Virginia v. John Brown

Virginia v. John Brown was a criminal trial held in Charles Town, Virginia, in October of 1859. The abolitionist John Brown was quickly prosecuted for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, murder, and inciting a slave insurrection, all part of his raid on the United States federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. (Since 1863, both Charles Town and Harpers Ferry are in West Virginia.) He was found guilty of all charges, sentenced to death, and was executed by hanging on December 2.

| Virginia v. John Brown | |

|---|---|

| |

| Decided | 31 October 1859 |

| Verdict | Guilty of all charges; sentenced to death |

| Charge |

|

| Prosecution | Andrew Hunter |

| Defence |

|

On October 16, 1859, Brown led (counting himself) 22 armed men, 5 black and 17 white, to Harpers Ferry, an important railroad and river junction. His goal was to seize the federal arsenal there and then, using the captured arms, lead a slave insurrection across the South. Brown and his men engaged in a two-day standoff with local militia and federal troops, in which ten of his men were shot or killed, five were captured, and five escaped.[1] Of Brown's three sons participating, Oliver and Watson were killed during the fight, Watson surviving in agony for another day. Owen escaped and later fought in the Union Army.

Thanks to the recently-invented telegraph, Brown's trial was the first to be reported nationally.[2]:291 In attendance, among others, were a reporter from the New York Herald and another from The Daily Exchange of Baltimore, both of whom had been in Harpers Ferry since October 18;[3][4][5][6] reports on the trial, including Brown's remarks, differ in details, showing the work of more than one hand. The coverage was so intense that reporters could dedicate whole paragraphs to the weather,[7] and the visit of Brown's wife, the night before his execution, was the subject of lengthy articles.[8][9][10][11][12]

The stories in the Herald were published unsigned, as the reporter, named House, was in Charles Town incognito in disguise, under a different name, with credentials from a Boston pro-slavery paper. He begged a visitor that knew him not to say his real name aloud.[13]

Two artists from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper were in attendance,[14] and Harper's Weekly employed a local artist and nephew of Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter, Porte Crayon (David Hunter Strother);[15][16] one of his drawings is in the Gallery, below. The illustrations were so widely distributed that Yale Literary Magazine made fun of them, publishing the drawings of "our own artist on the spot" of "Governor Wise's shoes", "John Brown's watch", and the like.[17]

Considering its aftermath, it was arguably the most important criminal trial in the history of the country, for it was closely related to the war that quickly followed. More than Brown's raid, his trial determined the fate of the Union.

According to Brian McGinty, the "Brown of history" was thus born in his trial. Had Brown died before his trial, he would have been "condemned as a madman and relegated to a footnote of history". Robert McGlone added that "the trial did magnify and exalt his image. But Brown's own efforts to fashion his ultimate public persona began long before the raid and culminated only in the weeks that followed his dramatic speech at his sentencing."[2] After his arrest, Brown engaged in extensive correspondence, readily available online today. After the conviction and sentencing, the judge permitted him to have visitors, and in his final month alive—Virginia law required that a month elapse between sentencing and execution—he gave interviews to reporters or anyone else who wanted to talk to him. All of this was facilitated by the "just and humane" jailor of Jefferson County, Captain John Avis, who "does all for his prisoners that his duty allows him to", and had a "sincere respect" for Brown.[18]:206 Brown's last meal, and the last time he saw his wife, was with the jailer's family, in their apartment at the jail.

Trial

Jurisdiction

This was the first criminal case in the United States about which where was a question of whether federal courts or state courts had jurisdiction.

The Secretary of War, after a lengthy meeting with President Buchanan, telegraphed Lee that the United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, Robert Ould, was being sent to take charge of the prisoners and bring them to justice.[19] However, Governor Wise quickly appeared in person.

President Buchanan was indifferent to where Brown and his men were tried; Ould, in his brief report, does not call for federal prosecutions, as the only relevant crimes were those few that took place within the Armory.[20] "Virginia Governor Henry Wise, on the other hand, was 'adamant' that the insurgents pay for their crimes through his state's local judicial system,"[2]:292 "claiming" the prisoners "to be dealt with according to the laws of Virginia".[21][22]

In short, Brown and his men did not face federal charges. There were no federal court facilities nearby, and transporting the injured Brown and the other defendants to a federal courthouse—Staunton, Virginia, was mentioned, as well as Richmond or Washington D.C.—and maintaining them there would have been difficult and expensive. And what would this gain? Murder was not a federal crime, and a federal indictment for treason or fomenting slave insurrection would have caused a political crisis (because so many abolitionists would have denounced it). Under Virginia law, fomenting a slave insurrection was clearly and unequivocally a crime. And the defendants could be tried where they were, in Charles Town. Wise claimed that he had protected Brown from lynching.

The trial, then, took place in the county courthouse in Charles Town, not to be confused with today's capital, Charleston, West Virginia. Charles Town is the county seat of Jefferson County, about 7 miles (11 km) west of Harpers Ferry. The judge was Richard Parker, of Winchester.

Military presence to prevent rescue

Governor Wise wrote President Buchanan on November 25:

Sir: I have information from various quarters, upon which I rely, that a conspiracy, of formidable extent in means and numbers, is formed in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and other states, to rescue John Brown and his associates, prisoners at Charlestown, Virginia. The information is specific enough to be reliable. It convinces me that an attempt will be made to rescue the prisoners; and if tfiat fails, to seize citizens of this state as hostages and victims in case of execution.[23]

Wise never set down in writing what the information he received consistrd of. We have one report of a boy of 17 who, to annoy the Virginians, sent a letter to John Brown telling him:

to be of good cheer, that a company of men was being organized In our place to assist in his rescue, etc., which was all pure fiction. This letter. if signed at all, which I do I not remember, was signed with some fictitious name, and was addressed to John Brown, Charlestown Jail, Virginia. I well knew, or at least thought, that the letter would not reach Brown, but would fall Into the hands of the Virginia authorities, and chuckled over the Idea that It would create some excitement, and if the old carpet-bag Mr. Hunter refers to is ever recovered, no doubt my letter, postmarked Salem, O., will be found with the others he mentions.[24]

Wise sent "detectives" to Harpers Ferry, charging Andrew Hunter, Wise's personal lawyer and his representative in Charles Town, to use them to investigate rescue efforts from Ohio. "I sent one to Oberlin, who joined the party there, slept one night in the same bed as John Brown, Jr., and reported to me their doings out and out," said Hunter. No action was taken on these Ohio rescue plans, although Hunter had "troops" moved to block entry into Virginia. Action was also planned in Kentucky.[25]

A large armed force was stationed at Charles Town to prevent attempts at rescue.[18]:295 Brown was brought into court "accompanied by a body of armed men. Cannon were stationed in front of the court house, and an armed guard were [sic] patrolling round the jail."[18]:301 "The Governor [kept] the state troops constantly on guard. so that from the time Brown and his men were put in jail until after his execution, Charlestown [sic] had much the appearance of a military camp."[26]:9 Until the day of his execution Brown expected to be rescued by his partisans, although he denied repeatedly that he wanted to be rescued.[26]:8–9 So far as is known, no action was taken on any rescue plans.[27]:44, 62 n. 18

Charles Town was described thus by reporters there at the time:

The village, turn where you will, presents every appearance of a besieged town, what with cannon in the streets, troops marching and parading, sentries pacing to and fro, orderlies hurrying hither and thither, public buildings, offices, chuches, and private houses turned into barracks, and around them all the cooking, cleaning of accoutrements, and the thousand other accessories of soldiers' quarters.[28]

The Court being in recess:

The Court room, where so lately Brown and his associates were tried, is now a barrack room for one of the Richmond companies. Bedticks filled with straw were piled up on one side, arms stacked in another place, belts and cloaks hung up wherever a nail or a hook could be got into the wall, and the Judge's arm chair was occupied by a young volunteer, who was enjoying his after-breakfast pipe.[29]

