Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (August 7 [O.S. July 27] 1742 – June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependable officer, and is known for his successful command in the southern theater of the war.

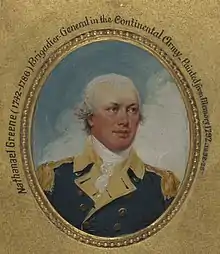

Nathanael Greene | |

|---|---|

A 1783 Charles Willson Peale portrait of Greene | |

| Nickname(s) | "The Savior of the South" "The Fighting Quaker" |

| Born | August 7 [O.S. July 27] 1742 Potowomut, Warwick Rhode Island, British America |

| Died | June 19, 1786 (aged 43) Mulberry Grove Plantation, Chatham County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Buried | Johnson Square, Savannah, Georgia, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | Continental Army |

| Years of service | 1775–1783 |

| Rank | Major general |

| Unit | Kentish Guards |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War See battles |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Signature | |

Born into a prosperous Quaker family in Warwick, Rhode Island, Greene became active in the colonial opposition to British revenue policies in the early 1770s and helped establish the Kentish Guards, a state militia. After the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, the legislature of Rhode Island established an army and appointed Greene to command it. Later in the year, Greene became a general in the newly-established Continental Army. Greene served under Washington in the Boston campaign, the New York and New Jersey campaign, and the Philadelphia campaign before being appointed quartermaster general of the Continental Army in 1778.

In October 1780, General Washington appointed Greene as the commander of the Continental Army in the southern theater. After taking command, Greene engaged in a successful campaign of guerrilla warfare against the numerically superior force of General Charles Cornwallis. He inflicted major losses on British forces at Battle of Guilford Court House, the Battle of Hobkirk's Hill, and the Battle of Eutaw Springs, eroding British control of the American South. Major fighting on land came to an end following the surrender of Cornwallis at the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781, but Greene continued to serve in the Continental Army until late 1783. After the war, he became a planter in the South, but failed. He died in 1786 at his Mulberry Grove Plantation in Chatham County, Georgia. Many places in the United States are named after Greene.

Early life and education

Greene was born on August 7, 1742 [O.S.], on Forge Farm at Potowomut in the township of Warwick, Rhode Island, which was then part of British America. He was the second son of Mary Mott and Nathanael Greene Sr., a prosperous Quaker merchant and farmer.[1] Greene was descended from John Greene and Samuel Gorton, both of whom were founding settlers of Warwick.[2] Greene had two older half-brothers from his father's first marriage, and was one of six children born to Nathanael and Mary. Due to religious beliefs, Greene's father discouraged book learning, as well as dancing and other activities.[3] Nonetheless, Greene convinced his father to hire a tutor, and he studied mathematics, the classics, law, and various works of the Age of Enlightenment.[4] At some point during his childhood, Greene gained a slight limp that would remain with him for the rest of his life.[5]

In 1770, Greene moved to Coventry, Rhode Island, to take charge of the family-owned foundry, and he built a house in Coventry called Spell Hall. Later in the year, Greene and his brothers inherited the family business after their father's death. Greene began to assemble a large library that included military histories by authors like Caesar, Frederick the Great, and Maurice de Saxe.[6]

Family

In July 1774, Greene married the nineteen-year-old Catharine Littlefield, a niece-by-marriage of his distant cousin, William Greene, an influential political leader in Rhode Island.[7] That same year, one of Greene's younger brothers married a daughter of Samuel Ward, a prominent Rhode Island politician who became an important political ally until his death in 1776.[8] Greene and Catherine's first child was born in 1776, and they had six more children between 1777 and 1786.[9]

American Revolutionary War

Prelude to war

After the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the British parliament began imposing new policies designed to raise revenue from British America for a war that colonists had played a pivotal role in instigating.[10][11] After British official William Dudington seized a vessel owned by Greene and his brothers, Greene filed an ultimately successful lawsuit against Dudington for damages. While the lawsuit was pending, Dudington's vessel was torched by a Rhode Island mob in what became known as the Gaspee Affair. In the aftermath of the Gaspee Affair, Greene became increasingly alienated from the British.[12] At the same time, Greene drifted away from his father's Quaker faith, and he was suspended from Quaker meetings in July 1773.[13] In 1774, after the passage of revenue-raising measures that colonials derided as the "Intolerable Acts," Greene helped organize a local militia known as the Kentish Guards.[14] Because of his limp, Greene was not selected as an officer in the militia.[15]

