Mahmudiyah rape and killings

The Mahmudiyah rape and killings were war crimes involving the gang-rape and murder of 14-year-old Iraqi girl Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi and the murder of her family by United States Army soldiers on March 12, 2006. It occurred in the family's house to the southwest of Yusufiyah, a village to the west of the town of Al-Mahmudiyah, Iraq. Other members of al-Janabi's family murdered by Americans included her 34-year-old mother Fakhriyah Taha Muhasen, 45-year-old father Qassim Hamza Raheem, and 6-year-old sister Hadeel Qassim Hamza Al-Janabi.[1] The two remaining survivors of the family, 9-year-old brother Ahmed and 11-year-old brother Mohammed, were at school during the massacre and orphaned by the event.

| Mahmoudiyah Rape and Killings | |

|---|---|

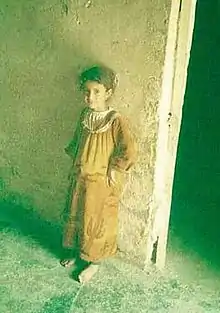

Abeer Qassim Hamza at the age of seven | |

| |

| Location | Yusufiyah, Baghdad Governorate, Iraq |

| Coordinates | 33.06°N 44.22°E |

| Date | March 12, 2006 |

| Target | Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi |

Attack type | war rape, mass murder |

| Deaths | 4 |

| Perpetrators | 5 United States Army soldiers from Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) |

Five U.S. Army soldiers of the 502nd Infantry Regiment were charged with rape and murder; Specialist Paul E. Cortez, Specialist James P. Barker, Private First Class Jesse V. Spielman, Private First Class Brian L. Howard, and Private First Class Steven D. Green[2]). Green was discharged from the U.S. Army for mental instability before the crimes were known by his command, whereas Cortez, Barker, Spielman and Howard were tried by U.S. Army General Courts Martial, convicted, and sentenced to prison.[2] Green was tried and convicted in a United States civilian court and was also sentenced to life in prison.[3]

Background

Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi (Arabic: عبير قاسم حمزة الجنابي ‘Abīr Qāssim Ḥamza al-Janābī; 19 August 1991 – 12 March 2006),[4][5] lived with her mother and father (Fakhriya Taha Muhasen, 34, and Qassim Hamza Raheem, 45, respectively) and her three siblings: 6-year-old sister Hadeel, 9-year-old brother Ahmed, and 11-year-old brother Mohammed. Of modest means, Abeer's family lived in a one-bedroom house that they did not own, with borrowed furniture, in the village of Yusufiyah, which lies west of the larger township of Al-Mahmudiyah, Iraq.[6] The family was very close. Her father, Qassim, worked as a guard at a date orchard. Abeer's mother, Fakhriya, was a stay-at-home mom. According to her brothers, little Hadeel, Abeer's 6-year-old sister, loved a sweet plant that grew in the yard, was playful but not very mischievous, and enjoyed playing hide and seek with them. Qassim doted on his family, hoping that he would one day be able to buy a home for them and that they would live and eat like everyone else. He also had a dream that his children would finish college. According to her neighbours, at the time of the massacre, Abeer spent most of her days at home, as her parents would not allow her to go to school because of security concerns. Having been born only months after the Gulf War, which devastated civilian infrastructure in Iraq, and living her entire life under sanctions, followed by the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq, Abeer had dreams as well, hoping to one day live "in the big city" (Baghdad). Her relatives describe her as proud.

Although she was only a 14-year-old child, Abeer endured repeated sexual harassment from U.S. soldiers. Abeer's home was situated approximately 200 meters (220 yards) from a six-man U.S. traffic checkpoint (TCP), southwest of the village.[7][8] From their checkpoint, the soldiers would often watch Abeer doing her chores and tending the garden. The neighbors had warned Abeer's father of this, but he replied it was not a problem as she was just a small girl.[8] Abeer's brother Mohammed (who along with his younger brother was at school at the time of the murders and thus survived) recalls that the soldiers often searched the house. On one such occasion, Private First Class Steven D. Green ran his index finger down Abeer's cheek, an action which had terrified her.[9] Abeer's mother told her relatives before the murders that, whenever she caught the soldiers staring at Abeer, they would give her the thumbs-up sign, point to her daughter and say, "Very good, very good." Evidently this had concerned her and she made plans for Abeer to spend nights sleeping at her uncle's (Ahmad Qassim's) house.[9][10] According to an affidavit later filed by the FBI, Green discussed raping the girl in the days preceding the event.

