Turandot

Turandot (/ˈtjʊərəndɒt/ TEWR-ən-dot, Italian: [turanˈdɔt] (![]() listen);[1][2] see below) is an opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini, posthumously completed by Franco Alfano in 1926, and set to a libretto in Italian by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni. Its best-known aria is "Nessun dorma".[3]

listen);[1][2] see below) is an opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini, posthumously completed by Franco Alfano in 1926, and set to a libretto in Italian by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni. Its best-known aria is "Nessun dorma".[3]

| Turandot | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Giacomo Puccini | |

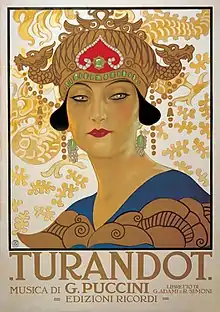

The cover of the score printed by Ricordi | |

| Librettist | |

| Language | Italian |

| Based on | Carlo Gozzi's play Turandot |

| Premiere | |

Though Puccini first became interested in the subject matter when reading Friedrich Schiller's 1801 adaptation,[4] he based his work more closely on the earlier play Turandot (1762) by Count Carlo Gozzi. The original story is one of the seven stories in the epic Haft Peykar; a work by twelfth-century Persian poet Nizami (c. 1141–1209). Nizami aligned his seven stories with the seven days of the week, the seven colors, and the seven planets known in his era. This particular narrative is the story of Tuesday, as told to the king of Iran, Bahram V (r. 420–438), by his companion of the red dome, associated with Mars.[5] In the first line of the story, the protagonist is identified as a Russian princess. The name of the opera is based on Turan-Dokht (daughter of Turan), which is a name frequently used in Persian poetry for Central Asian princesses.

The opera's version of the story is set in China.[6] It involves Prince Calaf, who falls in love with the cold Princess Turandot. In order to obtain permission to marry her, a suitor must solve three riddles. Any single wrong answer will result in the suitor's execution. Calaf passes the test, but Turandot refuses to marry him. He offers her a way out: if she is able to guess his name before dawn the next day, he will accept death. In the original story by Nizami, the princess sets four conditions: firstly "a good name and good deeds", and then the three challenges. As with Madama Butterfly, Puccini strove for a semblance of Asian authenticity (at least to Western ears) by integrating music from the region. Up to eight of the musical themes in Turandot appear to be based on traditional Chinese music and anthems, and the melody of a Chinese song "Mò Li Hūa (茉莉花)", or "Jasmine", became a motif for the princess.[7]

Puccini left the opera unfinished at the time of his death in 1924; Franco Alfano completed it in 1926. The first performance took place at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan on 25 April 1926, conducted by Arturo Toscanini. The performance included only Puccini's music without Alfano's additions. The first performance of the opera as completed by Alfano was performed on the next evening, 26 April, although it is disputed whether the second performance was conducted by Toscanini or by Ettore Panizza.

Origin and pronunciation of the name

Turandot is a Persian word and name that means "daughter of Turan", Turan being a region of Central Asia, formerly part of the Persian Empire. The name of the opera is taken from Persian Turandokht (توراندخت), with dokht being a contraction of dokhtar (daughter); the kh and t are both pronounced.[8] However, the original protagonist in Nizami's story is identified in the first line of the Persian poem as being from Russia. The story is known as the story of the Red Dome among the Seven Domes (Haft Ghonbad) stories in Nizami's Haft Peykar (i.e., the seven figures or beauties).

According to Puccini scholar Patrick Vincent Casali, the final t is silent in the opera's and title character's name, making it sound [turanˈdo]. Soprano Rosa Raisa, who created the title role, said that neither Puccini nor Arturo Toscanini, who conducted the first performances, ever pronounced the final t. Eva Turner, a prominent Turandot, did not pronounce the final t, as television interviews with her attest. Casali also maintains that the musical setting of many of Calaf's utterances of the name makes sounding the final t all but impossible.[9] On the other hand, Simonetta Puccini, the composer's granddaughter and keeper of the Villa Puccini and Mausoleum, has said that the final t must be pronounced. Italo Marchini questioned her about this in 2002. Ms. Puccini said that in Italian the name would be Turandotta. In the Venetian dialect of Carlo Gozzi the final syllables are usually dropped and words end in a consonant, ergo Turandott, as the name has been made Venetian.[10][11]

In 1710, while writing the first biography of Genghis Khan, the French scholar François Pétis de La Croix published a book of tales and fables combining various Asian literary themes. One of his longest and best stories is derived from the history of Mongol princess Khutulun. In his adaptation, however, she bore the title Turandot, meaning "Turkish Daughter", the daughter of Kaidu. Instead of challenging her suitors in wrestling, Pétis de La Croix had her confront them with three riddles. In his more dramatic version, instead of wagering mere horses, the suitor had to forfeit his life if he failed to answer correctly.

