Kyōka

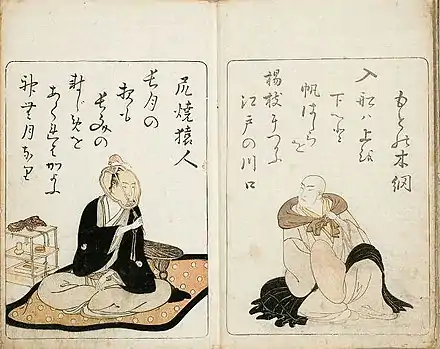

Kyōka (狂歌, "wild" or "mad poetry") is a popular, parodic subgenre of the tanka form of Japanese poetry with a metre of 5-7-5-7-7. The form flourished during the Edo period (17th–18th centuries) and reached its zenith during the Tenmei era (1781–89).[1]

Background

In much the way poets in the kanshi style (Chinese poetry by Japanese poets) wrote humorous kyōshi poems, poets in the native Japanese waka style composed humorous poems in the 31-syllable style.[1] Tanaka Rokuo suggests the style may have drawn inspiration from gishōka (戯笑歌, "playful and mocking verse"), poetry that targeted guests at banquets where they were read out in an atmosphere similar to that of a roast.[2]

During the Edo period (17th–19th centuries) there were two major branches of kyōka; one based in Edo (modern Tokyo), and Naniwa kyōka in the Kansai region.[1] Naniwa kyōka arose in Kyoto in the 16th century, at first practised by aristocrats such as Matsunaga Teitoku (1571–1654). It later found practitioners amongst commoners and centred in Osaka, whose earlier name Naniwa lent its name to the regional form.[1]

In the late 18th century, the economic policies of senior councillor Tanuma Okitsugu led to a sense of liberation, and various publishing forms flourished during this time. Edo samurai poets such as Yomo no Akara (1749–1823), Akera Kankō (1740–1800), and Karakoromo Kishū (1743–1802) gathered for meetings and contests of kyōka poetry, which they took to publishing in the following decade. The earliest and largest collection was the Manzai kyōka-shū (万載狂歌集, "Wild Poems of Ten Thousand Generations") that Akara edited and had published in 1783. Kyōka in Edo reached its zenith during the Tenmei era (1781–89).[1] The form attracted those from the various social classes, including low-level samurais, commoners such as merchants, and scholars of Chinese and Japanese classics.[2] Though its popularity spread to commoners, kyōka required considerable classical education and thus reached a limited audience; its popularity did not last into the modern era.[3]

Numerous kyōka poems appear throughout Jippensha Ikku's comic kokkeibon novel Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige (1802–22).[3]

Form

Kyōka poetry derives its form from the tanka, with a metre of 5-7-5-7-7.[4]

Most of the humour lies either in placing the vulgar or mundane in an elegant, poetic setting, or by treating a classical subject with common language or attitudes.[4] Puns, wordplay, and other word games were frequently employed—and make translation difficult. A common technique was honkadori (本歌取り), in which a classical poem was taken as a base (or honka 本歌) and altered to give it a vulgar twist.[3] Other common techniques include engo (intertextually associated words), kakekotoba (pivot words), and mitate (figurative language). The makurakotoba epithets common to waka are not used in kyōka.[2]

The following example demonstrates how Ki no Sadamaru (紀定丸, 1760–1841) used a well-known waka poem by the classical poet Saigyō (1118–1190) from the Shin Kokin Wakashū (1205) as a honka:[5]

| Saigyō's waka | Ki no Sadamaru's kyōka | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese text | Romanized Japanese[6] | English translation[6][lower-alpha 1] | Japanese text | Romanized Japanese[7] | English translation[7][lower-alpha 2] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the original, Saigyō had broken a branch from a cherry tree on Mount Yoshino in modern Nara to remind himself of a prime cherry-viewing spot; when he returns the next year, he chooses instead to go cherry-blossom viewing in an area he had not been to before. Ki no Sadamaru parodies the original by changing a few syllables, so that the poet finds himself wandering around, unable to find the branch he had broken.[5]

Notes

- Translation by Roku Tanaka, 2006

- Translation by Roku Tanaka, 2006

References

- Shirane 2013, p. 256.

- Tanaka 2006, p. 112.

- Shirane 2013, p. 257.

- Shirane 2013, pp. 256–257.

- Tanaka 2006, pp. 113–114.

- Tanaka 2006, p. 113.

- Tanaka 2006, p. 114.

Works cited

- Shirane, Haruo (2013). Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600–1900. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51614-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tanaka, Rokuo (2006). Davis, Jessica Milner (ed.). Understanding Humor in Japan. Wayne State University Press. pp. 111–126. ISBN 978-0-8143-4091-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)