Kazuo Sakamaki

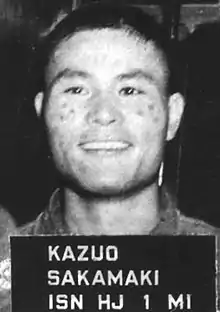

Kazuo Sakamaki (酒巻和男, Sakamaki Kazuo, November 8, 1918 – November 29, 1999) was a Japanese naval officer who became the first Japanese prisoner of war of World War II captured by U.S. forces.

Kazuo Sakamaki | |

|---|---|

Sakamaki in U.S. custody | |

| Born | November 8, 1918 Awa, Tokushima, Japan |

| Died | November 29, 1999 (aged 81) Toyota, Aichi, Japan |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1940–1941 |

| Rank | Ensign |

| Commands held | HA. 19 midget submarine |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Early life and education

Sakamaki was born in what is now part of the city of Awa, Tokushima Prefecture, one of eight sons. He was a graduate of the 68th class of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1940.

Career

Attack on Pearl Harbor

Ensign Sakamaki was one of ten sailors (five officers and five petty officers) selected to attack Pearl Harbor in five two-man Ko-hyoteki class midget submarines on 7 December 1941. Of the ten, nine were killed (including the other crewman in submarine HA. 19, CWO Kiyoshi Inagaki.) Sakamaki was chosen for the mission due to his large number of siblings.

After several attempts to enter Pearl Harbor, Sakamaki attempted to scuttle his disabled submarine, which had been trapped on a reef off Waimanalo Beach, Oahu. When the explosives failed to go off, he swam to the bottom of the submarine to investigate the cause of the failure and became unconscious due to a lack of oxygen. The book Attack on Pearl Harbor claims that his submarine hit four coral reefs and sank. Sakamaki was found by a U.S. soldier, David Akui, and was taken into military custody. When he awoke, he found himself in a hospital under U.S. armed guard. Sakamaki became the first Japanese prisoner of war in U.S. captivity during World War II and was stricken from Japanese records and officially ceased to exist. His submarine was captured intact and was subsequently taken on tours across the United States to encourage war bond purchases.[1][2]

After being taken to Sand Island, Sakamaki requested that he be allowed to kill himself, which was denied. Sakamaki spent the rest of the war in prisoner-of-war camps in the continental United States. At the war's end, he was repatriated to Japan, by which time he had become deeply committed to pacifism.[2]

Later life and death

After the war, Sakamaki worked with the Toyota Motor Corporation, becoming president of its Brazilian subsidiary in 1969. In 1983, he returned to Japan and continued working for Toyota before retiring in 1987. Outside of writing a memoir, Sakamaki refused to speak about the war until 1991, when he attended a historical conference at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas. He reportedly cried at the conference when he was reunited with his submarine (which was on display at the museum) for the first time in 50 years.[2]

He spent the rest of his life in Japan until his death in 1999 at the age of 81. He was survived by his wife and two children.[1]

References

- Goldstein, Richard (December 21, 1999). Kazuo Sakamaki, 81, Pacific P.O.W. No. 1. The New York Times.

- Burlingame, Burl (May 11, 2002). World War II's first Japanese prisoner shunned the spotlight. Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

Further reading

- Dorsey, James (July 1, 2010). "Literary Tropes, Rhetorical Looping, and the Nine Gods of War: 'Fascist Proclivities' Made Real". In Alan Tansman (ed.). The Culture of Japanese Fascism. Duke University Press. pp. 409–431. ISBN 978-0-8223-9070-1. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- Straus, Ulrich (October 1, 2011). The Anguish of Surrender: Japanese POWs of World War II. University of Washington Press. pp. 8–16. ISBN 978-0-295-80255-8. Retrieved November 19, 2016. Sakamaki's experience as a prisoner of war are detailed in the first chapter "Prisoner Number One"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kazuo Sakamaki. |