Mammon (painting)

Mammon, originally exhibited as Mammon. Dedicated to his Worshippers, is an 1885 oil painting by English artist George Frederic Watts, currently in Tate Britain. One of a number of paintings by Watts in this period on the theme of the corrupting influence of wealth, Mammon shows a scene from Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene in which Mammon, the embodiment of greed, crushes the weak through his indifference to their plight. This reflected Watts's belief that wealth was taking the place of religion in modern society, and that this worship of riches was leading to social deterioration. The painting was one of a group of works Watts donated to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) in late 1886, and in 1897 it was one of 17 Watts paintings transferred to the newly created Tate Gallery. Although rarely exhibited outside the Tate Gallery, the popularity of reproductions made Mammon one of Watts's better known paintings.

| Mammon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | George Frederic Watts |

| Year | 1885 |

| Type | Oil |

| Dimensions | 182.9 cm × 106 cm (72.0 in × 42 in) |

| Location | Tate Britain |

Background

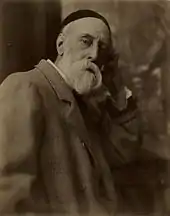

George Frederic Watts was born in 1817, the son of a London musical instrument manufacturer.[1] His two brothers died in 1823, and his mother in 1826, giving Watts an obsession with death throughout his life.[1] Meanwhile, his father's strict evangelical Christianity led to Watts developing a deep knowledge of the Bible but a strong dislike of organised religion.[1] Watts was apprenticed as a sculptor at the age of 10, and at the age of 16 was proficient enough as an artist to be earning a living as a portrait painter and as a cricket illustrator.[2][3] At the age of 18 he gained admission to the Royal Academy schools, although he disliked their methods and his attendance was intermittent.[2] In 1837 Watts was commissioned by Greek shipping magnate Alexander Constantine Ionides to copy a portrait of his father by renowned artist Samuel Lane; Ionides preferred Watts's version to the original and immediately commissioned two more paintings from him, allowing Watts to devote himself full-time to painting.[4]

In 1843 Watts travelled to Italy, where he remained for four years.[5] On his return to London he suffered from depression, and painted a number of notably gloomy works. His skills were widely celebrated, and in 1856 he decided to devote himself to portrait painting.[6] His portraits were extremely highly regarded.[6] In 1867 he was elected a Royal Academician, at the time the highest honour available to an artist,[5][upper-alpha 1] although he rapidly became disillusioned with the culture of the Royal Academy.[9] From 1870 onwards he became widely renowned as a painter of allegorical and mythical subjects;[5] by this time, he was one of the most highly regarded artists in the world.[10] In 1881 he added a glass-roofed gallery to his home at Little Holland House, which was open to the public at weekends, further increasing his fame.[11] In 1884 a selection of 50 of his works were shown at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, believed to have been the first such exhibition by any artist.[11]

Subject

Mammon originally meant wealth in Aramaic, but from the early days of the Christian Church the name was occasionally used to represent the personification of greed.[12] This notion of Mammon as an individual, rather than an abstract concept, became commonplace in English culture owing to Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene, published in the late 16th century, and later in John Milton's Paradise Lost (1667), both of which treated Mammon as an individual exemplar of greed.[12] As was the case with almost all English artists of the period, Watts was heavily influenced by the works of both Spenser and Milton.[12]

Watts based Mammon on a scene from Book II of The Faerie Queene in which the protagonist Guyon encounters Mammon in a cave containing "richesse such exceeding store as eie of man did never see before".[12][13] Mammon was one of a series Watts painted at around this time on the theme of the corruption brought about by wealth, including The Wife of Plutus (1880s), Sic Transit (1880–1882) and For he had Great Possessions (1894).[14]

