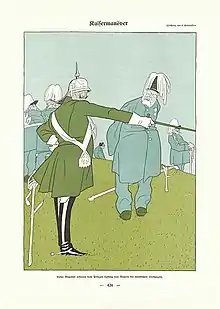

Ludwig III of Bavaria

Ludwig III (Ludwig Luitpold Josef Maria Aloys Alfried; 7 January 1845 – 18 October 1921) was the last king of Bavaria, reigning from 1913 to 1918. He served as regent and de facto head of state from 1912 to 1913, ruling for his cousin, Otto. After the Bavarian parliament passed a law allowing him to do so, Ludwig deposed Otto and assumed the throne himself. He led Bavaria into World War I, and lost his throne along with the other rulers of the German states at the end of the war.

| Ludwig III | |

|---|---|

The King c. 1910s | |

| King of Bavaria | |

| Reign | 5 November 1913 – 13 November 1918 |

| Predecessor | Otto |

| Successor | Monarchy abolished |

| Prime Ministers | |

| Born | 7 January 1845 Munich, Bavaria |

| Died | 18 October 1921 (aged 76) Sárvár, Hungary |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Maria Theresia of Austria-Este |

| Issue | Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria Adelgunde, Princess of Hohenzollern Princess Maria, Duchess of Calabria Prince Karl Prince Franz Mathilde, Princess Ludwig of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Prince Ludwig-Leonhart Princess Hildegarde Princess Notburga Wiltrud, Duchess of Urach Princess Helmtrud Princess Dietlinde Gundelinde, Countess of Preysing-Lichtenegg-Moos |

| House | Wittelsbach |

| Father | Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria |

| Mother | Archduchess Augusta of Austria |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Early life

Ludwig was born in Munich, the eldest son of Prince Luitpold of Bavaria and of his wife, Archduchess Augusta of Austria (daughter of Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany). He was a descendant of both Louis XIV of France and William the Conqueror. Hailing from Florence, Augusta always spoke in Italian to her four children. Ludwig was named after his grandfather, King Ludwig I of Bavaria.

Ludwig spent his first years living in the Electoral rooms of the Munich Residenz and in the Wittelsbacher Palace. From 1852 to 1863, he was tutored by Ferdinand von Malaisé. When he was ten years old, the family moved to the Leuchtenberg Palace.

In 1861 at the age of sixteen, Ludwig began his military career when his uncle, King Maximilian II of Bavaria, gave him a commission as a lieutenant in the 6th Jägerbattalion. A year later, he entered the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, where he studied law and economics. When he was eighteen, he automatically became a member of the Senate of the Bavarian Legislature as a prince of the royal house.

In 1866, Bavaria was allied with the Austrian Empire in the Austro-Prussian War. Ludwig held the rank of Oberleutnant. He was wounded at the Battle of Helmstedt, taking a bullet in his thigh. The incident contributed to the fact that he was rather averse to the military. He received the Knight's Cross 1st Class of the Bavarian Military Merit Order.

Marriage and children

In June 1867, Ludwig visited Vienna to attend the funeral of his cousin, Archduchess Mathilda of Austria (daughter of his father's sister Princess Hildegard of Bavaria). While there, Ludwig met Mathilde's eighteen-year-old step-cousin Maria Theresia, Archduchess of Austria-Este, the only daughter of the late Archduke Ferdinand Karl Viktor of Austria-Este (1821–1849) and his wife Archduchess Elisabeth Franziska of Austria (1831–1903), and they married on 20 February 1868 at St. Augustine's Church in Vienna.

Until 1862, Ludwig's uncle had reigned as King Otto I of Greece. Although Otto had been deposed, Ludwig was still in line of succession to the Greek throne. Had he ever succeeded, this would have required that he renounce his Roman Catholic faith and become Greek Orthodox. Maria Theresa's uncle, Duke Francis V of Modena, was a staunch Roman Catholic. He required that as part of the marriage agreement Ludwig renounce his rights to the throne of Greece, and so ensure that his children would be raised Roman Catholic. In addition, the 1843 Greek Constitution forbade the Greek sovereign to be simultaneously ruler of another country. Consequently, Ludwig's younger brother Leopold technically succeeded upon their father's death to the rights of the deposed Otto I, King of Greece.

