John Butler (general)

John Butler (c.1728 – 1786) was a military officer in the Hillsborough District Brigade of the North Carolina militia during the American Revolutionary War from 1775 to 1784, and served as its commanding general between 1779 and the end of the conflict. He was a member of the North Carolina House of Commons for several terms simultaneously with his military service. Butler commanded soldiers in several major engagements throughout North and South Carolina, but is perhaps best remembered for his role in the Patriot defeat at the Battle of Lindley's Mill. Butler died shortly after the end of the war, and his career as a military commander has received mixed reviews by historians.

Brigadier General John Butler | |

|---|---|

| Died | 1786 |

| Allegiance | Continental Congress United States of America |

| Service/ | North Carolina state militia |

| Years of service | 1775–1784 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Southern Orange County Regiment (1776-1777) Hillsborough District Brigade (1777-1883) |

| Battles/wars | |

| Spouse(s) | Anne |

Early life and War of the Regulation

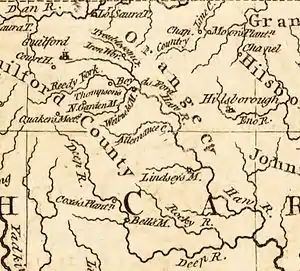

Details of Butler's early life are not readily available, although it is known that he married a woman named Anne, and that upon his death, his wife was his sole living heir.[1] At some point prior to May 1763, Butler settled on the Haw River in North Carolina near the settlement at Hawfields in what was then Orange County. Butler became sheriff of Orange County by 1770, and during the War of the Regulation, was acclaimed by the Regulators as an example of a public official who charged fair fees.[2] Butler's brother, William, was a leading Regulator, and in the aftermath of the Battle of Alamance, Butler attempted to secure a pardon for him.[3]

American Revolutionary War

With the onset of the American Revolutionary War, Butler was appointed to the Hillsborough Committee of Safety, which included Caswell, Chatham, Granville, Orange, Randolph, and Wake Counties. On September 9, 1775, Butler was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel of the Orange County Regiment of the North Carolina militia. Prior to the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge, Butler played a supporting role by occupying the Cross Creek settlement for the Patriots.[3]

Promotion and early southern campaign

On April 22, 1776, Butler was promoted to colonel of the Southern Orange County Regiment, commanding troops from the southern portion of that county. On May 9, 1777, the North Carolina General Assembly promoted Butler to brigadier general, and gave him command of the Hillsborough District Brigade of militia. In this role, Butler was often placed under the command of Continental Army generals, including his first campaign as a general in South Carolina, during which Butler and his unit of approximately 700 militiamen were placed under the immediate command of Continental brigadier general Jethro Sumner at the Battle of Stono Ferry.[3][4] In that engagement on June 20, 1779, Butler's unit, on the right flank of the Patriot lines, was restrained from engaging in a bayonet charge by commanding general Benjamin Lincoln, who believed they were too inexperienced to engage in hand-to-hand combat.[5] The North Carolina militia commanded by Butler, as well as several of the Continental regiments from that state at Stono Ferry, were nearing the end of their enlistment terms.[4] Butler subsequently commanded a force of North Carolina militia at the Battle of Camden on August 16, 1780, which ended in a major defeat for the Patriots.[3]

Guilford Courthouse

During the latter part of 1780, Butler and his command were stationed in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, defending that region against the British forces of General Charles Cornwallis. In 1781, General Nathanael Greene ordered Butler and his militia to join him in Guilford County. After the rendezvous with Greene's main army, Butler commanded his brigade of approximately 500 men at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on March 15, 1781, where they were stationed on the front line along with Brigadier General Thomas Eaton's Halifax District Brigade of the North Carolina militia.[6]

Butler and Eaton's units at Guilford Courthouse were placed along a split-rail fence facing the road on which the British were expected to advance, but former militia commander William Richardson Davie, who was present at the battle, noted that the fence provided virtually no cover, and his home state's militia were left perilously exposed.[7] Greene rode along the split-rail fence and asked the militia to fire two volleys at the British, after which Greene informed them they could withdraw from action.[8] The North Carolina militia retreated early in the battle, although Butler attempted to prevent their withdrawal.[3] Greene complained after the engagement that many North Carolina militiamen (though not specifically identified as members of Butler's brigade) fled without firing a shot at the British.[9]

After dealing a Pyrrhic victory to Cornwallis at Guilford Courthouse, Greene moved his Army south in April 1781, but Butler remained in the Hillsborough District to recruit men for Patriot units. During this time, Butler even recruited more than 240 of the militiamen who had fled at Guilford Courthouse to fight in Continental Army units under Greene's overall command.[10] Many of the men recruited, however, refused to leave the district, claiming that they were not bound by the terms of their service to leave that area.[11]