Grand jury

Brown faced a grand jury on Tuesday, October 25, 1859, just eight days after his capture in the armory. The grand jury was also considering the other prisoners to be tried with Brown: Aaron Stephens, Edwin Coppie, Shields Green, and John Copeland. The courtroom was so crowded with spectators that there was not even standing room.[26]:9 At 5 PM the grand jury reported they had not yet finished questioning of witnesses, and the hearing was adjourned until the next day. On October 26 the grand jury returned a true bill of indictment against Brown and the other defendants, charging them with:

- "Conspiring with negroes to produce insurrection",

- Treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

- Murder.[18]:298[30]

Counsel

The next question was what legal counsel Brown was to have. The Court assigned two "Virginians and pro-slavery men", John Faulkner and Lawson Botts, as counsel for him and the other accused. Brown did not accept them; he told the judge that he had sent for counsel, "who have not had time to reach here".[18]:293

I did not ask for any quarter at the time I was taken. I did not ask to have my life spared. The Governor of the State of Virginia tendered me his assurance that I should have a fair trial, but under no circumstances whatever will I be able to attend to a trial. If you seek my blood, you can have it at any moment without the mockery of a trial. I have had no counsel. I have not been able to advise with any one. I know nothing about the feelings of my fellow-prisoners, and am utterly unable to attend in any way to my own defence. My memory don't serve me. My health is insufficient although improving. There are mitigating circumstances, if a fair trial is to be allowed us, that I would urge in our favor, but if we are to be forced, with the mere form of a trial[,] to execution, you might spare yourselves that trouble. I am ready for my fate. I do not ask a trial. I beg for no mockery of a trial—so insult nothing but that which conscience gives or cowardice would drive you to practice. I ask to be excused from the mockery of a trial. I do not know what the design of this examination is[.] I do not know what is to be the benefit of it to the Commonwealth? I have now little to ask other than that I be not foolishly insulted[,] as the cowardly barbarous insult, those who fall into their power.[31][32]

Brown asked for "a delay of two or three days" for his counsel to arrive.[18]:302 The judge turned down Brown's request: "the expectation of other counsel...did not constitute a sufficient cause for delay, as there was no certainty about their coming. ...The brief period remaining before the close of the term of the Court rendered it necessary to proceed as expeditiously as practicable, and to be cautious about granting delays."[18]:303

The judge's refusal to postpone the trial even one day to allow Brown's counsel to arrive, or when it did arrive, to allow it to read the indictment and the testimony given so far (see below), and that Brown was being tried when he was too wounded to stand, much less "attend to his own defense", contributed to Brown's transformation into a martyr.[27]

The remainder of October 26 was used to choose jurors. Also on the 26th, abolitionist Lydia Maria Child sent Wise a letter to deliver to Brown, and asked to be permitted to nurse him.[33] Wise responded that she was free to go to Charles Town, that he had forwarded her letter there, but only the court could allow her access.[34][35][36]:24–25 Child's letter did reach Brown, who replied that he was recovering and did not need nursing. (In fact he didn't want nursing; it felt unmanly and made him uncomfortable.) He suggested instead that she raise funds for the support of his wife and the wives and children of his dead sons.[37] Child sold her piano to raise funds for Brown's family.[38] After publishing it in newspapers, where it was widely read, she also published, to raise money, her correspondence with and relating to Brown.[39] It sold over 300,000 copies,[27]:58 and contributed to the sanctification of Brown.

Trial

On Thursday, October 27, the trial proper began. Brown stated that he did not wish to use an insanity defense, as had been proposed by relatives and friends.[18]:309[26]:12[40]:350–351 A court-appointed lawyer said that a Virginia court could only try Brown for acts committed in Virginia, not in Maryland or on federal property (the arsenal). State counsel denied this was relevant.

Brown, having received by telegraph news from a lawyer in Ohio, asked for a delay of one day; this was denied. The state attorney said that Brown's real motive was "to give to his friends the time and opportunity to organize a rescue."[18]:310

On Friday, October 28, George Henry Hoyt, a young but prominent Boston lawyer, arrived as counsel.[18]:317 One report says that Hoyt was a volunteer, but another that Hoyt was hired to defend Brown by John W. Le Barnes, one of the abolitionists who had given money to Brown in the past.

On that day Brown was described as "walking feebly" from thejail to thecourthouse, where he lay down on the cot.[41]

Prosecution

The prosecuting attorney for Jefferson County was Charles R. Harding, "whose daily occupations [drinking] are not of the nature to fit for the management of an important case". He was not on the same level as the defense attorneys. He agreed, unhappily, to be replaced for these cases, as Wise wanted, by Wise's personal attorney, Andrew Hunter.[42] A Northern newspaper described Hunter as a "furious advocate of slavery".[43]

The prosecuting attorney, then, was Hunter, whose office was in Charles Town. He wrote the indictment.

It is a novel sight, however, to observe the lawyers' offices, as well as the public buildings, turned into barracks and guard-rooms, and the floors covered with straw for bedding, knapsacks, baggage, &c., of the soldiers. The outer office of Andrew Hunter, Esq., adjoining the courthouse, is used as a kitchen for certain companies. A huge cooking stove, rounds of beef resting against well-filled shelves of law books, cooks actively engaged &c., imparted to his office entrance quite a singular appearance.[44]

The central prosecution witness in the trial was Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington, who had been kidnapped out of his home and held hostage near the Federal Armory. His slaves were militarily "impressed" (conscripted) by Brown, but they took no active part in the insurrection. Other local witnesses testified to the seizure of the federal armory, the appearance of Virginia militia groups, and shootings on the railroad bridge. Other evidence described the U.S. Marines' raid on the fire engine house where Brown and his men were barricaded. U.S. Army Colonel Robert E. Lee and cavalry officer J. E. B. Stuart led the Marine raid, and it freed the hostages and ended the standoff. Lee did not appear at the trial to testify, but instead filed an affidavit to the court with his account of the Marines raid.

The manuscript evidence was of particular interest to the judge and jury. Many documents were found on the Maryland farm rented by John Brown under the alias Isaac Smith. These included hundreds of undistributed copies of a previously unknown Provisional Constitution for an anti-slavery gocverbment. These documents clinched the treason and pre-meditated murder charges against Brown.

The prosecution concluded its examination of witnesses. The defense called witnesses, but they did not appear as subpoenas had not been served on them. Mr. Hoyt said that other counsel for Brown would arrive that evening. Both court-appointed attorneys then resigned, and the trial was adjourned until the next day.[18]:323

Defense

The trial resumed on Saturday, October 29. A lawyer, Samuel Chilton, arrived from Washington, and asked for a few hours to read the indictment and the testimony so far given; this was denied.[18]:325–326 The defense called six witnesses.[18]:326–328

The defense claimed that the Harpers Ferry Federal Armory was not on Virginia property, but since the murdered townspeople had died in the streets outside the perimeter of the Federal facility, this carried little weight with the jury. John Brown's lack of official citizenship in Virginia was presented as a defense against treason against the State. Judge Parker dispatched this claim by reference to "rights and responsibilities" and the overlapping citizenship requirements between the Federal union and the various states. John Brown, an American citizen, could be found guilty of treason against Virginia on the basis of his temporary residence there during the days of the insurrection.

Three other substantive defense tactics failed. One claimed that since the insurrection was aimed at the U.S. government it could not be proved treason against Virginia. Since Brown and his men had fired upon Virginia troops and police, this point was mooted. His lawyers also said that since no slaves had joined the insurrection, the charge of leading a slave insurrection should be thrown out. The jury apparently did not favor this claim, either.

