Marcion hypothesis

The Marcion hypothesis or Marcionite priority (or priority of the Marcionite Gospel) is a possible solution to the synoptic problem. This hypothesis claims that the first produced or compiled gospel was that of Marcion and that this gospel of Marcion was used as inspiration either for some of the canonical gospels, or for all the canonical gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). The major supporter of this hypothesis is at present Matthias Klinghardt.

Gospel of Marcion

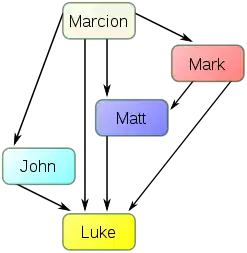

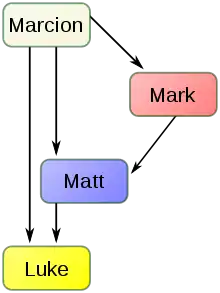

Marcion of Sinope is regarded by many scholars as having produced the first New Testament canon.[1][2] The order of the composition of the Synoptic Gospels according to the Marcion hypothesis is as follows:

- Marcion was the first author of a Gospel, which was simply called The Gospel (in Greek: Euangelikon) or The Gospel of the Lord.[3] His full canon also included the Apostolikon, which was an edited version of the Pauline Epistles without the Pastoral Epistles.[4]

- The Gospel of Matthew was written as a response to Marcion's Gospel, because the Christology of Marcion saw Jesus as different entity than the Messiah of the Jews, and he completely rejected the Old Testament, though took its account of creation and history as literal.

- The Gospel of Luke adapted the text of Marcion's Gospel but expanded it to conform to the Christology of Proto-orthodox Christianity, and also combined it with the parables either found in the Q document according to the two-source hypothesis, or directly from Matthew according to the Griesbach (two-gospel) hypothesis.

- The Gospel of Mark was composed of those parts of the Gospel that Luke and Matthew shared in common (the two-Gospel hypothesis), and therefore was a truncated Gospel of Marcion. Marcion himself claimed that his Gospel was the true original and that other Gospels had plagiarized his text.

Gospel of Marcion as an earlier version of Luke

Biblical scholars as varied as Johann Salomo Semler, Johann Gottfried Eichhorn, Albert Schwegler, Albrecht Ritschl, John Knox,[5]:6[6] Paul-Louis Couchoud, John Townsend, Matthias Klinghardt,[6] Joseph B. Tyson,[7] and David Trobisch[8] have dissented from the traditional view that the Gospel of Marcion was a revision of the Gospel of Luke (this traditional view may be called the "patristic hypothesis"). They argue that the Gospel of Luke is either a later redaction of the Gospel of Marcion ("Schwegler hypothesis"), or that both gospels are redactions of some prior gospel –a "proto-Luke" – with Marcion's text being closer to the original ("Semler hypothesis").[6] Several arguments have been put forward in favor of those two latter view.

Firstly, there are many passages found in Marcion's gospel that seem to contradict his own theology, which is unexpected if Marcion was simply removing passages from Luke that he didn't agree with. Matthias Klinghardt has argued:

The main argument against the traditional view of Luke’s priority to [Marcion] relies on the lack of consequence of his redaction: Marcion presumably had theological reasons for the alterations in "his" gospel which implies that he pursued an editorial concept. This, however, cannot be detected. On the contrary, all the major ancient sources give an account of Marcion’s text, because they specifically intend to refute him on the ground of his own gospel. Therefore, Tertullian concludes his treatment of [Marcion]: "I am sorry for you, Marcion: your labour has been in vain. Even in your gospel Christ Jesus is mine" (4.43.9).[5]:7 (emphasis in original)

Secondly, Marcion himself claimed that the gospel he used was original, whereas the canonical Luke was a falsification.[5]:8 The accusations of alteration are therefore mutual:

Tertullian, Epiphanius, and other ancient witnesses, all of whom knew and accepted the same Gospel of Luke we know, felt not the slightest doubt that the "heretic" had shortened and "mutilated" the canonical Gospel; and on the other hand, there is every indication that the Marcionites denied this charge and accused the more conservative churches of having falsified and corrupted the true Gospel which they alone possessed in its purity. These claims are precisely what we would have expected from the two rival camps, and neither set of them deserves much consideration.[9]:78

Thirdly, John Knox and Joseph Tyson have shown that, of the material that is omitted from Marcion's gospel but included in canonical Luke, the vast majority (79.5-87.2%) is unique to Luke, with no parallel in the earlier gospels of Mark and Matthew.[9]:109 [7]:87 They argue that this result is entirely expected if canonical Luke is the result of adding new material to Marcion's gospel or its source, but that it is very much unexpected if Marcion removed material from Luke.

