Lake Maracaibo

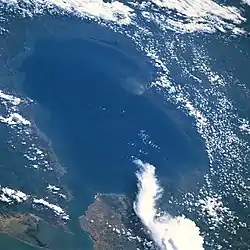

Lake Maracaibo (Spanish: Lago de Maracaibo, pronounced [ˈlaɣo ðe maɾaˈkajβo] (![]() listen)) is a large brackish tidal bay (or tidal estuary) in Venezuela and an "inlet of the Caribbean Sea".[1][2][3][4] It is sometimes considered a lake rather than a bay or lagoon.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] It is connected to the Gulf of Venezuela by Tablazo Strait, which is 5.5 kilometres (3.4 mi) wide at the northern end. It is fed by numerous rivers, the largest being the Catatumbo. At 13,210 square kilometres (5,100 sq mi) it was once the largest lake in South America; the geological record shows that it was a true lake in the past, and as such is one of the oldest lakes on Earth at 20–36 million years old.[14][15]

listen)) is a large brackish tidal bay (or tidal estuary) in Venezuela and an "inlet of the Caribbean Sea".[1][2][3][4] It is sometimes considered a lake rather than a bay or lagoon.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] It is connected to the Gulf of Venezuela by Tablazo Strait, which is 5.5 kilometres (3.4 mi) wide at the northern end. It is fed by numerous rivers, the largest being the Catatumbo. At 13,210 square kilometres (5,100 sq mi) it was once the largest lake in South America; the geological record shows that it was a true lake in the past, and as such is one of the oldest lakes on Earth at 20–36 million years old.[14][15]

| Lake Maracaibo | |

|---|---|

| |

.jpg.webp) Lake Maracaibo | |

Map | |

| Coordinates | 09°48′57″N 71°33′24″W |

| Type | Ancient lake, Coastal saltwater, bay |

| Primary inflows | Catatumbo River |

| Primary outflows | Gulf of Venezuela |

| Basin countries | Venezuela |

| Max. length | 99 miles (159 km) |

| Max. width | 67 miles (108 km) |

| Surface area | 13,210 km2 (5,100 sq mi) |

| Max. depth | 60 m (200 ft) |

| Water volume | 280 km3 (230,000,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Surface elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Islands | 467 |

| Settlements | Maracaibo, Cabimas, Ciudad Ojeda |

Lake Maracaibo acts as a major shipping route to the ports of Maracaibo and Cabimas. The surrounding Maracaibo Basin contains large reserves of crude oil, making the lake a major profit center for Venezuela.[15][16] The basin also holds almost a quarter of Venezuela's population.[17] A dredged channel gives oceangoing vessels access to the bay. The 8.7-kilometre (5.4 mi) long General En Jefe Rafael Urdaneta Bridge, which was completed in 1962 and spans the bay's outlet, is one of the longest bridges in the world.

The weather phenomenon known as the Catatumbo lightning at Lake Maracaibo regularly produces more lightning than any other place on the planet.[18][19]

The villages of Barranquitas and San Luis, on the lake's western shore, have the highest concentration of Huntington's disease sufferers in the world.[20][21][22]

History

The first known settlements on the bay were those of the Guajiros, who still are present in large numbers, but were re-settled in the western boundary area with Colombia. The first European to discover the bay was Alonso de Ojeda on August 24, 1499, on a voyage with Amerigo Vespucci (the same explorer for whom the American continents were named).

Legend has it that upon entering the lake, Ojeda's expedition found groups of indigenous huts, built over stilts on water (Spanish: palafitos), and interconnected by boardwalks on stilts, with each other and with the lake shore. The stilt houses reminded Vespucci of the city of Venice, (Spanish: Venecia, Italian: Venezia), so he named the region "Venezuela,"[23] meaning "little Venice" in Spanish.[24] The suffix -uela is used as a diminutive term (e.g., plaza / plazuela, cazo / cazuela); some have argued that the suffix was also intended to be pejorative.[25] (Examples of palafitos can still be found in "Santa Rosa", an area in the city of Maracaibo.)

Although the Vespucci story remains the most popular and accepted version of the origin of the country's name, a different reason for the name comes up in the account of Martín Fernández de Enciso, a member of the Vespucci and Ojeda crew. In his work Summa de Geografía, he states that they found an indigenous population who called themselves the "Veneciuela," which suggests that the name "Venezuela" may have evolved from the native word.[26]

The port town of Maracaibo was founded in 1529 on the western side. In July 1823, the bay was the site of the Battle of Lake Maracaibo, an important battle in the Venezuelan War of Independence. Oil production began in the surrounding basin in 1914, with wells drilled by Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij, a predecessor of Royal Dutch Shell.

On April 6, 1964, at 11:45 pm, the tanker Esso Maracaibo, loaded with 236,000 barrels (37,500 m3) of crude oil, suffered a major electrical failure, so that control of steering was lost. Thus it collided with pier #31 of the two-year-old General Rafael Urdaneta Bridge across the mouth of the lake. A 259 metres (850 ft) section of the bridge roadway fell into the water with a portion coming to rest across the tanker just a few feet from the ship's superstructure. No oil spill occurred, and there were no deaths or serious injuries on the tanker. However, seven motorists and passengers in vehicles crossing the bridge were killed.