Extenuating circumstances were claimed by the defense when they stressed that Colonel Washington and the other hostages were not harmed and were in fact protected by Brown during the siege. This claim was not persuasive as Colonel Washington testified that he had seen men die of gunshot wounds and had been confined for days.

A dissenting news story reported Washington having testified on the 28th:

The evidence on Friday. proving that Brown had treated his prisoners kindly, and had exercised great forbearance towards the citizens, forbidding his men to fire upon [illegible] unarmed, or into houses where women and children might be sheltered, had greatly mollified the public resentment. People began to think he was not such a terrible monster after all, and some expressions of pity for his condition were even heard; but when, upon finding that his witnesses were absent, Brown rose and denounced his counsel, declaring he had no confidence in them, the indignation of the citizens scarcely knew bounds.[45]

The final plea by the defense team for mercy concerned the circumstances surrounding the death of two of John Brown's men, who were apparently fired upon and killed by the Virginia militia while under a flag of truce. The armed community surrounding the Federal Arsenal did not hold their fire when Brown's men emerged to parley. This incident is noticeable upon a close reading of the published testimony, but is generally neglected in more popular accounts. If the rebels under a flag of truce were deliberately fired upon, it does not appear to have been a major issue to the judge and jury.

The defense's closing argument was given by Hiram Griswold, a lawyer from Cleveland, Ohio, who arrived on October 31. Griswold was well-known as an abolitionist; he had helped fugitive slaves, and was representing Brown pro bono. In contrast, Chilton was no abolitionist, and only became involved after supporters of Brown promised to pay a very high fee, $1,000 (equivalent to $28,456 in 2019).[46]:1791

Brown, while making various suggestions to his attorneys, was frustrated because under Virginia law, defendants were not allowed to testify, the assumption being that they had reason not to tell the truth.[46]:1792

Verdict

The prosecution began its closing argument on Friday, concluding on Monday, October 31.[18]:333 The jury retired to consider its verdict.[18]:334–336

The jury deliberated for only 45 minutes. When it returned, according to the report in the New York Herald, "the only calm and unruffled countenance there" was that of Brown. When the jury reported that it found him guilty of all charges, "not the slightest sound was heard in the vast crowd".[47]

One of Brown's attorneys made "a motion for an arrest of judgment", but it was not argued. "Counsel on both sides being too much exhausted to go on, the motion was ordered to stand over until tomorrow, and Brown was again removed unsentenced to prison" (actually to the Jefferson County jail).[47]

Speech to the court and sentence

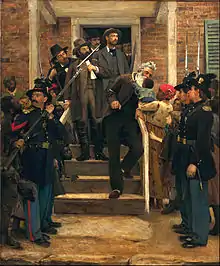

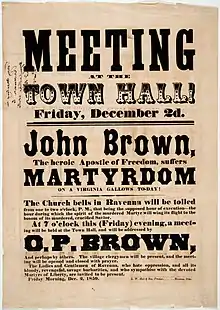

Brown's sentencing took place on November 2, 1859. As Virginia court procedure required, Brown was first asked to stand and say if there was reason sentence should not be passed upon him. He arose—he could now stand unassisted—and made what his first biographer called "[his] last speech".[18]:340 He said his only goal was to free slaves, not start a revolt, that it was God's work, that if he had been helping the rich instead of the poor he would not be in court, and that the criminal trial had been more fair than he expected. According to Ralph Waldo Emerson, this speech's only equal in American oratory is the Gettysburg Address.[48][36]:36 It was reproduced in full in at least 52 American newspapers, making the front page of the New York Times, the Richmond Dispatch, and several other papers.[49] Wm. Lloyd Garrison printed it on a broadside and had it for sale in The Liberator's office (reproduced in Gallery, below).

After Brown completed his speech, the entire courtroom sat in silence. According to one journalist news source: "The only demonstration made was by the clapping of the hands [applauding] of one man in the crowd, who is not a resident of Jefferson County. This was promptly suppressed, and much regret is expressed by the citzens at its occurrence."[50] The judge then sentenced Brown to death by hanging to take place in 30 days on December 2.[18]:340–342 Brown received his death sentence with composure.

November 2–December 2

Under Virginia law a month had to separate the sentence of death and its execution. Governor Wise resisted pressures to move up Brown's execution because, he said, he did not want anyone saying that Brown's rights had not been fully respected. The delay meant that the issue grew further; Brown's raid, trial, visitors, correspondence, upcoming execution, and Wise's role in making it happen were reported on constantly in newspapers, both local and national.[51]

An appeal to the Virginia Court of Appeals (a petition for a Writ of Error) was not successful.[52][53]:248 Hoyt, attorney for Brown and Edwin Coppock, returning to Charles Town to gather documents for their appeals, was advised to leave Charles Town for his own safety.[54]

The question of clemency

Many things that Governor Wise did augmented rather than reduced tensions: by insisting he be tried in Virginia, and by turning Charles Town into an armed camp, full of state militia units. "At every juncture he chose to escalate rather than pacify sectional animosity."[36]:27

Wise received many communications—thousands[53]:250—urging him to mitigate Brown's sentence. For example, New York City Mayor Fernando Wood, who would seriously propose that New York City secede from the Union so as to continue the cotton trade with the Confederacy, and who strongly opposed the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery, wrote Wise on November 2. He advocated sending Brown to prison instead of executing him, saying that it was in the South's interest to do so; it would benefit the South more to behave magnanimously toward a fanatic, with whom there is sympathy, than to execute him.

Wise replied that in his view Brown should be hung, and he regretted not having gotten to Harpers Ferry fast enough to declare martial law and execute the rebels through court-martial. Brown's trial was fair and "it was impossible not to convict him." As Governor, he had nothing to do with Brown's death sentence; he did not have to sign a death warrant. His only possible involvement was from his power to pardon, and he had received "petitions, prayers, threats from almost every Free State in the Union," warning that Brown's execution would turn him into a martyr. But Wise stated that it would not be wise to "spare a murderer, a robber, a traitor," because of "public sentiment elsewhere".[55] Public sentiment in Virginia clearly wanted Brown executed. Wise was spoken of as a possible presidential candidate,[53]:206 and a pardon or reprieve would have ended his political career.

Brown's correspondence

During the month between his conviction and his execution, Brown wrote over 100 letters, most of which, and a few to him, were immediately collected and published.[18]:344–372[56] Many appeared in newspapers. He had previously been prevented by the Court from "making a full statement of his motives and intentions through the press", as he desired; the Court had "refused all access to reporters".[18]:295 Now that he had been convicted and sentenced, there were no more restrictions on visitors, and Brown, relishing the publicity his anti-slavery views received, talked to reporters or anyone else that wanted to see him.

