Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In September 1640,[1] King Charles I issued writs summoning a parliament to convene on 3 November 1640.[lower-alpha 1] He intended it to pass financial bills, a step made necessary by the costs of the Bishops' Wars in Scotland. The Long Parliament received its name from the fact that, by Act of Parliament, it stipulated it could be dissolved only with agreement of the members;[2] and, those members did not agree to its dissolution until 16 March 1660, after the English Civil War and near the close of the Interregnum.[3]

The parliament sat from 1640 until 1648, when it was purged by the New Model Army. After this point, the remaining members of the House of Commons became known as the Rump Parliament. In the chaos following the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1658, General George Monck allowed the members barred in 1648 to retake their seats, so that they could pass the necessary legislation to allow the Restoration and dissolve the Long Parliament. This cleared the way for a new parliament to be elected, which was known as the Convention Parliament. Some key members of the Long Parliament, such as Sir Henry Vane the Younger and General Edmond Ludlow were barred from the final acts of the Long Parliament. They claimed the parliament was not legally dissolved, its final votes a procedural irregularity (words used contemporaneously "device" and "conspiracy") by General George Monck to ensure the restoration of King Charles II of England. On the restoration the general was awarded with a dukedom.

The Long Parliament later became a key moment in Whig histories of the seventeenth century. American Whig historian Charles Wentworth Upham believed the Long Parliament comprised "a set of the greatest geniuses for government that the world ever saw embarked together in one common cause" and whose actions produced an effect, which, at the time, made their country the wonder and admiration of the world, and is still felt and exhibited far beyond the borders of that country, in the progress of reform, and the advancement of popular liberty.[4] He believed its republican principles made it a precursor to the American Revolutionary War.

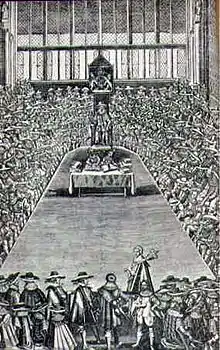

Execution of Strafford

Charles found himself unable to fund the Bishops Wars without taxes; in April 1640, Parliament was recalled for the first time in eleven years, but when it refused to vote taxes without concessions, he dissolved it after only three weeks. The humiliating terms imposed by the Scots Covenanters after a second defeat forced him to hold fresh elections in November, which produced a large majority for the opposition, led by John Pym.[5]

Parliament was almost immediately presented with a series of "Root and Branch petitions". These demanded the expulsion of bishops from the Church of England, reflecting widespread concern at the growth of "Catholic practices" within the church.[6] Charles' willingness to make war on the Protestant Scots, but not assist his exiled nephew Charles Louis, led to fears he was about to sign an alliance with Spain, a view shared by the experienced Venetian and French ambassadors.[lower-alpha 2][7]

This meant ending arbitrary rule was important not just for England, but the Protestant cause in general. Since direct attacks on the monarch were considered unacceptable, the usual route was to prosecute his 'evil counsellors.' Doing so showed even if the king was above the law, his subordinates were not, and he could not protect them; the intention was to make others think twice about their actions.[8]

Their main target was the Earl of Strafford, former Lord Deputy of Ireland; aware of this, he urged Charles to use military force to seize the Tower of London, and arrest any MP or peer guilty of 'treasonable correspondence with the Scots.'[lower-alpha 3] While Charles hesitated, Pym struck first; on 11 November Strafford was impeached, arrested, and sent to the Tower.[10] Other targets, including John Finch, fled abroad; Laud was impeached in December 1640, and joined Strafford in the Tower.[11]

At his trial in March 1641, Strafford was indicted on 28 counts of 'arbitrary and tyrannical government'. Even if these charges were proved, it was not clear they constituted a crime against the king, the legal definition of treason. If he went free, his opponents would replace him in the Tower, and so Pym immediately moved a Bill of Attainder, asserting Strafford's guilt and ordering his execution.[12]

Although Charles announced he would not sign the attainder, on 21 April, 204 MPs voted in favour, 59 against, while 250 abstained.[13] On 1 May, rumours of a military plot to release Strafford from the Tower led to widespread demonstrations in London, and on 7th, the Lords voted for execution by 51 to 9.[14] Claiming to fear for his family's safety, Charles signed the death warrant on 10 May, and Strafford was beheaded two days later.[15]

The Grand Remonstrance

This seemed to provide a basis for a programme of constitutional reforms, and Parliament voted Charles an immediate grant of £400,000. The Triennial Acts required Parliament meet at least every three years, and if the King failed to issue proper summons, the members could assemble on their own. Levying taxes without consent of Parliament was declared unlawful, including Ship money and forced loans, while the Star Chamber and High Commission courts abolished.[16]

These reforms were supported by many who later became Royalists, including Edward Hyde, Viscount Falkland, and Sir John Strangways.[17] Where they differed from Pym and his supporters was their refusal to accept Charles would not keep his commitments, despite evidence to the contrary. He reneged on those made in the 1628 Petition of Right, and agreed terms with the Scots in 1639, while preparing another attack. Both he and Henrietta Maria openly told foreign ambassadors any concessions were temporary, and would be retrieved by force if needed.[18]

