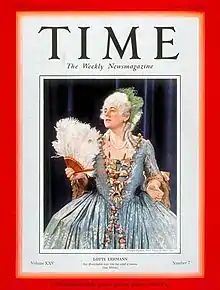

Lotte Lehmann

Charlotte "Lotte" Lehmann (February 27, 1888 – August 26, 1976) was a German soprano who was especially associated with German repertory. She gave memorable performances in the operas of Richard Strauss, Richard Wagner, Ludwig van Beethoven, Puccini, Mozart, and Massenet. The Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, Sieglinde in Die Walküre and the title-role in Fidelio are considered her greatest roles. During her long career, Lehmann also made more than five hundred recordings.[1]

Life and career

Lehmann was born in Perleberg, Province of Brandenburg.

After studying in Berlin with Mathilde Mallinger, she made her debut at the Hamburg Opera in 1910 as a page in Wagner's Lohengrin. In 1914, she gave her debut as Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg at the Vienna Court Opera – the later Vienna State Opera – which she joined in 1916. She quickly established herself as one of the company's brightest stars in roles such as Elisabeth in Tannhäuser and Elsa in Lohengrin.

She created roles in the world premieres of a number of operas by Richard Strauss, including the Composer in Ariadne auf Naxos in 1916 (later she sang the title-role in this opera), the Dyer's Wife in Die Frau ohne Schatten in 1919 and Christine in Intermezzo in 1924. Her other Strauss roles were the title-roles in Arabella (she sang in the Viennese premiere on 21 October 1933, even though her mother had died earlier that day)[2] and in Der Rosenkavalier (earlier in her career, she had also sung the role of Sophie and Octavian; when she finally added the Marschallin to her repertoire, she became the first soprano in history to have sung all three female lead roles in Der Rosenkavalier).

Her Puccini roles at the Vienna State Opera included the title-roles in Tosca, Manon Lescaut, Madama Butterfly, Suor Angelica, Turandot, Mimi in La bohème and Giorgetta in Il tabarro. In her 21 years with the company, Lehmann sang more than fifty different roles at the Vienna State Opera, including Marie/Marietta in Die tote Stadt, the title-roles in La Juive by Fromental Halévy, Mignon by Ambroise Thomas, and Manon by Jules Massenet, Charlotte in Werther, Marguerite in Faust, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin and Lisa in The Queen of Spades.

In the meantime she had made her debut in London in 1914, and from 1924 to 1935 she performed regularly at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden where aside from her famous Wagner roles and the Marschallin she also sang Desdemona in Otello and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. She appeared regularly at the Salzburg Festival from 1926 to 1937, performing with Arturo Toscanini, among other conductors. She also gave recitals there accompanied at the piano by the conductor Bruno Walter.

In August 1936, while in Salzburg, she discovered the Trapp Family Singers, later made famous in the musical The Sound of Music. Lehmann had heard of a villa available for let and as she approached the villa she overheard the family singing in their garden. Insisting the children had a precious gift, she exclaimed that the family had "gold in their throats" and that they should enter the Salzburg Festival contest for group singing the following night. Having regard to the family's aristocratic background the Baron insisted performing in public was out of the question; however Lehmann's fame and genuine enthusiasm persuaded the Baron to relent, leading to their first public performance.[3]

February 18, 1935

In 1930, Lehmann made her American debut in Chicago as Sieglinde in Wagner's Die Walküre. She returned to the United States every season and also performed several times in South America. Before Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Lehmann emigrated to the United States.[4] There, she continued to sing at the San Francisco Opera and the Metropolitan Opera until 1945.

In addition to her operatic work, Lehmann was a renowned singer of lieder, giving frequent recitals throughout her career. She recorded and toured with pianist Ernő Balogh in the 1930s. Beginning with her first recital tour to Australia in 1937, she worked closely with the accompanist Paul Ulanowsky. He remained her primary accompanist for concerts and master classes until her retirement fourteen years later.[5]

She also made a foray into film acting, playing the mother of Danny Thomas in Big City (1948), which also starred Robert Preston, George Murphy, Margaret O'Brien and Betty Garrett.

After her retirement from the recital stage in 1951, Lehmann taught master classes at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, California, which she helped found in 1947.[6] She also gave master classes in New York City's Town Hall (for the Manhattan School of Music), Chicago, London, Vienna, and other cities. For her contribution to the recording industry, Lehmann has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1735 Vine St. However, her first name is misspelled there as "Lottie".

She was a prolific author, publishing a book of poems Verse in Prosa in the early 1920s, a novel, Orplid, mein Land in 1937, which appeared in English as Eternal Flight in 1937, and a book of memoirs, Anfang und Aufstieg (1937), which later appeared as On Wings of Song in the U.K. in 1938 and as Midway in My Song in the U.S. in 1938. She also published volumes on the interpretation of song and the interpretation of opera roles. Later books included Five Operas and Richard Strauss, known as Singing with Richard Strauss in the U.K., a second book of poems in 1969, and Eighteen Song Cycles in 1971, consisting of material drawn largely from earlier works.