He states that he welcomes every one, and that he is preaching, even in jail, with great effect, upon the enormities of slavery.[18]:374

He wrote to his wife that he had received so many "kind and encouraging letters" that he could not possibly reply to them all.[57] "I do not think that I ever enjoyed life better than since my confinement here," he wrote on November 24.[58]:600 "I certainly think I was never more cheerful in my life."[36]:18 "My mind is very tranquil, I may say joyous."[59] | On November 28, Brown wrote the following to an Ohio friend, Daniel R. Tilden:

I have enjoyed remarkable cheerfulness and composure of mind since my confinement; and it is a great comfort to feel assured that I am permitted to die (for a cause)[,] not merely to pay the debt of nature (as all must). I feel myself to be most unworthy of so great distinction. The particular matter of dying assigned to me, gives me but very little uneasyness. I wish I had the time and the ability to give you (my dear friend) some little idea of what is daily and I might almost say hourly, passing within my prison walls; and could my friends but witness only a few of those scenes just as they occur, I think they would feel very well reconciled to my being here just what I am and just as I am. My whole life before had not afforded me one-half the opportunity to plead for the right. In this also I find much to reconcile me to both my present condition and my immediate prospect. I may be very insane (and I am so, if insane at all). But if that be so, insanity is like a very pleasant dream to me. I am not in the least degree conscious of my ravings; of my fears; or of any terrible visions whatever; but fancy myself entirely composed; and that my sleep, in particular, is as sweet as that of a healthy, joyous little infant. I pray God that he will grant me a continuance of the same calm, but delightful, dream, until I come to know of those realities which “eyes have not seen, and which ears have not heard” (1 Corinthians 2:9). I have scarce realized that I am in prison, or in irons, at all. I certainly think I was never more cheerful in my life.[60]

Contemporary assessments

Northerners commemorated the trial and coming execution with public prayers, church services, marches, and meetings.[27]:45 By December 2, "the entire nation" was fixated on Brown.[61]

The New York Independent said the following of him during this month:

The brave old man who lies in prison at Charlestown, Virginia, awaiting the day of his execution, is teaching this nation lessons of heroism, faith and duty, which will awaken its sluggish moral sense, and the almost forgotten memories of the heroes of the Revolution.[62]

In contrast, the Richmond Dispatch called him a "scoundrel", adding that he was "a cold-blooded, midnight murderer, with not a particle of humanity or generosity belonging to his character." "The recent events at Harper's Ferry have very much roused the military spirit among us."[63]

Visit from Henry Clay Pate

His visitors included his pro-slavery enemy from Kansas Henry Clay Pate, who came 175 miles (282 km) from his home in Petersburg to Charles Town to see Brown.[64] They prepared a statement, witnessed by Capt. John Avis and two others, about events at the Battle of Black Jack.[65]:30–31, 37–39

His will

On December 1, in the presence of his wife, at his request Judge Andrew Hunter wrote Brown's will, witnessed by Hunter and the jailor Captain John Avis.[66][58]:617 He distributed his few possessions—his surveyor's implements, his silver watch, the family Bible—to his surviving children. Bibles were to be purchased for each of his children and grandchildren.[67]:108[18]:367–368

In his correspondence Brown mentioned several times how well he was treated by Avis, who was also in charge of Brown's execution and the one who put the noose around his neck.[58]:622 Avis was described by a visitor to the jail as Brown's friend.[68] Brown's wife had arrived on November 30,[69]:549 and the couple had their last dinner with Avis's family in their apartment at the jail. That is where they last saw each other.[8][9][10][11][12] According to Andrew Hunter,

The only time that I witnessed any exhibition of temper on the part of Brown was in the interview we had about Mrs. Brown. Gen. Talliaferro told me that his instructions were to send her back [to Harpers Ferry] that night. He showed a good deal of temper, as he wanted her to remain all night. It was determined otherwise, and when I explained to Brown fully the reason of it, he again acquiesced and took leave of her after she had eaten her supper with the family of the jailer, Avis. She was treated throughout with the most marked respect.[51]

It was Avis who asked Brown for an autograph, receiving the slip of paper with the famous last words quoted below. His "humane treatment of Brown called forth the most severe criticisms from the Virginians."[70]:329

Execution

Brown was the first person executed for treason in the history of the United States. He was hanged on December 2, 1859, at about 11:15 AM,[71] in a vacant field several blocks away from the Jefferson County jail.

There is everywhere discernable here a vague dread of some fearful expression of sympathy with Brown on the fateful Friday.[72]

[I]t is strange and sad, assuredly, that in one State of the American Union, it should be found necessary to surround with a guard of five thousand soldiers, the scaffold of a condemned man, in honor of whom, in other States of the same Union, the bells of churches will be tolling, and the voices of Christian congregations lifted in prayer, at the same hour of his death.[73]

Spectators

About 2,000 "excursionists" intended to attend the execution, but the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad refused to transport them, and Governor Wise shut down the Winchester and Potomac Railroad for other than military use. Threatening to invoke martial law, Wise asked all citizens to remain at home,[72] as did the mayor of Charles Town (see below). Thomas Jackson (the future Stonewall Jackson) was present, as was Robert E. Lee and 2,000 Federal troops and Virginia militia.[74] Militia had been stationed in Charles Town continuously from the arrest until the execution, to prevent a much-feared armed rescue of Brown.[75][26]:24[76]

Military orders for the day of execution had 14 points.[77]

As further protection, "a field-piece loaded with grape and canister had been planted directly in front of and aimed at the scaffold, so as to blow poor Brown's body to smithereens in the event of attempted rescue."[78] "The outer line of military will be nearly a mile (1.4 km) from the scaffold, and the inner line so distant that not a word John Brown may speak can be heard."[74]

Gov. Wise...gives as the reason for this exclusion of all save the military, that in the event of an attempted rescue an order to fire upon the prisoner will be given, and that those within the line, especially those sufficiently near the gallows to hear what Brown may say, would inevitably share his fate.[74]

Among the spectators were the poet Walt Whitman[79] and the actor John Wilkes Booth, the latter of whom was such a white supremacist that in five years he would assassinate President Lincoln, after Lincoln supported giving Blacks the vote, which Booth called "nigger citizenship". He had read in a newspaper about the upcoming execution of Brown, whom he called "the grandest character of this century."[36]:185 n. 40 He was so interested in seeing it that he abandoned rehearsals at the Richmond Theater and travelled to Charles Town specifically for this purpose. So as to gain access that the public would not have, he donned for one day a borrowed uniform of the Richmond Grays,[36]:30 a volunteer militia of 1,500 men traveling to Charles Town for Brown's hanging, to guard against a possible attempt to rescue Brown from the gallows by force.[80] When Brown's collaborators Shields Green and John Copeland were hung two weeks later, on December 16, there were no restrictions, and 1,600 spectators came to Charles Town "to witness the last act of the Harpers Ferry tragedy".[81]

The gallows

According to legend, Brown kissed a black baby when leaving the jail en route to the gallows. Several men who were present specically deny it. For example, Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter: "That whole story about his kissing a negro child as he went out of the jail is utterly and absolutely false from beginning to end. Nothing of the kind occurred—nothing of the sort could have occurred. He was surrounded by soldiers and no negro could get access to him."[82][83]:446[84]

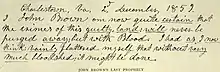

On the short trip from the jail to the gallows, during which he sat on his coffin in a furniture wagon,[85] Brown was protected on both sides by lines of troops, to prevent an armed rescue. As Governor Wise did not want Brown making another speech, after leaving the jail and on the gallows, spectators and reporters were kept far enough away that Brown could not have been heard.[36]:30 His last known words, aside from trivial remarks on the way to and at the gallows, are those on a note, passed to his kind jailor, Avis, who asked for an autograph:

Charlestown, Va. 2nd December, 1859. I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.

He gave a similar, even stronger form of the same statement to jailer Hiram O'Bannon: "I am now convinced that the great iniquity which hangs over this country cannot be purged without immense bloodshed. When I first came to this State I thought differently, but am now convinced that I was mistaken."[46]

On his way to the gallows he remarked to the Sheriff on the beauty of the country and the excellence of the soil. "This is the first time I have had the pleasure of seeing it."[46]

Ten doctors, one after another, all checked his pulse after the hanging, to be sure he was dead. The rope, specially made for the execution out of South Carolina cotton,[74] was cut up into pieces and distributed "to those that were anxious to have it". Others took pieces of the gallows, or a lock of his hair.[46]

Brown wanted his body and those of his sons burned, and then "urned", but that was not allowed in Virginia, the Sheriff said, and Mrs. Brown did not want it either.[86] Also, she did not feel up to identifying the partially decomposed body of Oliver, dead for over a month.[46] She rejected the repeated suggestion of Wendell Phillips, Lydia Maria Child, and others that John be buried "with impressive funeral solemnities" in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with the erection of a monument. Also she rejected proposals to pack his body in ice, with the rope around his neck, and exhibit it in "all our principal cities and even the minor ones." Despite the "great propaganda value" of these proposed measures,[27]:47 she returned home with her husband's body. Church bells rang and crowds gathered as they proceeded up the Hudson from New York.[27]:48

John Brown was buried at the John Brown Farm State Historic Site, near Lake Placid, New York, where his "body lies a-mouldering", as the Battle Hymn of the Republic says.