In this period, 'true religion' and 'good government' were seen as one and the same. Although the vast majority believed a 'well-ordered' monarchy was a divinely mandated requirement, they disagreed on what 'well-ordered' meant, and who held ultimate authority in clerical affairs. Royalists generally supported a Church of England governed by bishops, appointed by, and answerable to, the king; most Parliamentarians were Puritans, who believed he was answerable to the leaders of the church, appointed by their congregations.[19]

However, Puritan meant anyone who wanted to reform, or 'purify', the Church of England, and contained many different opinions. Some simply objected to Laud's reforms; Presbyterians like Pym wanted to reform the Church of England, along the same lines as the Church of Scotland. Independents believed any state church was wrong, while many were also political radicals like the Levellers. Presbyterians in England and Scotland gradually came to see them as more dangerous than the Royalists; an alliance between these three groups eventually led to the Second English Civil War in 1648.[20]

While it is not clear there was a majority for removing bishops from the Church, their presence in the House of Lords became increasingly resented due to their role in blocking many of these reforms.[21] Tensions came to a head in October 1641 with the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion; both Charles and Parliament supported raising troops to suppress it, but neither trusted the other with their control.[22]

On 22 November, the Commons passed the Grand Remonstrance by 159 votes to 148, and presented it to Charles on 1 December. The first half listed over 150 perceived 'misdeeds', the second proposed solutions, including church reform and Parliamentary control over the appointment of royal ministers. In the Militia Ordinance, Parliament asserted control over appointment of army and navy commanders; Charles rejected the Grand Remonstrance and refused to assent to the Militia Ordinance. It was at this point moderates like Hyde decided Pym and his supporters had gone too far, and switched sides.[10]

First English Civil War

Increasing unrest in London culminated in 23 to 29 December 1641 with widespread riots in Westminster, while the hostility of the crowd meant the bishops stopped attending the Lords.[23] On 30 December, Charles induced John Williams, Archbishop of York and eleven other bishops, to sign a complaint, disputing the legality of any laws passed by the Lords during their exclusion. This was viewed by the Commons as inviting the king to dissolve Parliament; all twelve were arrested.[24]

On 3 January 1642, Charles ordered his Attorney-general to bring charges of treason against Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester, and Five Members of the Commons; Pym, John Hampden, Denzil Holles, Arthur Haselrig, and William Strode. This confirmed fears he intended to use force to shut down Parliament, while the members were prewarned, and evaded arrest.[25]

Soon after, Charles left London, accompanied by many Royalist MPs, and members of the Lords, a major tactical mistake. By doing so, he abandoned the largest arsenal in England and the commercial power of the City of London and guaranteed his opponents majorities in both houses. In February, Parliament passed the Clergy Act, excluding bishops from the Lords; Charles approved it, since he had already decided to retrieve all such concessions by assembling an army.[26]

In March 1642, Parliament decreed its own Parliamentary Ordinances were valid laws, even without royal assent. The Militia Ordinance gave them control of the local militia, or Trained Bands; those in London were the most strategically critical, because they could protect Parliament from armed intervention by any soldiers which Charles had near the capital. Charles declared Parliament in rebellion and began raising an army, by issuing a competing Commission of Array.

At the end of 1642, he set up his court at Oxford, where the Royalist MPs formed the Oxford Parliament. In 1645 Parliament reaffirmed its determination to fight the war to a finish. It passed the Self-denying Ordinance, by which all members of either House of Parliament resigned any military commands, and formed the New Model Army under the command of Fairfax and Cromwell.[27] The New Model Army soon destroyed Charles' armies, and by early 1646, he was on the verge of defeat.[28]

Charles left Oxford in disguise on 27 April; on 6 May, Parliament received a letter from David Leslie, commander of Scottish forces besieging Newark, announcing that he had the king in custody. Charles ordered the Royalist governor, Lord Belasyse, to surrender Newark, and the Scots withdrew to Newcastle, taking the king with them.[29] This marked the end of the First English Civil War.

Second English Civil War

Many Parliamentarians had assumed military defeat would force Charles to compromise, which proved a fundamental misunderstanding of his character. When Prince Rupert suggested in August 1645 the war was lost, Charles responded he was correct from a military viewpoint, but 'God will not suffer rebels and traitors to prosper'. This deeply-held conviction meant he refused any substantial concessions.[30] Aware of divisions among his opponents, he used his position as king of both Scotland and England to deepen them, assuming that he was essential to any government; while this was true in 1646, by 1648 key actors believed it was pointless to negotiate with someone who could not be trusted to keep any agreement.[31]

Unlike in England, where Presbyterians were a minority, the 1639 and 1640 Bishops Wars resulted in a Covenanter, or Presbyterian government, and Presbyterian kirk, or Church of Scotland. The Scots wanted to preserve these achievements; the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant was driven by their concern at the implications for this settlement if Charles defeated Parliament. By 1646, they viewed Charles as a lesser threat than the Independents, who opposed their demand for a unified, Presbyterian church of England and Scotland; Cromwell claimed he would fight rather than agree to it.[32]

In July, the Scots and English commissioners presented Charles with the Newcastle Propositions, which he rejected. His refusal to negotiate created a dilemma for the Covenanters. Even if Charles agreed to a Presbyterian union, there was no guarantee it would be approved by Parliament. Keeping him was too dangerous; as subsequent events proved, whether Royalist or Covenanter, many Scots supported his retention. In February 1647, they agreed to a financial settlement, handed Charles over to Parliament, and retreated into Scotland.[33]