Fifty years later, the popular Italian playwright Carlo Gozzi made her story into a drama of a "tigerish woman" of "unrelenting pride". In a combined effort by two of the greatest literary talents of the era, Friedrich von Schiller translated the play into German as Turandot, Prinzessin von China, and Goethe directed it on the stage in Weimar in 1802.

– Jack Weatherford<ref>Jack Weatherford, "The Wrestler Princess", Lapham's Quarterly, 3 September 2010</ref><ref name="schiller" />

Composition history

The story of Turandot was taken from a Persian collection of stories called The Book of One Thousand and One Days[12] (1722 French translation Les Mille et un jours by François Pétis de la Croix – not to be confused with its sister work The Book of One Thousand and One Nights) – in which the character of "Turandokht" as a cold princess is found.[13] The story of Turandokht is one of the best-known tales from de la Croix's translation. The plot respects the classical unities of time, space, and action.

Puccini began working on Turandot in March 1920 after meeting with librettists Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni. In his impatience, he began composition in January 1921, before Adami and Simoni had produced the text for the libretto. Baron Fassini Camossi, the former Italian diplomat to China, gave Puccini a music box that played a number of Chinese melodies. Puccini used three of these in the opera, including the national anthem (heard during the appearance of the Emperor Altoum) and, most memorably, the folk melody "Mo Li Hua" (Jasmine Flower) which is first sung by the children's chorus after the invocation to the moon in Act 1, and becomes a sort of 'leitmotif' for the princess throughout the opera. Puccini commissioned a set of thirteen gongs constructed by the Tronci family specifically for Turandot. Decades later, percussionist Howard Van Hyning of the New York City Opera had been searching for a proper set of gongs and obtained the original set from the Stivanello Costume Company, which had acquired the gongs as the result of winning a bet. In 1987, he bought the gongs for his collection, paying thousands of dollars for the set, which he described as having "colorful, intense, centered, and perfumed" sound qualities.[14]

As with Madama Butterfly, Puccini strove for a semblance of Asian authenticity (at least to Western ears) by using music from the region. Up to eight of the themes used in Turandot appear to be based on traditional Chinese music and anthems, and the melody of a Chinese song named "Mò Li Hūa (茉莉花)", or "Jasmine", is included as a motif for the princess.[7]

By March 1924, Puccini had completed the opera up to the final duet. However, he was dissatisfied with the text of the final duet, and did not continue until 8 October, when he chose Adami's fourth version of the duet text. On 10 October he was diagnosed with throat cancer, and on 24 November he went to Brussels, Belgium for treatment. There he underwent a new and experimental radiation therapy. Puccini and his wife never knew how serious the cancer was, as the prognosis was revealed only to his son. Puccini, however, seems to have had some inkling of the seriousness of his condition since, before leaving for Brussels, he visited Toscanini and begged him, "Don't let my Turandot die".[15] He died of a heart attack on 29 November 1924, when it had seemed that the radium treatment was succeeding. His step-daughter Fosca was in fact joyfully writing a letter to an English friend of the family, Sibyl Seligman, telling her that the cancer was shrinking when she was called to her father's bedside because of the heart attack.[16]

Completion of the score after Puccini's death

When Puccini died, the first two of the three acts were fully composed, including the orchestration. Puccini had composed and fully orchestrated Act Three up until Liù's death and funeral cortege. In the sense of finished music, this was the last music composed by Puccini.[17][18] He left behind 36 pages of sketches on 23 sheets for the end of Turandot. Some sketches were in the form of "piano-vocal" or "short score," including vocal lines with "two to four staves of accompaniment with occasional notes on orchestration."[19] These sketches provided music for some, but not all, of the final portion of the libretto.

Puccini left instructions that Riccardo Zandonai should finish the opera. Puccini's son Tonio objected, and eventually Franco Alfano was chosen to flesh out the sketches after Vincenzo Tommasini (who had completed Boito's Nerone after the composer's death) and Pietro Mascagni were rejected. Puccini's publisher Tito Ricordi II decided on Alfano because his opera La leggenda di Sakùntala resembled Turandot in its setting and heavy orchestration.[20] Alfano provided a first version of the ending with a few passages of his own, and even a few sentences added to the libretto, which was not considered complete even by Puccini. After the severe criticisms by Ricordi and the conductor Arturo Toscanini, he was forced to write a second, strictly censored version that followed Puccini's sketches more closely, to the point where he did not set some of Adami's text to music because Puccini had not indicated how he wanted it to sound. Ricordi's real concern was not the quality of Alfano's work, but that he wanted the end of Turandot to sound as if it had been written by Puccini, and Alfano's editing had to be seamless. Of this version, about three minutes were cut for performance by Toscanini, and it is this shortened version that is usually performed today.