Immediate aftermath

Brown's execution on December 2 was what most white Southerners wanted, but it gave them little relief from their panic. Northern-inspired revolt of their allegedly happy enslaved was the South's worst nightmare, and it was taken for granted that others would soon follow in Brown's footsteps.

Meetings

Across the North, the day Brown was hanged was treated as a day of national calamity: bells were rung, meetings held, speeches and sermons given, the flag flown at half-mast.[87]:1 "'The times that tried men's souls' have come again."[87]:3 Huge prayer meetings were held in Concord, New Bedford, and Plymouth, Massachusetts, and many other cities. Churches and temples were full of mourners. In New York City, "lectures, discourses, speeches and poems are delivered every night everywhere, by everybody, pro and con, on John Brown, on Osawatomie Brown, on Old Brown, on Captain Brown, and on The Hero of Harper's Ferry. ...Truly this old farmer has made such a stir as not all the statesmen, ...little giants, and professional agitators have been able to produce, and which they are much less able to quiet."[88]

In Boston, flags were at half-mast, and memorial services were held in the public schools.[89]

In Albany, New York, Brown received a slow 100-gun salute.[90] In Syracuse, New York, City Hall was "densely packed" with citizens, who listened to over three hours of speeches and contributed "a large amount of money" to aid his family. The City Hall bell was rung 63 times, "the strokes corresponding with Brown's age".[91][71] (Brown was 59.) In Philadelphia, December 2 was designated "Martyr Day".[92] National Hall had an overflow crowd of more than 4,000, listening to prayers by Rev. William Henry Furness and speeches by Lucretia Mott and Mary Green.[93] In Cleveland there was a crowd of 5,000,[94] the Melodeon was draped in mourning. Across a main street was a banner with the quote: "I do not think I can better honor the cause I love than to die for it". Some businesses closed; in Akron, court adjourned.[95]

In Port-au-Prince, Haiti, there were three days of mourning, all flags were at half-mast, and houses and the cathedral were draped in black. They raised $2,240 (equivalent to $63,740 in 2019) to assist his widow Mary.[96] Avenue John Brown is the only major street anywhere in the world named for Brown. There is also a avoenue named for Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner.

Publications

Newspapers and magazines had whole sections on the episode. A poster (broadside) was made of Brown's last speech (see left). As there was as yet no process to print a photograph, a lithographed [engraved] reproduction of his last photograph and his signature were offered for sale for $1, to benefit the Brown family.[97]

Pamphlets started to appear as soon as Brown was sentenced, before his execution.[98][99][100] There were more just after his execution.[87][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108]

In December two books on Brown (by De Witt and Pate) were published.[109][65] A third, by Thomas Drew, was copyrighted in December,[110] although it appeared in 1860; De Witt almost immediately issued a 2nd edition with additional material.[111]

Noticing with what eager desire everything relating to the affair was sought by all classes of people, and the especial interest that was manifested in every circumstance that related personally to "The Hero of Harper's Ferry," [Drew] has sought to combine in these pages every fact and incident relating to the event, which the friends and admirers of the man would wish to preserve, as mementoes of the simplicity of his character, the nobility of his purposes, the disinterestedness of his motives, the sublime heroism of his deeds, and the remarkable piety by which he was governed and sustained.[110]:Preface

.jpg.webp)

It is no coincidence that the preface of the fourth, by the family's preferred biographer, James Redpath, is dated December 25, 1859, as Brown was sometimes seen, and saw himself, as Christ, or Moses leading the Israelites out of slavery. On the title page it has a version of the seal of Virginia, with its motto, "Sic semper tyrannis" ('Thus always to tyrants'), exclamation point added. As explained on the day of Brown's execution by abolitionist Wendell Phillips, to whom, along with Thoreau and the young Emerson, the volume is dedicated:

It is a mistake to call him an insurrectionist. He opposed the authority of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The Commonwealth of Virginia!—there is no such thing. There is no civil society, no government; nor can such exist except on the basis of impartial equal submission of its citizens—by a performance of the duty of rendering justice between God and man. The government that refuses this is none but a pirate ship. Virginia herself is to-day only a chronic insurrection. I mean exactly what I say—I consider well my words—and she is a pirate ship. John Brown sails with letters of marque from God and Justice against every pirate he meets. He has twice as much right to hang Governor Wise as Governor Wise has to hang him.[112]

At least 36,000 copies were sold of it,[18] 10,000 ordered in advance of its release.[113]

A 3-act play, Ossawatomie Brown; or, The Insurrection at Harper's Ferry, was first performed in New York at the Bowery Theater on December 16, 1859.[114] A Congressional inquest was held, multiple reports from participants and observers were published. The internal telegrams of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad were published.[115] Posters were printed. The literature on Brown and his raid exceeds in quantity that on some American presidents.

According to the New York Independent,

A fissure has suddenly opened at the very foundation of the peculiar institution of the South [slavery], and has disclosed the fact that that institution rests upon a thin crust of lava, which at any moment may yawn asunder and give place to a devouring fire. It is not what John Brown has done or failed to do, but the fearful possibilities that his crazy emeute [commotion, disturbance] has opened to view, which have inspired the South with a terror of coming evil. Foolhardy as was Brown's exploit, regarded merely as a military invasion for the rescue of the oppressed, unjustifiable as it was upon the principles of Christian ethics, yet this singular devotion of an old man to the cause of human freedom, his heroic contempt of his own life, blending with a sacred regard for the lives and property of others, except where these should stand in the way of the deliverance of the oppressed[,] are gradually pervading the public mind with a tone of admiration even for a misguided philanthropy, and startling the South with the idea that a philanthropy which will peril life for its object, is more to be feared than despised.[116]

.jpg.webp)

Subsequently he was eclipsed by the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, but from 1859 to 1865 he was the most famous American. In the North, his self-sacrifice showed by example how important fighting the sin of slavery was. For the South, he was what he had been in pro-slavery Kansas: the devil stirring up the hornet's nest, a traitor to the Constitution, which allegedly protected chattel slavery, and a murderer.

Reactions by Blacks

The barns of all the members of the jury that convicted Brown were burned by slaves. On November 2, 1859, the day of his hanging, "the farm of a ruthless slaveholder killed at Harper's Ferry was burned, and his livestock poisoned by slaves. Slaves in Maryland stopped a westbound train, carrying the rebellion into a different county, and five were arrested after trying to organize a horse-and-carriage 'stampede' to freedom." There was a "mass movement of self-liberation" among the slaves of Jefferson County.[117]:275 Barns were burned in Queen Anne's County, Maryland, and letters threatened further violence.[118]

Reenactment

The trial was reenacted in 2019 by students from Shenandoah University. A version will be available at Shenandoah Valley Civil War Museum, in Winchester, Virginia.[119]

Gallery

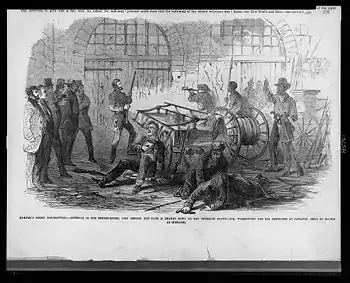

Interior of the engine house at the armory, just before the door is broken down. Note hostages on the left.

