Lactarius

Lactarius is a genus of mushroom-producing, ectomycorrhizal fungi, containing several edible species. The species of the genus, commonly known as milk-caps, are characterized by the milky fluid ("latex") they exude when cut or damaged. Like the closely related genus Russula, their flesh has a distinctive brittle consistency. It is a large genus with over 500 known species,[1] mainly distributed in the Northern hemisphere. Recently, the genus Lactifluus has been separated from Lactarius based on molecular phylogenetic evidence.

| Lactarius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lactarius vietus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Russulales |

| Family: | Russulaceae |

| Genus: | Lactarius Pers. (1797) |

| Diversity | |

| c. 583 species[1] | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

Systematics and taxonomy

The genus Lactarius was described by Christian Hendrik Persoon in 1797[3] with L. piperatus as the original type species. In 2011, L. torminosus was accepted as the new type of the genus after the splitting-off of Lactifluus as separate genus.[4][5][6]

The name "Lactarius" is derived from the Latin lac, "milk".

Placement within Russulaceae

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogenetic relationships of Lactarius, Lactifluus, Multifurca, and Russula according to Buyck et al. 2010.[7] |

Molecular phylogenetics uncovered that, while macromorphologically well-defined, milk-caps were in fact a paraphyletic genus; as a consequence, the genera Lactifluus was split from Lactarius, and the species L. furcatus was moved to the new genus Multifurca, together with some former Russula species.[4][7] Multifurca also represents the likely sister group of Lactarius (see phylogeny, right). In the course of these taxonomical rearrangements, the name Lactarius was conserved for the genus with the new type species Lactarius torminosus; this way, the name Lactarius could be retained for the bigger genus with many well-known temperate species, while the name Lactifluus has to be applied only to a smaller number of species, containing mainly tropical, but also some temperate milk-caps such as Lactifluus volemus and Lf. vellereus.[4][5][6]

Relationships within Lactarius

Phylogenetic analyses have also revealed that Lactarius, in the strict sense, contains some species with closed (angiocarpous) fruitbodies, e.g. L. angiocarpus described from Zambia.[8] The angiocarpous genera Arcangeliella and Zelleromyces are phylogenetically part of Lactarius.[8][9]

Systematics within Lactarius is a subject of ongoing research. Three subgenera are currently accepted and supported by molecular phylogenetics:[10]

- Piperites: Northern temperate region, three species in tropical Africa.

- Russularia: Northern temperate region and tropical Asia.

- Plinthogalus: Northern temperate region, tropical Africa, and tropical Asia.

Some more species, all tropical, do not seem to fall into these subgenera and occupy more basal positions within Lactarius.[9] This includes for example L. chromospermus from tropical Africa with an odd brown spore color.[9][11]

Currently, around 600 Lactarius species are described,[12] but roughly one fourth or 150 of these are believed to belong to Lactifluus,[13] while the angiocarpous genera Arcangeliella and Zelleromyces have not yet been synonymized with Lactarius. It is estimated that a significant number of Lactarius species remain to be described.[10]

Description

Macromorphology

_Fr_359776.jpg.webp)

The eponymous "milk" and the brittle consistency of the flesh are the most prominent field characters of milk-cap fruitbodies. The milk or latex emerging from bruised flesh is often white or cream, but more vividly coloured in some species; it can change upon exposition or remain unchanged. Fruitbodies are small to very large, gilled, rather fleshy, without veil, often depressed or even funnel-shaped with decurrent gills. Cap surface can be glabrous, velvety or pilose, dry, sticky or viscose and is often zonate. Several species have pits (scrobicules) on the cap or pileus surface. Dull colors prevail, but some more colorful species exist, e.g. the blue Lactarius indigo or the orange species of section Deliciosi. Spore print color is white to ocher or, in some cases, pinkish. Some species have angiocarpous, i.e., closed fruitbodies.[8]

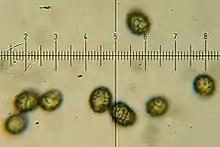

Micromorphology

Microscopically, Lactarius species have elliptical, rarely globoid spores with amyloid ornamentation in the form of more or less prominent warts or spines, connected by ridges, like other members of the family Russulaceae. The trama (flesh) contains spherical cells that cause the brittle structure. Unlike Russula, Lactarius also have lactiferous, i.e. latex-carrying hyphae in their trama.