Performance history

The premiere of Turandot was at La Scala, Milan, on Sunday 25 April 1926, one year and five months after Puccini's death. Rosa Raisa held the title role. Tenors Miguel Fleta and Franco Lo Giudice alternated in the role of Prince Calaf in the original production with Fleta singing the role on opening night. It was conducted by Arturo Toscanini. In the middle of act 3, two measures after the words "Liù, poesia!", the orchestra rested. Toscanini stopped and laid down his baton. He turned to the audience and announced: "Qui finisce l'opera, perché a questo punto il maestro è morto" ("Here the opera ends, because at this point the maestro died"). The curtain was lowered slowly. These are the words reported by Eugenio Gara, who was present at the premiere.[21] A reporter for La Stampa recorded the words slightly differently: "Qui finisce l'opera, rimasta incompiuta per la morte del povero Puccini/Here the opera ends, left incomplete by the death of poor Puccini."[22] It is also frequently reported that Toscanini said, more poetically, "Here the Maestro laid down his pen".[23]

A newspaper report published the day before the premiere states that Puccini himself gave Toscanini the suggestion to stop the opera performance at the final notes composed by Puccini:

Poche settimane prima di morire il Maestro, dopo aver fatto sentire l'opera ad Toscanini, esclamò: "Se non riuscirò a condurla a termine, a questo punto verrà qualcuno alla ribalta e dirà: "L'autore ha musicato fin qui, poi è morto". Arturo Toscanini ha raccolto con commozione queste parole e, con la pronta adesione della famiglia di Giacomo Puccini e degli editori, volle che la sera della prima rappresentazione, l'opera apparisse come l'autore la lasciò, con l'angoscia di non poterla finire.

(A few weeks before his death, after having made Toscanini listen to the opera, Puccini exclaimed: "If I don't succeed in finishing it, at this point someone will come to the footlights and will say: 'The author composed until here, and then he died.'" Arturo Toscanini related Puccini's words with great emotion, and, with the swift agreement of Puccini's family and the publishers, decided that the evening of the first performance, the opera would appear as the author left it, with the anguish of being unable to finish).[22]

Two authors believe that the second and subsequent performances of the 1926 La Scala season, which included the Alfano ending, were conducted by Ettore Panizza and Toscanini never conducted the opera again after the first performance.[24] However, in his biography of Toscanini, Harvey Sachs claims that Toscanini did conduct the second and third performances before withdrawing from the production due to nervous exhaustion.[25] A contemporary review of the second performance states that Toscanini was the conductor, taking five curtain calls at the end of the performance.[26]

Turandot quickly spread to other venues: Rome (Teatro Costanzi, 29 April, four days after the Milan premiere), Buenos Aires (Teatro Colón, Claudia Muzio as Turandot Giacomo Lauri Volpi as Calaf, 23 June, less than two months after opening in Milan),[27] Dresden (4 July, in German, with Anne Roselle as Turandot, and Richard Tauber as Calaf, conducted by Fritz Busch), Venice (La Fenice, 9 September), Vienna (14 October; Mafalda Salvatini in the title role), Berlin (8 November), New York (Metropolitan Opera, 16 November), Brussels (La Monnaie, 17 December, in French), Naples (Teatro di San Carlo, 17 January 1927), Parma (12 February), Turin (17 March), London (Covent Garden, 7 June), San Francisco (19 September), Bologna (October 1927), Paris (29 March 1928), Australia 1928, Moscow (Bolshoi Theatre, 1931). Turandot is a staple of the standard operatic repertoire and it appears as number 17 on the Operabase list of the most-performed operas worldwide.[28]

For many years, the government of the People's Republic of China forbade performance of Turandot because they said it portrayed China and the Chinese unfavourably.[29][30] In the late 1990s they relented, and in September 1998 the opera was performed for eight nights as Turandot at the Forbidden City, complete with opulent sets and soldiers from the People's Liberation Army as extras. It was an international collaboration, with director Zhang Yimou as choreographer and Zubin Mehta as conductor. The singing roles saw Giovanna Casolla, Audrey Stottler, and Sharon Sweet as Princess Turandot; Sergej Larin and Lando Bartolini as Calaf; and Barbara Frittoli, Cristina Gallardo-Domâs, and Barbara Hendricks as Liù.

