Leopard complex

The leopard complex is a group of genetically related coat patterns in horses. These patterns range from progressive increases in interspersed white hair similar to graying or roan to distinctive, Dalmatian-like leopard spots on a white coat. Secondary characteristics associated with the leopard complex include a white sclera around the eye, striped hooves and mottled skin. The leopard complex gene is also linked to abnormalities in the eyes and vision. These patterns are most closely identified with the Appaloosa and Knabstrupper breeds, though its presence in breeds from Asia to western Europe has indicated that it is due to a very ancient mutation.

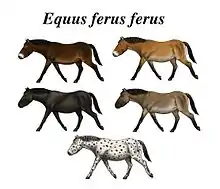

.jpg.webp)

Leopard complex patterns

Coat patterns in the leopard complex range from being hardly distinguishable from an unaffected coat, to nearly pure white. Unlike most other spotting patterns, the spotting and especially the white regions associated with the leopard complex tend to be symmetrical and originate over the hips.[1] Furthermore, a certain amount of this inherited white patterning is present at birth.[2] The amount of white, even if none is present at birth, often grows throughout the horse's life by gradual "roaning" which is not related to graying or true roan.[2] Colored spots reflect the underlying coat color, be it black, chestnut, gray, or silver dun-buckskin.[3] A number of factors, each separately, genetically controlled, interact to produce familiar patterns such as "snowflake," "leopard," and "fewspot".

Leopard spotting

A single, incomplete dominant gene (Lp) controls the presence of leopard-spotting in horses.[4][5] A dominant gene requires only a single copy to produce an affected phenotype; an incomplete dominant gene produces a different result depending on whether one or two copies are present. A horse's genotype may be lp/lp (homozygous recessive), Lp/lp (heterozygous), or Lp/Lp (homozygous dominant). Horses without a dominant Lp gene do not exhibit leopard-complex traits, and cannot produce offspring with the Lp gene unless it is contributed by the other parent. Such horses are termed "non-characteristic" among Appaloosa horse aficionados.[6] Horses with at least one Lp gene possess, at the very least, leopard-complex "characteristics":

- skin that is mottled, speckled or blotchy around the muzzle, eyes, genitals, and anus; the remainder of the body may be primarily pigmented (gray or black in the absence of other genes), primarily unpigmented (pink or flesh-colored), or mottled,

- striped hooves,

- white sclera.

The presence of regions of alternating pigmented and unpigmented skin may not definitively suggest the leopard gene. They may not be visible due to the effects of other genes. For example, extensive white markings on the face may mask the presence of mottling around the eyes and muzzle, and white markings on the legs often end in white hooves. Furthermore, other genes may produce similar conditions: white sclera are associated with broad white face markings, striped hooves with the Silver dapple gene, and freckled skin with the Champagne gene. A DNA test can now identify the Lp gene, though a combination of pedigree knowledge and coat characteristics also help.

While both heterozygous and homozygous Lp horses possess the aforementioned characteristics, heterozygotes and homozygotes differ significantly in the presence of true spots. True leopard spots are produced only by the Lp gene, and directly reflect the underlying coat color (bay, black, gray, cremello, red dun, and so on).[3] Since these spots match the coat color, they are not visible unless the surrounding pigment is removed. As a rule, heterozygous leopards have larger, more abundant spots, while homozygotes have smaller, scarcer spots.[5]

White patterning

There is at least one genetically controlled type of white patterning that is strictly associated with the leopard complex.[2] These white patterns permit the spots associated with the leopard complex to become visible. Other white patterns, such as tobiano or white leg markings, obscure leopard spots. A certain amount of leopard-associated white patterning may be present at birth. Temporal changes in the amount of white patterning are discussed below.[7] Leopard-associated white patterning is usually symmetrical and originates over the hips.[1] A proposed gene, PATN-1, may be responsible for the most familiar expressions of white: heterozygotes possessing common-size "blankets" and homozygotes possessing extensive "blankets" that may affect the entire coat.[2] Even horses with extensive white usually retain dark colored regions just above the hooves, on the knees and hocks, stifles and elbows, hips and points of shoulder, the tail, mane, and the bony parts of the face. The smallest amount of white patterning is just a sprinkling of white over the hips.