In England, Parliament was struggling with the economic cost of the war, a poor 1646 harvest, and a recurrence of the plague. The Presbyterian faction had the support of the London Trained Bands, the Army of the Western Association, leaders like Rowland Laugharne in Wales, and parts of the Royal Navy. By March 1647, the New Model was owed more than £3 million in unpaid wages; Parliament ordered it to Ireland, stating that only those who agreed would be paid. When their representatives demanded full payment for all in advance, it was disbanded.[34]

The New Model refused to be disbanded; in early June, Charles was removed from his Parliamentary guards, and taken to Thriplow, where he was presented with the Army Council's terms. Though they were more lenient than the Newcastle Propositions, Charles rejected them; on 26 July, pro-Presbyterian rioters burst into Parliament, demanding he be invited to London. In early August, Fairfax and the New Model took control of the city; this re-established command authority over the rank and file, completed at Corkbush in November.[35]

In late November, the king escaped from his guards, and made his way to Carisbrooke Castle. In April 1648, the Engagers became a majority in the Scottish Parliament; in return for restoring him to the English throne, Charles agreed to impose Presbyterianism in England for three years, and suppress the Independents. His refusal to take the Covenant himself split the Scots; the Kirk Party did not trust Charles, objected to an alliance with English and Scots Royalists, and denounced the Engagement as 'sinful.'[36]

After two years of constant negotiation, and refusal to compromise, Charles finally had the pieces in place for a rising by Royalists, supported by some English Presbyterians, and Scots Covenanters. However, lack of co-ordination meant the Second English Civil War was quickly suppressed.

Rump Parliament (6 December 1648 – 20 April 1653)

Divisions emerged between various factions, culminating in Pride's Purge on 7 December 1648, when, under the orders of Oliver Cromwell's son-in-law Henry Ireton, Colonel Pride physically barred and arrested 41 of the members of Parliament. Many of the excluded members were Presbyterians. Henry Vane the Younger removed himself from Parliament in protest of this unlawful action by Ireton. He was not party to the execution of Charles I, although Cromwell was. In the wake of the ejections, the remnant, the Rump Parliament, arranged for the trial and execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649. It was also responsible for the setting up of the Commonwealth of England in 1649.

Henry Vane the Younger was persuaded to rejoin Parliament on 17 February 1649 and a Council of state was installed, into whose hands the executive government of the nation was committed. Sir Henry Vane was appointed a member of the Council. Cromwell used great pains to induce Vane to accept the appointment, and after many consultations, he so far prevailed in satisfying Vane of the purity of his principles in reference to the Commonwealth, as to overcome his reluctance again to enter the public service. Sir Henry Vane was for some time President of the Council, and, as Treasurer and Commissioner for the Navy, he had almost the exclusive direction of that branch of public service.[37]

Cromwell "well knew that while the Long Parliament, that noble company, who had fought the great battle of liberty from the beginning, remained in session, and such men as Vane were enabled to mingle in its deliberations, it would be utterly useless for him to think of executing his purposes" (to set up a Protectorate or Dictatorship). Henry Vane was working on a Reform Bill. Cromwell knew "that if the Reform Bill should be suffered to pass, and a House of Commons be convened, freely elected on popular principles, and constituting a full and fair and equal representation, it would be impossible ever after to overthrow the liberties of the people, or break down the government of the country". According to General Edmund Ludlow (an unapologetic supporter of the Good Old Cause who lived in exile after the Restoration), this reform bill provided for an equal representation of the people, disfranchised several boroughs which had ceased to have a population in proportion to representation, fixed the number of the House at four hundred".[38] It would have "secured to England and to the rest of the world the blessings of republican institutions, two centuries earlier than can now be expected".[38]

"Harrison, who was in Cromwell's confidence on this occasion, rose to debate the motion, merely in order to gain time. Word was carried to Cromwell, that the House were on the point of putting the final motion; and Colonel Ingoldby hastened to Whitehall to tell him, that, if he intended to do anything decisive, he had no time to lose". Once the troops were in place Cromwell entered the assembly. He was dressed in a suit of plain black; with grey worsted stockings. He took his seat; and appeared to be listening to the debate. As the Speaker was about to rise to put the question, Cromwell whispered to Harrison, "Now is the time; I must do it". As he rose, his countenance became flushed and blacked by the terrific passions which the crisis awakened. With the most reckless violence of manner and language, he abused the character of the House; and, after the first burst of his denunciations had passed, suddenly changing his tone, he exclaimed, "You think, perhaps, this is not parliamentary language; I know it; nor are you to expect such from me". He then advanced out into the middle of the hall, and walked to and fro, like a man beside himself. In a few moments he stamped upon the floor, the doors flew open and a file of musketeers entered. As they advanced, Cromwell exclaimed, looking over the House, "You are no Parliament; I say you are no Parliament; begone, and give place to honester men".[39]

"While this extraordinary scene was transacting, the members, hardly believing their own ears and eyes, sat in mute amazement, horror, and pity of the maniac traitor who was storming and raving before them. At length Vane rose to remonstrate, and call him to his senses; but Cromwell, instead of listening to him, drowned his voice, repeating with great vehemence, and as though with the desperate excitement of the moment, "Sir Harry Vane! Sir Harry Vane! Good Lord deliver me from Sir Harry Vane!" He then seized the records, snatched the bill from the hands of the clerk, drove the members out at the point of the bayonet, locked the doors, put the key in his pocket, and returned to Whitehall.[40]

Oliver Cromwell forcibly disbanded the Rump in 1653 when it seemed to be planning to perpetuate itself rather than call new elections as had been agreed. It was followed by Barebone's Parliament and then the First, Second and Third Protectorate Parliament.