Islands

Some of the islands within the lake are of considerable size. They are populated with fishermen and are used for commercial and recreational purposes. The majority of the islands are located in the Almirante Padilla municipality, including:

- Zapara Island

- Toas Island

- San Carlos Island

- Isla de Providencia

- Isla de Pescadores

- Los Pájaros Island

- Maraca Island

- San Bernardo Island

- Sabaneta de Montiel Island

Fishing

As recently as 2000, Lake Maracaibo supported 20,000 fishermen.[27]

Settlements

Several settlements built out on stilts over the lake – palafitos – still exist in the south and south-west, notably at Lagunetas.

Subsiding ground

Due to the massive volume of oil removed in the Maracaibo Basin, some oil-producing areas adjacent to Lake Maracaibo have sunk, changing the geography of the region. The original concessions to oil companies purposefully assigned swamps and wetlands along the east border of the lakes for facilities. This required the oil companies to build dikes and drain the land in order to build their facilities; Dutch Shell takes credit for some of the most enduring dike systems. Since the nationalization of the oil industry in 1976, maintenance of the dike systems has fallen upon the Venezuelan government to protect sub-sea-level areas like Tía Juana, Lagunillas, and Bachaquero from encroachment by the waters. Cumulative subsidence is as much as 5 metres (16 ft), and it continues at a rate of up to 20 centimetres per year (7.9 in/year) at some locations inland and typically 5 cm/year (2.0 in/year) along the coast. Due to the negligence of maintenance to the dike, many consider it to be a disaster in waiting, with the potential of an earthquake causing soil liquefaction and submerging a large population. A program of mitigative measures to address the seismic risk was begun in 1988. Ongoing maintenance and improvements to the dike will be needed, as it continues to subside by as much as 7 cm/year (2.8 in/year).[28]

Duckweed infestation

As of June 18, 2004, a large portion (18%) of the surface of Lake Maracaibo is covered by duckweed, specifically Lemna. Although efforts to remove the plant have been underway, the plant – which can double its size every 48 hours – occupies over 130 million cubic meters of the lake. The only way to remove the weed is to pull it out of the lake physically – no chemical or biological method has been found to treat the weed. The government has been spending $2 million monthly to clean the lake, and the state-run oil company Petroleos de Venezuela S.A. has created a $750 million cleanup fund. Current efforts are barely keeping up with the growth of the plant. The removal process has proven to be particularly difficult in the center of the lake, where a specially equipped ship may be needed to pull the weed off the lake.

There is some mystery as to how the plant came to reside in the waters of Lake Maracaibo. According to scientists from the Institute for the Conservation of Lake Maracaibo (ICLAM), one of the government organizations charged with the care of Lake Maracaibo, the weed is probably native to the lake, but few studies have been conducted to confirm that suspicion. The prodigious growth of the freshwater-marine plant is likely a self-purification mechanism. Others disagree, believing the type of duckweed to be native to Florida and Texas and thus the infestation is a result of its having been transported by ship.

Another point of uncertainty is why the scale of the outbreak is so great. Maracaibo is fed by both salt water from the Caribbean and fresh water from numerous rivers. The lighter fresh water floats on top of the heavier salt water, which forms a dense layer on the bottom. This set-up traps nutrients that have settled on the floor of the lake. In the spring of 2004, heavy rains disrupted the usual pattern. The sudden influx of fresh water stirred the layers, allowing nutrients to float to the top, where duckweed and other plants reside. These nutrients may have triggered the duckweed's rapid expansion. Additional sources of nutrients include untreated sewage discharge and fertilizers and other industrial waste flowing into the lake through rivers (97 percent of the country's raw sewage is discharged without treatment into the environment). Furthermore, chemicals used to clean up oil spills may have contributed to the duckweed problem. The lake basin hosts Venezuela's largest oil fields, and high concentrations of biodegradable dispersants that contain phosphates and polyaspartic acid – a chemical used to increase nutrient uptake in crops – have been found, a veritable feast for the plants. Scientists at ICLAM disagree, saying that dispersants have been banned from the lake for years and, even if they were present, could not contain enough nutrients to support the current duckweed population.

Duckweed is not toxic to fish, but some scientists are concerned that it could deplete oxygen levels in the lake as it decays, asphyxiating large numbers of fish. Though officials say the weed hasn't harmed fish yet, it is putting a dent in the local fishing industry. The plant clogs the motors of small boats, making it impossible for fishers to launch their vessels. Duckweed further threatens the local ecosystem by choking out other plants as it shades large portions of the lake. In certain conditions, the weed may concentrate heavy metals and bacteria such as Salmonella and Vibrio cholerae, the bacterium that causes cholera. Despite these problems, the weed may yet have some positive use; duckweed can be treated to be fed to poultry or to make paper.

As of 2017, the last duckweed infestation was in 2010.[29]

See also

- Costa Oriental del Lago, a subregion and conurbation of 700,000 inhabitants located on the eastern side of the lake.