Leopard-associated roaning

Just as there is white patterning specifically associated with the leopard complex, there is a type of progressive roaning that is unrelated to graying out or true roan.[2] Horses with coat patterns within the leopard complex are known for their mystifying coat changes.[8] This unusual characteristic is due at least in part to leopard roaning, also called "varnish roaning." While the gray gene only affects the hair, some horses with the Lp gene will progressively lose pigment in both the skin and hair as they age. Also unlike graying out, the leopard spots are not affected by this roaning process. Neither are the "bony prominences" strongly affected. As a varnish roan horse lightens, the leopard spots indistinguishable from the rest of the coat become visible. Some horses without any dense white patterning at birth seem to spontaneously develop into white, leopard-spotted horses with maturity.[8] Varnishing is more common among Appaloosa horses, and less common among Norikers and Knabstruppers, whose breed associations find it undesirable.[5]

Interactions and terminology

Like much of coat color genetics, commonly used terms do not necessarily correspond to precise genetic states. Nevertheless, terminology can reveal a lot about the genetic interactions surrounding the leopard complex.

- Heterozygous Lp/lp horses with extensive white patterning at birth are white with large, self-colored spots. They are termed "leopard" if fully white, "near-leopard" if not. By the action of varnish roan, a near-leopard may in time become nearly indistinguishable from a full leopard.

- Heterozygous Lp/lp horses with less white patterning are described by the size of their "blanket" and the presence of spots: spotted blanket over loin and hips, for example. Again, these horses may varnish with age.

- Homozygous Lp/Lp horses with extensive white patterning at birth are white with tiny, sparse spots or none at all. In most languages, such foals are called "white-born" but the term familiar to most English speakers is "fewspot (leopard)."

- Homozygous Lp/Lp horses with less than extensive white patterning at birth possess dense white blankets and are called "snowcap."

- Heterozygous Lp/lp and homozygous Lp/Lp horses with only a tiny amount of white patterning may not possess enough white to reveal large or small spots. A sprinkling of white patterning over the hips is called a "snowflake" pattern. Such tiny blankets may varnish and grow.

- Heterozygous Lp/lp horses and homozygous Lp/Lp horses, in the absence of dense white patterning, appear much the same. That is, unless they begin to varnish. As the coat becomes more and more white, spots may become visible. A homozygous Lp/Lp horse, with only tiny spots, may simply develop this unique roaning pattern and is called "frosted" or "marble." A heterozygote may eventually show conspicuous leopard spots.

Patterns

Base colors are overlain by various spotting patterns, which are variable and often do not fit neatly into a specific category. These patterns are described as follows:

| Pattern | Description | Image[9] |

| Blanket or snowcap | A solid white area normally covering, but not limited to, the hip area, with a contrasting base color.[10][11] |  |

| Spots | Generic term for a horse which has white or dark spots over all or a portion of its body.[10] | .jpg.webp) |

| Blanket with spots | a white blanket which has dark spots within the white. The spots are usually the same color as the horse's base color.[10] |  |

| Leopard | Considered an extension of a blanket to cover the whole body. A white horse with dark spots that flow out over the entire body.[11] |  |

| Few Spot Leopard | A mostly white horse with a bit of color remaining around the flank, neck and head.[11] |  |

| Snowflake | A horse with white spots, flecks, on a dark body. Typically the white spots increase in number and size as the horse ages.[11] | .jpg.webp) |

| Appaloosa Roan, Varnish roan or Marble | A distinct version of the leopard complex. Intermixed dark and light hairs with lighter colored area on the forehead, jowls and frontal bones of the face, over the back, loin and hips. Darker areas may appear along the edges of the frontal bones of the face as well and also on the legs, stifle, above the eye, point of the hip and behind the elbow. The dark points over bony areas are called "varnish marks" and distinguish this pattern from a traditional roan.[10][11] |  |

| Mottled | A fewspot leopard that is completely white with only mottled skin showing.[11] |  |

| Roan Blanket or Frost | Horses with roaning over the croup and hips. The blanket normally occurs over, but is not limited to, the hip area.[10][11] |  |

| Roan Blanket With Spots | refers to a horse with a roan blanket which has white and/or dark spots within the roan area.[10] |  |