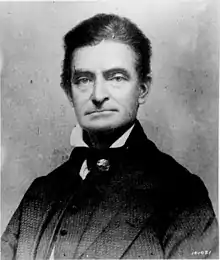

Interior of the engine house at the armory, just before the door is broken down. Note hostages on the left. John Brown at his arraignment before a grand jury, drawing dated 1899

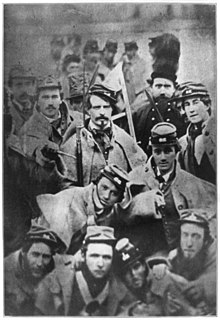

John Brown at his arraignment before a grand jury, drawing dated 1899 John Brown at his trial, unable to stand or sit

John Brown at his trial, unable to stand or sit A warning to citizens of Jefferson County, Virginia, and vicinity to stay home and not attend John Brown's execution.

A warning to citizens of Jefferson County, Virginia, and vicinity to stay home and not attend John Brown's execution. Broadside from mayor of Charles Town, Virginia, warning citizens to remain in their houses.

Broadside from mayor of Charles Town, Virginia, warning citizens to remain in their houses. John Brown's last words, given to the jailor, who requested an autograph. From an albumen print; location of the original is unknown.

John Brown's last words, given to the jailor, who requested an autograph. From an albumen print; location of the original is unknown._LCCN99614097.jpg.webp) John Brown riding on his coffin to the place of execution.

John Brown riding on his coffin to the place of execution. John Brown on his way to the gallows. Note soldiers on each side of wagon transporting Brown, to prevent an armed rescue.

John Brown on his way to the gallows. Note soldiers on each side of wagon transporting Brown, to prevent an armed rescue. Brown ascending the scaffold preparatory to being hanged. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, December 17, 1859

Brown ascending the scaffold preparatory to being hanged. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, December 17, 1859 John Brown hanging. Note spectators at lower right. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, December 10, 1859.

John Brown hanging. Note spectators at lower right. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, December 10, 1859.

See also

References

- WGBH (1998). "The raid on Harpers Ferry". Africans in America. PBS. Archived from the original on 2017-09-09. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- McGlone, Robert E. "Retrying John Brown: Was Virginia Justice "Fair"?". Reviews in American History. 3 (2). pp. 292–298. Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-12-13 – via Project MUSE.

- "The Insurrection in Virginia". New York Herald. October 24, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- John Brown's Interview in the Charlestown (or Charles Town) Prison, famous-trials.com, October 18, 1859, archived from the original on June 16, 2019, retrieved August 18, 2020

- Our own reporter (19 October 1859). "The late rebellion". The Daily Exchange. Baltimore, Maryland. p. 1. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "News, rumors and gossip from Harper's Ferry. From our special reporter". New York Herald. November 1, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "The Executions at Charlestown. Scenes previous to the execution. The military display. Religious services in the cells. The attempted escape. Last interview of the conspirators. Scenes at the gallows. &c., &c., &c". Daily Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia). December 19, 1859. p. 1 – via VirginiaChronicle.

- "Visit of Mrs. Brown to her Husband". Boston Cultivator. December 10, 1859. p. 402.

- "Mrs. Brown's visit to her husband". Burlington Free Press. Burlington, Vermont. December 12, 1859. p. 2. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020 – via newspapers.com. Reprinted from the The Independent (New York City).

- "The tragedy in Virginia. Arrival of Mrs. Brown". The Liberator. December 9, 1859. p. 195. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020 – via newspapers.com. Reprinted from the New York Tribune

- "Affecting interview with his wife". Mount Carmel Register (Mount Carmel, Illinois). December 9, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020 – via newspapers.com. "Telegraphed expressly for the Cincinnati Gazette."

- "Interview of Brown with his Wife in Jail". New York Herald. December 2, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- John T[homas] Allstadt (December 1909). "John Brown's raid fifty years ago". The Magazine of History with notes and queries. 10 (6): 309–342, at page 324.

- "Our Illustrations". Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. November 12, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020 – via AccessibleArchives.com.

- "John Brown's death". Mohave County Miner (Kingman, Arizona). July 14, 1888. p. 1 – via Chronicling America.

- Stutler, Boyd B. (February 1955). "An Eyewitness Describes The Hanging Of John Brown". American Heritage. 6 (2) – via Chronicling America.

- "Editor's Table". Yale Literary Magazine. 25 (3): 230–238, at pp. 234–237. December 1859. Archived from the original on 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- Redpath, James (1860). The Public Life of Captain John Brown, by James Redpath, with an auto-biography of his childhood and youth. Boston: Thayer & Eldridge.

- "Operation of state and national troops". Anti-Slavery Bugle (Lisbon, Ohio). October 29, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "Harper's Ferry Insurrection—The thing in a nutshell". Fremont Weekly Journal (Fremont, Ohio). October 28, 1859. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "Fourth Dispatch". Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia). October 19, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "Latest by telegraph". The Daily Exchange (Baltimore, Maryland). 19 October 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- Wise, Henry A. (1859). "Governor Wise's Letter to President Buchanan". Documents relating to the Harpers Ferry Invasion. "Appendix to Message 1 [unidentified]". p. 51.

- Baird, R. K. (April 22, 1888). "An Ohio Man's Story—The Funeral over Coppic's body". St. Louis Globe-Democrat (St. Louis, Missouri). p. 32 – via newspapers.com.

- Hunter, Andrew (September 18, 1887). "John Brown's Raid. Interesting Reminiscences Written by the Lawyer Wbo Prosecuted Him.—Incidents of His Trlal—HIs Conviotlon, Sentence and Execution. —His Purposes as He Declared Them.—The Effect of the Raid on Southern Sentiment". St. Joseph Gazette-Herald (St. Joseph, Missouri). p. 9 – via newspapers.com.

- Caskie, George E. (1909). Trial of John Brown. Paper read by Hon. George E. Caskie, of Lynchburg before the Virginia State Bar Association, at Homestead Hotel, Hot Springs, Virginia, August 10th, 11th and 12th, 1909. Richmond, Virginia. Archived from the original on 2020-08-29. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- Finkleman, Paul (1995). "Manufacturing Martyrdom. The anti-Slavery Response to John Brown's raid". In Finkleman, Paul (ed.). His Soul Goes Marching On. Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. pp. 41–66, at p. 43. ISBN 0813915368.

- "John Brown's Invasion. Further interesting incidents of the execution". New-York Tribune. December 6, 1859. p. 6. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "Scenes in Charlestown. ...Troops in the Temple of Justice", New York Daily Herald, p. 1, December 3, 1859 – via newspapers.com

- "The Bill of Indictment found against the prisoners". New York Daily Herald. October 30, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "The Harper's Ferry Trouble". Valley Spirit. Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. November 2, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "Trial of Brown". The Liberator. October 28, 1859. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- Child, L. Maria (1905), "Letter from Mrs. Child to John Brown", in Zittle, Hanna Minnie Weaver (ed.), A correct history of the John Brown invasion at Harper's Ferry, West Va., Oct. 17, 1859. Compiled by the late Capt. John H. Zittle, of Shepherdstown, W. Va., Who was an Eye-Witness to many of the occurrences, and edited and published by his widow, Hagerstown, Maryland, pp. 116–117

- Child, Lydia Maria; Wise, Henry A. (November 8, 1859). "Mrs. Child and the insurgent Brown". Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, Virginia). p. 1. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- "Extraordinary address of Wendell Phillips on the insurrection". New York Daily Herald. November 2, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- Nudelman, Franny (2004). John Brown's body: slavery, violence & the culture of war. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807828831.

