Majel Barrett

Majel Barrett-Roddenberry (/ˈmeɪdʒəl/; born Majel Leigh Hudec;[2] February 23, 1932 – December 18, 2008) was an American actress and producer. She was best known for her roles as Nurse Christine Chapel in the original Star Trek series and Lwaxana Troi on Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, as well as for being the voice of most onboard computer interfaces throughout the series. She became the second wife of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry.

Majel Barrett | |

|---|---|

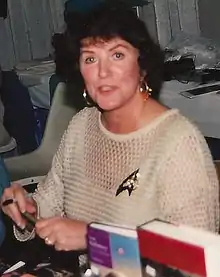

Majel Barrett at Gen Con in Indianapolis, Indiana in August 2006 | |

| Born | Majel Leigh Hudec February 23, 1932 |

| Died | December 18, 2008 (aged 76) Bel Air, California, U.S. |

| Other names | M. Leigh Hudec |

| Alma mater | University of Miami |

| Occupation | Actress, producer, voice actress |

| Years active | 1957–2008 |

Notable credit(s) | Christine Chapel, Lwaxana Troi, and voice of ship's computer in the Star Trek franchise |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Rod Roddenberry |

| Website | www |

| Signature | |

| |

As the wife of Roddenberry and given her ongoing relationship with Star Trek—participating in some way in every series during her lifetime—she was sometimes[2] referred to as "the First Lady of Star Trek".

Early life

Barrett was born in Cleveland, Ohio.[nb 1] She began taking acting classes as a child. She attended Shaker Heights High School, graduating in 1950[5][8] before going on to the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida, then had some stage roles and came to Hollywood. Her father, William Hudec, was a Cleveland police officer. He was killed in the line of duty on August 30, 1955[9] while Barrett was touring with an off-Broadway road company.

Career

Barrett was briefly seen in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957) in an ad parody at the beginning of the film, and had roles in a few movies, including Love in a Goldfish Bowl (1961), Sylvia (1965), A Guide for the Married Man (1967), and Track of Thunder (1967). She worked at the Desilu Studios on several TV shows, including Bonanza, The Untouchables, The Lucy Show, and The Lieutenant (produced by Gene Roddenberry). She received training in comedy from Lucille Ball. In 1960, she played Gwen Rutherford on Leave It to Beaver.

Star Trek

In various roles, Barrett participated in every incarnation of the popular science fiction Star Trek franchise produced during her lifetime, including live-action and animated versions, television and cinema, and all of the time periods in which the various series have been set.

She first appeared in Star Trek's initial pilot, "The Cage" (1964), as the USS Enterprise's unnamed first officer, "Number One". Barrett was romantically involved with Roddenberry, whose marriage was on the verge of failing at the time, and the idea of having an otherwise unknown woman in a leading role just because she was the producer's girlfriend is said to have infuriated NBC network executives who insisted that Roddenberry give the role to a man.[10] William Shatner corroborated this in Star Trek Memories, and added that female viewers at test screenings hated the character as well.[11] Shatner noted that female viewers felt she was "pushy" and "annoying" and also thought that "Number One shouldn't be trying so hard to fit in with the men."[12] Barrett often joked that Roddenberry, given the choice between keeping Mr. Spock (whom the network also hated) or the woman character, "kept the Vulcan and married the woman, 'cause he didn't think Leonard [Nimoy] would have it the other way around."[13]

When Roddenberry was casting for the second Star Trek pilot, "Where No Man Has Gone Before", she changed her last name from Hudec to Barrett and wore a blonde wig for the role of nurse Christine Chapel, a frequently recurring character,[2] who was introduced in "The Naked Time", the sixth new episode recorded, and was known for her unrequited affection for the dispassionate Spock. Her first appearance as Chapel in film dailies prompted NBC executive Jerry Stanley to yodel "Well, well—look who's back!".[10] In an early scene in Star Trek: The Motion Picture, viewers are informed that she has now become Doctor Chapel, a role which she reprised briefly in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, as Commander Chapel. Barrett provided several voices for Star Trek: The Animated Series, including those of Nurse Chapel and a communications officer named M'Ress, an ailuroid officer who served alongside Uhura.[14]

Barrett returned years later in Star Trek: The Next Generation, cast as the outrageously self-assertive, iconoclastic, Betazoid ambassador, Lwaxana Troi, who appeared as a recurring character in the series. Her character often vexed the captain of the Enterprise, Jean-Luc Picard, who spurned her amorous advances. She later appeared as Ambassador Troi in several episodes of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, where her character developed a strong relationship with Constable Odo.

