Lumiton

Lumiton was a film production company founded in Argentina in 1932 at the start of the golden age of film in that country. Its lowbrow, populist films appealed to local audiences and were highly successful in Argentina and throughout Latin America. It was the main competitor to Argentina Sono Film in the 1940s. After World War II (1939–45) Lumiton faced increased government regulation, rising costs and loss of audiences to more sophisticated Hollywood productions. The company was forced to close in 1952.

| |

| Type | Company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Film studio |

| Fate | Bankrupt |

| Founded | Munro, Buenos Aires, Argentina (17 December 1932) |

| Defunct | May 15, 1952 |

| Headquarters | , Argentina |

Area served | Latin America |

Foundation

Lumiton was founded in the town of Munro, Buenos Aires, with an initial capital of 300,000 pesos.[1] The name "Lumiton" is made from the words for "light" and "sound". The full name was "Sociedad Anónima Radio Cinematográfica Lumiton" (Lumiton Radio Cinematography Company Ltd.)[2] The founders had earlier pioneered radio broadcast in Argentina, and were now pioneering sound films.[3] They had made one of the first radio broadcasts in the world in August 1920 from the Teatro Coliseo in Buenos Aires. They were César José Guerrico, Enrique T. Susini, Luis Romero Carranza and Miguel Mujica.[1] The first Lumiton studio was built with a modern laboratory and technical facilities on property owned by Isabel Zeller de Lehan.[1] A complete crew was hired in the United States.[1] This included the director of photography John Alton, and the sound designer Lazlo Kish.[4]

The state was not involved in the film industry, either directly or through subsidies.[4] Without the same bargaining power as the big Hollywood studios, the local studios could not demand a share of receipts from the distributors, but had to sell their films for a flat rate and therefore had to keep costs and capital expenditures to the minimum.[5] In the early years, Lumiton's audience was struggling with the effect of the Great Depression of the 1930, but the cheap and lighthearted productions perhaps helped people escape from their problems.[6]

There are distinct regional dialects in Latin America. Castilian Spanish is often not easy for local people to understand. Subtitling would not work with the audiences of the 1930s, many of whom were semi-literate. This created demand for locally produced sound films.[7] Lumiton employed local actors experienced in radio or popular theater.[4] Although locally made films were not as technically slick as those from Hollywood, films with local actors, themes and settings appealed to local audiences.[8] Lumiton became known for its lowbrow tango films.[9] Carlos Gardel (1890–1935) made tango popular throughout Latin America, and this created a large export market for Lumiton's films.[10]

Growth

Lumitron began operation on 17 December 1932, producing several test short films. The logo and opening sequence of each film featured a huge gong sounded by Michael Borowsky, the main dancer of the Teatro Colón.[1] Lumiton's first feature was Los tres berretines (The Three Hobbies, 1933) directed by Enrique T. Susini and starring the local actors Luis Sandrini and Luisa Vehil.[1][7] Alton was not credited but may have played and important role in direction and cinematography.[11][lower-alpha 1] Los tres berretines was released on 19 May 1933. The film cost 18,000 pesos and earned over one million.[1] The film depicted a family whose members were obsessed with the three national "berretines" (interests or hobbies) of tango, football and cinema. Sandrini's performance made him the first local cinema star.[2][lower-alpha 2]

In 1935 the director Manuel Romero joined the studio. He made one of Lumitron's great successes, the musical Noches de Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires Nights, 1935), with Tita Merello and Fernando Ochoa.[1] He also directed the musical El caballo del pueblo (The Favorite). His next film for Lumiton, La muchachada de a bordo (Boys on Board, 1936), was a major popular success.[14] Romero made populist genre films for Lumiton including the film noir Fuera de la ley (Outside the Law, 1938), the romantic comedy La rubia del camino (The Blonde on the Road, 1938) and Mujeres que trabajan (Women Who Work, 1938).[15] Mujeres que trabajan included Niní Marshall in her first film role. It was unusual in depicting women in the workplace, but otherwise was a conventional romantic melodrama. Marshall emerged as a strong and original comedian, and starred in a series of Lumiton films in the years that followed.[16]

Romero was the main film director for Lumiton until 1943, and directed over half the studio's films.[14] Formerly a tango lyricist and musical variety show director, he turned out cheerful and predictable comedies aimed at working class audiences. Romero always treated the working poor as a dignified community deserving respect. The critics looked down on his work, with its melodramatic plots and happy endings, but the films had great appeal to his audience.[17] These successful films, and those of other Argentine studios in the época de oro (golden age) spurred Hollywood to produce Spanish-language films for the Latin American market, but without much success.[15]