- Brown, John (1897). Words of John Brown. Old South Leaflets, 84. Boston: Directors of the Old South Work. pp. 19–20. Archived from the original on 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- "For Sale—John Brown". National Anti-Slavery Standard. January 7, 1860. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020 – via accessiblearchives.com.

- Child, Lydia Maria (1860). Correspondence between Lydia Maria Child and Gov. Wise and Mrs. Mason of Virginia. Boston: American Anti-Slavery Society.

- Reynolds, David S. (2005). John Brown, Abolitionist. The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. Vintage Books. ISBN 0375726152.

- "The Harper's Ferry Invasion. Trial of John Brown". Detroit Free Press (Detroit, Michigan). October 29, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "Personal Portraits". Staunton Spectator. November 29, 1859. p. 1.

- "Those that fought with John Brown at Harper's Ferry". Indianapolis Recorder. February 27, 1937. p. 9.

- "Letters from Charlestown". Baltimore Sun. December 6, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "News, Rumors and Gossip from Harper's Ferry [pt. 2]". New York Daily Herald. November 1, 1859. p. 10 – via newspapers.com.

- "The Execution of Old John Brown. Full particulars of the prison and gallows scene. Old Brown's Will. He writes his own epitaph. Last interview with his wife and fellow-prisoners, &c. &c". Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois). December 5, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 27, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "The Harper's Ferry Tragedy. Conclusion of first day's proceedings". The Liberator. November 4, 1859. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo (April 19, 1865). "Remarks at the funeral services [for Abraham Lincoln] held in Concord, April 19, 1865". Centenary Edition. The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson. 11. Archived from the original on March 9, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- "The Trial at Charlestown". Richmond Dispatch. November 4, 1859. p. 1.

- "Virginia Rebellion. John Brown Sentenced to Death. His Address to the Court and Jury. Edward Coppie Found Guilty". New York Times. November 3, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- Hunter, Andrew (September 5, 1887). "John Brown's Raid. Recollections of Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter. The Capture, Trial, and Execution of Brown and His Party—Operatoons of His Enissaries—The Leader's Firmness and Coolness—Incidents of the Trial and Execution—Preparations to Prevent a Rescue". The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana). p. 6 – via newspapers.com.

- "No Writ of Error". Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, Virginia). November 22, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- Wise, Barton Haxall (1899). The life of Henry A. Wise of Virginia, 1806-1876. New York: Macmillan. p. 206.

- "The expulsion of Mr. Hoyt from Charleston". New-York Daily Tribune. November 17, 1859. p. 5 – via newspapers.com.

- "Another Leaf of History". New York Times. May 12, 1865. p. 5. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Brown, John (2015). DeCaro Jr., Louis (ed.). John Brown speaks : letters and statements from Charlestown. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442236707.

- Brown, John (November 26, 1859), Letter to Mary Brown, archived from the original on December 9, 2020, retrieved September 12, 2020

- Sanborn, Franklin B; Brown, John (1885). The Life and Letters of John Brown, Liberator of Kansas, and Martyr of Virginia. Boston: Roberts Brothers.

- Brown, John, My dear wife [letter], p. 53

- "Another letter from John Brown". New York Times. December 5, 1859. p. 8. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- Finkleman, Paul (1995). "Preface". In Finkleman, Paul (ed.). His Soul Goes Marching On. Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. pp. 3–9, at p. 8. ISBN 0813915368.

- Taft, S[tephen] H. (1872). A discourse on the chapter and death of John Brown (2nd ed.). Des Moines. p. 12.

- "To Arms! To Arms!". Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia). November 7, 1859. p. 2. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "Capt. Brown and Capt. Pate". Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, Virginia). November 29, 1859. p. 2. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Pate, Henry Clay (1859). John Brown. Published by the author. New York.

- Hunter, Andrew (September 5, 1887). "John Brown's Raid. Recollections of Prosecuting Attorney Andrew Hunter. The Capture, Trial, and Execution of Brown and His Party—Operatoons of His Enissaries—The Leader's Firmness and Coolness—Incidents of the Trial and Execution—Preparations to Prevent a Rescue". The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana). p. 6 – via newspapers.com.

- De Witt, Robert M. (1859). The Life, Trial and Execution of Captain John Brown, Known as "Old Brown of Ossawatomie," with a full account of the attempted insurrection at Harper's Ferry, Virginia. Compiled from official and authentic sources. Inducting Cooke's Confession, and all the Incidents of the Execution. New York: Robert M. De Witt.

- Russell, Thomas (December 24, 1880). "The Last Hours of John Brown". Republican Record (Fort Scott, Kansas). p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- Villard, Oswald Garrison (1910). John Brown, 1800-1859, a biography fifty years after. London: Constable.

- Chapin, Lou V. (1899). "The Last Days of Old John Brown". Overland Monthly. Second series, 33: 322–332. Archived from the original on 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- "News of the Day". New York Times. December 3, 1859. p. 4. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- "The Panic at Charlestown [sic]". New York Times. December 1, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- "John Brown's Execution". New York Times. December 2, 1859. p. 4. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- "Uncivilized". Berkshire County Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts). December 1, 1859. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "The great Virginia mare's nest. The plot to rescue John Brown—The revelations which called out the military". National Anti-Slavery Standard. December 3, 1859. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2020 – via accessiblearchives.com.

- Buchanan, James (May 12, 1865) [November 5, 1859]. "Letter of President Buchanan to Governor Wise". New York Times. p. 5. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- "The following orders were issued last night". Daily Exchange (Baltimore, Maryland). December 3, 1859. p. 2. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Olcott, Henry S. (1875), "How We Hung John Brown", in Brougham, John; Elderkin, John (eds.), Lotos Leaves, Boston: William F. Gill, pp. 233–249, at p. 244, archived from the original on 2020-12-09, retrieved 2020-10-05

- Taylor, Stephen J. (October 21, 2015), A Skeleton's Odyssey: The Forensic Mystery of Watson Brown, Hoosier State Chronicles, Indiana State Library, archived from the original on November 1, 2020, retrieved October 21, 2020

- Kauffman, American Brutus, p. 105.

- "John Brown's War. Another Panic in Virginia". Chicago Tribune. December 17, 1859. p. 4. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Hunter, Andrew (July 1897). John Brown's Raid. Publications of the Southern History Association. 1. pp. 165–195, at p. 174.

- Norris, J. E. (1890). History of the lower Shenandoah Valley counties of Frederick, Berkeley, Jefferson and Clarke, their early settlement and progress to the present time; geological features; a description of their historic and interesting localities; cities, towns and villages; portraits of some of the prominent men, and biographies of many of the representative citizens. Chicago: A. Warner & Co.

- "(Untitled)". The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts). January 6, 1860. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Taft, Stephen H. (1872). A discourse on the chapter and death of John Brown (2nd ed.). Des Moines, Iowa. p. 21.

- "Directions about the disposition of his body". National Era (Washington, D. C.). December 8, 1859. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- A tribute of respect, commemorative of the worth and sacrifice of John Brown, of Ossawatomie. It being a full Report of the Speeches made and the Resolutions adopted by the citizens of Cleveland, at a meeting held in the Melodeon, on the evening of the day on which John Brown was sacrificed by the Commonwealth of Virginia: together with a Sermon, commemorative of the same sad event. Cleveland, Ohio: Published for the benefit of the widows and families of the revolutionists of Harper's Ferry. 1859.

- J. S. (January 5, 1860). "More Light!". Lawrence Republican (Lawrence, Kansas). ("More light!" were the last words of Goethe). p. 2. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- John T[homas] Allstadt (December 1909). "John Brown's raid fifty years ago". The Magazine of History with notes and queries. 10 (6): 309–342, at page 341.