Rape and murders

On March 12, 2006, soldiers at the checkpoint (from the 502nd Infantry Regiment) – consisting of Green, Specialist Paul E. Cortez, Specialist James P. Barker, Private First Class Jesse V. Spielman, and Private First Class Brian L. Howard – had been playing cards, illegally drinking alcohol (whiskey mixed with an energy drink), hitting golf balls, and discussing plans to rape Abeer and "kill some Iraqis."[11] Green was very persistent about "killing some Iraqis" and kept bringing up the idea. At some point, the group decided to go to Abeer's home, after they had seen her passing by their checkpoint earlier. The four soldiers of the six-man unit responsible for the checkpoint – Barker, Cortez, Green, and Spielman – then left their posts for Abeer's home. Two men, Howard and another soldier, remained at the post. Howard had not been involved in discussions to rape and murder the family. He heard the four men talking about it and saw them leave, but thought they were joking and were planning to beat up some Iraqi men to blow off some steam. The sixth soldier at the checkpoint had no involvement.

On the day of the massacre, Abeer's father Qassim was enjoying time with his family, while his sons were at school.[12] In broad daylight, the five U.S. soldiers walked to the house, not wearing their uniforms, but wearing army-issue long underwear to look like "ninjas",[9] and separated 14 year-old Abeer and her family into two different rooms. Spielman was responsible for grabbing Abeer's 6 year-old sister, who was outside the house with her father, and bringing her inside the house.[13] Green then broke Abeer's mother's arms (likely evidence of a struggle that resulted when she heard her daughter being raped in the other room) and murdered her parents and younger sister, while two other soldiers, Cortez and Barker, raped Abeer.[14] Barker wrote that Cortez pushed Abeer to the floor, lifted her dress, and tore off her underwear while she struggled. According to Cortez, Abeer “kept squirming and trying to keep her legs closed and saying stuff in Arabic,” as he and Barker took turns holding her down and raping her.[15] Cortez testified that Abeer heard the gunshots in the room in which her parents and little sister were being held, causing her to scream and cry even more as she was being violently raped by the men. Green then emerged from the room saying, "I just killed them, all are dead".[16] Green, who later said the crime was "awesome",[17] then raped Abeer and shot her in the head several times. After the massacre, Barker poured petrol on Abeer and the soldiers set fire to the lower part of the girl's body, from her stomach down to her feet. Barker testified that the soldiers gave Spielman their bloodied clothes to burn and that he threw the AK-47 used to murder the family into a canal. They left to "celebrate" their crimes with a meal of chicken wings.[18] Meanwhile, the fire from Abeer's body eventually spread to the rest of the room, and the smoke alerted neighbors, who were among the first to discover the scene.[2] One recalled, "The poor girl, she was so beautiful. She lay there, one leg was stretched and the other bent and her dress was lifted up to her neck."[10] They ran to tell Abu Firas Janabi, Abeer's uncle, that the farmhouse was on fire and that dead bodies could be seen inside the burning building. Janabi and his wife rushed to the farmhouse and doused some of the flames to get inside. Upon witnessing the scene inside, Janabi went to a checkpoint guarded by Iraqi Army soldiers to report the crime. Abeer's 9- and 11-year-old younger brothers, Ahmed and Mohammed, returned from school that afternoon to find smoke billowing from the windows. After going to their uncle's home, they returned to the house only to be traumatized, finding their father shot in the head, mother shot in the chest, 6-year-old sister Hadeel shot in the face, and 14-year-old sister Abeer's remains burning.[6]

The Iraqi soldiers immediately went to examine the scene and thereafter went to an American checkpoint to report the incident. This checkpoint was different from the one manned by the perpetrators. After approximately an hour, some soldiers from the checkpoint went to the farmhouse. These soldiers were accompanied by at least one of the perpetrators.