Fanning's Hillsborough raid and Butler's pursuit

On September 12, 1781, Loyalist commander David Fanning struck Hillsborough in a raid and captured Governor Thomas Burke. Fanning withdrew from Hillsborough, and attempted to take Burke to the safety of British-controlled Wilmington.[3] Butler, whose home was near Hillsborough, quickly rallied a portion of his militia to pursue Fanning.[12]

On September 13, 1781, Butler surprised Fanning at a mill site on the Cane Creek, a tributary of the Haw River, in the Battle of Lindley's Mill. Butler's forces in that engagement consisted of approximately 400 militiamen, while Fanning's force of loyalists included more than 900 men.[3] The Patriot militia, though outnumbered, had a strong defensive position at the crest of a hill on the south shore of the stream, facing the direction from which the Loyalists would be advancing.[13] The battle lasted for more than four hours, but Butler was eventually outflanked and outnumbered, and was forced to withdraw without rescuing the governor.[3] Despite his order to retreat, a contingent of Patriot militia attempted to take a stand, but that tactic was ultimately unsuccessful.[14] The Patriots suffered approximately 124 casualties, including ten men made prisoners of war, while the Loyalists suffered approximately 117 casualties.[15]

Although Butler followed Fanning intently towards Wilmington after Lindley's Mill with an increased number of volunteers,[16] the superior strength of the Loyalists, with support from the British on the lower Cape Fear River prevented another rescue attempt, and stymied Butler's advance in a confrontation near Elizabethtown.[17] By May 1782, though, Britain's fortunes in the war had waned, and Butler accepted Fanning's surrender. Butler resigned his commission on June 2, 1784, several months after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which officially ended the war.[3]

Political activity during the Revolution

Butler was active in state politics throughout the American Revolutionary War. Indeed, one historian who analyzed Butler's performance at Guilford Courthouse has noted that he was a "politician" in nature, albeit with more military experience with other such politicians like fellow militia general Thomas Eaton.[18] In 1777, Butler was elected to the North Carolina House of Commons, and was re-elected to serve in 1778 and 1784. In 1781, he served one term in the North Carolina Senate concurrently with his military duties, and between June 26, 1781 and May 3, 1782, served on the North Carolina Council of State. Butler was elected again for a term in the House of Commons in 1786, but died before taking office.[3]

Death and legacy

Butler died in the Fall of 1786, leaving his estate to his wife, Anne. Eli Caruthers, an early North Carolina historian, asserted in 1854 that Butler's performances at Lindley's Mill and Elizabethtown were lackluster. Caruthers made the claim that officers under Butler's command, particularly Colonel Robert Mebane, were justified in several incidents of insubordination in which they defied Butler's orders to retreat.[19] Scholars in the 20th century have shed further light on Butler's actions during the war, going so far as to praise Butler's conduct and tactical planning at Lindley's Mill.[1]

In 1939, the State of North Carolina designed and erected a historical marker commemorating Butler's failed rescue attempt of Governor Burke at Lindley's Mill.[20] In 2012, the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources announced that Butler's life and individual service would be commemorated by the erection of a highway historical marker in Swepsonville, North Carolina.[21]

References

Notes

- Butler 1979, p. 291.

- Kars 2002, p. 144.

- Butler 1979, p. 290.

- Rankin 1971, p. 203.

- Rankin 1971, p. 204–205.

- Babits & Howard 2009, p. 48.

- Buchanan 1997, p. 372.

- Buchanan 1997, p. 373.

- Buchanan 1997, p. 375.

- Rankin 1971, p. 323.

- Rankin 1971, p. 348.

- Caruthers 2010, p. 113.

- Caruthers 2010, p. 114.

- Caruthers 2010, p. 115–116.

- Rankin 1971, p. 365.

- Caruthers 2010, p. 124.

- Babits & Howard 2009, p. 209.

- Babits & Howard 2009, p. 60.

- Caruthers 2010, pp. 193, 197.

- "Marker: G–21 – Lindley's Mill". North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program. North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- "N.C. Highway Historical Marker Honors Provincial Patriot". Newsroom. North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. May 17, 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

Bibliography

- Babits, Lawrence E.; Howard, Joshua B. (2009). Long, Obstinate, and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3266-0.

- Buchanan, John (1997). The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-16402-X.

- Butler, Lindley S. (1979). "Butler, John". In Powell, William S (ed.). Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. Volume 1 (A-C). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1806-0., also online on NCpedia

- Caruthers, E.W. (2010). Fryar Jr., Jack E. (ed.). Revolutionary Incidents: Sketches of Character, Chiefly in the Old North State. Volume 1. Wilmington, NC: Dram Tree Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-1154-2.

- Kars, Marjoleine. (2002). Breaking Loose Together: The Regulator Rebellion in Pre-Revolutionary North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4999-6.

- Rankin, Hugh F. (1971). The North Carolina Continentals. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1154-2.