"Nessun dorma", the opera's most famous aria, has long been a staple of operatic recitals. Luciano Pavarotti popularized the piece beyond the opera world in the 1990s following his performance of it for the 1990 World Cup, which captivated a global audience.[31] Both Pavarotti and Plácido Domingo released singles of the aria, with Pavarotti’s reaching number 2 in the UK.[32][33] The Three Tenors performed the aria at three subsequent World Cup Finals, in 1994 in Los Angeles, 1998 in Paris, and 2002 in Yokohama.[31] Many crossover and pop artists have performed and recorded it and the aria has been used in the soundtracks of numerous films.[3]

Alfano's and other versions

The debate over which version of the ending is better is still open.[24] The opera with Alfano's original ending was first recorded by John Mauceri and Scottish Opera (with Josephine Barstow and Lando Bartolini as soloists) for Decca Records in 1990 to great acclaim.[34][35] The first verifiable live performance of Alfano's original ending was not mounted until 3 November 1982, by the Chelsea Opera Group at the Barbican Centre in London. However, it may have been staged in Germany in the early years, since Ricordi had commissioned a German translation of the text and a number of scores were printed in Germany with the full final scene included. Alfano's second ending has been further redacted as well: Turandot's aria "Del primo pianto" was performed at the premiere but cut from the first complete recording; it was eventually restored to most performances of the opera.

From 1976 to 1988 the American composer Janet Maguire, convinced that the whole ending is coded in the sketches left by Puccini, composed a new ending,[36] but this has never been performed.[37] In 2001 Luciano Berio made a new completion sanctioned by Casa Ricordi and the Puccini estate, using Puccini's sketches but also expanding the musical language. It was subsequently performed in the Canary Islands and Amsterdam conducted by Riccardo Chailly, Los Angeles conducted by Kent Nagano, at the Salzburg Festival conducted by Valery Gergiev in August 2002. However, its reception has been mixed.[38][39]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 25 April 1926 (Conductor: Arturo Toscanini) |

|---|---|---|

| Princess Turandot | soprano | Rosa Raisa |

| The Emperor Altoum, her father | tenor | Francesco Dominici |

| Timur, the deposed King of Tartary | bass | Carlo Walter |

| The Unknown Prince (Calaf), his son | tenor | Miguel Fleta |

| Liù,[note 1] a slave girl | soprano | Maria Zamboni |

| Ping, Lord Chancellor | baritone | Giacomo Rimini |

| Pang, Majordomo | tenor | Emilio Venturini |

| Pong, Head chef of the Imperial Kitchen | tenor | Giuseppe Nessi |

| A Mandarin | baritone | Aristide Baracchi |

| The Prince of Persia | tenor | Not named in the original program |

| The Executioner (Pu-Tin-Pao) | silent | Not named in the original program |

| Imperial guards, the executioner's men, boys, priests, mandarins, dignitaries, eight wise men, Turandot's handmaids, soldiers, standard-bearers, musicians, ghosts of suitors, crowd | ||

Synopsis

- Place: Peking, China

- Time: Legendary times

Act 1

In front of the imperial palace

In China, beautiful Princess Turandot will only marry a suitor who can answer three secret riddles. A Mandarin announces the law of the land (Aria – "Popolo di Pechino!" – "People of Peking!"). The Prince of Persia has failed to answer the three riddles, and he is to be beheaded at the next rising moon. As the crowd surges towards the gates of the palace, the imperial guards brutally repulse them, causing a blind old man to be knocked to the ground. The old man's slave-girl, Liù, cries out for help. A young man hears her cry and recognizes that the old man is his long-lost father, Timur, the deposed king of Tartary. The young Prince of Tartary is overjoyed at seeing Timur alive, but still urges Timur to not speak his name because he is afraid that the Chinese rulers, who have conquered Tartary, may kill or harm them. Timur then tells his son that, of all his servants, only Liù has remained faithful to him. When the Prince asks her why, she tells him that once, long ago in the palace, the Prince had smiled at her (Trio with chorus – The crowd, Liù, Prince of Tartary, Timur: "Indietro, cani!" – "Back, dogs!").

The moon rises, and the crowd's cries for blood dissolve into silence. The doomed Prince of Persia, who is on his way to be executed, is led before the crowd. The young Prince is so handsome and kind that the crowd and the Prince of Tartary decide that they want Turandot to act compassionately, and they beg Turandot to appear and spare his life (Aria – The crowd, Prince of Tartary: "O giovinetto!" – "O youth!"). She then appears, and with a single imperious gesture, orders the execution to continue. The Prince of Tartary, who has never seen Turandot before, falls immediately in love with her, and joyfully cries out Turandot's name three times, foreshadowing the riddles to come. Then the Prince of Persia cries out Turandot’s name one final time, mirroring the Prince of Tartary. The crowd, horrified, screams out one final time and the Prince of Persia is beheaded.

