Lady in a Cage

Lady in a Cage is a 1964 American psychological thriller film directed by Walter Grauman, written and produced by Luther Davis,[2] and released by Paramount Pictures. It stars Olivia de Havilland, and features James Caan in his first substantial film role.

| Lady in a Cage | |

|---|---|

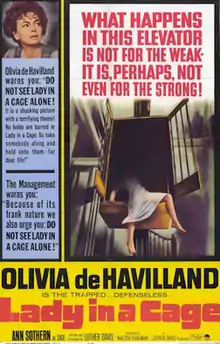

1964 Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Walter Grauman |

| Produced by | Luther Davis |

| Written by | Luther Davis |

| Starring | Olivia de Havilland James Caan |

| Music by | Paul Glass |

| Cinematography | Lee Garmes |

| Edited by | Leon Barsha |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1,650,000 (US/ Canada)[1] |

Plot

When an electrical power failure occurs, Mrs. Hilyard (Olivia de Havilland), a wealthy widow recuperating from a broken hip, becomes trapped between floors in the cage-like elevator she has installed in her mansion. With her son, Malcolm (William Swan), away for a summer weekend, she relies on the elevator's emergency alarm to attract attention, but the only response comes from an alcoholic derelict, George (Jeff Corey), who enters the home, ignores her pleas and steals some small items.

The wino sells the stolen goods to a fence, Mr. Paul, then visits his hustler friend, Sade (Ann Sothern), and tells her of the treasure trove he has stumbled upon. The expensive goods George fences attract the attention of three young hoodlums, Randall (James Caan), Elaine (Jennifer Billingsley) and Essie (Rafael Campos). They follow George and Sade back to the Hilyard home, where they conduct a violent orgy, ultimately killing George the wino and locking Sade in a closet.

Randall then pulls himself up to the elevator and taunts Hilyard, by suggesting that her son Malcolm might be gay. Randall shows her a letter that Malcolm left on her nightstand that morning, in which Malcolm threatens suicide because of her domineering manner. Shocked by the revelation, Hilyard faints. Shortly after, Paul (the fence) and his goons arrive to steal the goods from the hoodlums' car. After she regains consciousness, she falls from the elevator to the floor, hurting herself and crawls to ring the phone but does not realize the line was cut. She crawls to the front door just as Randall comes back through the back door. She yells for the police or anyone to help her and no one takes notice.

Randall follows her and, as he drags Hilyard back inside the house, she stabs him in the eyes with a pair of shivs she made from parts of the elevator. He finds his way back into the house, and commands his accomplices to bring her inside. Once in the doorway, Hilyard starts to mock Randall's blindedness and his cohorts join in, laughing at him, and leaving him to stumble through the living room, looking for a safe he cannot see. As they leave him, Hilyard mistakes Essie for Malcolm and speaks to him in a daze, ultimately feeling guilt over her monstrous hold on her son. She crawls out the front door again and Randall goes after her and in a struggle he stumbles onto the busy street and gets hit by a car. The melee of rushing vehicles come to a halt and several people finally come to the aid of Hilyard as Randall's head was crushed beneath a tire. Police arrive seconds later in response to the auto accident. People look on as she is in hysterics asking for them to arrest Essie and Elaine, who drive a car into her electric box, sparking the connection which resumes the electricity in the house. The surviving intruders are arrested, and Hilyard is sadly comforted.

Cast

- Olivia de Havilland as Mrs. Cornelia Hilyard

- James Caan as Randall Simpson O'Connell

- Jennifer Billingsley as Elaine

- Jeff Corey as George L. Brady Jr. aka Repent

- Ann Sothern as Sade

- Rafael Campos as Essie

- William Swan as Malcolm Hilyard

- Charles Seel as Mr. Paul (Junkyard Proprietor)

- Scatman Crothers as Junkyard Proprietor's Assistant

- Richard Kiel as Pawn shop strongman (uncredited)

- Ron Nyman as Neighbor (uncredited)