Recall of the Rump (7 May 1659 – 20 February 1660)

After Richard Cromwell, who had succeeded his father Oliver as Lord Protector in 1658, was effectively deposed by an officers' coup in April 1659, the officers re-summoned the Rump Parliament to sit. It convened on 7 May 1659, but after five months in power it again clashed with the army (led by John Lambert) and was again forcibly dissolved on 13 October 1659. Once again, Sir Henry Vane was the leading catalyst for the republican cause in opposition to force by the military.[41]

The persons connected with the administration as it existed at the death of Oliver were, of course, interested in keeping things as they were. Also, it was necessary for someone to assume the reins of government until the public will could be ascertained and brought into exercise. Henry Vane was elected to Parliament at Kingston upon Hull, but the certificate was given to another. Vane proceeded to Bristol, entered the canvass, and received the majority. Again the certificate was given to another. Finally Vane proceeded to Whitechurch in Hampshire and was elected a third time and was this time seated in Parliament. Vane managed the debates on behalf of the House of Commons. One of Vane's speeches effectively ended Richard Cromwell's career:[41]

Mr. Speaker, among all the people of the universe, I know none who have shown so much zeal for the liberty of their country, as the English, at this time, have done. They have, by the help of Divine Providence, overcome all obstacles, and have made themselves free ... I know not by what misfortune, we are fallen into the error of those, who poised the Emperor Titus to make room for Domitian, who made away Augustus that they might have Tiberius, and changed Claudius for Nero ... whereas the people of England are now renowned, all over the world, for their great virtue and discipline; and yet suffer an idiot, without courage, without sense, nay, without ambition, to have dominion in a country of liberty. One could bear a little with Oliver Cromwell, though, contrary to his oath of fidelity to Parliament, contrary to his duty to the public, ... But as for Richard Cromwell, his son, who is he? Where are his titles ... For my part, I declare, Sir, it shall never be said that I made such a man my master.[41]

This speech swept everything before it. The Rump Parliament which Oliver Cromwell had dispersed in 1653 was once more summoned to assemble, by a declaration from the Council of Officers dated on 6 May 1659.[41]

Edmond Ludlow made several attempts to reconcile the army and parliament in this time period but was ultimately unsuccessful. Parliament ordered the regiments of Colonel Morley and Colonel Moss to march to Westminster for their security, and sent for the rest of the troops that were about London to draw down to them also with all speed.[42]

In October 1659, Colonel Lambert and various subordinate members of the army, acting in the military interest, resisted Colonel Morley and others who were defending the rump Parliament. Colonel Lambert, Major Grimes, and Colonel Sydenham eventually gained their points, and placed guards both by land and water, to hinder the members of Parliament from approaching the House. Colonel Lambert subsequently acquitted himself to Henry Vane the Younger, Edmond Ludlow and the "Committee on Safety," an instrument of the Wallingford House party acting under their misdirection.[43]

Nevertheless, Parliament was closed once again by military force until such time that the army and leaders of Parliament could effect a resolution. Rule then passed to an unelected Committee of Safety, including Lambert and Vane; pending a resolution or compromise with the Army.

During these disorders, the Council of State still assembled at the usual place, and:

the Lord President Bradshaw, who was present, though by long sickness very weak and much extenuated, yet animated by his ardent zeal and constant affection to the common cause, upon hearing Col Syndenham's justifications of the proceedings of the army in again disrupting parliament, stood up and interrupted him, declaring his abhorrence of that detestable action, and telling the council, that being now going to his God, he had not patience to sit there to hear his great name so openly blasphemed; and thereupon departed to his lodgings, and withdrew himself from public employment.[44]

The Council of Officers at first attempted to come to some agreement with the leaders of Parliament.[45] On 15 October 1659, the Council of Officers appointed ten persons to "consider of fit ways and means to carry on the affairs and government of the Commonwealth". On 26 October 1659 the Council of Officers appointed a new Committee of Safety of twenty-three members.[46]

On 1 November 1659, the Committee of Safety nominated a committee "to consider of and prepare a form of government to be settled over the three nations in the way of a free state and Commonwealth, and afterwards to present it to the Committee of Safety for their further considerations".[47]

The designs of General Fleetwood of the army and the Wallingford House party were now suspected as being in a possible alliance with Charles II.[48] According to Edmond Ludlow:

The Wallingford House party, as if infatuated by a superior power to procure their own destruction, continued obstinately to oppose the Parliament, and fixed in their resolution to call another (that is a reformed Parliament more agreeable to their interests). On the other side, I was sorry to find most of the Parliament men as stiff, in requiring an absolute submission to their authority as if no differences had happened among us, nor the privileges of Parliament ever been violated, peremptorily insisting upon the entire subjection of the army, and refusing to hearken to any terms of accommodation, though the necessity of affairs seemed to demand it, if we would preserve our cause from ruin.[49]