The Prince of Tartary is dazzled by Turandot's beauty. He is about to rush towards the gong and to strike it three times – the symbolic gesture of whoever wishes to attempt to solve the riddles so that he can marry Turandot – when the ministers Ping, Pang, and Pong appear. They urge him cynically to not lose his head for Turandot and to instead go back to his own country ("Fermo, che fai?"). Timur urges his son to desist, and Liù, who is secretly in love with the Prince, pleads with him not to attempt to solve the riddles ("Signore, ascolta!" – "Lord, hear!"). Liù's words touch the Prince's heart. He begs Liù to make Timur's exile more bearable by not abandoning Timur if the Prince fails to answer the riddles ("Non piangere, Liù" – "Do not cry, Liù"). The three ministers, Timur, and Liù then try one last time to stop the Prince ("Ah! Per l'ultima volta!" – "Ah! For the last time!") from attempting to answer the riddles, but he refuses to heed their advice.

He calls Turandot's name three times, and each time Liù, Timur, and the ministers reply, "Death!" and the crowd declares, "We're already digging your grave!" Rushing to the gong that hangs in front of the palace, the Prince strikes it three times, declaring himself to be a suitor. From the palace balcony, Turandot accepts his challenge, as Ping, Pang, and Pong laugh at the Prince's foolishness.

Act 2

Scene 1: A pavilion in the imperial palace. Before sunrise

Ping, Pang, and Pong lament their place as ministers, poring over palace documents and presiding over endless rituals. They prepare themselves for either a wedding or a funeral (Trio – Ping, Pang, Pong: "Ola, Pang!"). Ping suddenly longs for his country house in Honan, with its small lake surrounded by bamboo. Pong remembers his grove of forests near Tsiang, and Pang recalls his gardens near Kiu. The three share their fond memories of their lives away from the palace (Trio – Ping, Pang, Pong: "Ho una casa nell'Honan" – "I have a house in Honan"). They turn their thoughts back to how they have been accompanying young princes to their deaths. As the palace trumpet sounds, the ministers ready themselves for another spectacle as they await the entrance of their Emperor.

Scene 2: The courtyard of the palace. Sunrise

The Emperor Altoum, father of Turandot, sits on his grand throne in his palace. Weary of having to judge his isolated daughter's sport, he urges the Prince to withdraw his challenge, but the Prince refuses (Aria – Altoum, the Prince: "Un giuramento atroce" – "An atrocious oath"). Turandot enters and explains ("In questa reggia" – "In this palace") that her ancestress of millennia past, Princess Lo-u-Ling, reigned over her kingdom "in silence and joy, resisting the harsh domination of men" until she was raped and murdered by an invading foreign prince. Turandot claims that Lo-u-Ling now lives in her, and out of revenge, Turandot has sworn to never let any man wed her. She warns the Prince to withdraw but again he refuses. The Princess presents her first riddle: "Straniero, ascolta!" – "What is born each night and dies each dawn?" The Prince correctly replies, Speranza – "Hope." The Princess, unnerved, presents her second riddle ("Guizza al pari di fiamma" – "What flickers red and warm like a flame, but is not fire?") The Prince thinks for a moment before replying, Sangue – "Blood". Turandot is shaken. The crowd shouted at the Prince, provoking Turandot's anger. She presents her third riddle ("Gelo che ti da foco" – "What is ice which gives you fire and which your fire freezes still more?"). He proclaims, "It is Turandot! Turandot!"

The crowd roars for the triumphant Prince. Turandot throws herself at her father's feet and pleads with him not to leave her to the Prince's mercy. The Emperor insists that an oath is sacred and that it is Turandot's duty to wed the Prince (Duet – Turandot, Altoum, the Prince: "Figlio del cielo"). She cries out in despair, "Will you take me by force? (Mi porterai con la forza?) The Prince stops her, saying that he has a riddle for her: "You do not know my name. Tell me my name before sunrise, and at dawn, I will die." Turandot accepts. The Emperor then declares that he hopes that he will be able to call the Prince his son when the sun next rises.

Act 3

Scene 1: The palace gardens. Night

In the distance, heralds call out Turandot's command: "Cosi comanda Turandot" – "This night, none shall sleep in Peking! The penalty for all will be death if the Prince's name is not discovered by morning". The Prince waits for dawn and anticipates his victory: "Nessun dorma" – "Let no one sleep!"