Cover up

Green and the other soldiers who participated in the incident lied to the Iraqi soldiers who arrived on scene immediately after the incident, telling them that the massacre had been perpetrated by Sunni insurgents. These Iraqi soldiers conveyed this information to Abeer's uncle, who viewed the bodies. This lie prevented the event from being recognized as a crime or widely reported amidst the widespread violence occurring during the occupation of Iraq.[9][19]

Sergeant Anthony Yribe learned of the massacre and told Private First Class Justin Watt, a newly assigned soldier to Bravo Company, that Green was a murderer. Watt conducted a personal inquiry about this alarming act by a fellow soldier and coworker. He talked to other members of his platoon who revealed to him that the gang rape and murder had in fact occurred. Watt then reported what he believed to be true to another non-commissioned officer in his platoon, Sergeant John Diem. Watt trusted Diem; he told him that he knew a terrible crime had been committed and asked for his advice, knowing that if he reported the crime he would be considered a traitor to his unit and could possibly be killed by them. Diem told him to be cautious, but that he had a duty as an honorable soldier to report the crimes to the proper authorities. Unfortunately, they did not trust their chain of command to protect them if they reported a war crime. As a result, Watt asked to speak with a mental health counselor, thereby bypassing the chain of command to report the crimes.[2] On June 22, 2006, the rape and the murders came to light when Watt revealed them during a mental health counseling session and then to Army criminal investigators.[20]

Before Watt reported the crimes, Green had previously been honorably discharged from the Army on May 16, 2006, before the crime was recognized, with "antisocial personality disorder".[21] The FBI assumed jurisdiction for the crime committed by Green under the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act[22] and the U.S. Department of Justice charged him with the murders.[21]

Alleged 2006 retaliation

On July 10, the Mujahideen Shura Council (now a part of the Islamic State) released a graphic video showing the bodies of Pfcs. Tucker and Menchaca. This video was accompanied by a statement saying that the group carried out the killings as "revenge for our sister who was dishonored by a soldier of the same brigade."[23][24] The Washington Post reports that Charles Babineau and two other individuals from the same unit were captured and killed by militants a month after the rape.[25][26] Local Iraqi officials, and U.S. officials, denied the killing of the GIs was an act of retaliation, because the soldiers were killed days before the revelation leaked out that U.S. soldiers had committed the massacre in Mahmudiyah. At the time of Menchaca and Tucker's abduction on June 16, 2006, only the perpetrators of the rape and murder, and a few soldiers in their unit engaged in covering up the crime, knew that it had been committed by U.S. soldiers. The crime was revealed by Watt on June 22, and American responsibility only became "public knowledge" in Iraq on July 4, days after which the video by the Mujahideen Shura Council was released. Also, the abduction occurred on June 16, nine days after the targeted killing of the Shura Council's leader, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, on June 7.[27][28]

The video from the Mujahideen Shura Council claimed that upon learning of the massacre, the group "kept their anger to themselves and didn't spread the news, but were determined to avenge their sister's honor". Locals may have been able to deduce the guilt of the U.S. soldiers from the nearby checkpoint, after the Americans and their Iraqi cohort unit provided the explanation, "Sunni extremists did this." A portion of locals served as auxiliary support for both for Al Qaeda in Iraq and the 1920s Revolutionary Brigade. Auxiliary support comprised both material aid and performing a human intelligence support function. Relaying the accusation of the local MNC-I unit to the insurgents was a basic function of that support. The Sunni extremists were able to eliminate themselves as suspects and, having an already low opinion of the U.S. military, may have assumed the guilt of the 101st Airborne soldiers. A statement issued along with the video stated that, "God Almighty enabled them to capture two soldiers of the same brigade as this dirty crusader." Other militant groups also made various claims or statements announcing revenge campaigns after the killings were reported on July 4, when the U.S. investigation into the incident was announced.[29][30]