Gospel of Marcion as the first gospel

Some proponents of the priority of Marcion's gospel have explored the implications of their view for the broader synoptic problem. In his 2013 book, The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon, Jason BeDuhn considers that the gospel of Marcion precedes all gospels. He considers that the Gospel of Marcion is the first of its kind, and that it was not produced or adapted by Marcion, but instead that the Gospel of Marcion was a collection of preexisting ancient Christian traditions compiled and adopted by Marcion and his movement.[10] He believes that: "On the whole, the differences between Luke and the Evangelion [i.e. the Gospel of Marcion] resist explanation on ideological grounds, and point instead toward Semler’s original suggestion 250 years ago: the two gospels could be alternative versions adapted for primarily Jewish and primarily Gentile readers, respectively. In other words, the differences served practical, mission-related purposes rather than ideological, sectarian ones. Under such a scenario, the Evangelion would be transmitted within exactly the wing of emerging Christianity in which we can best situate Marcion’s own religious background." Semler's hypothesis being that "the Evangelion and Luke are both pre-Marcionite versions going back to a common original."[11]

In his 2015 book, Matthias Klinghardt changed his mind comparing to his 2008 opinion. In 2008 he said that Marcion's gospel was based on the Gospel of Mark, that the Gospel of Matthew was an expansion of the Gospel of Mark with reference to the Gospel of Marcion, and that the Gospel of Luke was an expansion of the Gospel of Marcion with reference to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark.[5]:21–22, 26 In his 2015 book, Klingardht shares the same opinion as BeDuhn on the priority and influence of the Gospel of Marcion, as well as on its adoption by Marcion.[12][13] He considers that the Gospel of Marcion influenced the four gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John).[12] Klinghardt and BeDuhn reaffirmed their opinions in two 2017 articles.[14]

In his 2014 book Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels, Markus Vinzent considers, like BeDuhn and Klinghardt, that the gospel of Marcion precedes the four gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). He believes that the Gospel of Marcion influenced the four gospels. Vinzent differs with both BeDuhn and Klinghardt in that he believes the Gospel of Marcion was written directly by Marcion: Marcion's gospel was first written as a draft not meant for publication which was plagiarized by the four canonical gospels, this plagiarism angered Marcion who saw the purpose of his text distorted and made him publish his gospel along with a preface and 10 letters of Paul.[13][15][16]

The Marcion priority also implies a model of the late dating of the New Testament Gospels to the 2nd century – a thesis that goes back to David Trobisch, who, in 1996 in his habilitation thesis accepted in Heidelberg,[17] presented the conception or thesis of an early, uniform final editing of the New Testament canon in the 2nd century.[18]

See also

- Farrer hypothesis

- Gospel of Marcion

- Griesbach hypothesis

- Markan priority

- Synoptic problem

- Two-source hypothesis

Further reading

- Roth, Dieter T. (2008). "Marcion's Gospel and Luke the history of research in current debate". Journal of Biblical Literature. 127 (3): 513–521. doi:10.2307/25610137. JSTOR 25610137. OCLC 1074560351.

- Roth, Dieter T. (2015-03-11). "Roth on Vinzent on Marcion". Larry Hurtado's Blog. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- Guignard, Christophe (March 2013). "Marcion et les Évangiles canoniques. À propos d'un livre récent". Études théologiques et religieuses (in French). 88 (3): 347–363. doi:10.3917/etr.0883.0347 – via Cairn.info.

- Cassandra J. Farrin (2013-10-28). "Marcion: Forgotten "Father" and Inventor of the New Testament". Westar Institute. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- BeDuhn, Jason. "The New Marcion" (PDF). Forum. 3 (Fall 2015): 163–179.

- "Quaestiones Disputatae". New Testament Studies. 63 (2): 318–334. April 2017. Retrieved 2020-08-01 – via Cambridge Core.

References

- Price, Chris (2002-10-14). "Marcion, the Canon, the Law, and the Historical Jesus". christianorigins. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- Koestler, Helmut (1990). Ancient Christian Gospels: Their History and Development. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-334-02450-7.

