Mamah Borthwick

Mamah Bouton Borthwick [1](June 19, 1869 – August 15, 1914) was a translator primarily noted for her relationship with Frank Lloyd Wright, which ended when she was murdered.[2] She and Wright were instrumental in bringing the ideas and writings of Swedish feminist Ellen Key to American audiences. Wright built his famous settlement called Taliesin in Wisconsin for her, in part, to shield her from aggressive reporters and the negative public sentiment surrounding their non-married status. Both had left their spouses and children in order to live together and were the subject of relentless public censure.

Mamah Borthwick | |

|---|---|

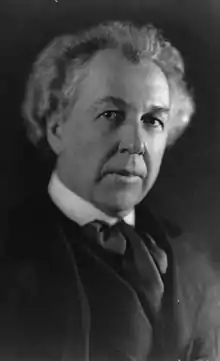

Borthwick in a newspaper in December 1911. | |

| Born | Mary Bouton Borthwick June 19, 1869 Boone, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | August 15, 1914 (aged 45) Spring Green, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Other names | Mamah Borthwick |

| Spouse(s) | Edwin Cheney |

| Partner(s) | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Children | 2 |

Early life and education

She was born as Mary Bouton Borthwick in Boone, Iowa to Marcus Smith Borthwick (1828-1900) (son of Alexander Borthwick and Vilitta Lamoreaux) and Almira A. Borthwick (née Bowcock) (1839-1898).[3][4] She had two sisters: Jessie Octavia Borthwick Pitkin (1864-1901) and Elizabeth Vilitta Borthwick (1866-1946). Borthwick earned her BA and MA at the University of Michigan in 1892 and 1893.[5] She later worked as a librarian in Port Huron, Michigan.

Marriage and family

In 1899, Borthwick married Edwin Cheney, an electrical engineer from Oak Park, Illinois, United States. They had two children: John (1902) and Martha (1905).[6]

Relationship with Wright

Mamah met Wright's wife, Catherine, through a social club. Soon after, Edwin commissioned Wright to design them a home, now known as the Edwin H. Cheney House. Mamah's sister, Elizabeth Vilitta Borthwick, lived in an apartment on the lower level of the house.

In 1909, Mamah and Wright left their spouses and traveled to Europe.[7] Most of their friends and acquaintances considered their open closeness to be scandalous, especially since Catherine had refused to agree to a divorce. Chicago newspapers criticized Wright, implying that he would soon be arrested for immorality, despite statements from the local sheriff that he could not prove that the couple was doing anything wrong. After the couple moved to Taliesin, the editor of the Spring Green, Wisconsin, newspaper condemned Wright for bringing scandal to the village. The press, which reported the European trip as a "spiritual hegira", called Mamah and Wright "soul mates" and also referred to Taliesin as the "love castle" or "love bungalow".[8][9] The scandal affected Wright's career for several years; he did not receive his next major commission, the Imperial Hotel, until 1916.

In 1911, Borthwick began translating the works of the Swedish feminist thinker and writer Ellen Key, whom she admired and had visited while in Europe.

Murder

On August 15, 1914, Julian Carlton, a male servant from Barbados who had been hired several months earlier and was apparently mentally unstable, set fire to the living quarters of Taliesin and murdered seven people with an axe as they fled the burning structure.[10][8] The dead included Mamah; her two visiting children, John and Martha; David Lindblom, a gardener; a draftsman named Emil Brodelle; Thomas Bunker, a workman; and Ernest Weston, the son of Wright's carpenter William Weston, who himself was injured but survived.[8][11] Thomas Fritz also survived the mayhem, and Weston helped to put out the fire that almost completely consumed the residential wing of the house.[12] In hiding, Carlton swallowed muriatic acid immediately following the attack in an attempt to kill himself.[10] When found, he was nearly lynched on the spot, but was taken to the Dodgeville jail.[10] Carlton died from starvation seven weeks after the attack, despite medical attention.[10] At the time, Wright was overseeing work on Midway Gardens in Chicago.[13]

In popular culture

A detailed nonfiction account of the tragedy at Taliesin is provided in Death in a Prairie House: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Murders by William R. Drennan.[14]

Mamah's time with Frank Lloyd Wright is the basis of Loving Frank, a novel by Nancy Horan.[15] Mamah is also a subject of T.C. Boyle's 2009 twelfth novel, The Women.[16]

An opera, Shining Brow, covers the story of the Cheneys and the Wrights, from when they meet in Wright's office, through the aftermath of Mamah's death. Music was composed by American composer Daron Hagen with a libretto by Paul Muldoon.

The death of Mamah Borthwick is described in the book The Rise of Endymion by Dan Simmons in a back-story of the persona of Frank Lloyd Wright.

The story of her death was recounted by Lorelai Gilmore in an episode of Gilmore Girls, "Let the Games Begin".

There is a song titled "Mamah Borthwick (A Sketch)" on the 2016 album "Ruminations" by Conor Oberst.

Notes

- "How Mamah Bouton Borthwick Became Martha and Other Errors". Fugitives Together. 2019-06-19. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- "The Terrible Crime at Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin". 2017-12-05. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- "Marcus Smith Borthwick (1828-1900) - Find A Grave..." www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- "Almira A. Bowcock Borthwick (1839-1898) - Find A..." www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- Calendar of the University of Michigan for 1892-93. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. 1893. p. 189.

- "Frank Lloyd Wright". www.steinerag.com. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- "The queer view of marital life". Fort Wayne Sentinel. 26 February 1912. p. 12. Retrieved 12 December 2016 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- "Six are slain in love castle". Racine Journal News. 17 August 1914. p. 10. Retrieved 12 December 2016 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- "Soulmate stunt loses its zest". Kokomo Daily Tribune. 3 August 1910. p. 1. Retrieved 12 December 2016 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- BBC News article: "Mystery of the murders at Taliesin".

- "Carleton is held on murder charges". Racine Journal News. 28 August 1914. p. 4. Retrieved 12 December 2016 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- "Mystery of the murders at Taliesin". 2001. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- "The Massacre at Frank Lloyd Wright's "Love Cottage"". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- William R. Drennan (18 January 2007). Death in a Prairie House: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Murders. Terrace Books. ISBN 978-0-299-22210-9.

- "Novel Sheds Light on Frank Lloyd Wright's Mistress". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- "T.C. Boyle's 'Women' Recasts Frank Lloyd Wright Bio". NPR.org. 3 March 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2014.