Edmond Ludlow warned both the Army and key members of Parliament that unless a compromise could be made it would "render all the blood and treasure that had been spent in asserting our liberties of no use to us, but also force us under such a yoke of servitude, that neither we nor our posterity should be able to bear".[50]

Starting on 17 December 1659, Henry Vane representing the Parliament, Major Saloway and Colonel Salmon with powers from the officers of the army to treat with the fleet, and Vice-Admiral Lawson met in negotiating a compromise. The navy was very adverse to any proposal of terms to be made with the Parliament before Parliament's readmission, insisting upon the absolute submission of the army to the authority of Parliament.[51] A plan was then put in place declaring a resolution to join with the Generals at Portsmouth, Colonel Monck, and Vice-Admiral Lawson, but it was still unknown to the republican party that Colonel Monck was in league with King Charles II.[52]

Colonel Monck, though a hero to the restoration of King Charles II, was also treacherously disloyal to the Long Parliament, to his oath to the present Parliament, and to the Good Old Cause. Ludlow stated in early January 1660 when in conversation with several key officers of the army:

"Then", said Capt. Lucas, "you do not think us to be for the Parliament?" "No indeed", said I; "and it is most manifest to me, that the design of those who now govern the Council of Officers, though at present it be covered with pretences for the Parliament, is to destroy both them and their friends, and to bring in the son of the late King".[53]

This statement may be verified by the many executions of key Parliament members and Generals after the restoration of King Charles II. Therefore, the restoration of King Charles II could not be an act of the Long Parliament acting freely under its own authority, but only under the influence of the sword by Colonel Monck, who traded his loyalties for the present Long Parliament, in preference to a reformed Long Parliament and to the restoration of King Charles II.

General George Monck, who had been Cromwell's viceroy in Scotland, feared that the military stood to lose power and secretly shifted his loyalty to the Crown. As he began to march south, Lambert, who had ridden out to face him, lost support in London. However, the Navy declared for Parliament, and on 26 December 1659 the Rump was restored to power.

On 9 January 1660, Monck arrived in London and his plans were communicated. Whereupon Henry Vane the Younger was discharged from being a member of the Long Parliament; and Major Saloway was reproved for his role and committed to the Tower during the pleasure of the house. Lieutenant-General Fleetwood, Col. Sydenham, Lord Commissioner Whitlock, Cornelius Holland, and Mr. Strickland were required to clear themselves touching their deportment in that affair. High treason was also declared against Miles Corbet, Cor. John Jones, Col. Thomlinson, and Edmond Ludlow on 19 January 1660. 1,500 other officers were removed from their command and "scarce one of ten of the old officers of the army were continued". Any known Anabaptists in the army were specifically discharged. So tame had Parliament become, that though it was most visible that Monk's letters and Arthur Haslerig's instructions were designed for the dissolution of the Long Parliament, they were obeyed by the remainder of the members and all these designs were to be put into execution. Though named by Parliament for treason, Miles Corbet and Edmond Ludlow were for a while were permitted to continue to sit with Parliament, and for a time the charges against these men were dropped.[54][55]

Restoration and dissolution of the Long Parliament (21 February – 16 March 1660)

After his initial show of deference to the Rump, Monck quickly found them unwilling to continue in cooperation with his plan for an election of a new parliament (the Rump Parliament believed Monck was accountable to them and had its own plan for free elections); so on 21 February 1660 he forcibly reinstated the members 'secluded' by Pride's purge in 1648, so that they could prepare legislation for the Convention Parliament. Some of the Rump Parliament were opposed and refused to sit with the Secluded Members.

On 27 February 1660, "the new Council of State being informed of some designs against the usurped power, issued out warrants for apprehending divers officers of the army; and having some jealousy of others that were members of Parliament, they procured an order of their House to authorize them to seize any member who had not sat since the coming in of the Secluded Members, if there should be occasion.[56]

When the house was ready to pass the act for dissolution, Crew who had been as forward as any man in beginning and carrying on the war against the last King, moved, that before they dissolved themselves, they would bear their witness against the horrid murder, as he called it, of the King.[57] According to Ludlow:

Mr. Thomas Scott, who had been so much deluded by the hypocrisy of Monk ... said: 'That though he knew not where to hide his head at that time, yet he durst not refuse to own, that not only his hand, but his heart also was in it' and after he had produced divers reasons to prove the justice of it, he concluded, 'that he should desire no greater honor in this world, than that the following inscription might be engraved on his tomb; "Here lies one who had a hand and a heart in the execution of Charles Stuart late King of England.' Having said this, he and most of the members who had a right to sit in Parliament, withdrew from the House; so that there was not the fourth part of a quorum of lawful members present in the House when the Secluded Members, who had been voted out of the Parliament by those that had an undisputed authority over their own members, undertook to dissolve the Parliament, which was not to be done, unless by their own consent; and whether that consent was ever given, is submitted to the judgement of all impartial men.[58]

Having called for elections for a new Parliament to meet on 25 April, the Long Parliament was dissolved on 16 March 1660.

