Lake Ilopango

Lake Ilopango is a crater lake which fills an 8 by 11 km (72 km2 or 28 sq mi) volcanic caldera in central El Salvador, on the borders of the San Salvador, La Paz, and Cuscatlán departments.[1] The caldera, which contains the second largest lake in the country and is immediately east of the capital city, San Salvador, has a scalloped 100 m (330 ft) to 500 m (1,600 ft) high rim.[2] Any surplus drains via the Jiboa River to the Pacific Ocean. An eruption of the Ilopango volcano is considered a possible source for the extreme weather events of 535–536. The local military airbase, Ilopango International Airport, has annual airshows where international pilots from all over the world fly over San Salvador City and Ilopango lake.

| Lake Ilopango | |

|---|---|

Westward view from lake Ilopango, aft San Salvador Metropolitan Area and San Salvador (volcano) lie just ahead | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 450 m (1,480 ft) |

| Coordinates | 13.67°N 89.05°W |

| Geography | |

Lake Ilopango Location in El Salvador | |

| Location | El Salvador |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Caldera |

| Last eruption | 1879 to 1880 |

| Lake Ilopango | |

|---|---|

Eastward view from San Salvador (volcano), San Salvador Metropolitan Area at the center and aft, the ilopango caldera lies just behind along with San Vicente (volcano) | |

Lake Ilopango | |

| Location | Central El Salvador |

| Coordinates | 13.67°N 89.05°W |

| Type | crater lake |

| Basin countries | El Salvador |

| Max. length | 11 km (6.8 mi) |

| Max. width | 8 km (5.0 mi) |

| Surface area | 72 km2 (28 sq mi) |

| Max. depth | 230 m (750 ft) |

| Surface elevation | 440 m (1,440 ft) |

| Islands | Islas Quemadas |

Eruptive history

.jpg.webp)

Four major dacitic–rhyolitic eruptions occurred during the late Pleistocene and Holocene, producing pyroclastic flows and tephra that blanketed much of the country.[2]

The caldera collapsed most recently[2] sometime between 410 and 535 AD (based on radiocarbon dating of plant life directly related to the eruption),[3] which produced widespread pyroclastic flows and devastated Mayan cities; however, a team of scientists concluded that the volcanic eruption might have happened in 431 AD ±2, based on volcanic shards taken from ice cores in Greenland, levels of sulphur recorded in ice cores from Antarctica, and radiocarbon dating of a charred tree found in volcanic ash deposits.[4] The eruption produced about 84 km3 (20 cu mi)[5] of tephra (several times as much as the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens), thus rating a 6 on the (VEI) Volcanic Explosivity Index. The "ash-cloud fallout ... blanketed an area of at least 10,000 square kilometers waist-deep in pumice and ash", which would have stopped all agricultural endeavor in the area for decades. It is also theorized that the eruption and subsequent weather events and agricultural failures directly led to the abandonment of Teotihuacan by the original inhabitants.[6] Other researchers estimated that in its sixth-century eruption, Ilopango expelled the equivalent of 10.5 cubic miles of dense rock, making it one of the biggest volcanic events on Earth in the last 7,000 years.[7]

It was hypothesized that this eruption caused the extreme weather events of 535–536 in Europe and Asia, but this is unlikely given the research published in 2020 that dates the eruption to 431 AD.[4]

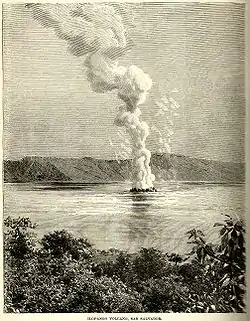

Later eruptions formed several lava domes within the lake and near its shore. The only historical eruption, which occurred from December 31, 1879, up to March 26, 1880, produced a lava dome and had a VEI of 3.[2] The lava dome reached the surface of the lake, forming the islets known as Islas Quemadas.[8][9]

See also

References

- "Lake Ilopango". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- "Ilopango: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- Dull, Robert A.; Southon, John R.; Sheets, Payson (2001). "Volcanism, Ecology and Culture: A Reassessment of the Volcan Ilopango Tbj eruption in the Southern Maya Realm". Latin American Antiquity. Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 12, No. 1. 12 (1): 25–44. doi:10.2307/971755. JSTOR 971755., esp. p.27.

- Victoria C. Smith; et al. (2020). "The magnitude and impact of the 431 CE Tierra Blanca Joven eruption of Ilopango, El Salvador". PNAS. doi:10.1073/pnas.2003008117.

- "Extreme weather events of 535–536", Wikipedia, 2019-05-22, retrieved 2019-07-07

- Clive Oppenheimer (2011). Eruptions that shook the world. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64112-8.

- Greshko, M. Colossal volcano behind 'mystery' global cooling finally found. National Geographic. 23 August 2019.

- Golombek, Matthew P.; Carr, Michael J. (1978). "Tidal triggering of seismic and volcanic phenomena during the 1879–1880 eruption of Islas Quemadas volcano in El Salvador, Central America". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 3 (3–4): 299–307. Bibcode:1978JVGR....3..299G. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(78)90040-9.

- "Historia y cultura de Ilopango". Elsalvadorenelmundo.com. Archived from the original on 2014-02-04. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ilopango Caldera. |