Boston campaign

The American Revolutionary War broke out with the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord. In early May, the legislature of Rhode Island established the Rhode Island Army of Observation and appointed Greene to command it. Greene's army marched to Boston, where other colonial forces were laying siege to a British garrison.[16] He missed the June 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill because he was visiting Rhode Island at the time, but he returned almost immediately after the battle and was impressed by the performance of colonial forces.[17] That same month, the Second Continental Congress established the Continental Army and appointed George Washington to command all colonial forces. In addition to Washington, Congress appointed sixteen generals, and Greene was appointed as a brigadier general in the Continental Army. Washington took command of the Siege of Boston in July 1775, bringing with him generals such as Charles Lee, Horatio Gates, and Thomas Mifflin.[18] Washington organized the Continental Army into three divisions, each consisting of regiments from different colonies, and Greene was given command of a brigade consisting of seven regiments.[19] The Siege of Boston continued until March 1776, when British forces evacuated from the city. After the end of the siege, Greene briefly served as the commander of military forces in Boston, but he rejoined Washington's army in April 1776.[20]

New York and New Jersey Campaign

Washington established his headquarters in Manhattan, and Greene was tasked with preparing for the invasion of nearby Long Island.[21] While he focused on building up fortifications in Brooklyn, Greene befriended General Henry Knox and struck up a correspondence with John Adams. He was also, along with several other individuals, promoted to major general by an act of Congress.[22] Because of a severe fever, he did not take part in the Battle of Long Island, which ended with an American retreat from Long Island.[23] After the battle, Greene urged Washington to raze Manhattan so that it would not fall into the hands of the British, but Congress forbade Washington from doing so. Unable to raze Manhattan, Washington initially wanted to fortify the city, but Greene joined with several officers in convincing Washington that the city was indefensible. During the withdrawal from Manhattan, Greene saw combat for the first time in the Battle of Harlem Heights, a minor British defeat that nonetheless represented one of the first American victories in the war.[24]

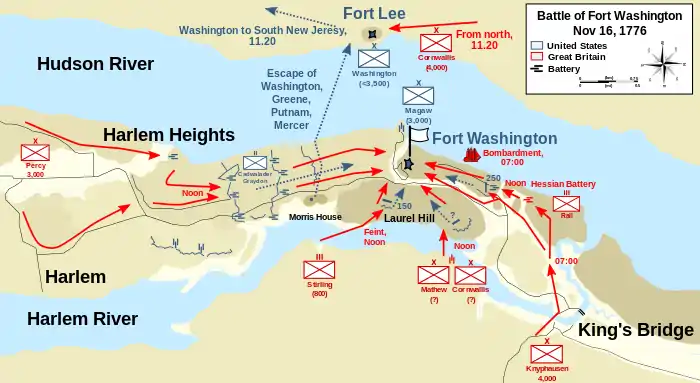

After the Battle of Harlem Heights, Washington placed Greene in command of both Fort Constitution (later known as Fort Lee), which was on New Jersey side of the Hudson River, and Fort Washington, which was across the river from Fort Constitution.[25] While in command of Fort Lee, Greene established supply depots in New Jersey along a potential line of retreat; these would later prove to be valuable resources for the Continental Army.[26] Washington suggested to Greene that he remove the garrison from Fort Washington due to its vulnerability to a British attack, but he ultimately deferred to Greene's decision to continue to station soldiers there. In the subsequent Battle of Fort Washington, fought in November 1776, the British captured the Fort Washington and its 3,000-man garrison. Greene was subjected to heavy criticism in the aftermath of the battle, but Washington declined to relieve Greene from command.[27] Shortly after the Battle of Fort Washington, a British force under General Cornwallis captured Fort Lee, and the Continental Army began a retreat across New Jersey and into Pennsylvania.[28] Greene commanded part of Washington's army in the December 1776 Battle of Trenton and the January 1777 Battle of Princeton, both of which were victories for the Continental Army.[29]