She provided the regular voice of the onboard computers of Federation starships for Star Trek: The Original Series, Star Trek: The Next Generation, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Star Trek: Voyager, and most of the Star Trek movies. She reprised her role as a shipboard computer's voice in two episodes of the prequel series Star Trek: Enterprise, thus making her the only actor to have a role in all six televised Star Trek series produced up to that time. She also lent her voice to various computer games and software related to the franchise. The association of her voice with interactions with computers led to Google's Assistant project being initially codenamed Google Majel. Barrett had also made a point of attending a major Star Trek convention each year in an effort to inspire fans and keep the franchise alive.

On December 9, 2008, less than ten days before her death, Roddenberry Productions announced that she would be providing the voice of the ship's computer once again, this time for the 2009 motion picture reboot of Star Trek.[15] Sean Rossall, a Roddenberry family spokesman, stated that she had already completed the voiceover work, around December 4, 2008. The film is dedicated to Roddenberry and Barrett.

Other roles

My mother truly acknowledged and appreciated the fact that Star Trek fans played a vital role in keeping the Roddenberry dream alive for the past 42 years. It was her love for the fans, and their love in return, that kept her going for so long after my father passed away.

She appeared as Primus Dominic in Roddenberry's 1973 postapocalyptic TV drama pilot, Genesis II; as Dr. Bradley in his 1974 TV movie The Questor Tapes and as Lilith the housekeeper in his 1977 TV drama pilot, Spectre. She also appeared in Michael Crichton's 1973 sci-fi Western, Westworld as Miss Carrie, a robot brothel madam; the 1977 Stanley Kramer thriller The Domino Principle;[17] and the 1979 TV movie The Man in the Santa Claus Suit starring Fred Astaire. Her later film appearances included small roles in Teresa's Tattoo (1994) and Mommy (1995).

After Gene Roddenberry's death, Barrett took material from his archives to bring two of his ideas into production. She was executive producer of Earth: Final Conflict (in which she also played the character Dr. Julianne Belman), and Andromeda. She also served as creative director for Gene Roddenberry's Lost Universe, a comic book series based on another archival Roddenberry concept.[18]

In a gesture of goodwill between the creators of the Star Trek franchise and of Babylon 5 (some of whose fans viewed them as rivals),[19] she appeared in the Babylon 5 episode "Point of No Return", as Lady Morella, the psychic widow of the Centauri emperor, a role which foreshadowed major plot elements in the series.

Parodying her voice work as the computer for the Star Trek series, Barrett performed as a guest voice on Family Guy as the voice of Stewie Griffin's ship's computer in the episode "Emission Impossible".

Barrett's widely recognized voice performance as the Star Trek computer inspired the Amazon Alexa interactive virtual assistant, according to its developer Toni Reid, although Barrett had no direct role in it.[20]

Railroad voicework

The Southern Pacific Railroad used her voice talent contained inside Harmon Electronics (of Grain Valley, MO) track-side defect detector devices, used in various locations west of the Mississippi River. When a defect is identified on the passing train, the system responds with her recorded voice announcing the defect location information to the train crew over the radio. In railroad forums and railroad radio monitoring groups, she was and is still referred to as the "SP Lady". However, with the implementation of newer hotbox detector technology, finding her voice today on working detectors is very rare. The hotbox detectors that had her voice installed in them were not upgradeable to the newer digital signaling requirements, and finding parts for them was difficult. Today, her voice is found on smaller regional railroads, usually only at dragging equipment locations, such as in California at milepost 24.6 on the Metrolink Lancaster line (under the I-5 and I-210 interchange in Sylmar), and in Oregon on the Portland & Western at milepost 746.5, near Lake Oswego. These voiced detectors remain because the lines were once owned by Southern Pacific, and because only two unchanging recorded messages are used, compared to the dynamic changing library used in hotbox detectors. The only major railroad that still uses her voice today is Union Pacific.

Initially, Guilford commissioned Majel to say "Guilford Rail System", and the recording was programmed into detectors across the railroad. Train crews and local rail enthusiasts dubbed the MBTA Andover detector with the nickname "Andover Annie". Both the Andover and Shirley detectors with Majel's voice were replaced between 2015 and 2017 respectively with General Electric brand detectors, which use a male voice.

In 2006-2007, just before Majel Barrett-Roddenberry passed away on December 18th, 2008, the recently re-branded Pan Am Railways (formerly Guilford) was able to commission Majel one last time to say "Pan Am Railways" for their defect detectors. As of October 2020, Pan Am Railways still uses Majel Barrett-Roddenberry's voice for defect detectors at eight different locations between Maine, Massachusetts, and Upstate New York.