Finally, on 22 April 1660, "Major-General Lambert's party was dispersed" and General Lambert taken prisoner by Colonel Ingoldsby.[59]

Aftereffects: royalist and republican theories

"Hitherto Monk had continued to make solemn protestations of his affection and fidelity to the Commonwealth interest, against a King and House of Lords; but the new militia being settled, and a Convention, calling themselves a Parliament and fit for his purpose, being met at Westminster, he sent to such lords as had sat with the Parliament till 1648, to return to the place where they used to sit, which they did, upon assurance from him, that no others should be permitted to sit with them; which promise he also broke, and let in not only such as had deserted to Oxford, but the late created lords. And Charles Stuart, eldest son of the late King, being informed of these transactions, left the Spanish territories where he then resided, and by the advice of Monk went to Breda, a town belonging to the States of Holland: from when he sent his letters and a declaration to the two House by Sir John Greenvil; whereupon the nominal House of Commons, though called by a Commonwealth writ in the name of the Keepers of the Liberties of England, passed a vote [on about April 25, 1660], 'That the government of the nation should be by a King, Lords and Commons, and that Charles Stuart should be proclaimed King of England'".[60]

"The Lord Mayor, Sheriffs and Aldermen of the City, treated their King with a collation under a tent, placed in St. George's Fields; and five or six hundred citizens cloathed in coats of black velvet, and (not improperly) wearing chains about their necks, by an order of the Common Council, attended on the triumph of that day; ... and those who had been so often defeated in the field, and had contributed nothing either of bravery or policy to this change, in ordering the souldiery to ride with swords drawn through the city of London to White Hall, the Duke of York and Monk leading the way; and intimating (as was supposed) a resolution to maintain that by force which had been obtained by fraud".[61]

Initially seven, and later 'twenty persons were put to death for life and estate.' These included: Chief Justice Coke, who had been Solicitor to the High Court of Justice, Major-General Harrison, Col. John Jones (also a member of the High Court of Justice), Mr. Thomas Scot, Sir. Henry Vane, Sir. Arthur Haslerig, Sir. Henry Mildmay, Mr. Robert Wallop, the Lord Mounson, Sir. James Harrington, Mr. James Challoner, Mr. John Phelps, Mr. John Carew, Mr. Hugh Peters, Mr. Gregory Clement, Colonel Adrian Scroop, Col. Francis Hacker, Col. Daniel Axtel. Among those who appeared the most basely subservient to these 'exorbitancies' of the Court, 'Mr. William Prynn was singularly remarkable' and attempted to add to these all who 'abjured the family of the Stuarts' previously, though this motion failed.[62][63]

"John Finch who had been accused of high treason twenty years before, by a full Parliament, and who by flying from their justice had saved his life, was appointed to judge some of those who should have been his judges; and Sir. Orlando Bridgman, who upon his submission to Cromwell had been permitted to practice the law in a private manner, and under that colour had served both as spy and agent for his master, was entrusted with the principal management of this tragic scene; and in his charge to the Grand Jury, had the assurance to tell them 'That no authority, no single person, or community of men; not the people collectively or representatively, had any coercive power over the King of England'".[64]

In framing the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion, the House of Commons were unwilling to except Sir Henry Vane, Sir. Arthur Haslerig, and Major-General Lambert as they had no immediate hand in the death of the King, and there was as much reason to except them as most of the members of Parliament from its benefits. In Henry Vane's case the House of Lords were desirous of having him specifically excepted, so as to leave him at the mercy of the government and thus restrain him from the exercise of his great talents in promoting his favourite republican principles at any time during the remainder of his life. At a conference between the two Houses, it was concluded that the Commons should consent to except him from the act of indemnity, the Lords agreeing, on their part, to concur with the other House in petitioning the King, in case of the condemnation of Vane, not to carry the sentence into execution. General Edmond Ludlow, still loyal to the Rump Parliament was also excepted.[41][65]

According to contemporary royalist legal theory, the Long Parliament was regarded as having been automatically dissolved from the moment of Charles I's execution on 30 January 1649. This view was confirmed by a court ruling during the treason trial of Henry Vane the Younger – a ruling that Henry Vane himself had concurred with in opposition to Oliver Cromwell years earlier.

The trial given to Vane as to his own person, and defence of his own part played for the Long Parliament was a foregone conclusion. It was not a fair trial as both his defence, and deportment at the time of defence bears out. He was not given legal counsel (other than the judges that sat at his trial); and was left to conduct his own defence after years in prison. Sir Henry Vane maintained the following at his trial:

- Whether the collective body of the Parliament can be impeached of high treason?

- Whether any person, acting by authority of Parliament, can (so long as he acting by that authority) commit treason?

- Whether matters, acted by that authority, can be called in question in an inferior court?

- Whether a king de jure, and out of possession, can have treason committed against him?

King Charles II did not keep the promise made to the house but executed the sentence of death on Sir Henry Vane the Younger. The solicitor, openly declared in his speech afterwards "that he (Henry Vane) must be made a public sacrifice". One of his judges stated: "We knew not how to answer him, but we know what to do with him".

Edmond Ludlow one of the members of Parliament excepted by the act of indemnity, fled to Switzerland after the restoration of King Charles II, where he wrote his memoirs of these events.