On July 4, Jaysh al-Mujahidin claimed responsibility for downing a U.S. Army AH-64 Apache "in retaliation for the child, Abir, whom U.S. soldiers raped in Al-Mahmudiyah, south of Baghdad."[31] On July 12, the Islamic Army in Iraq claimed responsibility for a suicide car bomb near the entrance to the Green Zone in Baghdad, in support of the "Abir operations" targeting the "evil den in the Green prison".[32]

Legal proceedings

Green was arrested as a civilian, and convicted by a civilian court, the U.S. District Court in Paducah, Kentucky.[33] The other four, all active-duty soldiers, were convicted through courts-martial.

Steven Dale Green

Green was arrested in North Carolina while traveling home from Arlington, Virginia, where he had attended the funeral of a soldier. On June 30, 2006, the FBI arrested Green, who was held without bond and transferred to Louisville, Kentucky. On July 3, federal prosecutors formally charged him with raping and murdering Abeer, and with murdering her parents and younger sister. On July 10, the U.S. Army charged four other active duty soldiers with the same crime. A sixth soldier, Yribe, was charged with failing to report the attack, but not with having participated in the massacre.

On July 6, 2006, Green entered a plea of not guilty through his public defenders. U.S. Magistrate Judge James Moyer set an arraignment date of August 8 in Paducah, Kentucky.[34]

On July 11, his lawyers requested a gag order. "This case has received prominent and often sensational coverage in virtually all print, electronic and internet news media in the world. … Clearly, the publicity and public passions surrounding this case present the clear and imminent danger to the fair administration of justice," said the motion.[35] Prosecutors had until July 25 to file their response to the request.[36] On August 31, a federal judge rejected the gag order. U.S. District Judge Thomas Russell said there is "no reason to believe" that Green's right to a fair trial would be in jeopardy. Furthermore, he added, "It is beyond question that the charges against Mr. Green are serious ones, and that some of the acts alleged in the complaint are considered unacceptable in our society."[37]

Opening arguments in Green's trial were heard on April 27, 2009.[38] The prosecution rested its case on May 4.[39] On May 7, 2009, Green was found guilty by the federal court in Kentucky of rape and multiple counts of murder.[3] While prosecutors sought the death penalty in this case, jurors failed to agree unanimously and the death sentence could not be imposed.[40] On September 4, Green was formally sentenced to life in prison with no possibility of parole.[41] That Green was spared the death penalty provoked outrage from the family's relatives, with Abeer's uncle describing the sentence as "a crime -- almost worse than the soldier's crime".[42] Green was held in the United States Penitentiary, Tucson, Arizona, and died on February 15, 2014, from complications following an attempt at suicide by hanging.[43]

Appeal

Green challenged his convictions, claiming that the Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act is unconstitutional and that he should face a military trial.[44] Green lost his appeal in August 2011.[45]

James P. Barker

On November 15, 2006, Specialist Barker pleaded guilty to rape and murder as part of a plea agreement requiring him to give evidence against the other soldiers to avoid the death penalty. He was sentenced to 90 years in prison and must serve 20 years before being considered for parole, following which he would be dishonorably discharged. Barker wept during closing statements, and accepted responsibility for the rape and murders, saying the violence he had encountered in Iraq left him "angry and mean" toward Iraqis.[46] Journalists reported "he smoked a cigarette outside as a bailiff watched over him. He grinned but said nothing as reporters passed by."[47] He is currently held in the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.[48]

Paul E. Cortez

On January 22, 2007, Cortez pleaded guilty in a court martial to rape, conspiracy to rape, and four counts of murder as part of a plea deal to avoid the death penalty, and was sentenced to 100 years in prison followed by a dishonorable discharge.[49] He wept as he apologized for the crimes, saying he could not explain why he took part.[50] He is currently held in the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.[48]