Species identification

Distinguishing Lactarius from Lactifluus based on morphology alone is difficult; there are no synapomorphic characters known so far that define both genera unequivocally but tendencies exist:[10] zonate and viscose to glutinose caps are only found in Lactarius, as well as closed (angiocarpous) and sequestrate fruitbodies. All known annulate and pleurotoid (i.e., laterally stiped) milk-caps, on the contrary, belong to Lactifluus.

Characters important for identification of milk-caps (Lactarius and Lactifluus) are:[14][15][16] initial colour of the latex and color change, texture of cap surface, taste (mild, peppery, or bitter) of latex and flesh, odor, and microscopical features of the spores and the cap curticle (pileipellis). The habitat and especially the type of host tree can also be critical. While there are some easily recognizable species, other species can be quite hard to determine without microscopical examination.[16]

Distribution

Lactarius is one of the most prominent genera of mushroom-forming fungi in the Northern hemisphere. It also occurs natively in Northern Africa,[14] tropical Africa,[17] tropical Asia,[9][18] Central America,[19] and Australia.[20] Its possible native distribution in South America and different parts of Australasia is unclear, as many species in those regions, poorly known, might in fact belong to Lactifluus, which has a more tropical distribution than Lactarius.[13] Several species have also been introduced with their host trees outside their native range,[21] e.g. in South America,[22] Southern Africa,[17] Australia,[23] and New Zealand.[24]

Ecology

Lactarius belongs to a lineage of ectomycorrhiza obligate symbionts.[25] As such, they are dependent on the occurrence of possible host plants. Confirmed habitats apart from temperate forests include arctic tundra and boreal forest,[26] mediterranean maquis,[14][27][28] tropical African shrubland,[17] tropical Asian rainforest,[9][18] mesoamerican tropical oak forests,[19] and Australian Eucalyptus forests.[20]

While most species display a preference towards either broadleaf or coniferous hosts,[14][15] some are more strictly associated with certain genera or species of plant hosts. A well-studied example is that of alders, which have several specialized Lactarius symbionts (e.g. L. alpinus, L. brunneohepaticus, L. lilacinus), some of which even evolved specificity to one of the Alnus subgenera.[29] Other examples of specialized associations of Lactarius are with Cistus shrubs (L. cistophilus and L. tesquorum),[27][28] beech (e.g. L. blennius), birches (e.g. L. pubescens), hazel (e.g. L. pyrogalus), oak (e.g. L. quietus), pines (e.g. L. deliciosus), or fir (e.g. L. deterrimus). For most tropical species, host plant range is poorly known, but species in tropical Africa seem to be rather generalist.[17]

Lactarius species are considered late-stage colonizers, that means, they are generally not present in early-colonizing vegetation, but establish in later phases of succession.[30] However, species symbiotic with early colonizing trees, such as L. pubescens with birch, will rather occur in early stages.[31] Several species have preferences regarding soil pH and humidity,[14][15] which will determine the habitats in which they occur.

Edibility

Several Lactarius species are edible. L. deliciosus notably ranks among the most highly valued mushrooms in the Northern hemisphere, while opinions vary on the taste of other species, such as L. indigo or L. deterrimus. Several species are reported to be regularly collected for food in Russia, Tanzania and Hunan, China.[32] Some Lactarius are considered toxic, for example L. turpis, which contains a mutagenic compound,[33] or L. helvus. There are, however, no deadly poisonous mushrooms in the genus. Bitter or peppery species, for example L. torminosus, are generally not considered edible, at least raw, but are nevertheless consumed in some regions, e.g. in Finland.[34] Some small, fragrant species, such as the "candy caps", are sometimes used as flavoring.

L. deliciosus is one of the few ectomycorrhizal mushrooms that has been successfully cultivated.[35][36]

Chemistry

Different bioactive compounds have been isolated from Lactarius species, such as sesquiterpenoids,[37] aromatic volatiles,[38][39] and mutagenic substances.[33] Pigments have been isolated from colored Lactarius species, such as L. deliciosus[40] or L. indigo.[41]

A selection of well-known species

- Lactarius deliciosus - saffron milk-cap or red pine mushroom

- Lactarius deterrimus - false saffron milk-cap

- Lactarius indigo - indigo milk-cap

- Lactarius quietus - oak milk-cap

- Lactarius torminosus - woolly milk-cap

- Lactarius turpis - ugly milk-cap

- Lactarius trivialis - dark purple or creamy brown cap

See also

References

- Lee, Hyun; Wissitrassameewong, Komsit; Smythe, Jim; Myung Soo, Park; Verbeken, Annemieke; Eimes, John; Lim, Young Woon (2019-05-10). "Taxonomic revision of the genus Lactarius (Russulales, Basidiomycota) in Korea". Fungal Diversity. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

To date, 583 Lactarius species have been recorded globally

- "MycoBank: Lactarius". Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- Persoon CH. (1797). Tentamen dispositionis methodicae Fungorum (in Latin).