The Lp gene

Although the spotting and roaning patterns that make up the leopard complex sometimes appear very different from each other, the ability of leopard-spotted horses to produce the full spectrum of patterns, from mottled skin to roaning to more leopard-spotted offspring, has long suggested that a single gene was responsible.[5] This gene was termed Lp for "leopard complex" by Dr. D. Phillip Sponenberg in 1982, and was described as an autosomal, incomplete dominant gene.[4] Horses without the gene (lplp) were solid-colored, those with two copies of the gene (homozygous or LpLp) were usually "fewspots", while those with a single copy of the gene (heterozygous or Lplp) ranged from mere mottled skin to full leopard.[4]

In 2004, Lp was assigned to equine chromosome 1 (ECA1) by a team of researchers.[1] Four years later, this team mapped the Lp gene to a transient receptor potential channel gene, TRPM1 or Melastatin 1 (MLSN1).[7] The leopard complex allele contains a 1378 bp long terminal repeat insertion of retroviral DNA which disrupts transcription of TRMP1.[13]

In 2011, a study identified the Lp allele in DNA samples collected from prehistoric horses. This finding represents evidence for the presence of leopard complex spotting in prehistoric wild horse populations. The ancient origin of the allele may explain the presence of spotted horse paintings in paleolithic cave art. It is thought that during the ice age the leopard pattern may have been helpful as camouflage against the snowy environment.[12]

Vision issues

Congenital stationary night blindness is an ophthalmologic disorder in horses which is present at birth (congenital), non-progressive (stationary) and affects the animal's vision in conditions of low lighting. Horses with CSNB may be hesitant to enter dimly-lit places - such as indoor arenas, dark stalls, or trailers - and be apprehensive when in such conditions, which may interfere with handling or riding.[7] CSNB is usually diagnosed based on the owner's observations, but some horses have visibly abnormal eyes: poorly aligned eyes (dorsomedial strabismus) or involuntary eye movement (nystagmus).[7] The condition can be confirmed using electroretinography, from which a "negative ERG" indicates CSNB. While the retina is a normal shape, the nerve signal triggered when light reaches rod cells does not reach the brain. Rod cells in the retina are connected to bipolar cells, which transmit the nerve impulse to the next set of neurons. It is thought that these cells fail to undergo the basic chemical reaction for nerve impulse transmission, which involves shuttling of calcium (Ca2+).

Congenital stationary night blindness has been linked with the leopard complex since the 1970s.[14] The presence of CSNB in non-leopard breeds and horses suggested that the two conditions might be located on close, but separate genes. However, one study used ERG findings to diagnose all the homozygous Lp subjects with CSNB, while all heterozygotes and non-Lp horses were free from the disorder.[8] The gene to which Lp has now been localized encodes a protein that channels calcium ions, a key factor in the transmission of nerve impulses. This protein, which is found in the retina and the skin, existed in fractional percentages of the normal levels in homozygous Lp/Lp horses.[7] A 2008 study theorizes that both CSNB and leopard complex spotting patterns are linked to the TRPM1 gene.[15]

Equine Recurrent Uveitis (ERU) is also present in the breed. Appaloosas have an eightfold greater risk of developing Equine Recurrent Uveitis (ERU) than all other breeds combined. Up to 25% of all horses with ERU may be Appaloosas. Uveitis in horses has many causes, including eye trauma, disease, and bacterial, parasitic and viral infections, but ERU is characterized by recurring episodes of uveitis, rather than a single incident. If not treated, ERU can lead to blindness, which occurs more often in Appaloosas than in other breeds.[16] Up to 80% of all uveitis cases are found in Appaloosas, with physical characteristics including light colored coat patterns, little pigment around the eyelids and sparse hair in the mane and tail denoting more at-risk individuals.[17] Researchers may have identified a gene region containing an allele that makes the breed more susceptible to the disease.[18]

Prevalence

The Appaloosa horse is the breed best known for the leopard complex patterns, though the complex also characterizes the Knabstrupper, as well as breeds related to the Appaloosa such as the Pony of the Americas and Colorado Ranger.[2] The gene is also relatively common in the Falabella, the Noriker and the related South German Coldblood.[4][8] The existence of leopard-spotted coats among Asian breeds such as the Karabair and Mongolian Altai has been recorded since ancient times, and suggests that the gene is very old.[8] Leopard complex patterns may exist in low frequencies among some other breeds, depending on whether horses with leopard complex genetics existed in the foundation bloodstock for a given breed.