Philadelphia campaign

Along with the rest of Washington's army, Greene was stationed in New Jersey throughout the first half of 1777.[30] In July 1777, he publicly threatened to resign over the appointment of a French officer to the Continental Army, but he ultimately retained his commission.[31] Meanwhile, the British began a campaign to capture Philadelphia, the seat of Congress. At the Battle of the Brandywine, Greene commanded a division at the center of the American line, but the British launched a flanking maneuver. Greene's division helped prevent the envelopment of American forces and allowed for a safe retreat.[32] The British captured Philadelphia shortly after the Battle of the Brandywine, but Washington launched a surprise attack on a British force at the October 1777 Battle of Germantown.[33] Greene's detachment arrived late to the battle, which ended in another American defeat.[34] In December, Greene joined with the rest of Washington's army in establishing a camp at Valley Forge, located twenty-five miles northwest of Philadelphia.[35] Over the winter of 1777–1778, he clashed with Thomas Mifflin and other members of the Conway Cabal, a group that frequently criticized Washington and sought to install Horatio Gates as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army.[36]

In March 1778, Greene reluctantly accepted the position of quartermaster general, making him responsible for procuring supplies for the Continental Army.[37] Along with his top two assistants, Charles Pettit and John Cox, Greene reorganized his 3,000-person department, establishing supply depots in strategic places across the United States.[38] As quartermaster general, Greene continued to attend Washington's councils-of-war, an unusual arrangement for a staff officer.[39] After France joined the war in early 1778, the British army in Philadelphia was ordered to New York.[39] Along with Anthony Wayne and the Marquis de Lafayette, Greene recommended an attack on the British force while it retreated across New Jersey to New York. Greene commanded a division in the subsequent Battle of Monmouth, which, after hours of fighting, ended indecisively.[40]

Stalemate in the Northern theater, 1778–1780

In July 1778, Washington granted Greene temporary leave as quartermaster general so that he could take part in an attack on British forces stationed in his home state of Rhode Island.[41] The offensive was designed as a combined Franco-American operation under the command of General John Sullivan and French admiral d'Estaing, but the French fleet withdrew due to bad weather conditions.[42] Greene fought in the subsequent Battle of Rhode Island, an inconclusive battle that ended with a British retreat from the American position. After the battle, the American force under Sullivan left Rhode Island, while Greene returned to his duties as quartermaster general.[43]

After mid-1778, the Northern theater of the war became a stalemate, as the main British force remained in New York City and Washington's force was stationed nearby on the Hudson River. The British turned their attention to the Southern theater of the war, launching an ultimately successful expedition to capture Savannah.[44] Though he desired a battlefield command, Greene continued to serve as the Continental Army's quartermaster general.[45] As Congress was increasingly powerless to furnish funds for supplies, Greene became an advocate of a stronger national government.[46] In June 1780, while Washington's main force continued to guard the Hudson River, Greene led a detachment to block the advance of a British contingent through New Jersey. Despite being vastly outnumbered in the Battle of Springfield, Greene forced the withdrawal of the British force on the field.[47] Shortly after the battle, Greene resigned as quartermaster general in a letter that strongly criticized Congress; although some members of Congress were so outraged by the letter that they sought to relieve Greene of his officer's commission, Washington's intervention ensured that Greene retained a position in the Continental Army.[48] After Benedict Arnold defected to the British, Greene briefly served as the commandant of West Point and presided over the execution of John André, Arnold's contact in the British army.[49]

Command in the South

Appointment

By October 1780, the Continental Army had suffered several devastating defeats in the South under the command of Benjamin Lincoln and Horatio Gates, leaving the United States at a major disadvantage in the Southern theater of the war.[50] On October 14, 1780, Washington, acting on the authorization of Congress, appointed Greene as the commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army.[51] By the time he took command, the British were in control of key portions of Georgia and South Carolina, and the governments of the Southern states were unable to provide much support to the Continental Army. Greene would face a 6,000-man British army led by General Cornwallis and cavalry commander Banastre Tarleton, as well as numerous Loyalist militias that worked with the British. Outnumbered and under-supplied, Greene settled on a strategy of guerrilla warfare rather than pitched battles in order to prevent the advance of the British into North Carolina and Virginia.[52] His strategy would heavily depend on riverboats and cavalry to outmaneuver and harass British forces.[53] Among Greene's key subordinates in the Southern campaign were his second-in-command, Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, cavalry commander Henry Lee, the Marquis de Lafayette, Daniel Morgan, and Francis Marion.[54]