- Tertullian[us], Quintus Septimius Florens. Adversus Marcionem (Against Marcion). pp. Book IV chap. 2 v. 3.

- Davis, Glenn (2007). "Marcion and the Marcionites (144 - 3rd century CE)". The Development of the Canon of the New Testament. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- Klinghardt, Matthias (2008). "The Marcionite Gospel and the Synoptic Problem: A New Suggestion". Novum Testamentum. 50 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1163/156853608X257527. JSTOR 25442581.

- BeDuhn, Jason (2013). "The Evangelion". The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- Tyson, Joseph (2006). Marcion and Luke-Acts: A Defining Struggle. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1570036507.

- Trobisch, David (2018). "The Gospel According to John in the Light of Marcion's Gospelbook". In Heilmann, Jan; Klinghardt, Matthias (eds.). Das Neue Testament und sein Text im 2.Jahrhundert. Texte und Arbeiten zum neutestamentlichen Zeitalter. 61. Tübingen, Germany: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag GmbH. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-3-7720-8640-3.

- Knox, John (1942). Marcion and the New Testament: An Essay in the Early History of the Canon. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN 978-0404161835.

- BeDuhn, Jason (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon. pp. 4–6, 9, 90. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

Nevertheless, we have it, in large part. We can expect to find no earlier New Testament in any form, for in fact it is the very first New Testament ever to have been made. Historians of Christianity widely acknowledge that Marcion (circa 95–165 CE) compiled the first authoritative collection of distinctly Christian writings from texts already known and valued by segments of the Christian movement.

[...]

As a second obstacle, study of Marcion’s New Testament has generally been subservient to investigations of Marcion as a theologian and key figure in Christian history. But Marcion did not compose these texts (even if there remains the separate question of whether he edited them to some degree); he collected them from a broader existing Christian movement, and bestowed them in their collected form back to living Christian communities. As we will see, there are good reasons to question the assumption that these texts were fundamentally altered for service only to Marcionite Christians.

[...]

These points of textual evidence and historical circumstance, therefore, suggest that Marcion may not have produced a definitive edition of the Evangelion after all, but rather took up a gospel already in circulation in multiple copies that had seen varying degrees of harmonization to other gospels in their transmission up to that point in time. The process of canonizing this gospel for the Marcionite community involved simply giving it a stamp of approval, acquiring copies already in circulation, and making more copies from these multiple exemplars, so that their varying degrees of harmonization passed into the Marcionite textual tradition of the Evangelion. - BeDuhn, Jason (2013). The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon. pp. 86, 91–92. ISBN 978-1-59815-131-2. OCLC 857141226.

- Klinghardt, Matthias (2015-03-25). "IV. Vom ältesten Evangelium zum kanonischen Vier-Evangelienbuch: Eine überlieferungsgeschichtliche Skizze". Das älteste Evangelium und die Entstehung der kanonischen Evangelien (in German). A. Francke Verlag. pp. 188–231. ISBN 978-3-7720-5549-2.

- Vinzent, Markus (2015). "Marcion's Gospel and the Beginnings of Early Christianity". Annali di Storia dell'esegesi. 32 (1): 55–87 – via Academia.edu.

- Gallagher, Ed (2017-03-14). "Marcion's Gospel and the New Testament". Our Beans. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- BeDuhn, Jason David (2015-09-16). "Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels, written by Markus Vinzent". Vigiliae Christianae. 69 (4): 452–457. doi:10.1163/15700720-12301234. ISSN 1570-0720.

- Vinzent, Markus (2016-11-24). "I am in the process of reading your book 'Marcion and the Dating of the Synoptic Gospels' ..." Markus Vinzent's Blog. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- David Trobisch: Die Endredaktion des Neuen Testamentes: eine Untersuchung zur Entstehung der christlichen Bibel. Universitäts-Verlag, Freiburg, Schweiz; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, zugl.: Heidelberg, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 1994, ISBN 3-525-53933-9 (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), ISBN 3-7278-1075-0 (Univ.-Verl.) (= Novum testamentum et orbis antiquus 31).

- Heilmann, Jan; Klinghardt, Matthias, eds. (2018). Das Neue Testament und sein Text im 2.Jahrhundert. Texte und Arbeiten zum neutestamentlichen Zeitalter. 61. Tübingen, Germany: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag GmbH. p. 9. ISBN 978-3-7720-8640-3.