Production

The film is based on an original idea by Luther Davis, when he was working on a play about the effects of a power outage on the inhabitants of a house in oil country in the Midwest. That incident turned into a battle for survival, one in which Davis shifted the action in his story from a house to an elevator "since like so many New Yorkers I have a sense of claustrophobia in these little automatic elevators."[3]

Davis later said he was also inspired by the New York blackout of 17 August 1959. He knew a lady who was trapped in the elevator of a private residence on the city's Upper East Side. She called for help and was heard by two men who raped her.[4]

During his research, Davis learned that all elevators in New York have to be equipped with a phone, which would have ruined the story, so the film is set in an unnamed city.[3]

The film was announced in August 1962 with Ralph Nelson to direct and Robert Webber attached as star. Joan Crawford and Elizabeth Montgomery were being sought for the female lead.[5] Rosalind Russell was offered the part but turned it down.[6] In December 1962 Olivia de Havilland was announced as the star.[7] Her fee was $300,000.[8]

By February 1963 experienced TV director Walter Grauman signed to make his feature debut as a director.[9]

Filming took place in February 1963 at Paramount Studios. It took 14 days and de Havilland called the experience "wonderful" praising the talent of James Caan.[10]

Reception

Commercially, the film was profitable for Paramount.[11]

The film was initially received with negative reviews from critics who considered it to be vulgar and sub-par for an actress of de Havilland's stature. Bosley Crowther wrote a special column in the New York Times criticising the film, calling it "reprehensible"[12] which led to a press controversy.[13] Columnist Hedda Hopper wrote "The picture should be burned (...) Why did Olivia do it?"[14] Variety said that there is "not a single redeeming character or characteristic" in the "vulgar screenplay", criticizing de Havilland's performance as Oscar bait and Caan's as a copy of Marlon Brando.[15] Pittsburgh Post-Gazette also negatively compared Caan's performance to that of Brando and criticized the plot holes of the movie.[16]

Time mentioned that "[the film] adds Olivia de Havilland to the list of cinema actresses who would apparently rather be freaks than be forgotten".[17]

The film was re-evaluated decades later and it is now seen as a film that presented the turbulence and changes of society in the 1960s,[18] and a "deeply disturbing thriller".[19] TV Guide gave it 3 stars out of 5 and called it a "realistic, intense thriller".[20]

References

- "Big Rental Pictures of 1964", Variety, 6 January 1965 p 39. Please note this figure is rentals accruing to distributors not total gross.

- "Lady in a Cage". IMDb. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- MURRAY SCHUMACH (Mar 1, 1963). "'LADY IN A CAGE'. FILMING IS UNIQUE". New York Times. ProQuest 116597865.

- avis, L. (Jul 5, 1964). "'LADY IN CAGE'---SICK, Oregon DOES IT REFLECT SICKNESS OF OUR SOCIETY?". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 168649106.

- Scheuer, P. K. (Aug 16, 1962). "Boehm will direct 'electra' himself". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 168128613.

- Hopper, H. (Dec 3, 1962). "Entertainment". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 168295182.

- E. A. (Dec 4, 1962). "SCREENING IS SET FOR 'DR. CALIGARI'". New York Times. ProQuest 115800435.

- Hopper, H. (Sep 21, 1964). "Entertainment". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 155016704.

- Scheuer, P. K. (Feb 27, 1963). "New oil struck by old fox west coast". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 168285714.

- Hopper, H. (Mar 25, 1963). "Mankiewicz races deadline on 'cleo'". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 168235416.

- E. A. (Jul 2, 1964). "Paramount sees the big picture". New York Times. ProQuest 115837540.

- B. C. (Jun 21, 1964). "SOCIALLY HURTFUL". New York Times. ProQuest 115824765.

- Davis, L. (Jun 28, 1964). "Film on violent youth agitates reader". New York Times. ProQuest 115613577.

- Hopper, H. (Jun 20, 1964). "Entertainment". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 168600750.

- Lady in a Cage - Variety

- The New Film

- Olivia de Havilland: ‘Lady in a Cage’ (1964)

- Olivia de Havilland: ‘Lady in a Cage’ (1964)

- 'Lady in a Cage': still lurid after a half-century

- Lady in A Cage - Movie Reviews