By his marriage, Ludwig became a wealthy man. Maria Theresa had inherited large properties from her father. She owned the estate of Sárvár in Hungary and the estate of Eiwanowitz in Moravia (now Ivanovice na Hané in the Czech Republic). The income from these estates enabled Ludwig to purchase an estate at Leutstetten in Bavaria. Over the years, Ludwig expanded the Leutstetten estate until it became one of the largest and most profitable in Bavaria. Ludwig was sometimes derided as Millibauer (dairy farmer) due to his interest in agriculture and farming.

Although they maintained a residence in Munich at the Leuchtenberg Palace, Ludwig and Maria Theresa lived mostly at Leutstetten. They had an extremely happy and devoted marriage which resulted in thirteen children:

- Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria (18 May 1869-2 August 1955), married Duchess Marie Gabriele in Bavaria on 10 August 1900. They had four children. He remarried Princess Antonia of Luxembourg on 7 April 1921. They had six children.

- Princess Adelgunde of Bavaria (17 October 1870-4 January 1958) married Prince Wilhelm of Hohenzollern on 20 January 1915.

- Maria Ludwiga, Princess of Bavaria (6 July 1872-10 June 1954) married Prince Ferdinand Pius of Bourbon-Two Sicilies on 31 May 1897. They have six children.

- Karl, Prince of Bavaria (1 April 1874-9 May 1927)

- Franz, Prince of Bavaria (10 October 1875-25 January 1957) married Princess Isabella Antonie of Croÿ on 12 July 1912

- Princess Mathilde of Bavaria (17 August 1877-6 August 1906) married Prince Ludwig of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on 1 May 1900. They have two children.

- Prince Wolfgang of Bavaria (2 July 1879 - 31 January 1895)

- Princess Hildegard of Bavaria (5 March 1881 - 2 February 1948)

- Princess Notburga of Bavaria (19 March 1883 - 24 March 1883)

- Princess Wiltrud of Bavaria (10 November 1884 - 28 March 1975), married Wilhelm, Duke of Urach on 26 November 1924.

- Princess Helmtrud of Bavaria (22 March 1886 - 23 June 1977)

- Princess Dietlinde of Bavaria (2 January 1888 - 15 February 1889)

- Princess Gundelinde, Princess of Bavaria (26 August 1891 - 16 August 1983), married Count Johann Georg of Preysing-Lichtenegg-Moos on 23 February 1919. They have two children.

- Count Johann Kaspar of Preysing-Lichtenegg-Moos (19 Dececember 1919 - 14 February 1940)

- Countess Maria Theresia of Preysing-Lichtenegg-Moos (23 March 1922 - 14 September 2003), married Ludwig, Count von und zu Arco-Zinneberg on 25 January 1940. They had one son. She remarried to Ludwig's brother, Ulrich Philipp Count von und zu Arco-Zinneberg, on 26 September 1943. They had two sons.

- Rupprecht-Maximilian Count von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (b. 14 January 1941) married Katharina, Countess Henckel von Donnersmarck on 11 July 1968. They have two children.

- Alois Maximilian Count von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (b. 5 June 1970)

- Isabella-Gabriela Countess von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (b. 5 December 1973)

- Ludwig Count von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (1944-1944)

- Riprand Count von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (b. 25 July 1955) married Archduchess Maria Beatrice of Austria on 31 March 1980. They have six daughters.

- Countess Anna Theresa von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (born 1981) married Colin McKenzie on 29 September 2018.

- Countess Margherita von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (born 1983)

- Countess Olympia von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (born 1988) married Jean-Christophe, Prince Napoléon on 17 October 2019.

- Countess Maximiliana von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (born 1990)

- Countess Marie Gabrielle von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (born 1992)

- Countess Giorgiana von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (born 1997)

- Rupprecht-Maximilian Count von und zu Arco-Zinneberg (b. 14 January 1941) married Katharina, Countess Henckel von Donnersmarck on 11 July 1968. They have two children.

On the death of her uncle Francis in 1875, Maria Theresa inherited his Jacobite claim to the thrones of England and Scotland, and is called either Queen Mary IV and III or Queen Mary III by Jacobites.

Service and politics

Throughout his life, Ludwig took a great interest in agriculture. From 1868, he was the Honorary President of the Central Committee of the Bavarian Agricultural Society. In 1875, he bought Leutstetten Castle and made it a model farm. He was also very interested in technology, particularly water power. In 1891 at his initiation, the Bavarian Canal Society was established. In 1896 Prince Ludwig was appointed honorary member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences.

