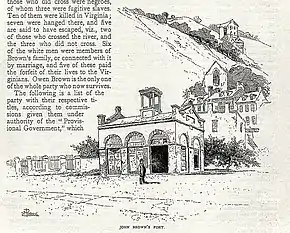

John Brown's Fort

John Brown's Fort was originally constructed in 1848 for use as a guard and fire engine house by the federal Harpers Ferry Armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia).

An 1848 military report described the building as "An engine and guard-house 35 1/2 x 24 feet, one story brick, covered with slate, and having copper gutters and down spouts…"[1] The building achieved notoriety during John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859.

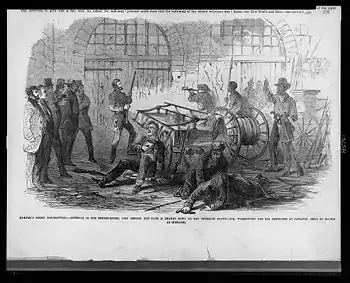

John Brown's raid

John Brown planned to capture the armory and the associated arsenal and use them to supply an army of abolitionists and run-away slave guerrillas. Beginning their raid the night of October 16, Brown and his small army of 21 men (16 white and 5 black) captured the armory and arsenal and succeeded in taking 60 citizens of Harpers Ferry hostage. The local militia and armed townspeople killed several members of the insurrection and forced Brown to take up position in the sturdy fire engine house, where Brown's men had placed several of the hostages and prepared to use the building for defense. On the night of October 17, U.S. marines and then Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee and his aide J.E.B. Stuart arrived in Harpers Ferry to put down Brown's insurrection. The next morning, using a ladder as a battering ram, the marines broke down the door and stormed the fire engine house. One marine was mortally wounded in the attack as well as several of Brown's men. Some of Brown's men managed to escape, but most were captured, including Brown, who was stabbed by the Marine commander, Lt. Green. The hostages were freed.

After the raid

The engine house was the only part of the Harper's Ferry Armory still standing after the Civil War. There was much combat in and around Harpers Ferry, which changed hands several times during the war.

To attract tourists, the words "John Brown's Fort" were painted on the engine house. It "was a tourist destination—almost a shrine—for African Americans in the late nineteenth century."[2] However, it was described thus in 1882:

The walls of the old engine-house at Harper's Ferry, where John Brown made his last stand with a dozen men against 7,000, ...now furnish an artistic background to a huge placard setting forth the virtues of somebody's liver pad. The inscription on the front of the buildlng, which tells the story of Brown's crusade, cannot be read at any distance. The advertisement of the liver pad is in letters as long as a Springfield musket. The grass grows rank in front of the historic spot, as though few pilgrim feet visited it. A clump of tan rag-weed stands in the open doorway where young Watson Brown and his brother were shot down. The roof has gone, the windows have disappeared, and there is an air of neglect and gradual decay about the spot that accords well with the stagnation of the town.[3]

In 1891, the building was sold to a buyer who wished to use it as an attraction at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, "but the venture proved a failure, simply because there was nothing which could connect the 'Brown Fort' with Chicago."[4] The building was dismantled and left on a vacant lot after the exhibition. In 1894, a movement was spearheaded by Washington D.C. journalist Kate Field to preserve the building and move it back to Harpers Ferry. It could not be moved to its original location because the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had purchased the land and covered it with an embankment in 1894.[1]

Alexander and Mary Murphy deeded 5 acres (20,000 m2) of their Harpers Ferry farm for one dollar as a relocation site, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad provided free shipping. Reconstruction of John Brown's Fort on the Murphy farm was completed by November 1895, which included the gates that surrounded the fort. The Murphy Farm was originally established September 1, 1869, and the National Park Service purchased the farm through the Trust for Public Land on December 31, 2002; it is now part of the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

A book published in 1905 refers to a "white monument" marking the spot of John Brown's Fort.[5]

On August 17, 1906, at the Murphy Farm, members of the Niagara Movement held an on-site memorial for Brown they called "John Brown Day". Over one hundred prominent African-American men and women walked past the farmhouse to the Fort's location, among them W.E.B. DuBois, Lewis Douglas, and W. T. Greener. The leader of the procession, a physician from Brooklyn named Owen Waller, removed his shoes and socks as if he were walking on holy ground.[6]