Strategic retreat

While en route to the Southern theater, Greene learned of the American victory at October 1780 Battle of Kings Mountain, which postponed Cornwallis's planned advance into North Carolina.[55] Upon arriving in Charlotte, North Carolina, in December 1780, Greene went against conventional military strategy by dividing his forces; he would lead the main American force southeast, while Morgan would lead a smaller detachment to the southwest.[56] Cornwallis responded by dividing his own forces, marching the main detachment against Greene while Tarleton led a force against Morgan. In the January 1781 Battle of Cowpens, Morgan led Continental troops to a major victory that resulted in the near-total destruction of Tarleton's force.[57] After the battle, Cornwallis set off in pursuit of Morgan, burning some of his own supplies in order to speed up his army's movement. Greene linked up with Morgan and retreated into North Carolina, purposely forcing Cornwallis away from British supply lines.[58] On February 9, in consultation with Morgan[lower-alpha 1] and other top officers, Greene decided to continue the retreat north, heading toward the Dan River at the North Carolina-Virginia border.[60]

With the British in close pursuit, Greene divided his forces, leading the main contingent north while sending a smaller group under Colonel Otho Williams to harass British forces. Greene's force outpaced the British and crossed the Dan River on February 14. Greene's contemporaries were impressed by the speed and efficiency of the retreat through difficult territory; Alexander Hamilton wrote that it was a "masterpiece of military skill and exertion." Unwilling to travel even farther from his supply lines, General Cornwallis led his army south to Hillsborough, North Carolina. On February 22, Greene's force crossed back over the Dan River to challenge Cornwallis in North Carolina.[61]

Battle of Guilford Court House

After crossing back into North Carolina, Greene harassed Cornwallis's army. In early March, he received reinforcements from North Carolina and Virginia, doubling the size of his force to approximately 4,000 men. On March 14, he led his army to Guilford Courthouse and began preparing for an attack by Cornwallis, using a strategy based on Morgan's plan at the Battle of Cowpens. Greene established three defensive lines, with the North Carolina militia making up the first line, the Virginia militia making up the second line, and the Continental Army regulars, positioned on a hill behind a small stream, making up the third line.[62] After skirmishes on the morning of the March 15, the main British force launched a full attack in the afternoon, beginning the Battle of Guilford Court House. The first American line fired volleys and then fled, either to the next line or away from the battlefield. The second line held up for longer, and continued to resist the British advance while Cornwallis ordered an unsuccessful assault against the third line. The British re-formed and launched an assault on the left flank of the third line, but were overwhelmed by Henry Lee's cavalry. In response, Cornwallis ordered his artillery to fire grapeshot into the fray, hitting British and American soldiers alike. With his army's left flank collapsing, Greene ordered a retreat, bringing the battle to an end. Although the Battle of Guilford Court House ended with an American defeat, the British suffered substantially greater losses.[63]

Campaign in South Carolina and Georgia

After the Battle of Guilford Court House, Cornwallis's force headed south to Wilmington, North Carolina. Greene initially gave chase, but declined to press to launch an attack after much of the militia returned home. To Greene's surprise, in late April Cornwallis's force began a march north to Yorktown, Virginia.[64] Rather than follow Cornwallis, Greene headed South, where he challenged British commander Francis Rawdon for control of South Carolina and Georgia.[65] On April 20, he began a siege of Camden, South Carolina and established a camp at a nearby ridge known as Hobkirk's Hill. On the 25th, Rawdon launched a surprise attack on Greene's position, beginning the Battle of Hobkirk's Hill. Despite having been taken by surprise, Greene's force nearly achieved victory, but the left flank collapsed and the cavalry failed to arrive. Facing total defeat, Greene ordered a retreat, bringing an end to the battle. Although the American and British forces suffered a similar number of losses in the Battle of Hobkirk's Hill, Greene was deeply disappointed by the result of the battle.[66]