Ping, Pong, and Pang appear and offer the Prince women and riches if he will only give up Turandot ("Tu che guardi le stelle"), but he refuses. A group of soldiers then drag in Timur and Liù. They have been seen speaking to the Prince, so they must know his name. Turandot enters and orders Timur and Liù to speak. The Prince feigns ignorance, saying they know nothing. But when the guards begin to treat Timur harshly, Liù declares that she alone knows the Prince's name, but she will not reveal it. Ping demands the Prince's name, and when Liù refuses to say it, she is tortured. Turandot is clearly taken aback by Liù's resolve and asks Liù who or what gave her such a strong resolve. Liù answers, "Princess, love!" ("Principessa, amore!"). Turandot demands that Ping tear the Prince's name from Liù, and Ping orders Liù to be tortured even more. Liù counters Turandot ("Tu che di gel sei cinta" – "You who are encircled by ice"), saying that Turandot too will learn the exquisite joy of being guided by caring and compassionate love.[note 2] Having spoken, Liù seizes a dagger from a soldier's belt and stabs herself. As she staggers towards the Prince and falls dead, the crowd screams for her to speak the Prince's name. Since Timur is blind, he must be told about Liù's death, and he cries out in anguish. When Timur warns that the gods will be offended by Liù's death, the crowd becomes subdued, very afraid and ashamed. The grieving Timur and the crowd follow Liù's body as it is carried away. Everybody departs, leaving the Prince and Turandot alone. He reproaches Turandot for her cruelty (Duet – The Prince, Turandot: "Principessa di morte" – "Princess of death"), then takes her in his arms and kisses her in spite of her resistance.[note 3]

The Prince tries to persuade Turandot to love him. At first, she feels disgusted, but after he kisses her, she feels herself becoming more ardently desiring to be held and compassionately loved by him. She admits that ever since she met the Prince, she realized she both hated and loved him. She asks him to ask for nothing more and to leave, taking his mystery with him. The Prince, however, then reveals his name: "Calaf, son of Timur – Calaf, figlio di Timur", thereby placing his life in Turandot's hands. She can now destroy him if she wants (Duet – Turandot, Calaf: "Del primo pianto").

Scene 2: The courtyard of the palace. Dawn

Turandot and Calaf approach the Emperor's throne. She declares that she knows the Prince's name: ("Diecimila anni al nostro Imperatore!") – "It is ... love!" The crowd sings and acclaims the two lovers ("O sole! Vita! Eternità").

Critical response

While long recognised as the most tonally adventurous of Puccini's operas,[41] Turandot has also been considered a flawed masterpiece, and some critics have been hostile. Joseph Kerman states that "Nobody would deny that dramatic potential can be found in this tale. Puccini, however, did not find it; his music does nothing to rationalize the legend or illuminate the characters."[42] Kerman also wrote that while Turandot is more "suave" musically than Puccini's earlier opera, Tosca, "dramatically it is a good deal more depraved."[43] However, Sir Thomas Beecham once remarked that anything that Joseph Kerman said about Puccini "can safely be ignored".[44]

Some of this criticism is possibly due to the standard Alfano ending (Alfano II), in which Liù's death is followed almost immediately by Calaf's "rough wooing" of Turandot, and the "bombastic" end to the opera. A later attempt at completing the opera was made, with the co-operation of the publishers, Ricordi, in 2002 by Luciano Berio. The Berio version is considered to overcome some of these criticisms, but critics such as Michael Tanner have failed to be wholly convinced by the new ending, noting that the criticism by the Puccini advocate Julian Budden still applies: "Nothing in the text of the final duet suggests that Calaf's love for Turandot amounts to anything more than a physical obsession: nor can the ingenuities of Simoni and Adami's text for 'Del primo pianto' convince us that the Princess's submission is any less hormonal."[45]

Ashbrook and Powers consider it was an awareness of this problem – an inadequate buildup for Turandot's change of heart, combined with an overly successful treatment of the secondary character (Liù) – which contributed to Puccini's inability to complete the opera.[24] Another alternative ending, written by Chinese composer Hao Wei Ya, has Calaf pursue Turandot but kiss her tenderly, not forcefully; and the lines beginning "Del primo pianto" (Of the first tears) are expanded into an aria where Turandot tells Calaf more fully about her change of heart.[46][47][48]

Concerning the compelling believability of the self-sacrificial Liù character in contrast to the two mythic protagonists, biographers note echoes in Puccini's own life. He had had a servant named Doria, whom his wife accused of sexual relations with Puccini. The accusations escalated until Doria killed herself – though the autopsy revealed she died a virgin. In Turandot, Puccini lavished his attention on the familiar sufferings of Liù, as he had on his many previous suffering heroines. However, in the opinion of Father Owen Lee, Puccini was out of his element when it came to resolving the tale of his two allegorical protagonists. Finding himself completely outside his normal genre of verismo, he was incapable of completely grasping and resolving the necessary elements of the mythic, unable to "feel his way into the new, forbidding areas the myth opened up to him"[49] – and thus unable to finish the opera in the two years before his unexpected death.

