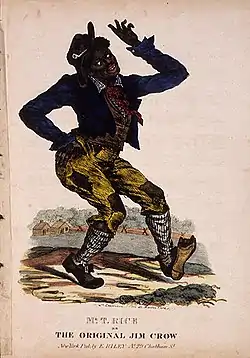

Jump Jim Crow

"Jump Jim Crow" or "Jim Crow" is a song and dance from 1828 that was done in blackface by white minstrel performer Thomas Dartmouth (T. D.) "Daddy" Rice. The song is speculated to have been taken from Jim Crow (sometimes called Jim Cuff), a physically disabled African slave, who is variously claimed to have lived in St. Louis, Cincinnati, or Pittsburgh.[1][2] The song became a great 19th-century hit and Rice performed all over the country as "Daddy Pops Jim Crow".

| "Jump Jim Crow" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Song | |

| Written | 1828 |

| Published | 1832 |

| Songwriter(s) | Thomas D. Rice |

"Jump Jim Crow" was a key initial step in a tradition of popular music in the United States that was based on the racist "imitation" and mockery of black people. The first song sheet edition appeared in the early 1830s, published by E. Riley. A couple of decades saw the mockery genre explode in popularity with the rise of the minstrel show.

The song originally printed used "floating verses", which appear in altered forms in other popular folk songs. The chorus of the song is closely related to the traditional Uncle Joe / Hop High Ladies; some folklorists consider "Jim Crow" and "Uncle Joe" to be a single, continuous family of songs.[3]

As a result of Rice's fame, the term Jim Crow had become a pejorative term for African Americans by 1838[4] and from this the laws of racial segregation became known as Jim Crow laws.

Lyrics

The lyrics as most commonly quoted are:

Come, listen all you gals and boys, Ise just from Tuckyhoe;

I'm goin' to sing a little song, My name's Jim Crow.

CHORUS [after every verse]

Weel about and turn about and do jis so,

Eb'ry time I weel about I jump Jim Crow.

I went down to the river, I didn't mean to stay;

But dere I see so many gals, I couldn't get away.

And arter I been dere awhile, I tought I push my boat;

But I tumbled in de river, and I find myself afloat.

I git upon a flat boat, I cotch de Uncle Sam;

Den I went to see de place where dey kill'd de Pakenham.

And den I go to Orleans, an, feel so full of flight;

Dey put me in de calaboose, an, keep me dere all night.

When I got out I hit a man, his name I now forgot;

But dere was noting left of him 'cept a little grease spot.

And oder day I hit a man, de man was mighty fat

I hit so hard I nockt him in to an old cockt hat.

I whipt my weight in wildcats, I eat an alligator;

I drunk de Mississippy up! O! I'm de very creature.

I sit upon a hornet's nest, I dance upon my head;

I tie a wiper round my neck an, den I go to bed.

I kneel to de buzzard, an, I bow to the crow;

An eb'ry time I weel about I jump jis so.

Standard English

Other verses, quoted in non-dialect standard English:

Come, listen, all you girls and boys, I'm just from Tuckahoe;

I'm going to sing a little song, My name's Jim Crow.

Chorus: Wheel about, and turn about, and do just so;

Every time I wheel about, I jump Jim Crow.

I went down to the river, I didn't mean to stay,

But there I saw so many girls, I couldn't get away.

I'm roaring on the fiddle, and down in old Virginia,

They say I play the scientific, like master Paganini,

I cut so many monkey shines, I dance the galoppade;

And when I'm done, I rest my head, on shovel, hoe or spade.

I met Miss Dina Scrub one day, I give her such a kiss;

And then she turn and slap my face, and make a mighty fuss.

The other girls they begin to fight, I told them wait a bit;

I'd have them all, just one by one, as I thought fit.

I whip the lion of the west, I eat the alligator;

I put more water in my mouth, then boil ten loads of potatoes.

The way they bake the hoe cake, Virginia never tire.

