Jordan Lake

B. Everett Jordan Lake is a reservoir in New Hope Valley, west of Cary and south of Durham in Chatham County, North Carolina, in the United States; the northernmost end of the lake extends into southwestern Durham County.

| B. Everett Jordan Lake | |

|---|---|

The sun rising over Jordan Lake, taken from Farrington Road | |

B. Everett Jordan Lake  B. Everett Jordan Lake | |

| Location | Chatham / Durham counties, North Carolina, United States |

| Coordinates | 35°45′0″N 79°1′30″W |

| Lake type | Reservoir |

| Primary inflows | Haw River, New Hope Creek, Morgan Creek, and Little Creek |

| Primary outflows | Haw River |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Managing agency | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| Max. length | 16 miles (26 km)[1] |

| Max. width | 5 miles (8.0 km)[1] |

| Surface area | 13,940 acres (56.4 km2) 31,800 acres (129 km2) flood control pool[1] |

| Average depth | 14 feet (4.3 m)[1] |

| Max. depth | 140 feet (43 m)[1] |

| Water volume | 45,800 acre feet (56.5 hm3) |

| Shore length1 | 180 mi (290 km)[1] |

| Surface elevation | 216 ft (66 m) [1] |

| Frozen | never |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

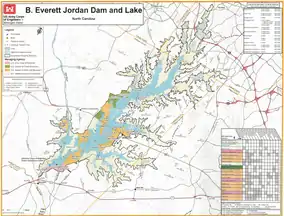

Part of the Jordan Lake State Recreation Area,[1] the reservoir covers 13,940 acres (5,640 ha) with a shoreline of 180 miles (290 km) at its standard water level of 216 feet (66 m) above sea level. It was developed as part of a flood control project prompted by a particularly damaging tropical storm that hit the region downstream in September 1945. Constructed at an original cost of US $146,300,000, it is owned and operated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, which dammed and flooded the Haw River and New Hope River between 1973 and 1983.

Construction

The Jordan Lake Dam (also known as the B. Everett Jordan Project and the New Hope Dam) is located at 35°39′15″N 79°4′0″W 4 miles (6 km) upstream from the mouth of the Haw River in the upper Cape Fear River drainage basin. Completed in 1974 by the Nello L. Teer Company, it is 1,330 feet (405 m) in length and has a top elevation of 266.5 feet (81 m) above mean sea level.[1]

During the construction of the reservoir, much of the area was permanently changed. The Durham and South Carolina Railroad was relocated from the New Hope basin to higher ground but its stations were not rebuilt, and the line itself was soon abandoned.[2] Many farming families were relocated as the project was developed and several roads in eastern Chatham County were either rerouted or taken out of commission completely. Some of the roads were never demolished, but simply allowed to flood over. When the lake is at low water volume, many of these roads can still be seen and some have even been utilized for makeshift boat ramps.

Originally authorized in 1963 as the New Hope Lake Project, the reservoir was renamed in 1974 in memory of B. Everett Jordan, former US Senator from North Carolina.

Water supply

Jordan Lake serves as a major water supply for about 250,000 (1990) people in North Carolina. Allocations made in 2002 total 63 mgd. Governmental units allocated water from Jordan Lake are Towns of Cary and Apex (32 mgd), Chatham County (6 mgd), City of Durham (10 mgd), Town of Holly Springs (2 mgd), Town of Morrisville (3.5 mgd), Orange County (1 mgd), Orange Water & Sewer Authority (5 mgd), and Wake County - RTP South (3.5 mgd). As of 2014 the NCDENR Division of Water Resources is conducting a round of applications for water allocation.[3][4][5]

Water quality

Jordan Lake was declared as nutrient-sensitive waters (NSW) by the North Carolina Environmental Management Commission from 1983, the year it was impounded. The lake is eutrophic or hyper-eutrophic owing to excessive nutrient levels.[6]

Requirements of the federal Clean Water Act were triggered when the lake became impaired, including the need to set load reduction limits for point and nonpoint sources and enforce discharge limits.[7]

The Jordan Lake Rules are designed to improve water quality in the lake. The rules were developed with extensive meetings, public hearings and negotiations between residents, environmental groups, local and state government agencies and other stakeholders. The rules mandate reducing pollution from wastewater discharges, stormwater runoff from new and existing development, agriculture and fertilizer application.[8][9]

From July 2011 several NC laws have been passed delaying and weakening the rules, culminating in a plan to deploy floating arrays of in-lake circulators intended to reduce harmful algae and excessive chlorophyll.[10][11] However, they proved ineffective in a testing program and were removed in 2016.

On December 21, 2017 Researchers at Duke University have discovered elevated levels of several perfluorinated compounds an unregulated family of industrial chemicals including some that can raise cancer risks in Jordan Lake and drinking water treated by the town of Cary. Cary water treatment officials, who have independently confirmed the findings of Duke researchers, say the town's water is safe to drink. They also point out that the compounds detected are still below health advisory levels set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Testing still continues as of March 8, 2018.[12]

Shoreline trash cleanup

Bald eagle habitat being endangered by trash submerged by the lake's creation spurred volunteer efforts to clean up the shoreline and other sensitive areas.[13][14]

In 2009 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers worked with local activists to establish Clean Jordan Lake, a nonprofit "friends of the lake" group.[15][16] Volunteer cleanups aided by the Corps of Engineers began in 2010.[17][18] Since then, Clean Jordan Lake has organized over 300 community service cleanups, formed the Adopt-A-Shoreline Program that comprises 19 groups that clean habitually littered areas three times per year, and formed the Adopt-A-Feeder Stream Program with semi-annual cleanups to prevent trash from reaching the lake. As of late 2017, 5,600 volunteers have removed 13,500 bags of trash (enough to fill 40 large dumpsters) and 4,300 tires. Clean Jordan Lake estimates that 80% of the trash is from stormwater runoff and 20% from recreational use of the lake.[19][20]

References

- US Army Corps of Engineers. "B Everett Jordan Dam and Lake". Brochure.

- Capehart, Al. "Durham to Duncan – Norfolk Southern" (PDF). Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Clean Jordan Lake

- NCDENR DWR Permits & Registration » Jordan Lake Water Supply Allocation

- NCDENR DWR Current Allocations

- NCDENR DWR Background

- Brief History of Jordan Nutrient Strategy

- NCDENR DWR Jordan Lake Rules

- Jordan Lake Rules fact sheet

- NCDENR - Read the Rules

- Using Circulators to Control Wastewater Pond Odors

- WRAL. "Elevated levels of unregulated chemicals found in Jordan Lake, Cary drinking water :: WRAL.com". WRAL.com. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- News & Observer: Debris clogs Jordan Lake's coves Archived 2012-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- NBC 17: Volunteers Sought For Trash Removal In Jordan Lake

- cleanjordanlake.org

- Independent Weekly: Jordan Lake: Turtles, herons and Styrofoam

- Curliss, J. Andrew (May 12, 2010). "Littered lake gets a cleanup". NewsObserver.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2010. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- NBC 17: Volunteers Wanted To Clean Up Jordan Lake

- http://chathamcountyline.org/pdfs/CCL.may17.web.pdf

External links

- B. Everett Jordan Dam and Lake Corps of Engineers

- Jordan Lake project - U.S. Corps of Engineers

- Permits & Registration » Jordan Lake Water Supply Allocation

- Jordan Lake Dam - Lakes Online

- US Army Corps of Engineers, Wilmington District, Water Management Unit, Project Information

- Jordan Lake water level graph (1983-present)