Madeleine Lavigne

Madeleine Lavigne (born, Lyon, February 6, 1912 - died, Paris, February 24, 1945), code name Isabelle, was a member of the French Resistance and an agent of the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) organization during World War II. The purpose of SOE was to conduct espionage, sabotage, and reconnaissance in occupied Europe against the Axis powers, especially Nazi Germany. SOE agents allied themselves with resistance groups and supplied them with weapons and equipment parachuted in from England. Lavigne parachuted into the Saône-et-Loire Department of France near Taizé on May 23, 1944 and worked as a wireless operator and a courier for the Silversmith network (or circuit). She died of an embolism.

Madeleine Lavigne | |

|---|---|

| Born | 6 February 1912 Lyon, France |

| Died | 24 February 1945 (aged 33) Paris, France |

| Allegiance | France |

| Service/ | Special Operations Executive, French Resistance |

| Years of service | 1940-1944 |

| Rank | Field agent (courier) |

| Unit | SOE F Section, Network Silversmith |

Early life

Born Madeleine Rejeuny, the daughter of a fabric designer, she married Marcel Lavigne when she was 19 years old and had two children, Guy and Noel. Her husband became a prisoner of war early in World War II and after he was released by the Germans in 1943 they divorced. Her appearance was described by her SOE colleague, Robert Boiteux, as "unexceptional." She had "untapped intelligence" and was noted for "careful following of instructions."[1] She spoke little or no English.[2]

Lavigne worked in the town hall of Lyon and her first job with the French Resistance was producing false identity cards and other documents needed by SOE agents and allied airmen shot down over France and attempting to escape capture by the Germans. She allowed SOE agent Henri Borosh to keep his wireless set in her house.[3]

SOE network Silversmith

Lavigne began traveling as a courier for the SOE in 1943. In January 1944 Borosh and Lavigne realized that the French police were attempting to arrest them, and requested evacuation. Along with several other compromised SOE agents they were evacuated by a British military aircraft air from a field near Angers to England on February 4. After her departure, Lavigne was tried and convicted in absentia in Lyon as a terrorist and sentenced to life imprisonment.[4]

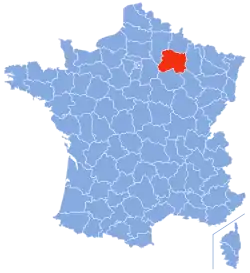

In England, Lavigne received para-military, parachute, and wireless training. Her training, however, was cut short due to a shortage of SOE agents in France. She returned to France as a half-trained wireless operator. She parachuted into France on May 23-24, 1944 and moved north to Reims to establish the Silversmith network there. She rented a house in Épernay to serve as a base. Her colleague Henri Borosh joined her as head of Silversmith. For the next several months she worked as a courier delivering messages and arranging with SOE in London for air drops of weapons and supplies to the French resistance. "The Germans were everywhere and [she] often had to pass through areas under fire, showing great courage and common sense."[5]

Lavigne had to hide from the Germans in a safehouse when the Silversmith network was compromised. The American army liberated Reims on August 29, 1944. She finished her mission with SOE in September. Her two sons had lived with her parents while she worked for SOE and she reunited with them in Paris. She was unable to return to her home in Lyon because the life sentence for terrorism had not been commuted by the court. She died in Paris of an embolism (blood clot) on February 25, 1945.[6]

Lavigne was described in official documents, possibly by Borosh, as "a most courageous and tactful woman, who rendered great service to the cause...She did her job unquestionably well...a great-hearted lady for whom I have much respect and liking."[7]

References

- O'Connor, Bernard (2018), SOE Heroines, Gloucestershire: Amberly Publishing, p. 310

- Escott, Beryl E. (2010), The Heroines of SOE, Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, p. 200

- Escott, p. 199

- Escott, p. 200

- O'Connor, pp. 311-313

- O'Connor, p. 313

- O'Connor, p. 313