- Sur del Lago, a subregion located in the southern part of the lake

Notes

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (16 June 2016). "Lake Maracaibo". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Merriam-Webster (2016). Webster's New Geographical Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. p. 727. ISBN 978-0-87779-446-2.

- Times Books (2014). Comprehensive Atlas of the World. HarperCollins. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-00-755140-8.

- Question Unlimited (2003). "Who Wants to Be a Judge at the National Academic Championship?". National Academic Championship. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- John C. Murphy (2012). "Marine Invasions by Non-Sea Snakes, with Thoughts on Terrestrial–Aquatic–Marine Transitions". Integr. Comp. Biol. Oxford Journals Volume 52, Issue 2 Pp. 217-226. 52 (2): 217–226. doi:10.1093/icb/ics060. PMID 22576813. Retrieved May 10, 2012.

...from Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela. The mostly freshwater lake is a remnant of the Orinoco changing course, and has a direct flow of water from the Caribbean through the Strait of Maracaibo and Tablazo Bay.

- "Earth's New Lightning Capital Revealed". NASA. 2016-05-02.

Buechler noted that Lake Maracaibo is not new to lightning researchers. Located in northwest Venezuela along part of the Andes Mountains, it is the largest lake in South America. Storms commonly form there at night as mountain breezes develop and converge over the warm, moist air over the lake.

- Wayne S. Gardner and Joann F. Cavaletto (1998). "Nitrogen cycling rates and light effects in tropical Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela" (PDF). Limnol. Oceanogr. American Society of Limnology. 43 (8): 1814–1825. Bibcode:1998LimOc..43.1814G. doi:10.4319/lo.1998.43.8.1814. hdl:2027.42/109860.

Some features of tropical lakes resemble those of temperate lakes in summer...Information on nutrient cycling from temperate lakes cannot necessarily be extrapolated to tropical lakes, because of the fundamental differences in the physical and biological dynamics of the two types of systems.

- John P. Rafferty (1 October 2010). Lakes and Wetlands: A "Juvenile Nonfiction Book". Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-61530-403-5.

- Joyce A. Quinn; Susan L. Woodward (3 February 2015). Earth's Landscape: An Encyclopedia of the World's Geographic Features [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of the World's Geographic Features. ABC-CLIO. p. 397. ISBN 978-1-61069-446-9.

- DEME: Lake Maracaibo Archived 2009-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- The Compass of Sigma Gamma Epsilon (1939:184)

- Ralph Alexander Liddle (1946:24) The Geology of Venezuela and Trinidad

- Kenneth Knight Landes (1951:535) Petroleum Geology

- Lake Profile: Maracaibo. LakeNet.

- Maracaibo, Lake Archived 2006-12-21 at the Wayback Machine. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition.

- Boschetti, Tiziano; Angulo, Beatriz; Cabrera, Frank; Vásquez, Jhaisson; Montero, Ramón Luis (2016). "Hydrogeochemical characterization of oilfield waters from southeast Maracaibo Basin (Venezuela): Diagenetic effects on chemical and isotopic composition". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 73: 228–248. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2016.02.020.

- "LakeNet - Lakes". www.worldlakes.org.

- Baverstock, Alasdair (11 March 2015). "Venezuela's nightly lightning show". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- Albrecht, R. I.; Goodman, S. J.; Buechler, D. E.; Blakeslee, R. J.; Christian, H. J. (2016). "Where are the lightning hotspots on Earth?". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 97 (11): 2051–2068. Bibcode:2016BAMS...97.2051A. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-14-00193.1.

- "HDF In Venezuela". Hereditary Disease Foundation. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Mohammadi, Dara (2016-05-15). "Huntington's disease: the new gene therapy that sufferers cannot afford". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- "Searching for a cure for Huntington's disease". BBC News. 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Dydyński, Krzysztof; Beech, Charlotte (2004). Venezuela. Lonely Planet. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-74104-197-2. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- Thomas, Hugh (2005). Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire, from Columbus to Magellan. Random House. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-375-50204-0.

- Jáuregui, José Antonio (2004). España vertebrada. p. 72. ISBN 978-8496326019.

En 1499 Alonso de Ojeda vio un pueblecito de indios levantado sobre estacas en medio de las aguas y lo llamó Venezuela, la pequeña Venecia (-uelo y -uela son diminutivos españoles que proceden de -ulum y -ula, diminutivos del idioma de Roma, «madre patria» de los españoles, británicos, franceses y europeos].

- "Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos" (in Spanish). Instituto de Cultura Hispánica (Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional). 1958: 386. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - www.bloomberg.com https://www.bloomberg.com/businessweek/2000/00_51/c3712238.htm. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Juan Murria, "Subsidence Due to Oil Production in Western Venezuela: Engineering Problems and Solutions," Land Subsidence (Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Land Subsidence, May 1991). IAHS Publ. no. 200, 1991.

- "Lake Maracaibo: an announced environmental disaster". Earth Starts Beating. 2017-05-18. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

References

- "Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 2006-10-01. Retrieved 2006-05-24.