Jesse V. Spielman

On August 3, 2007, Spielman, 23, was sentenced by a court martial to 110 years in prison with the possibility of parole after ten years, followed by a dishonorable discharge. He was convicted of rape, conspiracy to commit rape, housebreaking with intent to rape and four counts of felony murder. He had earlier pleaded guilty to lesser charges of conspiracy toward obstruction of justice, arson, wrongfully touching a corpse, and drinking.[51] As of 2009 Spielman was held in the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.[48]

Bryan L. Howard

Howard was sentenced by a court martial under a plea agreement for obstruction of justice and being an accessory after the fact. The court found that his involvement included hearing the others discussing the crime and lying to protect them, but not commission of the actual rape or murders.[52][53] Howard served a 27-month sentence, after which he was dishonorably discharged.[48]

Anthony W. Yribe

Yribe was initially charged with obstructing the investigation, specifically, dereliction of duty and making a false statement. In exchange for his testimony against the other men, the government dropped the charges against him and he accepted an administrative discharge characterized as "other than honorable".[48][54][55]

Others

Justin Watt

Watt, the whistleblower, received a medical discharge and is now running a computer business. He says that he received death threats after coming forward;[48] however, starting in 2010, he was asked by the US Army Center for the Army Profession and Ethic (CAPE) at West Point, New York, to be interviewed and speak before Army Profession audiences about his decision to report the crimes in accordance with his moral obligation to uphold the Army Ethic. Watt and Sergeant Diem have both done so, including venues at which hundreds of senior Army leaders were present, for which their acts were given standing ovations.

Survivors

Muhammed and Ahmed Qassim Hamza al-Janabi, the surviving brothers of murder victim Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi, are being raised by an uncle,[2] according to testimony in the courts-martial of Cortez, Barker and Spielman.

In popular culture

- The 2007 war film Redacted is loosely based upon the events at Mahmudiyah.

- The incident and the ensuing investigations were described in the book Black Hearts by Jim Frederick, published in 2010.[56][57]

- The play "9 Circles" by Bill Cain follows Daniel Reeves through the aftermath of Mahmudiyah and was performed in 2011 at the Bootleg Theatre in Los Angeles.[58]

- The attacks are referenced in the 2017 episode “Fair Game”, of the television series Homeland.

- The incident was covered extensively in March 2018, in Case 78 of Casefile True Crime Podcast.[2] The podcast also released an interview with Watt on February 1, 2020.

- The initial reporting of the incident is discussed first hand by Watt in episodes "Justin Watt Part 1" and Justin Watt Part 2" of the podcast Hazard Ground

See also

- Incident on Hill 192

- Sexual assault in the U.S. military

- FOB Ramrod kill team

- Human rights in post-Saddam Hussein Iraq

- Hamdania incident

- Haditha massacre

- Basra prison incident

- John E. Hatley

- Kandahar massacre

- United States war crimes

References

- "Soldier: 'Death walk' drives troops 'nuts'". CNN.com. Aug 8, 2006. Archived from the original on 2012-10-18. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- "Case 78: The Janabi Family - Casefile: True Crime Podcast". casefilepodcast.com. 17 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-04-14. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "US ex-soldier guilty of Iraq rape". BBC News. 2009-05-07. Archived from the original on 2009-05-09. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- "Iraq girl in troops rape case just 14 - World". theage.com.au. 2006-07-11. Archived from the original on 2012-11-03. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- "U.S. military names soldiers charged in rape, murder probe". CNN.com. Jul 10, 2006. Archived from the original on 2012-11-06. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- "Killings Shattered Dreams of Rural Iraqi Family". Associated Press. May 23, 2009. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- "FindLaw: U.S. v. Steven D. Green - Murder and Rape Charges against Former U.S. Army 101st Airborne Division Soldier From Ft. Campbell, Kentucky". News.findlaw.com. 2006-06-30. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- Akeel Hussein; Colin Freeman (2006-07-09). "Two dead soldiers, eight more to go, vow avengers of Iraqi girl's rape". Telegraph. Archived from the original on July 18, 2006. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- Rawe, Julie (2006-07-09). "A Soldier's Shame". TIME. Archived from the original on 2013-08-23. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- Ewen MacAskill. "US soldier sentenced to 100 years for Iraq rape and murder". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2016-08-20. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