The Long Parliament began with the execution of Lord Stafford, and effectively ended with the execution of Henry Vane the Younger.

The republican theory is that the goal and aim of the Long Parliament was to institute a constitutional, balanced, and equally representative form of government along similar lines as were later accomplished in America by the American Revolution. It is clear from the writings of both Ludlow, Vane, and historians of the early American period such as Upham, that this is what they were striving for and why they were excepted from the acts of indemnity. The republican theory also suggests that the Long Parliament would have been successful in these necessary reforms except through the forceful intervention of Oliver Cromwell (and others) in removing the loyalists party, the unlawful execution of King Charles I, later dissolving the Rump Parliament; and finally the forceful dissolution of the reconvened Rump Parliament by Monck when less than a fourth of the required members were present. It is believed that in many ways this struggle was but a precursor to the American Revolution.[66]

Notable members of the Long Parliament

- Carew Raleigh

- Sir John Coolepeper

- Oliver Cromwell

- Sir Simonds D'Ewes

- George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol

- Lucius Cary, 2nd Viscount Falkland

- John Hampden

- Sir Robert Harley

- Major-General Harrison

- Sir Arthur Haselrig

- Denzil Holles, 1st Baron Holles

- Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon

- William Lenthall

- Edmond Ludlow

- John Pym

- Sir Benjamin Rudyerd

- William Russell, 1st Duke of Bedford

- Oliver St John

- Sir Francis Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Trowbridge

- Sir Nicholas Slanning

- William Strode

- James Temple

- Sir Henry Vane the Elder

- Sir Henry Vane the Younger

- Sir Nicholas Crisp

- Samuel Vassall

- Sir Thomas Myddelton

Timeline

- Triennial Act, passed 15 February 1641

- Archbishop William Laud imprisoned 26 February 1641

- Act against Dissolving the Long Parliament without its own Consent 11 May 1641

- Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford executed 12 May 1641

- Abolition of the Star Chamber 5 July 1641

- Ship Money declared illegal 7 August 1641

- Grand Remonstrance 22 November 1641

- Militia Bill December 1641

- The King's answer to the petition accompanying the Grand Remonstrance 23 December 1641

- The King's attempt to seize the Five Members 4 January 1642

- The King and Royal Family leave Whitehall for Hampton Court. January 1642

- The King leaves Hampton Court for the North 2 March 1642

- Militia Ordinance agreed by Lords and Commons 5 March 1642

- Parliament decreed that Parliamentary Ordinances were valid without royal assent following the King's refusal to assent to the Militia Ordinance 15 March 1642

- Adventurers Act to raise money to suppress the Irish Rebellion of 1641 19 March 1642

- The Solemn League and Covenant 25 September 1643

- Ordinance appointing the First Committee of both Kingdoms 16 February 1644

- The Self-denying Ordinance 4 April 1645

- Parliament accepts the King's terms 1 December 1648

- Pride's Purge (Start of the Rump Parliament) 7 December 1648

- Execution of Charles I 30 January 1649

- Excluded members of the Long Parliament reinstated by George Monck 21 February 1660

- Having called for elections for a Parliament to meet on 25 April, the Long Parliament dissolved itself on 16 March 1660

See also

- List of MPs elected to the English parliament in 1640 (November)

- List of MPs in the English parliament in 1645 and after

- List of Parliaments of England

Notes

- This article uses the Julian calendar with the start of year adjusted to 1 January – for a more detailed explanation, see Old Style and New Style dates#Differences between the start of the year old style and new style dates: differences between the start of the year.

- A perspective summarised by Francis Rous in 1641; "For Arminianism is the span of a Papist, and if you mark it well, you shall see an Arminian reaching to a Papist, a Papist to a Jesuit, a Jesuit to the Pope, and the other to the King of Spain. And having kindled fire in our neighbours, they now seek to set on flame this kingdom also."

- Scottish victory at Newburn in August was marked with widespread celebrations in London, and there was frequent contact between the Parliamentary opposition and the Covenanters.[9]

References

- Cobbett, William (1812). Cobbett's Parliamentary History of England. 2. p. 592.

- Upham 1842, p. 180.

- House of Commons 1802, p. 880.

- Upham 1842, p. 173.

- Jessup 2013, p. 25.

- Rees 2016, p. 2.

- Wedgwood 1955, p. 248.

- Wedgwood 1955, pp. 250-256.

- Harris 2014, pp. 345-346.

- Harris 2014, pp. 457-458.

- Gregg 1981, p. 325.

- Carlton 1995, p. 224.

- Smith 1999, p. 123.

- Harris 2014, p. 410.

- Coward 1994, p. 191.

- Gregg 1981, p. 335.

- Harris 2014, p. 411.

- Wedgwood 1958, pp. 26–27.

- Macloed 2009, pp. 5–19 passim.

- Rees 2016, pp. 103-105.

- Rees 2016, pp. 7–8.

- Hutton 2003, p. 4.

- Smith 1979, pp. 315–317.

- Rees 2016, pp. 9–10.

- Harris 2014, pp. 452-455.

- Manganiello 2004, pp. 60-61.

- Wedgwood 1970, p. 373.

- Wedgwood 1970, p. 428.

- Royle 2004, p. 393.

- Royle 2004, pp. 354-355.

