Lewis Hunton

Lewis Hunton (August 1814 – 17 February 1838) was a geologist who made important early contributions to the development of the idea that the geological succession could be sub-divided through analysis of its fossil content, at a time when such ideas were yet to be widely accepted. This principle, later dubbed biostratigraphy, became a fundamental aspect of the modern science of geology. Little detail of his life exists and, as far as the author can ascertain, there are no surviving images of Lewis.

Early Life & Influences

Born at Hummersea House near Loftus, and raised on the rugged Cleveland coast notable for its fine exposures of Lower and Middle Jurassic strata, Hunton was christened at St. Leonard's Church, Loftus on 6 August 1814. His father William (1789-1863) and grandfather, also William (1761-1809), acted as Alum Agent and Alum Maker respectively at Loftus Alum Works using shale from adjoining quarries on some of Britain's highest sea cliffs. The Hunton family's close associations with the Yorkshire alum trade, which flourished in north east Yorkshire (Cleveland) between ca.1604 and 1871, played an important role in influencing Lewis Hunton's later work in both geology and chemistry.[1]

Education and Work

Following early education, at a school for children of the local alum workers at Loftus, between 1833 and 1836 Hunton attended King's and University Colleges, London studying comparative anatomy, fossil zoology and natural philosophy. Lecturers at the time included the eminent Sir Charles Lyell (1797-1875). In 1836 Hunton also published his first scientific paper entitled: Remarks on a section of the Upper Lias and Marlstone of Yorkshire, showing the limited vertical range of the species of Ammonites, and other Testacea, with their value as geological tests[2] read at the Geological Society of London on 25 May of the same year.

.jpg.webp)

Fieldwork for this paper was carried out across north east Yorkshire including at many of the district's alum works. The vertical section eventually published was surveyed at Easington Heights, near Loftus and Boulby Alum Quarries, now a joint SSSI. From this fieldwork Hunton gained evidence for the notion that certain fossil species (particularly ammonites which are abundant in the district's Lower Jurassic rocks) could be found occupying very limited vertical horizons sometimes only a few centimetres thick. Hunton writes:

"Ammonites afford the most beautiful illustration of the subdivision of strata, for they appear to have been the least able, of all the Lias genera, to conform to a change of external consequences".

This variation in fossil species was used to sub-divide the vertical succession locally, and to correlate beds of the same relative age across wider areas. He further proposed formal rules for performing such surveys to ensure that the information recorded was accurate. In conclusion Hunton says:

"Ammonites from unequal geographical distribution may be more abundant in one place than another ... yet they constantly maintain an invariable relative position.".

"... one great source of error has hitherto been the collecting of specimens from the debris of the whole formation accumulated at the foot of the cliffs ... and the inferring of their position from the nature of the matrix."

Later in 1836 Hunton continued his work in Loftus Quarry excavating the remains of a 5-metre (16 feet) long ichthyosaur, or fish lizard, named Temnodontosaurus platyodon (formerly Ichthyosaurus platyodon). In 1869 this leviathan was donated by the Hunton family to Pannett Park Museum, Whitby where it remains on display (Specimen no. 5) along with many other fossils from the local area.

Hunton only produced one other published scientific work appearing in the London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine in 1837. The paper, on his other interest, chemistry, discusses combining sugar with alkalis and metallic oxides - reactions that would have been of interest to alum makers.[3][4]

Early Demise

In later life Hunton chose to alter the spelling of his forename to the French ’Louis’, it is thought because of his love of France in general and admiration of scientist Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier (1743-1794) in particular.

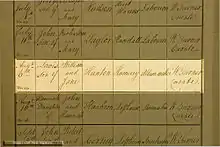

Aged only 23, and suffering ill health, the promising young scientist departed for the continent only to pass away, near Nîmes, of tuberculosis on 17 February 1838 whilst staying with pharmacist Alix Pleindoux.[5] A memorial stone in Loftus churchyard where many of the Hunton family are laid to rest reads:

"Sacred to the memory of Lewis son of William and Jane Hunton who died at A------ in the south of France, 17 Feb 1838"

It appears likely that Lewis does not lie alongside the rest of his family at Loftus but was buried in France. He is posthumously remembered by an ammonite (Tragophylloceras huntoni) named after him by Martin Simpson, curator at Whitby Museum, in 1843.

A special Service of Thanksgiving at St Leonard's Parish Church, Loftus-in-Cleveland on Sunday 14 September 2014 celebrated the 200th Anniversary of the birth of Lewis Hunton 1814 – 1838.[6]

References

- Torrens H. S. & Getty T. A.,1984; Louis Hunton, 1814–1838: English pioneer in ammonite biostratigraphy, Earth Sciences History, 3, 58–68

- Cadell, 1840; Transactions of the Geological Society of London, vol. 5 part 3

- Torrens, H.S. Hunton, Louis [Lewis] (bap. 1814, d. 1838), geologist and chemist

- Brewster, D. Taylor, R. & Phillips, R; 1837; The London & Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine Vol 11 pp152-156

- Appleton. P.G. 2011; The Loftus Alum Makers Private publication