On May 10, Rawdon's force left Camden for Charleston, South Carolina, effectively conceding control of much of interior South Carolina to the Continental Army. In a series of small actions known as the "war of the posts," Greene and his subordinates further eroded British control of interior South Carolina by capturing several British forts.[67] On June 18, after undertaking the month-long Siege of Ninety-Six, Greene launched an unsuccessful attack on the British fort at Ninety Six, South Carolina. Although the assault failed, Rawdon ordered the fort abandoned shortly thereafter. Meanwhile, Greene's subordinates further expanded Continental control, capturing Augusta, Georgia on June 5. By the end of June, the British controlled little more than a thin strip of coastal land from Charleston to Savannah.[68] After resting through much of July and August, the Continental Army resumed operations and engaged a British force on September 8 at the Battle of Eutaw Springs.[69] The battle ended with a Continental retreat, but the British suffered more substantial losses. After the battle, the British force returned to Charleston, leaving interior South Carolina in full control of Continental forces. Congress issued Greene a gold medal and passed a resolution congratulating him for his victory at Eutaw Springs.[70]

While Greene campaigned in South Carolina and Georgia, Lafayette led Continental resistance to Cornwallis's army in Virginia. Although Greene's command gave him leadership of Continental operations in Virginia, he was unable to closely control events in Virginia from South Carolina. Lafayette heeded Greene's advice to avoid combat, but his force only narrowly escaped destruction at the July 1781 Battle of Green Spring. In August, Washington and French general Rochambeau left New York for Yorktown, intent on inflicting a decisive defeat against Cornwallis.[71] Washington laid siege to Cornwallis at Yorktown, and Cornwallis surrendered on October 19.[72]

After Yorktown

Yorktown was widely regarded as a disastrous defeat for the British, and many considered the war to have effectively ended in late 1781.[73] The governments of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia each voted Greene liberal grants of lands and money, including an estate called "Boone's Barony" in Bamberg County, South Carolina, and Mulberry Grove Plantation near Savannah.[74] Nonetheless, the British still controlled New York, Savannah, and Charleston, and Greene still contended with Loyalist militias who sought to destabilize Continental control. With American finances in a disastrous state, Greene also struggled to clothe and feed his troops. In late 1781, he declined appointment to the newly-created position of secretary of war, which was charged with overseeing the Continental Army.[75] He also corresponded with Robert Morris, the superintendent of finance of the United States, who shared Greene's view on the need for a stronger national government than the one that had been established in the Articles of Confederation.[76] No major military action occurred in 1782, and the British evacuated Savannah and Charleston before the end of that year.[77] Congress officially declared the end of the war in April 1783, and Greene resigned his commission in late 1783.[78]

Later life and death

After resigning his commission, Greene returned to Newport. Facing a large amount of debt, he relocated to the South to focus on the plantations he had been awarded during the war, and he made his home at the Mulberry Grove Plantation outside of Savannah. Though he had spoken against slavery earlier in his life, Greene purchased slaves to work his plantations.[79] In 1784, Greene declined appointment to a commission tasked with negotiating treaties with Native Americans, but he agreed to attend the first meeting of the Society of the Cincinnati.[80] He then became an original member with the Rhode Island Society of the Cincinnati.[81]

Greene fell ill on June 12, 1786, and he died at Mulberry Grove on June 19, 1786, at the age of 43.[82] For over a century, his remains were interred at the Graham Vault in Colonial Park Cemetery in Savannah, alongside John Maitland, his arch-rival in the conflict.[83] On November 14, 1902, through the efforts of Rhode Island Society of the Cincinnati President Asa Bird Gardiner, his remains were moved to a monument in Johnson Square in Savannah.[84]