- Buyck B, Hofstetter V, Verbeken A, Walleyn R (2010). "Proposal to conserve Lactarius nom. cons. (Basidiomycota) with conserved type". Taxon. 59: 447–453. doi:10.1002/tax.591031.

- Barrie F. (2011). "Report of the General Committee: 11". Taxon. 60 (4): 1211–1214. doi:10.1002/tax.604026.

- Norvell LL. (2011). "Report of the Nomenclature Committee for Fungi: 16". Taxon. 60: 223–226. doi:10.1002/tax.601023.

- Buyck B, Hofstetter V, Eberhardt U, Verbeken A, Kauff F (2008). "Walking the thin line between Russula and Lactarius: the dilemma of Russula sect. Ochricompactae" (PDF). Fungal Diversity. 28: 15–40.

- Eberhardt U, Verbeken A (2004). "Sequestrate Lactarius species from tropical Africa: L. angiocarpus sp. nov. and L. dolichocaulis comb. nov". Mycological Research. 108 (Pt 9): 1042–1052. doi:10.1017/S0953756204000784. PMID 15506016.

- Verbeken A; Stubbe D; van de Putte K; Eberhardt U; Nuytinck J. (2014). "Tales of the unexpected: angiocarpous representatives of the Russulaceae in tropical South East Asia". Persoonia. 32: 13–24. doi:10.3767/003158514X679119. PMC 4150074. PMID 25264381.

- Verbeken A, Nuytinck J (2013). "Not every milkcap is a Lactarius" (PDF). Scripta Botanica Belgica. 51: 162–168.

- Buyck B, Verbeken A (1995). "Studies in tropical African Lactarius species, 2: Lactarius chromospermus Pegler". Mycotaxon. 56: 427–442.

- Kirk PM. "Species Fungorum (version September 2014). In: Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life". Retrieved 2014-09-27.

- "Contrasting evolutionary patterns in two sister genera of macrofungi: Lactarius and Lactifluus". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-09-27.

- Courtecuisse R, Duhem B (2013). Champignons de France et d'Europe. Guide Delachaux (in French). Paris: Delachaux & Niestlé. ISBN 978-2-603-02038-8.

- Eyssartier G, Roux P (2011). Le guide des champignons: France et Europe (in French). Paris: Editions Belin. ISBN 978-2-7011-5428-2.

- Kuo M. (2011). "MushroomExpert.com: The genus Lactarius". Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- Verbeken A, Buyck B (2002). Diversity and ecology of tropical ectomycorrhizal fungi in Africa. In: Tropical Mycology: Macromycetes (eds. Watling R, Frankland JC, Ainsworth AM, Isaac S, Robinson CH.) (PDF). pp. 11–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- Le HT, Stubbe D, Verbeken A, Nuytinck J, Lumyong S, Desjardin DE (2007). "Lactarius in Northern Thailand: 2. Lactarius subgenus Plinthogali" (PDF). Fungal Diversity. 27: 61–94.

- Halling RE, Mueller GM (2002). Agarics and boletes of neotropical oakwoods. In: Tropical Mycology: Macromycetes (eds. Watling R, Frankland JC, Ainsworth AM, Isaac S, Robinson CH.) (PDF). pp. 1–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- Miller OK Jr; Hilton RN. (1986). "New and interesting agarics from Western Australia" (PDF). Sydowia. 39: 126–137.

- Vellinga EC, Wolfe BE, Pringle A (2009). "Global patterns of ectomycorrhizal introductions". New Phytologist. 181 (4): 960–973. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02728.x. PMID 19170899.

- Sà MC, Baseia IG, Wartchow F (2013). "Checklist of Russulaceae from Brazil" (PDF). Mycotaxon: online 125: 303.

- Dunstan WA, Dell B, Malajczuk. (1998). "The diversity of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with introduced Pinus spp. in the Southern Hemisphere, with particular reference to Western Australia". Mycorrhiza. 8 (2): 71–79. doi:10.1007/s005720050215.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- McNabb RFR. (1971). "The Russulaceae of New Zealand 1. Lactarius DC ex S. F. Gray". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 9: 46–66. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1971.10430170.

- Rinaldi AC, Comandini O, Kuyper TW (2008). "Ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity: separating the wheat from the chaff" (PDF). Fungal Diversity. 33: 1–45.

