miles from Los Angeles City Hall (34°N 118°W),

- (b) within 140 miles of Mt. Diablo (east of San Francisco; 37.9°N 121.9°W), and

- (c) anywhere in Washington or Oregon.

Then he then selects location and magnitude by considering a number of other factors, including:

- (1) unusual animal behavior

- (2) misbehaving geysers and hot springs,

- (3) extreme seasonal rainfall,

- (4) reports of symptoms from human "seismic sensitives",

- (5) magnetic fluctuations,

- (6) seismic quiet periods,

- (7) personal intuition (his so-called "MOSS predictions", or "monthly outright seismic speculations").

How Berkland evaluated his success rate prior to 1999 is unknown. Since then he has used his "dartboard" method,[21] where he takes credit not only for "bulls-eyes" (where an earthquake occurs within his windows of time, place, and magnitude), but also partial credit of 90, 80, or 70 percent for earthquakes within:

- one, two, or three days on either side of his window,

- 0.1, 0.2, or 0.3 units of magnitude,

- 10, 20, or 30 percent beyond his standard radius of 140 miles.

The product of these scores is the summary score, and any score of 70% or greater is counted as a hit.

Scientific criticism

Of methodology

Berkland's method of predicting earthquakes is based primarily on the idea that where tectonic forces have brought rock to the brink of failure earthquakes can be triggered by the tidal forces induced by the Sun and Moon, especially when they are greatest (that is, at the points of orbital syzygy, corresponding with the new Moon and full Moon). While this seems plausible, attempts to identify any such effect generally have been equivocal, possibly because various factors might not have been properly accounted for.[22] An evaluation specifically of earthquakes in the San Francisco Bay area (done by the USGS in 1980 at Berkland's request) showed a slight deficiency of earthquakes during Berkland's "seismic windows". Although that deficiency was considered statistically insignificant, the overall conclusion was that "the seismic window theory fails as a reliable method of earthquake prediction."[23] A subsequent study in 2004 found slightly more M > 7.0 earthquakes than expected in seismic windows in a ten-year period, but this evened out in longer periods, and overall syzygy considerations were found to have no predictive value.[24]

Of predictions

Berkland has said that the only real test of a predictive method is how well it performs,[26] and in this regard he claims a "75 percent accuracy rate".[27] However,[28] Berkland's "windows" are so large that they should net about three-quarters of all earthquakes even if they occurred randomly, without regard to syzygy. E.g., in a 28-day lunar cycle he has two windows of eight days each, plus six partial credit days, thus covering 22 days out of the 28.[29] (This is reminiscent of Charles Richter's pronouncement that "every earthquake takes place within 3 months of an equinox."[30]) The arbitrary inclusion of other undocumented factors makes the results nearly impossible to evaluate. One analysis that tried to evaluate his results in a consistent manner found no statistical significance, and concluded that "Berkland is not actually predicting earthquakes."[31]

Berkland's claimed "accuracy rate" is also incomplete. The societal value of any prediction method depends not only on its success rate (the proportion of total predictions that are successful), but also on the false alarm ratio (the proportion of predictions that are false), and on the hit rate (proportion of all events successfully predicted), or its inversion, the number of earthquakes missed.[32] These cannot be determined without knowing about all of the predictions made, which Berkland does not document.

See also

Further reading

- Deming, David (Spring 2007), "Earthquake Prediction, Kooks, and Syzygy: A Review of The Man Who Predicts Earthquakes", [Book review], Journal of Scientific Exploration, 21 (2): 373–382, ISSN 0892-3310.

- Hunter, Roger (September–October 2006), "Can Jim Berkland predict earthquakes?", Skeptical Inquirer, vol. 30 no. 5, pp. 47–50, archived from the original on 2016-03-07, retrieved 2016-03-09.

- McClellan, Patrick (Spring 2007), "The Man Who Predicts Earthquakes — Jim Berkland, Maverick Geologist: How His Quake Warnings Can Save Lives by Cal Orey", [Book review], Journal of Scientific Exploration, 21 (2): 383–395, ISSN 0892-3310.

- Prothero, Donald (April 2011), "Quacks and Quakes" (PDF), Skeptic Magazine, vol. 16 no. 4, pp. 26–27.

Notes

- Kallen 2016.

- Orey 2006, pp. 103-104.

- Orey 2006, pp. 144-160.

- Prothero 2011.

- Jerry Seaton, a USGS seismologist: "We've known this guy throughout his professional life, and he's distinguished himself by being a clown the entire time." Quoted in Dolan (1990), and also in Berkland (1990).

- Amanda Fehd (2005-06-28). "Living in earthquake country: Temblor once sent chunks of shoreline into Lake Tahoe". Tahoe Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- Austin Walsh (1999-10-16). "Loma Prieta predictor Jim Berkland still picking quake dates". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- McClellan 2007, p. 383.