As noted above, Greene was in debt. In 1782 and 1783, Greene had difficulty supplying his troops in Charleston with clothing and provisions. He contracted with Banks & Co to furnish supplies, but was compelled to put his name to the bond for the supplies. An order was given by Greene to Robert Morris for payment of the amount; this was paid by the Government of the United States to the contractor, who did not use it to pay the debt and left the bond unpaid. Greene paid the debt himself, and in 1791 his executrix petitioned Congress for relief. Greene had obtained some security from a partner of Banks & Co named Ferrie on a mortgage or lien on a tract of land, but the land was liable to a prior mortgage of £1,000 sterling to an Englishman named Murray. In 1788, the mortgagor in England filed a bill to foreclose on the mortgage, while Greene's family instituted proceedings against Ferrie, who was entitled to a reversionary interest in the land. The court ordered the land be sold and the sale proceeds to be first used to extinguish the mortgage, with the balance to go to representatives of General Greene. The land was sold, and after the £1,000 mortgage had been paid off, the residue of £2,400 was to go Greene's representatives. However, the purchaser never took title and never paid the money, on the grounds that the title was in dispute. In 1792 a Relief Act was passed by Congress for General Greene which was based upon the decree of the land sale; the sum of which he was entitled to (£2,400) was exempted out of the indemnity allowed him at that time, not one cent of which his heirs received except $2,000. In 1830, the administrators of Murray filed a bill of Chancery against the land; however, his agent who had bought the land had not taken title to it, on the grounds that there was a dispute about the land. The claim to the title was not resolved and the money never paid. Meanwhile, from 1789 to 1840, the plantation had gone to ruin; under the original decree, the land, instead of bringing the sum it had first bought, was sold for only $13,000. This left Greene's representatives only about $2,000 instead of £2,400. In 1840, they applied to Congress for the difference between the two sums. In 1854, the case was put to Congress for the relief of Phineas Nightingale, who was the administrator of the deceased General Greene.[85]

Legacy

Historical reputation

Defense analyst Robert Killebrew writes that Greene was "regarded by peers and historians as the second-best American general" in the Revolutionary War, after Washington.[86] The historian Russell Weigley believed that "Greene's outstanding characteristic as a strategist was his ability to weave the maraudings of partisan raiders into a coherent pattern, coordinating them with the maneuvers of a field army otherwise too weak to accomplish much, and making the combination a deadly one.... [He] remains alone as an American master developing a strategy of unconventional war."[86] Historian Curtis F. Morgan Jr. describes Greene as Washington's "most trusted military subordinate."[87] According to Golway, "on at least two occasions, fellow officers and politicians described Greene... as the man Washington had designated to succeed him if he were killed or captured."[88] He was also respected by his opponents; Cornwallis wrote that Greene was "as dangerous as Washington. He is vigilant, enterprising, and full of resources–there is but little hope of gaining an advantage over him."[89] Alexander Hamilton wrote that Greene's death deprived the country of a "universal and pervading genius which qualified him not less for the Senate than for the field."[90] Killebrew argues that Greene was the "most underrated general" in American history.[86]

Memorials

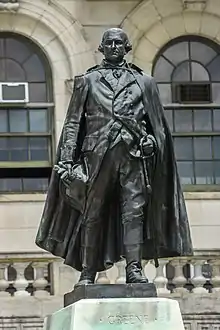

His statue, along with that of Roger Williams, represents the state of Rhode Island in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol. Washington, D.C. also hosts a bronze equestrian statue of Greene in Stanton Park. A large oil portrait of Nathanael Greene hangs in the State Room in the Rhode Island State House, and a statue stands outside the building's south facade. A cenotaph to him stands in the Old Forge Burial Ground in Warwick.[91] Greene is also memorialized by statues in or near Philadelphia, Valley Forge National Historical Park, Greensboro,[92] Greensburg, Pennsylvania, and Greenville, South Carolina. The Nathanael Greene Monument in Savannah, Georgia serves as his burial place.

Numerous places and things have been named after Greene across in the United States. Fourteen counties are named for Greene, the most populous of which is Greene County, Missouri. Municipalities named for Greene include Greensboro, North Carolina; Greensboro, Georgia; Greensboro, Pennsylvania; Greenville, North Carolina; Greenville, South Carolina and Greeneville, Tennessee. Other things named for Greene include the Green River in Kentucky, Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn, and several schools. Several ships have been named for Greene, including the USRC General Green, the USS General Greene, the USS Nathanael Greene, and the USAV MGen Nathanael Greene.

The Nathanael Greene Homestead in Coventry, Rhode Island, features Spell Hall, which was General Greene's home, built in 1774. Greene commissioned cabinetmaker Thomas Spencer to build a desk and bookcase, likely to be put in this new home. The desk and bookcase is now at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia. It was built in East Greenwich, Rhode Island in the Chippendale Style. An inscription is written in graphite on an interior drawer that says that the desk originally belonged to Nathanael Greene.[93]

Notes

- Morgan retired shortly after the council-of-war due to health issues.[59]

References

- Golway (2005), pp. 12–15

- Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. pp. 88, 302, 344. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.

