Kanta (play)

Kanta (pronounced [kɑnta]) is an 1882 Gujarati play by Manilal Dwivedi, based on a historical event; the killing of King Jayshikhari of Patan by King Bhuvad of Panchasar. Dwivedi added the characters of Tarala, Haradas and Ratnadas from his own imagination and gave dramatic twists to the original story in order to make the story more suitable for a dramatic retelling. It has been called the most outstanding play of the 19th century in Gujarati literature. Reportedly, the play has elements of Sanskrit drama and Shakespearean tragedy reflected in its construction, due to Dwivedi's recent translation of Sanskrit play Malatimadhavam and studies of Shakespeare's plays. Kanta had moderate success on the stage. The Mumbai Gujarati Natak Mandali inaugurated its theatrical activities by staging this play on 29 June 1889.

| Kanta | |

|---|---|

Cover of 4th edition (1954) | |

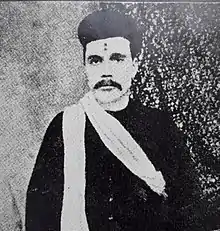

| Written by | Manilal Dwivedi |

| Characters |

|

| Date premiered | 29 June 1889 |

| Original language | Gujarati |

| Genre | Tragedy |

Overview

Dwivedi was a scholar, poet, novelist, philosopher and editor of Priyamvada and Sudarshan. He had translated the Sanskrit play Malatimadhavam by Bhavabhuti into Gujarati just before he started writing Kanta. During 1881–1882, when Kanta was being written, he was translating a second play by Bhavabhuti, Uttararamacarita, at the same time. Also, he studied Shakespeare's plays, which were fresh in his mind. Hence, certain elements of Sanskrit drama and Shakespearean tragedy are reflected in the construction of this play.[1] The play is a mixture of history, imagination, and the author's preference for the traditional values and way of life, and it portrayed, for the first time, a tragic hero in Gujarati drama.[2]

Its basis is a historical event, the killing of King Jayshikhari of Patan by King Bhuvad of Panchasar. Dwivedi added the characters of Tarala, Haradas and Ratnadas from his own imagination and gave dramatic twists to the original story.[1]

Characters

The principal characters are:[3]

- Jaychandra – King of Patan

- Yauvanashri – queen and wife of Jaychandra

- Sursen – friend and brother-in-law of Jaychandra and army chief

- Kanta – wife of Sursen

- Tarala – maid of Yauvanashri

- Bhuvanaditya – King of Kalyan

- Karan – son of Bhuvanaditya

- Haradas – friend of Sursen

- Ratnadas – wicked friend of Karan

- Bhils, citizens, soldiers, servants, etc.

Plot

Jaychandra, the king of Patan, is informed of a surprise attack from his lifelong enemy Bhuvanaditya, who was defeated by him in the past. He asks his trusted friend and brother-in-law Sursen, who is also the chief of the army, to go to a nearby forest and leave the pregnant queen Yauvanashri under the protection of kind Bhils, so that in case of an unfavorable outcome of the battle, the child to be born may survive to take revenge. Sursen, who preferred to face the enemy, unwillingly proceeds to the forest to leave the queen under the care of Bhils. He also leaves his wife Kanta and faithful maid Tarala to look after the queen in the forest. When Sursen leaves, he gives his pearl necklace to Kanta, saying that the necklace, which is a symbol of his devotion to her, would be snapped asunder only when he dies.[1]

By the time Sursen returns from the forest, the battle is over. Jaychandra is killed and Bhuvanaditya's son Karan has taken possession of the state. With the help of his wicked associates Haradas and Ratnadas, Karan captures Kanta and Tarala from the forest and tries to seduce them. Tarala yields to the temptation of becoming Karan's favorite queen, but Kanta does not give in. One night Tarala stealthily snaps Kanta's necklace in order to suggest that Sursen is dead. The next morning, Kanta leaves the palace for the cremation ground to commit sati.[1]

Meanwhile, Sursen, acting on the advice of his friend Haradas, strategically allows himself to be arrested, but leaves the prison when he senses Haradas's conspiracy against him, and goes to the forest where he laments the loss of his wife. When Haradas brings him back to the cremation ground, Kanta has already jumped in the funeral pyre. Seeing this, he also throws himself on the pyre. Tarala, after killing Karan, also ends her life in self-condemnation of her misdeed.[1]