- Smith, Stephen (August 7, 2006). "Whiskey And Golf Before Rape-Murder?". CBS News. Archived from the original on 2014-03-27. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- Barrouquere, Brett (May 29, 2009). "Iraqi family's relatives confront killer". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ""Black Hearts" Case Study: The Yusufiyah Crimes, Iraq, March 12, 2006". CAPE Center for the Army Profession and Ethic. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Editors (July 14, 2006). "Revelations about the rape and murder of an Iraqi girl show how U.S. occupation breeds war crimes". Socialist Worker. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Hopkins, Andrea (February 20, 2007). "Tearful soldier tells court of Iraq rape-murder". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "FindLaw: U.S. v. Steven D. Green - Murder and Rape Charges against Former U.S. Army 101st Airborne Division Soldier From Ft. Campbell, Kentucky". News.findlaw.com. 2006-06-30. Archived from the original on 2012-05-03. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- "Ex-U.S. soldier found guilty in Iraqi rape, deaths". Reuters UK. May 8, 2009. Archived from the original on 2016-01-16. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- "Rape: American soldiers 'took turns'". The Age. August 9, 2006. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- Iraqi Television Treatment of Reported Rape, Killing of Iraqi Girl Iraqi television stations on July 5, 2006

- Zoroya, Gregg (September 13, 2006). "Whistle-blower in anguish". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2012-07-23. Retrieved 2017-09-04.

- Federal court to try ex-soldier on Iraq charges Archived March 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. July 6, 2006.

- "18 USC Chapter 212". Archived from the original on June 28, 2006.

- "Beheading Desecration Video of Dead U.S. Soldiers Released on Internet by al Qaeda". The Jawa Report. 10 July 2006. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Mujahidin Shura Council Links US Soldiers Killing to 'Rape' of Iraqi Girl Islamic Renewal Organization website via OpenSource.gov, July 11, 2006. (subscription required)

- Ellen Knickmeyer; Joshua Partlow (2006-07-10). "Capital Charges Filed In Rape-Slaying Case: U.S. Details Allegations Against GIs in Iraq". The Washington Post. p. A11. Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- Joshua Partlow; Saad Al-Izzi (2006-07-12). "From Baghdad Mosque, a Call to Arms". The Washington Post. p. A08. Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

The hand-held video shows two bodies -- one decapitated, the other face down on the ground as someone steps on his head. The video was posted on an insurgent Web site, accompanied by a statement from the Mujaheddin al-Shura Council, a collection of several insurgent groups including al-Qaeda in Iraq, asserting that the soldiers were killed in retaliation for the rape and murder of an Iraqi girl and the murders of three members of her family, allegedly by U.S. soldiers from the same unit in the nearby town of Mahmudiyah.

- "Iraq Terror Chief Killed In Airstrike". CBS News. June 8, 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- Burns, John F. (8 June 2006). "Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, Leader of Al Qaeda in Iraq, Is Killed in U.S. Airstrike". Archived from the original on 2016-12-07. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- Salah al-Din Brigades Vows Revenge for Al-Mahmudiyah 'Rape' Case Islamic Renewal Organization (IRO) website in Arabic via OpenSource.gov, July 10, 2006

- Al-Mujahidin Army Responds to Alleged Rape of Iraqi Girl by US Soldiers Baghdad al-Rashid forum in Arabic via OpenSource.gov, July 10, 2006

- Doha Al-Jazirah Satellite Channel Television in Arabic via OpenSource.gov 1412 GMT Jul 04, 06

- Islamic Army in Iraq: Green Zone Attack 'in Support of Abir, Gaza Operations' Al-Firdaws Jihadist Forums at www.alfirdaws.org/vb on July 12, 2006

- Detroit Free Press, page A18, May 8, 2009

- CNN. "Ex-soldier pleads not guilty to rape, murder: Former Army private accused of raping woman, killing family". Archived from the original on July 18, 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-06.