- Golway (2005), pp. 14–16, 19

- Golway (2005), pp. 21–23

- Golway (2005), pp. 19–20

- Golway (2005), pp. 28–30

- Golway (2005), pp. 42–43

- Golway (2005), pp. 30, 84

- Golway (2005), pp. 74, 312–313

- "George Washington starts the French & Indian War – On This Day – May 28, 1754". Revolutionary War and Beyond. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- Golway (2005), pp. 23–24

- Golway (2005), pp. 32–38

- Golway (2005), pp. 38–39

- Golway (2005), pp. 40–44

- Golway (2005), pp. 44–45

- Golway (2005), pp. 45–47

- Golway (2005), pp. 55–56

- Golway (2005), pp. 56–57

- Golway (2005), pp. 60–61

- Golway (2005), pp. 75–78

- Golway (2005), pp. 79–80

- Golway (2005), pp. 82–85

- Golway (2005), pp. 90–91

- Golway (2005), pp. 92–95

- Golway (2005), pp. 95–98

- Golway (2005), pp. 97–98, 117

- Golway (2005), pp. 100–103

- Golway (2005), pp. 104–106

- Golway (2005), pp. 108–111, 116–117

- Golway (2005), pp. 132–133

- Golway (2005), pp. 128–130

- Golway (2005), pp. 136–139

- Golway (2005), pp. 142–144

- Golway (2005), pp. 145–147

- Golway (2005), pp. 153–100

- Golway (2005), pp. 154–157

- Golway (2005), pp. 164–166

- Golway (2005), pp. 170–171

- Golway (2005), pp. 173–174

- Golway (2005), pp. 175–177

- Golway (2005), pp. 183–184

- Golway (2005), pp. 186–189

- Golway (2005), pp. 191–192

- Golway (2005), pp. 194, 208–209

- Golway (2005), pp. 199–202

- Golway (2005), p. 215

- Golway (2005), pp. 222–225

- Golway (2005), pp. 225–227

- Golway (2005), pp. 7, 229–230

- Golway (2005), pp. 5–9

- Golway (2005), pp. 9, 230

- Golway (2005), pp. 231–233

- Golway (2005), p. 238

- Golway (2005), pp. 233–239, 266

- Golway (2005), pp. 235–236

- Golway (2005), pp. 238–242

- Golway (2005), pp. 245–247

- Golway (2005), pp. 248–249

- Golway (2005), p. 250

- Golway (2005), pp. 250–251

- Golway (2005), pp. 250–253

- Golway (2005), pp. 253–256

- Golway (2005), pp. 257–260

- Golway (2005), pp. 261–264

- Golway (2005), pp. 264–265

- Golway (2005), pp. 266–269

- Golway (2005), pp. 270–272

- Golway (2005), pp. 274–276

- Golway (2005), pp. 279–280

- Golway (2005), pp. 283–286

- Golway (2005), pp. 278–279

- Golway (2005), pp. 287–288

- Golway (2005), pp. 289, 294

- Siry, Steven E. (2006). Greene : Revolutionary General. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 86. ISBN 9781574889123.

- Golway (2005), pp. 289–292

- Rappleye, Charles (2010). Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution. Simon and Schuster. p. 270. ISBN 9781416572862.

- Golway (2005), pp. 301–303

- Golway (2005), pp. 303–306

- Golway (2005), pp. 308–310

- Golway (2005), pp. 310–311

- Metcalf, Bryce (1938). Original Members and Other Officers Eligible to the Society of the Cincinnati, 1783-1938: With the Institution, Rules of Admission, and Lists of the Officers of the General and State Societies. Strasburg, VA: Shenandoah Publishing House, Inc. p. 145.

- Golway (2005), pp. 313–314

- Galileo

- Nathanael Greene: a biography of the American Revolution

- The Congressional Globe, Volume 23, Part 3 p.1581

- Ricks, Thomas E. (September 22, 2010). "The most underrated general in American history: Nathaniel Greene?". Foreign Policy. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Morgan Jr., Curtis F. "Nathanael Greene". George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Golway (2005), pp. 3–4

- Golway (2005), p. 244

- Golway (2005), p. 314

- Graves of our Founders

- Statue of Nathanael Greene in Downtown Greensboro. Greensboro Daily Photo (February 19, 2009). Retrieved on July 23, 2013.