As a prince of the royal house he was automatically a member of the Senate of the Bavarian Legislature; there he was a great supporter of the direct right to vote. Since 23 June 1863 already, Ludwig had been a member of the Chamber of the Reichsräte. In 1870 he voted as a member of the Reichsrat for the acceptance of the November treaties to join the North German Confederation. In 1871 he ran unsuccessfully for the first Reichstag elections as a candidate of the Bavarian Patriot Party. In 1906 he supported the Bavarian electoral reform, which the SPD founder August Bebel praised: "The German people, if the Kaiser were to be chosen from one of the German princes, would presumably elect Wittelsbach Ludwig and not Prussia's Wilhelm."

Regent of Bavaria

On 12 December 1912, Ludwig's father Luitpold died. Luitpold had been an active participant in the deposition of his nephew, King Ludwig II, and had also acted as Prince Regent for his other nephew, King Otto. Although Otto had nominally been king since 1886, he had been under medical supervision since 1883 and it had long been understood that he would never be mentally capable of actively reigning. Ludwig III immediately succeeded his father as regent.

Almost immediately, certain elements in the press and other groups in society called for Ludwig to take the throne himself. The Bavarian Legislature was not, however, currently in session, and did not meet until 29 September 1913. On 4 November 1913, the Legislature amended the constitution of Bavaria to include a clause specifying that if a regency for reasons of incapacity had lasted for ten years with no prospect of the king ever being able to reign, the regent could proclaim the end of the regency and assume the crown himself, with such action to be ratified by the Legislature. The amendment received broad party support in the Lower Chamber where it was carried by a vote of 122 in favour, and 27 against. In the Senate there were only six votes against the amendment. The next day, 5 November 1913, Ludwig proclaimed the end of the regency, deposed his cousin and proclaimed his own reign as Ludwig III. The Legislature duly ratified this action, and Ludwig took his oath on 8 November.

The constitutional amendment of 1913 brought a determining break in the continuity of the king's rule in the opinion of historians, particularly as this change had been granted by the Landtag as a House of Representatives. Historians believe this marked a definitive step from constitutional monarchy to parliamentary monarchy. Bavaria had already taken a step toward full parliamentary government a year earlier, when Georg von Hertling headed the first government that depended on a majority in the legislature.

King of Bavaria

Ludwig's short reign was conservative and influenced by the Catholic encyclical Rerum novarum. Prime Minister Georg von Hertling, appointed by Luitpold in 1912, remained in office. Also as King Ludwig lived in the Wittelsbacher Palais rather than in the Munich Residenz.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914 Ludwig sent an official dispatch to Berlin to express Bavaria's solidarity. Later Ludwig even claimed annexations for Bavaria (Alsace and the city of Antwerp in Belgium, to receive an access to the sea). His hidden agenda was to maintain the balance of power between Prussia and Bavaria within the German Empire after a victory.

A spurious story holds that, a day or two after Germany's declaration of war,[1] Ludwig received a petition from a 25-year-old Austrian, asking for permission to join the Bavarian Army. The petition was promptly granted, and Adolf Hitler thereupon joined the Bavarian Army, eventually settling into the 16th Reserve Bavarian Infantry Regiment, where he served the remainder of the war. However, this account is based on Hitler's recollections in Mein Kampf. Historian Ian Kershaw holds that Hitler's story is simply not credible on its face, due to the remarkable bureaucratic effort it would have required to attend to this minor matter during days of extreme crisis. Kershaw suggests that bureaucratic error, rather than bureaucratic efficiency, was responsible for Hitler's enlistment; indeed, as a national of an allied country, he should have been sent to Austria for service in that army. Based on Bavarian government investigations in 1924, the more likely scenario in Kershaw's view is that Hitler applied for enlistment, along with thousands of other youths, on or about 5 August 1914, was initially turned away because the authorities were overwhelmed with applicants and had no place to assign him, and eventually was recalled to serve in the 2nd Infantry Regiment (2nd Battalion), before being assigned to Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 (the List Regiment), which was principally made up of raw recruits.[2][3]

In 1917, when Germany's situation had gradually worsened due to World War I, Hertling became German Chancellor and Prime Minister of Prussia and Otto Ritter von Dandl was made Minister of State of the Royal Household and of the Exterior and President of the Council of Ministers on 11 November 1917, a title equivalent to Prime Minister of Bavaria. Accused of showing blind loyalty to Prussia, Ludwig became increasingly unpopular during the war. As the war drew to a close, the German Revolution broke out in Bavaria.