They put the dough upon the foot,

Variants

As he extended it from a single song into an entire minstrel revue, Rice routinely wrote additional verses for "Jump Jim Crow". Published versions from the period run as long as 66 verses; one extant version of the song, as archived by American Memory, includes 150 verses.[5] Verses range from the boastful doggerel of the original version to an endorsement of President Andrew Jackson (known as "Old Hickory"); his Whig opponent in the 1832 election was Henry Clay:[6]

Old hick'ry never mind de boys

But hold up your head;

For people never turn to clay

'Till arter dey be dead.[7]

Other verses by Rice, also from 1832, demonstrate anti-slavery sentiments and cross-racial solidarity that were rarely found in later blackface minstrelsy:[7]

Should dey get to fighting,

Perhaps de blacks will rise,

For deir wish for freedom,

Is shining in deir eyes.

And if de blacks should get free,

I guess dey'll see some bigger,

An I shall consider it,

A bold stroke for de nigger.

I'm for freedom,

An for Union altogether,

Although I'm a black man,

De white is call'd my broder.[7]

Origins

The origin of the name "Jim Crow" is obscure but may have evolved from the use of the pejorative "crow" to refer to black people in the 1730s.[8] Jim may be derived from "Jimmy", an old cant term for a crow, which is based on a pun for the tool "crow" (crowbar). Before 1900, crowbars were called "crows" and a short crowbar was and still is called a "jimmy" ("jemmy" in British English), a typical burglar's tool.[9][10][11] The folk concept of a dancing crow predates the Jump Jim Crow minstrelsy and has its origins in the old farmer's practice of soaking corn in whiskey and leaving it out for the crows. The crows eat the corn and become so drunk that they cannot fly, but wheel and jump helplessly near the ground, where the farmer can kill them with a club.[12][13][14]

See also

References

- "An Old Actor's Memories; What Mt. Edmon S. Conner Recalls About His Career" (PDF). The New York Times. June 5, 1881. p. 10. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- Hutton, Michael (Jun–Dec 1889). "The Negro on the Stage". Harpers Magazine. Harper's Magazine Co. 79: 131–145. Retrieved March 10, 2010., see pages 137-138

- Alternative lyrics at Blugrassmessenger.com

- Woodward, C. Vann and McFeely, William S. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. 2001, page 7

- Alternative lyrics at Blugrassmessengers.com

- Strausbaugh 2006, pp. 92–93

- Strausbaugh 2006, p. 93

- I Hear America Talking by Stuart Berg Flexner, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1976, page 39; possibly also Robert Hendrickson, The Dictionary of Eponyms: Names That Became Words (New York: Stein and Day, 1985), ISBN 0-8128-6238-4, possibly page 162 (see edit summary for explanation).

- Lockwood's dictionary of terms used in the practice of mechanical engineering by Joseph Gregory Horner (1892).

- For example, in the New York statutes on burglary it reads: "... having in his possession any pick-lock, key, crow, jack, bit, jimmy, nippers, pick, betty or other implement of burglary ..."

- John Ruskin in Flors Clavigera writes: "... this poor thief, with his crow-bar and jimmy" (1871).

- "Sometimes he made the crows drunk on corn soaked in whiskey, and as they reeled among the hillocks, knocked them on the head", "A Legend of Crow Hill". The World at Home: A Miscellany of Entertaining Reading. Groombridge & Sons, London (1858), page 68.

- "Somebody baited a field-fall of crows, once, with beans soaked in brandy; whereby they got drunk.", "Talking of Birds". The Columbian Magazine, July 1844, p. 7 (p. 350 of PDF document).

- "Soak a few quarts of dried corn in whiskey, and scatter it over the fields for the crows. After partaking one such meal and getting pretty thoroughly corned, they will never return to it again." The Old Farmers Almanac, 1864.

Further reading

- Lyrics and background from the Bluegrass Messengers

- In Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Charles Mackay, pg 629-630, reported his dismay at hearing the song in London.

- Scandalize My Name: Black Imagery in American Popular Music, by Sam Dennison (1982, New York)

- Strausbaugh, John (8 June 2006). Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult and Imitation in American Popular Culture. Jeremy P. Tarcher / Penguin. ISBN 978-1-58542-498-6.