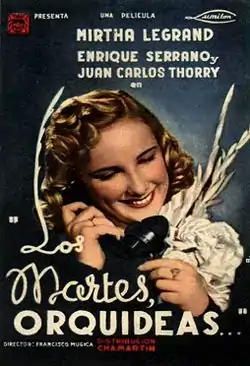

La chismosa (The Gossip, 1937), directed by Enrique Susini, was the first film made in Latin America to earn an honorable mention at a European film festival, in Venice. Margarita, Armando y su padre (1939), directed by Francisco Múgica, was also mentioned in Venice.[18] The Argentine Academy of Cinematography Arts and Sciences, founded in 1941, gave its first awards the next year. Lumiton won the prize for best picture with Los martes, orquídeas, a comedy. The writers, Sixto Pondal Ríos and Carlos A. Olivari, and the lead actress, Mirtha Legrand, were also recognized.[19] By 1942 the film industry in Argentina was the most technically advanced in South America. Lumiton and other majors such as Argentina Sono Film and Artistas Argentinos Asociados were at their peak.[20]

During World War II (1939–45) Argentina was careful not to upset the Axis powers, and banned or forced changes to some American films. Banned films included The Invaders (1941), Secret Agent of Japan (1942) and For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943).[21] In response the United States banned the export of unexposed film to Argentina, despite lack of evidence that the privately held studios were producing films or newsreels sympathetic to the Axis. Since supplies could not be obtained from Germany, the film industry suffered. Lumiton and Argentina Sono Film were the only studios with enough stock to last a year, and film makers had to rely on expensive black market supplies from Brazil or Chile.[22]

Last years

The focus by Lumiton and other Argentine studios on populist local themes was in contrast to the more sophisticated offerings from Hollywood, and appealed more to working-class people than to the elite. However, the studios avoided depicting real social issues and struggles.[23] For two decades Lumiton made films that were shown throughout Latin America with great success, but by the 1950s local cinema was losing audiences to foreign productions with more modern and relevant subjects.[1]

Raúl Apold, Juan Perón's undersecretary of culture, implemented an authoritarian regime of film censorship.[24] The industry was suffering from declining demand, rising costs and shortages of raw material. Apold added burdensome regulation.[25] By the early 1950s Lumiton was in severe financial difficulties.[26] The studio's last completed film was the feature Reportaje en el infierno, made by Román Viñoly Barreto in 1951–52, and only released in 1959. On 5 May 1952 Lucas Demare began shooting Un guapo del 900, but when it was in its second week of filming Lumiton filed for bankruptcy.[1]

A museum was built in 2004 to house memorabilia of the film company in the former studios in Munro, in the municipality of Vicente López. It holds cameras, sets, pictures and posters.[1]

Film production

Some of Lumiton's films included:[27]

- Los tres berretines (The Three Whims, 1933)

- El caballo del pueblo (1935)

- Noches de Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires Nights, 1935)

- La muchachada de a bordo (1936)

- La vuelta de Rocha (1937)

- Fuera de la ley (1937)

- The Boys Didn't Wear Hair Gel Before (1937)

- El cañonero de Giles (1937)

- Jettatore (1938)

- Mujeres que trabajan (1938)

- La chismosa (1938)

- La rubia del camino (1938)

- Tres anclados en París (Three Argentines in Paris, 1938)

- Muchachas que estudian (College Girls, 1939)

- Así es la vida (1939)

- Divorcio en Montevideo (Divorce in Montevideo, 1939)

- Margarita, Armando y su padre (1939)

- La modelo y la estrella (The Model and the Star, 1939)

- La vida es un tango (1939)

- El inglés de los güesos (1940)

- Isabelita (1940)

- Carnaval de antaño (1940)

- Medio millón por una mujer (1940)

- Casamiento en Buenos Aires (Marriage in Buenos Aires, 1940)

- Mi amor eres tú (You Are My Love, 1941)

- Persona honrada se necesita (Honest Person Needed, 1941)

- El tesoro de la isla Maciel (1941)

- Los martes, orquídeas (On Tuesdays, Orchids, 1941)

- Yo quiero ser bataclana (I Want to Be a Chorus Girl, 1941)

- Águila blanca (White Eagle, 1941)

- Un bebé de París (1941)

- El mejor papá del mundo (The Best Father in the World, 1941)

- La novia de primavera (Spring Bride, 1942)

- Historia de crímenes (Tale of Crimes, 1942)

- El viaje (1942)