In cave art

The approximately 25,000-year-old paintings "Dappled Horses of Pech Merle" in a cave in France depict spotted horses with a leopard pattern. Archaeologists had debated over whether the artists were painting what they saw or whether the spotted horses had some symbolic meaning. However, a 2011 study of the DNA of ancient horses found that leopard complex was present, and therefore the cave painters most likely did see real spotted horses.[12]

References

- Terry, RB; Archer S; Brooks S; Bernoco D; Bailey E (2004). "Assignment of the appaloosa coat colour gene (LP) to equine chromosome 1". Animal Genetics. International Society for Animal Genetics. 35 (2): 134–137. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2004.01113.x. PMID 15025575.

- Sheila Archer (2008-08-31). "Studies Currently Underway". The Appaloosa Project. Archived from the original on 2008-08-24. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- "Appaloosa". Equine Color. December 2002. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- Sponenberg, D. Phillip (1982). "The inheritance of leopard spotting in the Noriker horse". The Journal of Heredity. The American Genetic Association. 5 (73): 357–359. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109669.

- Sponenberg, Dan Phillip (2003-04-11) [1996-01-15]. "5/Patterns Characterized by Patches of White". Equine Coat Color Genetics (2 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 93–4. ISBN 978-0-8138-0759-1.

- "Guide to Identifying an Appaloosa". Registration. Appaloosa Horse Club. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- Bellone, Rebecca R; Brooks SA; Sandmeyer L; Murphy BA; Forsyth G; Archer S; Bailey E; Grahn B (August 2008). "Differential Gene Expression of TRPM1, the Potential Cause of Congenital Stationary Night Blindness and Coat Spotting Patterns (LP) in the Appaloosa Horse (Equus caballus)". Genetics. Genetics Society of America. 179 (4): 1861–1870. doi:10.1534/genetics.108.088807. PMC 2516064. PMID 18660533.

- Sandmeyer, Lynne S.; Breaux CB; Archer S; Grahn BH (2007). "Clinical and electroretinographic characteristics of congenital stationary night blindness in the Appaloosa and the association with the leopard complex". Veterinary Ophthalmology. 6 (10): 368–375. doi:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2007.00572.x. PMID 17970998.

- Based on images from Sponenberg 2003, 153-156

- Identifying the Appaloosa Horse

- Sponenberg 2003, p. 90

- Pruvost, M.; Bellone, R.; Benecke, N.; Sandoval-Castellanos, E.; Cieslak, M.; Kuznetsova, T.; Morales-Muniz, A.; O'Connor, T.; Reissmann, M.; Hofreiter, M.; Ludwig, A. (7 November 2011). "Genotypes of predomestic horses match phenotypes painted in Paleolithic works of cave art". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (46): 18626–18630. doi:10.1073/pnas.1108982108. PMC 3219153. PMID 22065780. Lay summary – Ancient DNA provides new insights into cave paintings of horses.

- . doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078280 //doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0078280. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Witzel CA, Joyce JR, Smith EL. Electroretinography of congenital night blindness in an Appaloosa filly. Journal of Equine Medicine and Surgery 1977; 1: 226–229.

- Oke, Stacey, DVM, MSc (August 31, 2008). "Shedding Light on Night Blindness in Appaloosas". The Horse. Retrieved 2009-02-07.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sandmeyer, Lynne (July 28, 2008). "Equine Recurrent Uveitis (ERU)". The Appaloosa Project. Archived from the original on April 26, 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- Loving, Nancy (April 19, 2008). "Uveitis: Medical and Surgical Treatment". The Horse. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- "Abstracts: 36th Annual Meeting of the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists, Nashville, TN, US, October 12–15, 2005". Veterinary Ophthalmology. 8 (6): 437–450. November 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2005.00442.x. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

Based on these data, we conclude that a susceptibility allele for ERU in Appaloosas exists in the MHC region.