Instrumentation

Turandot is scored for three flutes (the third doubling piccolo), two oboes, one English horn, two clarinets in B-flat, one bass clarinet in B-flat, two bassoons, one contrabassoon, two onstage Alto saxophones in E-flat; four French horns in F, three trumpets in F, three tenor trombones, one contrabass trombone, six onstage trumpets in B-flat, three onstage trombones, and one onstage bass trombone; a percussion section with timpani, cymbals, gong, one triangle, one snare drum, one bass drum, one tam-tam, one glockenspiel, one xylophone, one bass xylophone, tubular bells, tuned Chinese gongs,[50] one onstage wood block, one onstage large gong; one celesta, one pipe organ; two harps and strings.

Recordings

Notes

- Note that the grave accent (`) in the name Liù is not a pinyin tone mark indicating a falling tone, but an Italian diacritic that marks stress, indicating that the word is pronounced [ˈlju] or [liˈu] rather than [ˈliːu]. If the name is analyzed as an authentic Mandarin-language name, it likely to be one of the several characters pronounced Liù (with different respective tones) that are commonly used as surnames: 刘 Liú [ljôu] or 柳 Liǔ [ljòu]. A translation of the song guide hosted by the National Taiwan University refers to her as 柳兒 Liǔ ér.

- The words of that aria were actually written by Puccini. Waiting for Adami and Simoni to deliver the next part of the libretto, he wrote the words and when they read them, they decided that they could not better them.[40]

- Here Puccini's work ends. The remainder of the music for the premiere was completed by Franco Alfano.

References

Citations

- Bruno Migliorini (ed.). "Turandot". Dizionario italiano multimediale e multilingue d'ortografia e di pronunzia (in Italian). Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Luciano Canepari. "Turandot". Dizionario di pronuncia italiana online (in Italian). Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Dalley, Jan (6 November 2015). "The Life of a Song: 'Nessun Dorma'". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- Turandot, Prinzessin von China by Friedrich Schiller at Project Gutenberg. Freely translated from Schiller by Sabilla Novello: Turandot: The Chinese Sphinx by Friedrich Schiller at Project Gutenberg.

- Nizami (21 August 2015). Haft Paykar: A Medieval Persian Romance. Hackett Publishing Company, Incorporated. p. xviii. ISBN 978-1-62466-446-5.

- Turandot's Homecoming: Seeking the Authentic Princess of China in a New Contest of Riddles, Master of Music thesis by Ying-Wei Tiffany Sung, Graduate College of Bowling Green State University, August 2010

- Ashbrook & Powers 1991, Chapter 4.

- "To pronounce the 't' or not when it comes to Turando". The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- Casali, Patrick Vincent (July 1997). "The Pronunciation of Turandot: Puccini's Last Enigma". The Opera Quarterly. 13 (4): 77–91. doi:10.1093/oq/13.4.77. ISSN 0736-0053.

- Carner, Mosco (2011). John, Nicholas (ed.). Turandot – Opera Guide. Oneworld Classics. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-7145-4428-1.

- Kurtzman, Neil (22 December 2008). "Turandot Without the T". Medicine-Opera.com. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- based on a story by the Persian poet Nizami Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Karl Gustav Vollmoeller, Turandot, Princess of China: A Chinoiserie in Three Acts, 1913, online at manybooks.net. Retrieved 8 July 2011

- "Howard Van Hyning, Percussionist and Gong Enthusiast, Dies at 74" by Margalit Fox, The New York Times, 8 November 2010. Accessed 9 November 2010.

- Carner 1958, p. 403.

- Carner 1958, p. 417.

- Fisher, Burton D. (2007). Puccini Companion: The Glorious Dozen: Turandot. Opera Journeys Publishing. p. 24.

- Ashbrook, William (1985). The Operas of Puccini. New York: Cornell University Press by arrangement with Oxford University Press. p. 224.

- Ashbrook & Powers 1991, p. 224

- Turandot: Concert Opera Boston

- Ashbrook & Powers 1991, pp. 126–32

- "La prima rappresentazione di Turandot". La Stampa. 25 April 1926.

- Fiery, Ann; Malone, Peter (2003). At the Opera: Tales of the Great Operas. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 218. ISBN 0-8118-2774-7.

- Ashbrook & Powers 1991, pp. 143, 154

- Sachs 1993, p. 179.