Pan Am Railways defect detectors that still utilize Barrett's voice recordings include the following locations: In District 1, MP 134.1 in Readfield, Maine, just off of Plains Road crossing. Second is MP 157.2 in Lewiston, Maine, just off of Merrill Road crossing. Lastly, MP 176.7 in Gray, Maine, just off of Depot Road crossing. In District 2, only one detector with her voice is in service. MP 234.2 in North Berwick, Maine, just off of Elm Street/Route 4 crossing. In District 3, there are four locations that still utilize her voice. First, MP 346.6 in Gardner, Massachusetts, near Parkers Street underpass. Second is at MP 369.1 in Wendell, Massachusetts, just off of Wendell Depot Road crossing. Third is at MP 410.9 in Zoar, Massachusetts, paralleling Zoar Road. Finally, at MP 440.2 in Hoosick, New York. The future of these defect detectors remains uncertain with the current state of Pan Am Railways being for sale. If a new railroad takes over, these rare defect detectors will likely be replaced.

Final voiceover work

Some of Barrett's final voiceover work was still in post-production, to be released in 2009 after her death, as mentioned in the credits of the 2009 movie Star Trek, again as the voice of the Enterprise computer. An animated production called Hamlet A.D.D. credited her as Majel Barrett Roddenberry, playing the voiceover role of Queen Robot.[21]

Personal life and death

In 1969, while scouting locations in Japan for MGM,[22] Roddenberry claimed that he realized that he missed Barrett and proposed to her by telephone.[23] In the version recited by Herbert F. Solow, Roddenberry traveled to Japan with the intention of marrying Barrett.[22] She subsequently joined Roddenberry in Tokyo, where they were married in a Shinto ceremony on August 6, 1969.[24] Roddenberry had considered it "sacrilegious" to use an American minister in Japan,[23] and the ceremony was attended by two Shinto priests as well as maids of honor. Roddenberry and Barrett both wore kimono, and spent their honeymoon touring Japan.[24] He continued to have liaisons with other women, telling his friends that while in Japan he had an encounter with a masseuse about a week after he was married.[25]

The new marriage was not legally binding, as his divorce from Eileen had not yet been finalized. This was resolved two days after his divorce was complete, and on December 29, a small ceremony was held at their home followed by a reception for family and friends. Despite this, the couple continued to celebrate August 6 as their wedding anniversary. His young daughter, Dawn, decided to live with him and Barrett,[26] and together they moved to a new house in Beverly Hills during the following October.[27] Roddenberry and Barrett had a son together, Eugene Jr., commonly referred to as Rod Roddenberry, in February 1974.[23] They remained married for the rest of Roddenberry's life, and Roddenberry died by Barrett's side on October 24, 1991, at a doctor's office in Santa Monica, California.[28]

After Gene Roddenberry died in 1991, Majel Barrett-Roddenberry commissioned Celestis to launch her together with Gene on an infinite mission to deepest space.[29] After manifesting them on NASA's "Sunjammer" mission, the agency cancelled the mission in 2014.[30] Celestis has rescheduled their launch for 2020, the next available commercial mission to deep space. A sample of the couple's cremated remains will be sealed into a specially made capsule designed to withstand space travel. A spacecraft will carry the capsule, along with digitized tributes from fans, on Celestis' "Enterprise Flight."[31]

Barrett-Roddenberry died on the morning of December 18, 2008, at her home in Bel Air, Los Angeles, California, as a result of leukemia. She was 76 years old.[32] A public funeral was held on January 4, 2009, in Los Angeles. More than 250 people attended, including Nichelle Nichols, George Takei, Walter Koenig, Marina Sirtis, Brent Spiner, Wil Wheaton, and many Trekkies.[33]

Honors

Barrett and her husband were honored in 2002 by the Space Foundation with the Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award[34] for their work creating awareness of and enthusiasm for space.

Filmography

- Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957) – shampoo demonstrator (uncredited)

- As Young as We Are (1958) – Joyce Goodwin

- The Black Orchid (1958) – Luisa (uncredited)

- The Buccaneer (1958) – Townswoman #1

- Love in a Goldfish Bowl (1961) – Alice

- Back Street (1961) – Woman at Table (uncredited)

- Bonanza (1962-1966, TV Series) – Annie Slocum / Belle Ganther

- The Quick and the Dead (1963) – Teresa

- Sylvia (1965) – Anne (uncredited)

- Made in Paris (1966) – Mrs. David Prentiss (uncredited)

- Country Boy (1966) – Miss Wynn

- A Guide for the Married Man (1967) – Mrs. Fred V.