In 1909, Storer College, a college for African Americans in Harper's Ferry, bought John Brown's Fort from Alexander Murphy for $900 and moved it to the college's campus. In 1960, the National Park Service acquired the building and, in 1968, moved it once more to a location close to its original site. The Fort is now part of the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park run by the NPS and sits 150 feet (46 m) east of its original location, at 39°19′22.95″N 77°43′46.43″W.[1]

The structure cannot be considered "fully authentic" due to the number of times it has been dismantled, moved, and reassembled, each time with potential loss of original building material. It is also not an exact replica, as portions of the building were reconstructed backwards.[7]

The John Brown Museum now houses the original armory gate as well as Alexander Murphy's picture. The original armory gate was donated to the NPS by Jim Kuhn, great-great-grandson, for no money or tax benefit; the remaining gates were donated in 1997.

Controversy over bell

During a Union Army occupation of Harpers Ferry, a contingent of soldiers from Marlborough, Massachusetts, removed a bell hanging in the Harpers Ferry arsenal firehouse.. Several of those from Marlborough were in the local fire department, called the "'Torrent' Fire/Engine Company", according to the city of Marlborough website. They took the bell back to Marlborough, where it has remained. Harpers Ferry has attempted to retrieve the bell without success.[8]

In July 2011, Howard Swint, of Charleston, West Virginia, alleged that the bell was taken without authorization. In legal terms, according to Swint, it was stolen, and still belongs to the federal government. He threatened to sue the city of Marlborough in an attempt to obtain the bell for Harpers Ferry. He has drafted, but not filed his lawsuit (as of July 20, 2011).[9] However, his action has generated controversy in the Marlborough area.[10][11][12][13] Swint's arguments were published in a Massachusetts newspaper editorial column.[14]

Replica at Discovery Park of America

An approximate replica of the firehouse was built in 2012 at the Discovery Park of America museum park in Union City, Tennessee. There is a marker explaining the link with John Brown's raid.[15][16][17]

See also

References

- "Harpers Ferry National Historical Park - John Brown's Fort". www.nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- Brophy, Alfred L. (April 2008). "The Creation of Harpers Ferry". h-Net (h-Civil War). Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "General Notes". New York Times. August 20, 1882. p. 6 – via newspapers.com.

- Tate, Tilden Garnett (January 18, 1898). "The John Brown Raid. His capture, trial, execution and comments". Spirit Of Jefferson (Charles Town, West Virginia). p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- Zittle, John Henry (1905), A correct history of the John Brown invasion at Harper's Ferry, West Va., Oct. 17, 1859, p. 256

- Quarles, Benjamin (2001). Allies for Freedom & Blacks on John Brown. Da Capo Press. pp. 4–14.

[page 4] Defying stone and stubble, Waller took off his shoes and socks and walked barefoot as if he were treading on holy ground.

- Moyer, Teresa S. and Paul A. Shackel. The Making of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park: A Devil, Two Rivers, and a Dream; Rowman Altamira, 2008, p. 92

- Joan Abshire (March 12, 2008). "The John Brown Bell" (PDF).

- Howard Swint (n.d.). "IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT — NORTHERN DISTRICT OF WEST VIRGINIA". Archived from the original on 2012-11-11.

- Kendall Hatch (July 20, 2011). "Battle resumes over Marlborough's John Brown bell".

- Paul Brodeur (July 24, 2011). "Battle of the John Brown bell".

- Metrowest Daily News (July 25, 2011). "Editorial: Give back the bell".

- Paul Brodeur (July 29, 2011). "Legal reality behind Brown's Bell". Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- Howard Swint (August 3, 2011). "Howard Swint:Who Owns John Browns Bell?". The MetroWest Daily News. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- "Fire Station House at Discovery Park Of America". Dreamstime. 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- Caudle, Glenda (March 29, 2013). "DPA firehouse based on historical building" (PDF). Union City Daily Messenger.

- Hughes, Sandra (2017). "The Firehouse". Historical Markers Database.