- Ven mi corazón te llama (When My Heart Calls, 1942)

- Los chicos crecen (The Kids Grow Up, 1942)

- Una luz en la ventana (1942)

- Noche de bodas (1942)

- Adolescencia (1942)

- Safo, historia de una pasión (1943)

- La calle Corrientes (1943)

- El espejo (The Mirror, 1943)

- Dieciséis años (1943)

- El fabricante de estrellas (1943)

- La guerra la gano yo (I Win the War, 1943)

- La hija del ministro (Daughter of the Minister, 1943)

- Mi novia es un fantasma (1944)

- Las seis suegras de Barba Azul (Bluebeard's Six Mothers-in-Law, 1945)

- La señora de Pérez se divorcia (Mrs. Perez and Her Divorce, 1945)

- El canto del cisne (Swan Song, 1945)

- Adán y la serpiente (1946)

- El ángel desnudo (1946)

- La muerte camina en la lluvia (1948)

- Morir en su ley (1949)

- La trampa (1949)

- Yo no elegí mi vida (1949)

- Abuso de confianza (1950)

- ¿Vendrás a media noche? (1950)

- Valentina (1950)

- Filomena Marturano (1950)

- Cartas de amor (1951)

- Las furias (1960)

References

Notes

- John Alton remained in Argentina until 1940, directing camera work and lighting on more than twenty films, but mostly worked for the rival Argentina Sono Film.[12]

- Los tres berretines was based on a hit play of the same name, in which the circus performer and actor Luis Sandrini played Eusebio, a brother with a dream of becoming a famous tango composer. Lumiton expanded his role in the film version.[13]

Citations

- Martínez 2004.

- Creacion de Argentina Sono Film Y Lumiton, Cinematec.

- Alabarces 2002, p. 59.

- Falicov 2007, p. 12.

- Karush 2012, p. 74.

- Alabarces 2002, p. 56.

- Rist 2014, p. 4.

- Karush & Chamosa 2010, p. 39.

- Karush & Chamosa 2010, p. 41.

- Karush 2012, p. 83.

- Rist 2014, p. 20.

- Karush 2012, p. 76.

- Karush 2012, p. 117-118.

- Rist 2014, p. 495.

- Falicov 2007, p. 13.

- Karush 2012, p. 127.

- Karush 2012, p. 167.

- Waldman 1994, p. 180.

- ARCHIVO · Premios Anuales 1941 - 1953.

- Falicov 2007, p. 16.

- Falicov 2007, p. 19.

- Falicov 2007, p. 21.

- Karush & Chamosa 2010, p. 40.

- Mor 2012, p. 52.

- Mor 2012, p. 53.

- Mor 2012, p. 54.

- Lumiton, IMDb.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lumiton. |

Sources

- Alabarces, Pablo (2002). Fútbol y patria: el fútbol y las narrativas de la nación en la Argentina (in Spanish). Prometeo Libros Editorial. ISBN 978-950-9217-21-8. Retrieved 2014-06-02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "ARCHIVO · Premios Anuales 1941 - 1953" (in Spanish). Academia de Artes y Ciencias Cinematográficas. Archived from the original on 2014-05-31. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- "Creacion de Argentina Sono Film Y Lumiton". Historia del Cine Argentino. Cinematec. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- Falicov, Tamara Leah (2007). The Cinematic Tango: Contemporary Argentine Film. Wallflower Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-904764-92-2. Retrieved 2014-06-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karush, Matthew B.; Chamosa, Oscar (2010-04-30). The New Cultural History of Peronism: Power and Identity in Mid-Twentieth-Century Argentina. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-9286-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karush, Matthew B. (2012-05-15). Culture of Class: Radio and Cinema in the Making of a Divided Argentina, 1920–1946. Duke University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-8223-5264-8. Retrieved 2014-06-02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Lumiton [ar]". IMDb. Retrieved 2014-06-01.

- Martínez, Adolfo C. (1 August 2004). "Lumiton renace en un museo". La Nacion (in Spanish). Retrieved 2014-06-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mor, Jessica Stites (2012-05-01). Transition Cinema: Political Filmmaking and the Argentine Left Since 1968. University of Pittsburgh Pre. ISBN 978-0-8229-7797-1. Retrieved 2014-06-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rist, Peter H. (2014-05-08). Historical Dictionary of South American Cinema. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8108-8036-8. Retrieved 2014-06-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waldman, Harry (1994-01-01). Beyond Hollywood's Grasp: American Filmmakers Abroad, 1914–1945. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-2841-4. Retrieved 2014-06-02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)