- "La seconda di Turandot, il finale del M. Alfano". La Stampa. 28 April 1926.

- Turandot performance history", Teatro Colón

- "Opera Statistics". Operabase. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- "Banned in China" Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, operacarolina.org

- "Banned in China because officials believed it portrays the country negatively", princeton.edu

- The Music Industry Handbook. Routledge. 2016. p. 219.

- "Official Charts (UK) – Luciano Pavarotti".

- "Official Charts (UK) – Placido Domingo".

- Scottish Opera Chorus, Barstow (1 January 1990). Josephine Barstow: Opera Finales. Decca CD DDD 0289 430 2032 9 DH.

- "Josephine Barstow sings Opera Finales". Gramophone. Mark Allen Group. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Maguire, Janet (1990). "Puccini's Version of the Duet and Final Scene of Turandot". The Musical Quarterly. 74 (3): 319–359. doi:10.1093/mq/74.3.319. JSTOR 741936.

- Burton, Deborah (2013). "The Puccini Code". Rivista di Analisi e Teoria Musicale. 19 (2): 7–32.

- Tommasini, Anthony (22 August 2002). "Critic's Notebook; Updating Turandot, Berio Style". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- Inverne, James (18 August 2002). "Beginning of the End". Time. Retrieved 30 November 2012.(subscription required)

- Colin Kendell, The Complete Puccini, Amberley Publishing 2012

- Jonathan Christian Petty and Marshall Tuttle, "Tonal Psychology in Puccini's Turandot" Archived 21 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Korean Studies, University of California, Berkeley and Langston University, 2001

- Kerman 1988, p. 206.

- Kerman 1988, p. 205.

- Carner 1958, p. 460.

- Tanner, Michael, "Hollow swan-song", The Spectator, 23 March 2003.

- Chinese Composer Gives Turandot a Fresh Finale, NPR's All Things Considered, April 29, 2008.

- A Princess Comes Home: Ken Smith explores how Turandot became China's national opera. Opera magazine, no date.

- "She (the princess) pledges to thwart any attempts of suitors because of an ancestor's abduction by a prince and subsequent death. She is not born cruel and is finally conquered by love. I will try to make Turandot more understandable and arouse the sympathy of Chinese audiences for her." Hao Wei Ya, A Princess Re-Born, China Daily February 19, 2008.

- Lee, Father Owen. "Turandot: Father Owen Lee Discusses Puccini's Turandot." Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Metropolitan Opera Radio Broadcast Intermission Feature, 4 March 1961.

- Blades, James, Percussion instruments and their history, Bold Strummer, 1992, p. 344. ISBN 0-933224-61-3

Sources

- Ashbrook, William; Powers, Harold (1991). Puccini's 'Turandot': the end of the great tradition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02712-9.

- Carner, Mosco (1958). Puccini: a Critical Biography. Gerald Duckworth.

- Kerman, Joseph (1988) [1956]. Opera as Drama (new and revised ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520062740.

- Sachs, Harvey (1993). Toscanini. Robson. ISBN 0-86051-858-2.

Further reading

- Lo, Kii-Ming, »Turandot« auf der Opernbühne, Frankfurt/Bern/New York (Peter Lang) 1996, ISBN 3-631-42578-3.

- Maehder, Jürgen and Sylvano Bussotti, Turandot, Pisa: Giardini, 1983.

- Maehder, Jürgen, "Puccini's Turandot – A Fragment", in Nicholas John (ed.), Turandot, London: John Calder / New York: Riverrun, 1984, pp. 35–53.

- Maehder, Jürgen, "La trasformazione interrotta della principessa. Studi sul contributo di Franco Alfano alla partitura di Turandot", in Jürgen Maehder (ed.), Esotismo e colore locale nell'opera di Puccini, Pisa (Giardini) 1985, pp. 143–170.

- Maehder, Jürgen, "Studi sul carattere di frammento della Turandot di Giacomo Puccini", in Quaderni Pucciniani 2/1985, Milano: Istituto di Studi Pucciniani, 1986, pp. 79–163.

- Maehder, Jürgen, Turandot-Studien, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Beiträge zum Musiktheater VI, season 1986/87, pp. 157–187.

- Maehder, Jürgen (with Lo, Kii-Ming), Puccini's Turandot – Tong hua, xi ju, ge ju, Taipei (Gao Tan Publishing) 1998, 287 pp.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turandot (Puccini). |

- Turandot: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto, Arena di Verona (in Italian)

- Libretto, Italian/English side-by-side

- Recordings of Turandot

- Finale of Turandot on YouTube, from Metropolitan Opera Live in HD 2009

- Berio ending of Turandot on YouTube, De Nederlandse Opera 2010