- Track of Thunder (1967) – Georgia Clark

- Here Come the Brides (1968) - Tessa

- Westworld (1973) – Miss Carrie

- The Questor Tapes (1974, TV Movie) – Dr. Bradley

- The Domino Principle (1977) – Yuloff

- Spectre (1977, TV Movie) – Mrs. Schnaible

- The Suicide's Wife (1979, TV Movie) – Clarissa Harmon

- Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) – Dr. Chapel

- The Man in the Santa Claus Suit (1979, TV Movie) – Miss Forsythe

- Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) – Commander Chapel

- Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1993) – Lwaxana Troi

- Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-1999) – Ambassador Lwaxana Troi

- Teresa's Tattoo (1994) – Henrietta

- Star Trek Generations (1994) – Computer (voice)

- Star Trek: Voyager (1995-2001) – Computer (voice)

- Mommy (1995) – Mrs. Withers

- Star Trek: First Contact (1996) – Computer (voice)

- Star Trek: Nemesis (2002) – Computer (voice)

- Star Trek (2009) – Starfleet Computer (voice) (posthumous release)

- Hamlet A.D.D. (2014) – Queen Robot (voice) (final film role)

References

Notes

Citations

- "Majel Roddenberry, 'Star Trek' Actress, Dies at 76". The New York Times. December 19, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Majel Barrett Roddenberry: Actress who found fame as the 'First Lady of Star Trek', The Daily Telegraph, December 21, 2008

- "Corporate Bios". Roddenberry Entertainment. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Barrett". CBS Studios. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Shaker Heights High School grad Majel Roddenberry, 'First Lady of Star Trek,' dies". Cleveland Plain Dealer. December 19, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Majel B. Roddenberry, wife of 'Star Trek' creator, dies". Los Angeles Times. December 19, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "Remembering Majel Barrett-Roddenberry". CBS Studios. February 23, 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- "1950 Shaker Heights High School Yearbook". classmates.com.(registration required)

- ODMP: William Hudec. Viewed 2014-12-06.

- Solow, Herbert F.; Justman, Robert H. (1996). Inside Star Trek: The Real Story. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-89628-8.

- Star Trek Memories, dictated by William Shatner and transcribed by Chris Kreski, which HarperCollins published, with the ISBN 0-06-017734-9, in 1993, made this claim in the chapter on "The Cage".

- William Shatner, Star Trek Memories, Harper Collins, 1993. p.65

- "Bio and interview of Majel Barrett". Creation presents Majel Barrett. August 25–26, 1990. Archived from the original on January 17, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- Mangels, Andy (Summer 2018). "Star Trek: The Animated Series". RetroFan. TwoMorrows Publishing (1): 25–37.

- Roddenberry Productions press release, December 11, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2008. Archived December 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/7791210.stm

- Majel Roddenberry. "Majel Barrett Roddenberry – Biography". Roddenberry.com. Archived from the original on 2011-11-06. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- "Tekno-Comix Debuts First Titles". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Ziff Davis (63): 232. October 1994.

- Ntua.gr Archived 2009-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Green, Penelope (2017-07-11). "Alexa, Where Have You Been All My Life?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

When Toni Reid and her colleagues at Amazon set out to build the device that is now known as Alexa, they were inspired by the computer that drove the Enterprise on Star Trek (voiced by Majel Barrett Roddenberry, who played Nurse Chapel on the series and was married to the show’s creator). Focusing on cadence and an accent that would suggest 'smart, humble, helpful,' the team tested voices that a diverse population would respond to. 'Our goal was to have Alexa be humanlike,' Ms. Reid said, but why end there?

- "Voyages of Star Trek Computer Voice Majel Barrett Roddenberry". Voices.com. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Engel (1994): p. 139

- Van Hise (1992): p. 53

- Alexander (1995): p. 370

- Engel (1994): p. 140

- Alexander (1995): p. 372

- Alexander (1995): p. 377

- Alexander (1995): p. 7

- "Ashes of "Star Trek" creator and wife rocketing to deep space". Space Daily. January 26, 2009. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- "Solar Sail Demonstrator ('Sunjammer')". NASA.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- "Star Trek Community". Celestis.com. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- Sci-fi icon Majel Barrett Roddenberry dies at 76, Reuters, Thursday, December 18, 2008

- "L.A. funeral held for actress Majel Roddenberry". CTV News. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- – Space Foundation Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award Archived 2011-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- Alexander, David (1995). Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry. New York: Roc. ISBN 0-451-45440-5.

- Engel, Joel (1994). Gene Roddenberry: The Myth and the Man Behind Star Trek. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-6004-9.

- Solow, Herbert F.; Justman, Robert H. (1996). Inside Star Trek: The Real Story. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-89628-7.

- Van Hise, James (1992). The Man Who Created Star Trek: Gene Roddenberry. Pioneer Books. ISBN 1-55698-318-2.