- "Desk and bookcase, RIF1447". The Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

Bibliography

Secondary sources

- Babits, Lawrence E.; Howard, Joshua B. (2009). Long, Obstinate, and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807887677.

- Buchanan, John (1999). The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. ISBN 9781620456026.

- Carbone, Gerald M. (2008). Nathanael Greene: A Biography of the American Revolution. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230602717.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Author:Nathanael Greene". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Author:Nathanael Greene". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.- Greene, Francis Vinton, "Life of Nathanael Greene, Major-General in the Army of the Revolution". (New York, 1893), in the Great Commanders Series

- Greene, George W. The Life of Nathanael Greene, Major-General in the Army of the Revolution. 3 vols. New York: Putnam, 1867–1871. Reprinted Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1972. ISBN 0-8369-6910-3.

- Golway, Terry (2005). Washington's General: Nathanael Greene and the Triumph of the American Revolution. Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 0-8050-7066-4.

- Haw, James (2008). "Every Thing Here Depends upon Opinion: Nathanael Greene and Public Support in the Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution". South Carolina Historical Magazine. 109 (3): 212–231. JSTOR 40646853.

- Johnson, William, "Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene", (1822)

- Massey, Gregory D.; Piecuch, Jim, eds. (2012). General Nathanael Greene and the American Revolution in the South. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1611170696.

- McCullough, David (2005). 1776. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743226714.

- Middlekauff, Robert (2005). The Glorious Cause: the American Revolution, 1763–1789. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195162479.

- Oller, John (2016). The Swamp Fox: How Francis Marion Saved the American Revolution. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82457-9.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (2018). In the Hurricane's Eye: The Genius of George Washington and the Victory at Yorktown. Viking. ISBN 978-0525426769.

- Siry, Steven E. (2006). Greene: Revolutionary General. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9781574889123.

- Stegeman, John F. (1985) [1977]. Caty: A Biography of Catharine Littlefield Greene. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820307923.

- Thane, Elswyth (1972). The Fighting Quaker: Nathanael Greene. Hawthorn Books. ISBN 978-0884119715.

- Ward, Christopher. War of the Revolution 2 Volumes. New York 1952

Primary sources

- The Papers of General Nathanael Greene. University of North Carolina Press:

- Vol. I: December 1766 to December 1776. ISBN 0-8078-1285-4.

- Vol. II: January 1777 to October 16, 1778. ISBN 0-8078-1384-2

- Vol. III: October 18, 1778 to May 10, 1779. ISBN 0-8078-1557-8.

- Vol. IV: May 11, 1779 to October 31, 1779. ISBN 0-8078-1668-X.

- Vol. V: November 1, 1779 to May 31, 1780. ISBN 0-8078-1817-8.

- Vol. VI: June 1, 1780 to December 25, 1780. ISBN 0-8078-1993-X.

- Vol. VII: December 26, 1780 to March 29, 1781. ISBN 0-8078-2094-6.

- Vol. VIII: March 30, 1781 to July 10, 1781. ISBN 0-8078-2212-4.

- Vol. IX: July 11, 1781 to December 2, 1781. ISBN 0-8078-2310-4.

- Vol. X: December 3, 1781 to April 6, 1782. ISBN 0-8078-2419-4.

- Vol. XI: April 7, 1782 to September 30, 1782. ISBN 0-8078-2551-4.

- Vol. XII: 1 October 1782 to May 21, 1783. ISBN 0-8078-2713-4.

- Vol. XIII: May 22, 1783 to June 13, 1786. ISBN 0-8078-2943-9.

External links

- American Revolution Institute

- Biography of Greene

- A letter from Nathanael Greene with his acceptance of command over the Southern Army from the Papers of the Continental Congress

- Historic Valley Forge biography

- American Revolution homepage

- Army Quartermaster Foundation, Inc.

- “Eulogium on Major-General Greene” (1789) by Alexander Hamilton

- Gen Nathl Greene descendants, as listed in a family tree on RootsWeb

- Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, by William Johnson

- Nathanael Greene Monument historical marker

- Nathanael Greene, Maj. Gen. Continental Army historical marker

- Society of the Cincinnati

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Stephen Moylan |

Quartermaster General of the United States Army 1778–1780 |

Succeeded by Timothy Pickering |