Composition

Watts depicted Mammon as a corrupted version of traditional images of the gods.[15] This reflected his belief that the worship of wealth was taking the place of traditional beliefs in modern society, and that this attitude, which he described as "the hypocritical veiling of the daily sacrifice made to this deity",[15] was leading to social decay.[12] (His widow, Mary Seton Watts, wrote in 1912 that Watts had said that "Mammon sits supreme, while great art, as a child of the nation, cannot find a place; the seat is not wide enough for both".[12]) Mammon wears gold and scarlet robes, and crushes "whatever is weak and gentle and timid and lovely".[15][upper-alpha 2] Watts aimed to show Mammon not as crushing the weak through deliberate cruelty, but through an indifference to the damage he was causing.[15] His headdress resembles donkey's ears, an allusion to Thomas Carlyle's description of "serious, most earnest Mammonism grown Midas-eared" in Past and Present.[15]

Reception and legacy

Mammon was first exhibited in 1885, under the title of Mammon. Dedicated to his Worshippers.[15] The catalogue accompanying this exhibition described this unusual title as "righteously scornful".[15] Aside from an oil sketch now in the Watts Gallery,[15] only one completed version of Mammon was made.[15] This was among a number of paintings donated by Watts to the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) in late 1886.[16] In 1897 it was one of the 17 Watts works transferred to the newly created Tate Gallery (commonly known as the Tate Gallery, now Tate Britain);[17] at the time, Watts was so highly regarded that an entire room of the new museum was dedicated to his works.[18][19]

.jpg.webp)

Although rarely exhibited outside the Tate Gallery, cheap photographic reproductions of Mammon made by Frederick Hollyer circulated widely, making it one of Watts's better-known paintings.[15] In 1887 it was one of the paintings discussed by Scottish theologian P. T. Forsyth in his series of lectures on "Religion in Recent Art". Forsyth considered Mammon a companion to Watts's 1885 Hope, arguing that both depicted false gods and the perils awaiting those who attempted to follow them in the absence of faith.[20] By 1904 the image was well-enough known that the Daily Express reproduced the head of Mammon alongside that of John D. Rockefeller, a person of whom the newspaper greatly disapproved,[upper-alpha 3] implicitly inviting readers to draw comparisons.[15]

Watts returned to the theme of greed in Progress (1902–1904), one of his final works. This shows the figure of Mammon as one of three figures representing what Watts called "non-progress"; academia, wealth and laziness, oblivious to the emergence of Progress on horseback behind them.[21] The central figure was described by Watts as "money grubbing";[12] as with Mammon and many of his other works, Watts aimed to show spiritual and material values as inherently contradictory.[21]

Notes

- In Watts's time, honours such as knighthoods were only bestowed on presidents of major institutions, not on even the most well respected artists.[7] In 1885 serious consideration was given to raising Watts to the peerage; had this happened, he would have been the first artist so honoured.[8] In the same year, he refused the offer of a baronetcy.[5]

- From the description accompanying the painting on its initial exhibition.[15]

- The accompanying article described Rockefeller as "the greatest money tyrant the world has ever known".[15]

References

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 20.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 22.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 21.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 23.

- Warner 1996, p. 238.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 33.

- Robinson 2007, p. 135.

- Tromans 2011, p. 69.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 40.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. xi.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 42.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 230.

- The Faerie Queene, Edmund Spenser, Book II, Verse 32

- Smith 2001, p. 141.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 232.

- Tromans 2011, p. 22.

- Bills 2011, p. 9.

- Bills 2011, p. 5.

- Bills 2011, p. 44.

- Tromans 2011, p. 34.

- Bills & Bryant 2008, p. 272.

Bibliography

- Bills, Mark (2011). Painting for the Nation: G. F. Watts at the Tate. Compton, Surrey: Watts Gallery. ISBN 978-0-9561022-5-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bills, Mark; Bryant, Barbara (2008). G. F. Watts: Victorian Visionary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15294-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Leonard (2007). William Etty: The Life and Art. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2531-0. OCLC 751047871.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Alison (2001). Exposed: The Victorian Nude. London: Tate Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85437-372-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tromans, Nicholas (2011). Hope: The Life and Times of a Victorian Icon. Compton, Surrey: Watts Gallery. ISBN 978-0-9561022-7-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warner, Malcolm (1996). The Victorians: British Painting 1837–1901. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-8109-6342-9. OCLC 59600277.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)