- Geml J, Laursen GA, Timling I, McFarland JM, Booth MG, Lennon N, Nusbaum C, Tayler DL (2009). "Molecular phylogenetic biodiversity assessment of arctic and boreal ectomycorrhizal Lactarius Pers. (Russulales; Basidiomycota) in Alaska, based on soil and sporocarp DNA" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 18 (10): 2213–2227. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04192.x. PMID 19389163. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-10. Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- Comandini O, Contu M, Rinaldi AC (2006). "An overview of Cistus ectomycorrhizal fungi" (PDF). Mycorrhiza. 16 (6): 381–395. doi:10.1007/s00572-006-0047-8. PMID 16896800. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- Nuytinck J; Verbeken A; Rinaldi AC; Leonardi M; Pacioni G; Comandini O. (2004). "Characterization of Lactarius tesquorum ectomycorrhizae on Cistus sp. and molecular phylogeny of related European Lactarius taxa". Mycologia. 96 (2): 272–282. doi:10.2307/3762063. JSTOR 3762063. PMID 21148854.

- Rochet J, Moreau PA, Manzi S, Gardes M (2011). "Comparative phylogenies and host specialization in the alder ectomycorrhizal fungi Alnicola, Alpova and Lactarius (Basidiomycota) in Europe". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11: 40. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-40. PMC 3045908. PMID 21306639.

- Visser S. (1995). "Ectomycorrhizal fungal succession in jack pine stands following wildfire". New Phytologist. 129 (3): 389–401. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1995.tb04309.x.

- Twieg BD, Durall DM, Simard SW (2007). "Ectomycorrhizal fungal succession in mixed temperate forests". New Phytologist. 176 (2): 437–447. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02173.x. PMID 17888121.

- Härkonen M. (2002). Mushroom collecting in Tanzania and Hunan (Southern China): Inherited wisdom and folklore of two different cultures. In: Tropical Mycology: Macromycetes (eds. Watling R, Frankland JC, Ainsworth AM, Isaac S, Robinson CH.) (PDF). pp. 149–165. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- Suortti T, von Wright A, Koskinen A (1983). "Necatorin, a highly mutagenic compound from Lactarius necator". Phytochemistry. 22 (12): 2873–2874. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97723-9.

- Veteläinen M, Huldén M, Pehu T (2008). State of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture in Finland. Second Finnish National Report (PDF). Country Report on the State of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (Report). Sastamala, Finland: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. p. 14.

- Guerin-Laguette A.; Cummings N.; Butler R.C.; Willows A.; Hesom- Williams N.; Li S.; Wang Y. (2014). "Lactarius deliciosus and Pinus radiata in New Zealand: towards the development of innovative gourmet mushroom orchards". Mycorrhiza. 24 (7): 511–523. doi:10.1007/s00572-014-0570-y. PMID 24676792.

- "Edible Forest Fungi New Zealand". Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- Anke H, Bergendorff O, Sterner O (1989). "Assays of the biological activities of guaiane sesquiterpenoids isolated from the fruit bodies of edible Lactarius species". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 27 (6): 393–397. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(89)90145-2. PMID 2792969.

- Rapior S, Fons F, Bessière JM (2000). "The fenugreek odor of Lactarius helvus". Mycologia. 92 (2): 305–308. doi:10.2307/3761565. JSTOR 3761565.

- Wood WF; Brandes JA; Foy BD; Morgan CG; Mann TD; DeShazer DA. (2012). "The maple syrup odour of the "candy cap" mushroom, Lactarius fragilis var. rubidus". Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 43: 51–53. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2012.02.027.

- Yang XL, Luo DQ, Dong ZJ, Liu JK (2006). "Two new pigments from the fruiting bodies of the basidiomycete Lactarius deliciosus" (PDF). Helvetica Chimica Acta. 89 (5): 988–990. doi:10.1002/hlca.200690103. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-09-28.

- Harmon AD, Weisgraber KH, Weiss U (1979). "Preformed azulene pigments of Lactarius indigo (Schw.) Fries (Russulaceae, Basidiomycetes)". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 36: 54–56. doi:10.1007/BF02003967.

- Doljak, B.; Stegnar, M.; Urleb, U.; Kreft, S.; Umek, A.; Ciglarič, M.; Štrukelj, B.; Popovič, T. (2001). "Screening for selective thrombin inhibitors in mushrooms". Blood Coagulation and Fibrinolysis. 12 (2): 123–8. doi:10.1097/00001721-200103000-00006. PMID 11302474.

External links

- North American species of Lactarius by L. R. Hesler and Alexander H. Smith, 1979 (full text of monograph).