Already discussed since September 1917, on 2 November 1918, an extensive constitutional reform was established by an agreement between the royal government and all parliamentary groups, which, among other things, envisaged the introduction of proportional representation. Ludwig III, approved on the same day the transformation of the constitutional into a parliamentary monarchy. For the first time on November 3, 1918, initiated by the USPD, a thousand people gathered to protest on the Theresienwiese for peace and demanded the release of detained leaders. On 7 November 1918, Ludwig fled from the Residenz Palace in Munich with his family and took up residence in Schloss Anif, near Salzburg, for what he hoped would be a temporary stay. He was the first of the monarchs in the German Empire to be deposed. The next day, the People's State of Bavaria was proclaimed.

On 12 November 1918, a day after the Armistice, Prime Minister Dandl went to Schloss Anif to see the King. Ludwig gave Dandl the Anif declaration (Anifer Erklärung) in which he released all government officials, soldiers and civil officers from their oath of loyalty to him. He also stated that as a result of recent events, he was "no longer in a position to lead the government." The declaration was published by the newly formed republican government of Kurt Eisner when Dandl returned to Munich the next day. Ludwig's declaration was not a statement of abdication, as Dandl had demanded. However, Eisner's government interpreted it as such and added a statement that Ludwig and his family were welcome to return to Bavaria as private citizens as long as they did not act against the "people's state." This statement effectively dethroned the Wittelsbachs and ended the family's 738-year rule over Bavaria.[4]

Final years

Ludwig III returned to Bavaria. His wife, Maria Theresia, died 3 February 1919 at Wildenwart Castle/Chiemgau.

In February 1919, Eisner was assassinated; fearing that he might be the victim of a counter-assassination, Ludwig fled to Hungary, later moving on to Liechtenstein and Switzerland. He returned to Bavaria in April 1920 and lived at Wildenwart Castle again. There he remained until September 1921 when he took a trip to his castle Nádasdy in Sárvár in Hungary. He died there on 18 October.

On 5 November 1921, Ludwig's body was returned to Munich together with that of his wife. In spite of fears a state funeral might spark a move to restore the monarchy, the pair were honored with one in front of the royal family, Bavarian government, military personnel, and an estimated 100,000 spectators. Burial was in the crypt of the Munich Frauenkirche alongside their royal ancestors. Prince Rupprecht did not wish to use the occasion of the passing of his father to reestablish the monarchy by force, preferring to do so by legal means. Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber, Archbishop of Munich, in his funeral speech, made a clear commitment to the monarchy while Rupprecht only declared that he had stepped into his birthright.[5]

Honours

.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Bavaria:

Kingdom of Bavaria:

- Knight of St. Hubert[6]

- Knight of the Military Merit Order, 1st Class, ca. 1866[7]

- Grand Prior of Upper Bavaria of the Royal Bavarian House Equestrian Order of St. George, 1874[6]

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of Max Joseph[8]

Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 17 September 1863[9]

Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 17 September 1863[9].svg.png.webp) Austria-Hungary:[10]

Austria-Hungary:[10]

- Knight of the Golden Fleece, 1868

- Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1893

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa, 1917

Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, 14 June 1869[11]

Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, 14 June 1869[11] Württemberg:

Württemberg:

- Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown, 1876[12]

- Grand Cross of the Military Merit Order[8]

.svg.png.webp) Spain: Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III, 19 December 1883[13]

Spain: Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III, 19 December 1883[13].svg.png.webp) Baden:[14]

Baden:[14]

- Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1887

- Knight of the Order of Berthold the First, 1887

.svg.png.webp) Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 1888[15]

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, 1888[15].svg.png.webp)

Sweden-Norway: Knight of the Seraphim, 12 July 1895[16]

Sweden-Norway: Knight of the Seraphim, 12 July 1895[16]_crowned.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Italy: Knight of the Annunciation, 6 September 1897[17]

Kingdom of Italy: Knight of the Annunciation, 6 September 1897[17].svg.png.webp) Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 1900 – wedding gift[18]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 1900 – wedding gift[18] Kingdom of Romania: Collar of the Order of Carol I, 1913[19]

Kingdom of Romania: Collar of the Order of Carol I, 1913[19] Denmark: Knight of the Elephant[20]

Denmark: Knight of the Elephant[20].svg.png.webp) Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion[20]

Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion[20].svg.png.webp) Ottoman Empire: Order of Imtyiaz[20]

Ottoman Empire: Order of Imtyiaz[20].svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Prussia:

Kingdom of Prussia:

- Knight of the Black Eagle[20]

- Pour le Mérite (military)[8]

Russian Empire: Knight of St. Andrew[20]

Russian Empire: Knight of St. Andrew[20].svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown[20]

Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Rue Crown[20]

Ancestry

References

- Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August 1914, and on France two days later.