- "MOTION TO RESTRAIN PARTIES AND OTHER TRIAL PARTICIPANTS FROM MAKING EXTRAJUDICIAL STATEMENTS OF INFLAMMATORY OR PREJUDICIAL NATURE" (PDF). United States District Court for the Western District of Kentucky. 2006-07-11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-12. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- CNN.com (2006-07-11). "Gag requested in Iraq rape-murder case". Archived from the original on 2006-09-22. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- "Judge in Rape-Murder Case Denies Gag Order". Associated Press. 2006-09-01. Archived from the original on 2007-12-05. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- Barrouquere, Brett (2009-04-27). "Ex-soldier trial for rape, murder in Iraq opens". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Associated Press. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- "Prosecution rests in trial for Iraq crimes". Associated Press. 2009-05-04. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- "US soldier spared death penalty". BBC News. 2009-05-21. Archived from the original on 2009-05-22. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- "Life for US soldier's Iraq crimes". BBC News. 2009-09-04. Archived from the original on 2009-09-05. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- "Iraqi relatives decry life for U.S. rape soldier". Reuters. May 22, 2009. Archived from the original on 2016-01-16. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- Almasy, Steve. "Former soldier at center of murder of Iraqi family dies after suicide attempt" Archived 2014-02-19 at the Wayback Machine. CNN. February 18, 2014; retrieved February 19, 2014.

- "Ex-soldier appealing sentences in Iraq deaths". Wdtn.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- "AFP: Ex-US soldier loses appeal of Iraq rape, murders". 2011-08-16. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- "Iraq rape soldier given life sentence". London: Guardian Unlimited. 2006-11-17. Archived from the original on 2014-04-29. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- "Iraq rape soldier given life sentence". Associated Press/USA Today. 2006-11-16. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- "Where are they now?". Louisville Courier Journal. 2009-04-13. Archived from the original on 2013-01-02. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- "US soldier admits murdering girl". BBC News. 2007-02-22. Archived from the original on 2007-02-23. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- Hall, Tim (2007-02-25). "US soldier jailed for 100 years for rape". London: Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- Lenz, Ryan (2007-08-04). "110-Year Sentence in Iraq Rape-Killing". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- Horswell, Cindy (2007-03-22). "Huffman soldier sentenced in Iraq atrocities". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2017-08-28. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- "US prosecutors seek death penalty in Iraq murders". Reuters. 2007-07-03. Archived from the original on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- Von Zielbauer, Paul (2006-11-15). "Soldier to Plead Guilty in Iraq Rape and Killings". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2016-01-16. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- "Soldier testifies another soldier admitted to attack on family". International Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. July 31, 2007. Archived from the original on August 4, 2007.

- Jim Frederick "BLACK HEARTS - One Platoon’s Descent Into Madness in Iraq’s Triangle of Death", publ. Harmony Books (2010) ISBN 9780230752948

- Joshua Hammer. "Death Squad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- "Theater review: '9 Circles' at Bootleg Theater". latimes.com. Archived from the original on 2014-05-06. Retrieved 2014-02-20.

External links

- Video: The Rape & Murder Scene in Mahmudiya - Short BBC Documentary from August 7, 2006

- Images: The Mahmudiya Massacre Images - A Photo Series

- Resources: The Massacre of Mahmudiya: A full detail of the case with court documents

- "Killings shattered dreams of rural Iraqi family." Associated Press at NBC News. 2009.

- Rape: American soldiers 'took turns' The Age Aug 8, 2006

- Steven Green's Apology to Victims May 28, 2009

- "I came over here because I wanted to kill people." Andrew Tilghman The Washington Post Sunday July 30, 2006

- Lessons from Yusufiyah: From Black Hearts to Moral Education Combined Arms Center - Army.mil

- Abeer Qassim Hamza al-Janabi at Find a Grave

- Fakhriyah Taha Muhsin at Find a Grave

- Hadeel Qasim Hamza at Find a Grave

- Qasim Hamza Raheem at Find a Grave