- Wedgwood 1958, pp. 546-548.

- Rees 2016, pp. 118-119.

- Wedgwood 1958, pp. 603-605.

- Rees 2016, pp. 173-174.

- Grayling 2017, p. 23.

- Mitchison, Fry & Fry 2002, pp. 223-224.

- Upham 1842, pp. 230–231.

- Upham 1842, p. 240.

- Upham 1842, pp. 241–242.

- Upham 1842, pp. 242–243.

- Upham 1842, pp. 291–294.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 137 cites Weekly Intelligencer, 11–18 October 1659; Declaration of the officers of the army 27 October 1659; Crate, Original Letters, ii.247

- Ludlow 1894, pp. 137–140.

- Ludlow 1894, pp. 140–141.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 141 cites: Guizot, Richard Cromwell, ii. 267, and the proceedings of the Council of officers on 15 October

- Ludlow 1894, p. 141 cites: A True Narrative, pp. 21, 41; Guizot [Richard Cromwell], ii. 272.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 149 cites: Guizot, Richard Cromwell, ii. 284

- Ludlow 1894, p. 164.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 170.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 178.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 181 cites Narrative of the Proceedings of the Fleet, published in 1659, and reprinted in Penn's Memorials of Sir William Penn, ii. 186

- Ludlow 1894, p. 185.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 192.

- Ludlow 1894, pp. 201–211.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 228 cites: Price, [Mystery and Method of his Majesty's happy restoration, reprinted by Maseres], p.751; cf. Guizot, Richard Cromwell, ii. 371; Carte Ormonde, iv. 51

- Ludlow 1894, p. 246.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 249.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 250.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 259.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 261.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 274.

- Ludlow 1894, pp. 267–278, 301–302.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 267 cites: Mercurius Publicus, 31 May – 7 June 1660

- Ludlow 1894, p. 303.

- Ludlow 1894, p. 288 cites Old Parliamentary History, xxii. 419

- Upham 1842, pp. 371–393.

Sources

- Carlton, Charles (1995). Charles I: The Personal Monarch. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415125659.

- Coward, Barry (1994). The Stuart Age. Longman. ISBN 978-1405859165.

- Gillespie, Raymond (2006). Seventeenth Century Ireland. Gill and McMillon. ISBN 978-0-7171-3946-0.

- Grayling, AC (2017). Democracy and its crisis. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1786072894.

- Gregg, Pauline (1981). King Charles I. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0460044370.

- Harris, Tim (2014). Rebellion: Britain's First Stuart Kings, 1567-1642. OUP. ISBN 978-0199209002.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1968). Charles I. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- House of Commons (1802), "House of Commons Journal Volume 7: 16 March 1660", Journal of the House of Commons Volume=7: 1651–1660, pp. 879–880

- Jessup, Frank W. (2013). Background to the English Civil War: The Commonwealth and International Library: History Division. Elsevier. ISBN 9781483181073.

- Kenyon, J.P. (1978), Stuart England, Penguin Books

- Ludlow, Edmund (1894), Firth, C.H. (ed.), The Memoirs of Edmund Ludlow Lieutenant-General of the Horse in the Army of the Commonwealth of England 1625–1672, 2, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Macloed, Donald (Autumn 2009). "The influence of Calvinism on politics". Theology in Scotland. XVI (2).

- Manganiello, Stephen (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639–1660. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810851009.

- Mitchison, Rosalind; Fry, Peter; Fry, Fiona (2002). A History of Scotland. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138174146.

- Rees, John (2016). The Leveller Revolution. Verso. ISBN 978-1784783907.

- Royle, Trevor (2004). Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638–1660 (2006 ed.). Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.

- Smith, David L. (1999). The Stuart Parliaments 1603–1689. Hodder Education. ISBN 978-0340719916.

- Starky, David (2006). Monarchy: England and her Rulers from the Tudors to the Windsors. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0007247660.

- Upham, Charles Wentworth (1842), Sparks, Jared (ed.), Life of Sir Henry Vane, Fourth Governor of Massachusetts in The Library of American Biography, New York: Harper & Brothers, ISBN 1-115-28802-4

- Wedgwood, CV (1958). The King's War, 1641-1647 (2001 ed.). Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0141390727.

Further reading

- British Civil Wars: The Long Parliament

- British Civil Wars: 1641 Time Line

- British Civil Wars: 1642 Time Line

- Full text of The Triennial Act. 15 February 1641

- Full text of the Act against Dissolving the Long Parliament without its own Consent 11 May 1641

- Full text of the act Abolishing the Star Chamber 5 July 1641

- Full text of the Act Declaring the Illegality of Ship-money 7 August 1641

- Full Text of the Grand Remonstrance, with the Petition accompanying it. 22 November 1641

- Full text of the King's Answer to the Petition Accompanying the Grand Remonstrance 23 December 1641

- Full text of The Solemn League and Covenant 25 September 1643

- Full text of the Ordinance appointing the First Committee of both Kingdoms 16 February 1644

- Full text of the Self-denying Ordinance 4 April 1645

- List of members and their allegiance in the Civil War

- The Tryal of Thomas Earl of Stafford, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland by the Commons then Assembled in Parliament in the name of themselves and of all the Commons in England, 1640, John Rushworth.

.svg.png.webp)