- See, e.g., Toland, John (1976). Adolf Hitler. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0-385-03724-4. ("Toland") and Large, David C. (1997). Where Ghosts Walked: Munich's Road to the Third Reich. New York: Doubleday & Company. pp. 48–49. ISBN 0-393-03836-X. ("Large").

- Kershaw, Ian (1999). Adolf Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 89–90. ISBN 0-393-04671-0. ("Kershaw").

- Anifer Erklärung, 12./13. November 1918 Archived 2009-02-27 at the Wayback Machine (in German) Historisches Lexikon Bayerns, accessed: 10 May 2008

- Beisetzung Ludwigs III., München, 5. November 1921 (in German) Historisches Lexikon Bayerns – Funeral of Ludwig III, accessed: 1 July 2011

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Bayern (1908), "Königliche Orden", pp. 7, 11

- Bayern (1867). Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Königreichs Bayern: 1867. Landesamt. p. 95.

- "Ludwig III. (Wittelsbach) König von Bayern". the Prussian Machine. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Staatshandbuch für das Großherzogtum Hessen und bei Rhein (1879), "Großherzogliche Orden und Ehrenzeichen ", p. 11

- "Ritter-Orden", Hof- und Staatshandbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie (in German), 1918, pp. 50, 52, 55, retrieved 7 August 2020

- Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Großherzogtums Oldenburg0: 1879. Schulze. 1879. p. 33.

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Württemberg (1907), "Königliche Orden" p. 28

- "Real y distinguida orden de Carlos III", Guóa Oficial de España (in Spanish), 1887, p. 153, retrieved 4 March 2019

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1896), "Großherzogliche Orden" pp. 63, 77

- Staatshandbuch für das Großherzogtum Sachsen / Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1900), "Großherzogliche Hausorden" p. 16

- Sveriges Statskalender (in Swedish), 1905, p. 440, retrieved 20 February 2019 – via runeberg.org

- Italia : Ministero dell'interno (1900). Calendario generale del Regno d'Italia. Unione tipografico-editrice. p. 54.

- Albert I;Museum Dynasticum N° .21: 2009/ n° 2.

- "Ordinul Carol I" [Order of Carol I]. Familia Regală a României (in Romanian). Bucharest. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Justus Perthes, Almanach de Gotha (1921) p. 13

Sources

- Ludwig III. von Bayern, 1845–1921, Ein König auf der Suche nach seinem Volk, by Alfons Beckenbauer (Regensburg: Friedrich Pustet, 1987). The standard modern biography.

- Ludwig, Prinz von Bayern, Ein Lebens und Charakterbild, by Hans Reidelbach (München: Eduard Pohls, 1905). Particularly good for Ludwig's early life.

- Von der Umsturznacht bis zur Totenbahre: Die letzte Leidenszeit König Ludwigs III., by Arthur Achleitner (Dillingen: Veduka, 1922). A detailed work about the last three years of Ludwig's life.

- Ludwig III. König von Bayern: Skizzen aus seiner Lebensgeschichte, by Hubert Glaser (Prien: Verkerhrsverband Chiemsee, 1995). An illustrated catalogue of an exhibition held in Wildenwart in 1995.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Louis". |

Media related to Ludwig III of Bavaria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ludwig III of Bavaria at Wikimedia Commons- The King's photo

- Newspaper clippings about Ludwig III of Bavaria in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Ludwig III of Bavaria Born: 7 January 1845 Died: 18 October 1921 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Otto I |

King of Bavaria 5 November 1913 – 13 November 1918 |

Monarchy abolished |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Otto I as King of Bavaria |

Bavarian Head of State 5 November 1913 – 13 November 1918 |

Succeeded by Kurt Eisner as Prime Minister of Bavaria |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Himself | — TITULAR — King of Bavaria 13 November 1918 - 18 October 1921 Reason for succession failure: Kingdom abolished in 1918 |

Succeeded by Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria |

.jpg.webp)