Lehmann was an active painter, especially in her retirement. Her painting included a series of twenty-four illustrations in tempera for each song of Schubert's Winterreise.[7]

Lehmann died in 1976 at the age of 88 in Santa Barbara, California. She is interred in the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna.[8] Her headstone is inscribed with a quote from Richard Strauss: "Sie hat gesungen, daß es Sterne rührte." ("She sang such that it moved the stars.")

Personal life

In 1926 Lehmann married Otto Krause, a former officer in the Austrian army and later an insurance executive. They had no children. Krause, who died of tuberculosis in 1939, had four children from a previous marriage. Lehmann never remarried.[9][10]

After Krause's death until her own death in 1976 Lehmann shared a home with Frances Holden (1899–1996), a psychologist who specialised in the study of genius, particularly that of classical musicians. The two women named their Santa Barbara house "Orplid" after the dream island described in Hugo Wolf's art song "Gesang Weylas".[11]

Legacy

- Lehmann helped establish the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara, California, where there is a hall named for her.

- The Lotte Lehmann Concert Hall on the campus of the University of California, Santa Barbara was also named in her honor. She had given many master classes there.

- The Lotte Lehmann Collection at the UCSB Library's Special Collections contains Lehmann's recordings, papers, photos, etc.

- A collection of manuscripts, photos and recordings called the Gary Hickling Collection on Lotte Lehmann is housed at the Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound at Stanford University.

- The bulk of Lehmann's private recordings is held at the Miller Nichols Library Marr Sound Archives at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

- Lehmann's friend Hertha Schuch willed her large collection (now in 18 boxes) of Lehmann recordings, correspondence, photos, etc. to the Austrian Theatre Museum in Vienna (Österreichisches Theatermuseum, Wien).

- The Lotte Lehmann Foundation was established in 1995 to preserve and perpetuate Lotte Lehmann's legacy and at the same time to bring art song into the lives of as many people as possible. It ceased activity in 2011. In 2011, the Lotte Lehmann League developed a website in her honor.[12]

- In her native city, Perleberg, the Lotte Lehmann Akademie was established in her name in 2009. A summer programme for young opera singers wishing to specialise in the German repertoire, the academy's faculty has included Karan Armstrong and Thomas Moser, both former students of Lehmann.[13]

Works

- Eighteen song cycles: studies in their interpretation (London: Cassell, 1971)

- Eternal Flight, translated by Elsa Krauch (NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1937)

- Five operas and Richard Strauss. (New York, Macmillan Co. [1964]

- Midway in my Song: The Autobiography of Lotte Lehmann (NY: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1938)

- More Than Singing: The Interpretation of Songs (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1945)

- My Many Lives (NY: Boosey & Hawkes, 1948)

Recordings

- Great Voices of the Century[14]

Notes

- "Lotte Lehmann Discography", accessed February 21, 2013.

- Tanya Buchdahl Tintner, Out of Time: The Vexed Life of Georg Tintner, p. 29

- Trapp, Maria Augusta (2002). The Story of the Trapp Family Singers. New York: William Morrow. pp. 104–05. ISBN 006000577-7.

- "Lotte Lehmann Misconceptions". Lotte Lehmann League. 2011-04-20. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

- "Paul Ulanowsky: A Life in Music", accessed March 18, 2010

- Greenberg, Robert (26 August 2019). "Music History Monday: Lotte Lehmann". robertgreenbergmusic.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Lee Stern Who is who in music: A complete presentation of the contemporary …1951 ; one, "Der Lindenbaum," can be found on the cover of A Yiddish Winterreise Naxos 8.572256

- "Honorary grave located at Group 32 C, Nr. 49". Viennatouristguide.at. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

- New York Sun (23 January 1939). "Otto Krause Dies Upstate; Lotte Lehmann's Husband Was Insurance Official", p. 19.

- Whitman, Alden (27 August 1976). "Lotte Lehmann Dies at 88; Diva and Lieder Specialist", p. 1. New York Times

- Los Angeles Times (August 25, 1996). "Frances Holden; Studied Psychology of Genius"

- lottelehmannleague.org

- "Lotte Lehmann Akademie". Lottelehmannakademie.de. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- "SCSH 001, SanCtuS Recordings". Sanctusrecordings.com. 2013-03-16. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

Sources

- Nigel Douglas, Legendary Voices (London: Deutsch, 1992)

- Beaumont Glass, Lotte Lehmann: A Life in Opera and Song (Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1988)

- Alan Jefferson, Lotte Lehmann, 1888–1976: A Centenary Biography (London : J. MacRae Books, 1988); German version: Lotte Lehmann: Eine Biographie (1991)

- Michael H. Kater, Never Sang for Hitler: The Life and Times of Lotte Lehmann (NY: Cambridge University Press, 2008)

Further reading

- Kathy H. Brown, "Lotte Lehmann in America: Her Legacy as Artist Teacher" (Missoula, Montana: The College Music Society, 2012)

- Gary Hickling, "Lotte Lehmann & Her Legacy: Volume I - VII“ (Apple iBook, 2015-2017)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lotte Lehmann. |