- Deming 2007, p. 373.

- "USGS Geologist Jim Berkland predicts major California quake". CNN iReport. 16 March 2011. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2013. He also gave predictions on the Fox News Channel

- See USGS catalog of earthquakes Archived 2016-06-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- Berkland 1990.

- Orey 2006, p. 45.

- McNutt & Heaton 1981

- Berkland 1990; McClellan 2007, p. 383.

- McClellan (2007, p. 393) reports that the details of Berkland's method have to be teased out, as in a scavenger hunt.

- Berkland 1990.

- Orey 2006, p. 29.

- Hunter 2006.

- McClellan 2007, pp. 385–386.

- McClellan 2007, pp. 387–388.

- See discussion in McNutt & Heaton 1981, and also in Deming 2007, pp. 377–378.

- McNutt & Heaton 1981.

- Kennedy, Vidale & Parker 2004. Other studies (e.g., Hartzell & Heaton 1989) have found no fortnightly tidal periodicity, either globally, or for southern California specifically.

- Snieder & van Eck 1997, p. 458.

- Berkland 1990.

- Orey 2006, p. 45.

- See discussion in McClellan 2007, pp. 386–387.

- Similar criticisms apply to his handling of area and magnitude.

- Quoted in Snieder & van Eck 1997, p. 458.

- Hunter 2006, p. 49.

- See Jolliffe & Stephenson 2003, §3.2.2 for details.

Sources

- Berkland, Jim (November 29, 1990), Report to the California Commission of Earthquake Preparedness and Natural Hazards, archived from the original on March 7, 2016.

- Deming, David (2007), "Earthquake Prediction, Kooks, and Syzygy: A Review of The Man Who Predicts Earthquakes", [Book review], Journal of Scientific Exploration, 21 (2): 373–382, ISSN 0892-3310.

- Dolan, Carrie (June 5, 1990), "If He Does Confirm Your Fears, Hang Up and Call Dial-a-Prayer", Wall Street Journal, p. B1.

- Hartzell, Stephen; Heaton, Thomas (August 1989), "The Fortnightly Tide and the Tidal Triggering of Earthquakes", Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 79 (4): 1282–1286.

- Hunter, Roger (September–October 2006), "Can Jim Berkland predict earthquakes?", Skeptical Inquirer, vol. 30 no. 5, pp. 47–50, archived from the original on 2016-03-07, retrieved 2016-03-09.

- International Commission on Earthquake Forecasting for Civil Protection (30 May 2011), "Operational Earthquake Forecasting: State of Knowledge and Guidelines for Utilization", Annals of Geophysics, 54 (4): 315–391, doi:10.4401/ag-5350.

- Jolliffe, Ian T.; Stephenson, David B., eds. (2003), Forecast Verification: A Practitioner's Guide in Atmospheric Science (1st ed.), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., ISBN 0-471-49759-2.

- Kallen, Christian (July 29, 2016), "Earthquake prognosticator, Glen Ellen raconteur Jim Berkland dies at 85", Sonoma Index-TribuneCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Matthew; Vidale, John E.; Parker, Michael G. (October 2004), "Earthquakes and the Moon: Syzygy predictions fail the test", Seismological Research Letters, 75 (5): 607–612, doi:10.1785/gssrl.75.5.607

- McClellan, Patrick (2007), "The Man Who Predicts Earthquakes — Jim Berkland, Maverick Geologist: How His Quake Warnings Can Save Lives by Cal Orey", [Book review], Journal of Scientific Exploration, 21 (2): 383–395, ISSN 0892-3310.

- McNutt, Marcia; Heaton, Thomas (January 1981), "An Evaluation of the Seismic-Window Theory for Earthquake Prediction" (PDF), California Geology, 34 (1): 12–16, ISSN 0026-4555.

- Orey, Cal (2006), The Man Who Predicts Earthquakes: Jim Berkland, Maverick Geologist: How His Quake Warnings Can Save Lives, Boulder, CO: Sentient Publications, ISBN 9781591810360.

- Prothero, Donald (April 2011), "Quacks and Quakes" (PDF), Skeptic Magazine, vol. 16 no. 4, pp. 26–27.

- Schaal, Rand B. (February 1988), "An evaluation of the animal-behavior theory for earthquake predictions" (PDF), California Geology, 41 (2): 41–45, ISSN 0026-4555.

- Snieder, R.; van Eck, T. (August 1997), "Earthquake prediction: a political problem?", Geologische Rundschau, 86 (2): 446–463, doi:10.1007/s005310050153, ISSN 1432-1149

External links

- "Berkland's Web site". SyzygyJOB.com. Archived from the original on 2006-03-24. Berkland's web site was inactive since about June 2010.