- Korda, Michael (2014). Clouds of Glory : The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee. An excerpt, "When Robert E. Lee Met John Brown and Saved the Union", was published in The Daily Beast. Harper. pp. xxxviii–xxxix. ISBN 978-0062116314.

- "'Brown' at Syracuse". National Era (Washington, D.C.). December 8, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- V. Chapman-Smith. "John Brown's Philadelphia" (PDF). Civil War History Consortium. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- "Prayers in Philadelphia". National Era (Washington, D.C.). December 8, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "The Execution of John Brown at Cleveland". Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia). December 5, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "In Memoriam. Exercises Commemorative of the Execution of John Brown". Cleveland Daily Leader (Cleveland, Ohio). December 3, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- Pamphile, Leon D. (Fall 2006). "The Haitian Response to the John Brown Tragedy". Journal of Haitian Studies. 12 (2): 135–142. JSTOR 41715333.

- "Portrait of John Brown". The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts). December 23, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- Cheever, George Barrell (1859). The Curse of God Against Political Atheism. With Some of the Lessons of the Tragedy at Harper's Ferry : a Discourse Delivered in the Church of the Puritans, New York, on Sabbath Evening, Nov. 6, 1859. Boston: Walker, Wise, & Co. Archived from the original on 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

- Confession of John E. Cooke [sic], brother of Gov. A. P. Willard, of Indiana, and one of the participants in the Harper's Ferry invasion: published for the benefit of Samuel C. Young, a non-slaveholder, who is permanently disabled by a wound received in defence of Southern institutions. Charles Town, Virginia: D. Smith Eichelberger, publisher of the Independent Democrat. November 11, 1859. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- Wheelock, Edwin M. (1859). Harper's Ferry and its lesson : a sermon for the times. By Rev. Edwin M. Wheelock, of Dover, N.H. Preached at the Music Hall, Boston, November 27, 1859. Boston: The Fraternity. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- Newhall, Rev. Fales Henry (1859). The conflict in America : a funeral discourse occasioned by the death of John Brown of Ossawattomie, who entered into rest, from the gallows, at Charlestown, Virginia, Dec. 2, 1859 : preached at the Warren St. M.E. Church, Roxbury, Dec. 4. Boston: J.M. Hewes.

- Bartholomew, J. G. (1859). "Slavery and the higher law : a sermon suggested by the execution of John Brown and delivered in Empire Hall, Aurora, Ill., on Sunday, Dec. 4th, 1859". Aurora, Illinois: Frank E. Reynolds. ISBN 9780674035171. OCLC 57551368.

- Patton, W. W. (c. 1859). The execution of John Brown; a discourse, delivered at Chicago, December 4th, 1859, in the First Congregational Church. Chicago.

- Tufts, Samuel N. (1859). Slavery, and the death of John Brown. A sermon preached in Auburn hall, Auburn, Sabbath afternoon, Dec. 11th, 1859. Lewiston.

- Hall, Nathaniel (1859). The Iniquity: A Sermon preached in The First Church, Dorchester, on Sunday, Dec. 12, 1859. Boston.

- Barker, Joseph (1859). John Brown, or the True and the False Philanthropist; with remarks on Addresses by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Wendell Phillips, and others. Philadelphia.

- Taft, S[tephen] H. (1859). A discourse on the character and death of John Brown : delivered in Martinsburgh, N. Y., Dec. 12, 1859, by S.H. Taft, Pastor of the Church of Martinsburgh. Title and link are to 2nd edition, Des Moines, 1872, since no copy could be located of the first edition. Utica, New York.

- A Citizen of Harpers Ferry (1859). Startling incidents & developments of Osowotomy Brown's insurrectory and treasonable movements at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, October 17th, 1859 : with a true and accurate account of the whole transaction. Baltimore – via Adam Matthew (subscription required).

- De Witt, Robert M. (1859). The life, trial, and conviction of Captain John Brown, known as "Old Brown of Ossawatomie," with a full account of the attempted insurrection at Harper's Ferry. Compiled from official and authentic sources. New York: The author.

- Drew, Thomas (1860). "The John Brown invasion; an authentic history of the Harper's Ferry tragedy, with full details of the capture, trial, and execution of the invaders, and of all the incidents connected therewith. With a lithographic portrait of Capt. John Brown, from a photograph by Whipple". Boston: James Campbell.

- De Witt, Robert M. (c. 1859). The life, trial and execution of Captain John Brown: known as "Old Brown of Ossawatomie," with a full account of the attempted insurrrection at Harper's Ferry. Compiled from official and authentic sources. Including Cooke's Confession, and all the Incidents of the Execution. New York: The author. Archived from the original on 2020-12-09. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "Extraordinary address of Wendell Phillips on the insurrection". New York Daily Herald. November 2, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "10,000 Copies Already Subscribed for advance of publication. The great Book of the Day!". The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts). December 23, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- Swayze, Mrs. J. C. (1859). Ossawatomie Brown; or, The Insurrection at Harper's Ferry. Samuel French.

- Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (1860). Correspondence relating to the Insurrection at Harper's Ferry, 17th October, 1859. Annapolis: Senate of Maryland.

- "The Peril of the South". New York Independent. November 5, 1859. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- DeCaro Jr., Louis A. (2002). "Fire from the Midst of You": A Religious Life of John Brown. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 081471921X.

- "Incendiary fires". Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia). December 5, 1859. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- Merod, Anna (January 22, 2019). "SU showcases virtual reality reenactment of John Brown's historic trial". Winchester Star. [Nt county, https://web.archive.org/web/20201209093242/https://www.winchesterstar.com/winchester_star/su-showcases-virtual-reality-reenactment-of-john-browns-historic-trial/article_fc582064-9830-53e3-81e1-cd32ecf0f8ca.html Archived] Check

|archive-url=value (help) from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

Further reading

- Simpson, Craig (Fall 1978). "John Brown and Governor Wise: A New Perspective on Harpers Ferry". Biography. 1 (4): 15–38. JSTOR 23539028.

- Fleming, Thomas (August 1967). "The Trial Of John Brown". American Heritage. 18 (5).

- Linder, Douglas O. "John Brown Trial (1859)". Famous Trials.

- Reports on the trial proceedings

- "[1] The Harper's Ferry Outbreak. The Preliminary Legal Proceedings in the Case of the Prisoners. Old Brown's Harangue to the Court. The Testimony of the Witnesses. The Case Sent to the Grand Jury". New York Herald. October 26, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "[2] The Harper's Ferry Outbreak. Arraignment of Old Brown and His Companions on Charges of Conspiracy, Treason and Murder. Brown Appeals for a Postponement of his Trial. Examination of Witnesses as to Brown's Physical Condition". New York Herald. October 27, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "[3] The Harper's Ferry Outbreak. The Trial of John Brown, Charged with Treason, Conspiracy and Murder. Conclusion of the for the Prosecution. Summing up for the Prosecution. The Evidence for the Prisoner. Speeches of Old Brown. He Complains of Unfairness, and Asks Them to Send for His Witnesses. The Third Day's Proceedings". New York Herald. October 29, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "[4] The Harper's Ferry Outbreak. The Trial of John Brown, Charged with Treason, Conspiracy and Murder. Conclusion of the evidence. Summing up of the Prosecution. The Fourth Day's Proceedings". New York Herald. October 31, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "[5] The Outbreak at Harper's Ferry. The Trial of John Brown, Charged with Treason, Conspiracy and Murder. The Addresses of Counsel for the Defense and Prosecution. The Proceedings of the Court. Fifth day". New York Herald. November 1, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "[6] The Harper's Ferry Affair. Argument for Arrest of Judgment in Old Brown's Case. The Trial of Coppie [sic] Commenced". New York Herald. November 2, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "[7] Closing Speech of Counsel for Defence". New York Herald. November 3, 1859. p. 4 – via newspapers.com.