Techniques and theme

Dwivedi employed the technique from Sanskrit drama of expressing the thoughts and emotions of characters through verse stanzas or songs, composed in various meters like soratha, doha, anushtup, harigit, indravijay, dindi, upajati and indravraja.[1] The acts of the play, its division of acts into scenes, its dialogues intermixed with verses and its depiction of several rasas, like the Shringara, Vira, Karuna and Bibhatsa (the Erotic, the Heroic, the Pathetic and the Repulsive, respectively), are in the style of Sanskrit drama. Its characterization, the inner conflicts of characters and the tragic end of the play are evidence of the influence of Shakespearean drama.[4] The depiction of Tarala's wavering mind when she stealthily proceeds to break Kanta's necklace resembles Macbeth's mental condition when proceeding to murder Duncan. The play ends like Hamlet, with several deaths.[1]

Reception and criticism

Kanta is widely considered to be a classic and the most outstanding play of the 19th-century in Gujarati literature.[2][5]

Ramanbhai Neelkanth described the play as 'one of the best specimens of objective poetry in Gujarati literature'[4] and as 'the only solace' in the dry land of Gujarati drama before 1909.[1] Mansukhlal Jhaveri appreciated some of its descriptions, particularly the inner conflict of Tarala when she was on her way to the bedroom of Kanta for cutting the necklace.[4] K. M. Jhaveri acclaimed the play, saying 'Dwivedi has displayed scholarship of no mean order in portraying human nature, in laying down the plot and in poetising the whole subject of the play.'[6] Dhirubhai Thaker, a scholar who has done extensive research on Dwivedi's work, appreciated the use of verses in the play with suitable dramatic effect. Thaker also pointed out some weaker aspects:

There are certain basic deficiencies of dramatic form in Kanta. The plot construction is loose. The dramatic device of a necklace as a symbol of Sursen's existence/devotion to his wife is not convincing. There is an inconsistency between certain actions and events of the play. The author has failed to set the dialogue in language appropriate to the characters concerned. Except for the Bhils, all the characters speak the author's language, which is sanskitised and pedantic with a tinge of charotari dialect (It may be said that Gujarati prose was not suitably cultivated for drama at that time). By and large, dialogues in Kanta are not brisk but dilatory.[1]

Thaker further added that, despite these deficiencies, Kanta occupies a prominent place in Gujarati dramatic literature by virtue of its form and poetic expression of sentiments.[1]

Performance

Kanta had moderate success on the stage.[2] The Mumbai Gujarati Natak Mandali inaugurated its theatrical activities by staging this play on 29 June 1889[7] under the title Kulin Kanta.[1][4] It was renamed by Dayashankar Visanji Bhatt after editing and modifying it to make it suitable for the stage.[8] As K. M. Jhaveri observes, 'it was a bold and a unique performance and shone like a gem when it was presented to the public. When it was staged in Mumbai, it proved a great success; the warmth of the sentiments, aided by suitable theatrical properties, kept the audience in a very happy mood from start to finish, and for several years Kanta played by the Mumbai Gujarati Natak Mandali continued to be "the rage" in Bombay'.[4]

References

- Thaker, Dhirubhai (1983). Manilal Dwivedi. Makers of Indian Literature. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. pp. 63–67. OCLC 10532609.

- George, K. M., ed. (1992). Modern Indian Literature, an Anthology: Surveys and Poems. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. p. 126. ISBN 978-81-7201-324-0.

- Dwivedi, Manilal. Kanta (Unknown ed.). p. 1.

- Jhaveri, Mansukhlal Maganlal (1978). History of Gujarati Literature. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. pp. 102–103. OCLC 462837743.

- Mehta, Chandravadan C. (1964). "Shakespeare and Gujarati Stage". Indian Literature. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. 7 (1): 44. JSTOR 23329678.

- Jhaveri, Krishnalal Mohanlal (1956). Further Milestones in Gujarati Literature (2nd ed.). Mumbai: Forbes Gujarati Sabha. p. 208. OCLC 569209571.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Choksi, Mahesh; Somani, Dhirendra, eds. (2004). ગુજરાતી રંગભૂમિ: રિદ્ધિ અને રોનક (Gujarati Rangbhoomi: Riddhi Ane Ronak) [Compilation of Information regarding professional theatre of Gujarat]. Ahmedabad: Gujarat Vishwakosh Trust. p. 103. OCLC 55679037.

- Baradi, Hasmukh (2003). History of Gujarati Theatre. Translated by Meghani, Vinod. New Delhi: National Book Trust, India. p. 47. ISBN 978-81-237-4032-4.

External links

- Kanta (play) at the Internet Archive