Mario Merz

Mario Merz (1 January 1925 – 9 November 2003) was an Italian artist, and husband of Marisa Merz.

Mario Merz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 January 1925 |

| Died | 9 November 2003 (aged 78) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Sculpture and Painting |

| Movement | Arte Povera |

Life

Born in Milano, Merz started drawing during World War II, when he was imprisoned for his activities with the Giustizia e Libertà antifascist group. He experimented with a continuous graphic stroke–not removing his pencil point from the paper. He explored the relationship between nature and the subject, until he had his first exhibitions in the intellectually incendiary context of Turin in the 1950s, a cultural climate fed by such writers as Cesare Pavese, Elio Vittorini, and Ezra Pound.

He met Marisa Merz during his studies in Turin in the 1950s. They were associated with the development of Arte Povera, and they were both influenced by each other's works.

Work

Merz discarded abstract expressionism's subjectivity in favor of opening art to exterior space: a seed or a leaf in the wind becomes a universe on his canvas. From the mid-1960s, his paintings echoed his desire to explore the transmission of energy from the organic to the inorganic, a curiosity that led him to create works in which neon lights pierced everyday objects, such as an umbrella, a glass, a bottle or his own raincoat. Without ever using ready-made objects as "things" (at least to the extent that the Nouveau Realistes in France did), Merz and his companions drew the guiding lines of a renewed life for Italian art in the global context.

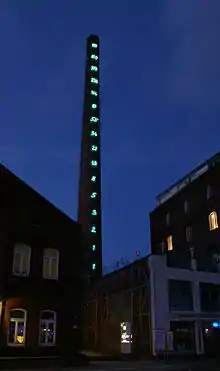

Many of his installations were accented with words or numbers in neon. The numbers counted off the Fibonacci progression, the mathematical formula (named for the Italian monk and mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci who discovered it) for growth patterns found in many forms of life, including leaves, snail shells, pine cones and reptile skins.[2] The pattern is identifiable as a sequence of numbers in which any given number is the sum of the two numbers that precede it: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, etc., ad infinitum.[3] From 1969 Merz employed the Fibonacci sequence in performances and installations throughout his career to represent the universal principles of creation and growth: climbing up the Guggenheim Museum in New York (1971) or the spire of a Turin landmark (1984), or perched in neon on a stack of newspapers among the old masters of Naples' Capodimonte Gallery (1987).[4] In 1972 he illustrated the Fibonacci progression with a series of photographs of a factory workers' lunchroom and a restaurant progressively crowded with diners. His 1973 show at the John Weber Gallery in New York expressed the Fibonacci in a series of low modular tables.[5] In 1990 the sequence determined the form of a spiral assembled from sticks, iron and paper across 24 meters of a hall in Prato, near Florence. An installation of Fibonacci numbers by Merz is the landmark of the Centre for International Light Art in Unna, Germany.

Merz became fascinated by architecture: he admired the skyscraper-builders of New York City; his father was an architect; and his art thereby conveys a sensitivity for the unity of space and the human residing therein. He made big spaces feel human, intimate and natural. He was intrigued by the powerful (Wagner, D’annunzio) as well as the small (a seed that will generate a tree or the shape of a leaf) and applied both to his drawing.

In the 1960s, Merz's work with energy, light and matter placed him in the movement that Germano Celant named Arte Povera, which, together with Futurism, was one of the most influential movements of Italian art in the 20th century. In 1968 Merz began to work on his famous igloos and continued throughout his life, revealing the prehistoric and tribal features hidden within the present time and space. He saw the mobility of this typical shelter for nomadic wandering as an ideal metaphor for the space of the artist.[6] The neon words on his igloos are hallmark Italian phraseology: like "rock ‘n’ roll," they have the power of being the more than catch phrases or slogans, but the voice of his time in history. His first of the dome-shaped structures, "Giap's Igloo," in 1968 was decorated with a saying by General Vo Nguyen Giap of North Vietnam: If the enemy masses his forces, he loses ground. If he scatters, he loses force.

By the time of his first solo museum exhibition in the United States, at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, in 1972, Merz had also added stacked newspapers, archetypal animals, and motorcycles to his iconography, to be joined later by the table, symbolizing a locus of the human need for fulfillment and interaction.[7]

From the late 1970s to the end of his career, Merz joined many artists of his generation in returning periodically to more conventional media. In Le Foglie (The Leaves) (1983–84), measuring over 26 feet across, gold leaf squares are scattered around two large asymmetrical leaf-like forms.[8] He even, occasionally, carved in marble, with which in 2002 he made five statues displayed from the windows of a building at the International Sculpture Biennale in Carrara. Merz said: "Space is curved, the earth is curved, everything on earth is curved" and subsequently produced large curvilinear installations like the one at the Guggenheim in New York. This retrospective was the artist's first major museum show in the United States. These last works are formally transcendent and unusually light. His site-specific works in archaeological sites redeem spaces from touristy tedium with a single neon line, which serves as source of aesthetic inspiration. He had the wild, immediate perceptiveness of a child. His works encapsulate this nature together with an uncanny universality and versatility.

In 1996, Merz collaborated with Jil Sander on a fashion show, including a wind tunnel of sheer white fabric twisted and filled with blowing leaves.[9] Along with six other collaborations between artists and fashion designers on the occasion of the first Biennale of Florence that same year, Merz and Sander were assigned an individual pavilion designed by architect Arata Isozaki. Merz and Sander transformed their pavilion, which was open to the outside, into a wind tunnel inspired by the form of a 10-foot diameter cylinder. One end of the tunnel was fitted with an oculus through which the viewer could gaze into a vortex of blowing leaves and flowers through the length of a suspended fabric cone.[10]

Exhibitions

Merz had his first one-man exhibition, in 1954, at the Galleria La Bussola in Turin;[11] his first solo European museum exhibition took place at the Kunsthalle Basel in 1975. He has since been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions at institutions around the world, including Fundação de Serralves, Porto; Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London (1975); Moderna Museet, Stockholm (1983); Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg; Fundación Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona; Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1989); a two-venue retrospective at Castello di Rivoli and Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Turin (2005). In the years 1972, 1977, 1983 and 1992 Mario Merz participated in the documenta 5, 6, 7 and 9. In 1989, his work "Se la forma scompare la sua radice è eterna" was installed at the Deichtorhallen.

Recognition

Merz was awarded the Ambrogino Gold Prize, Milan; the Oskar Kokoschka Prize, Vienna; the Arnold Bode Prize, Kassel; and the Praemium Imperiale for sculpture (2003). He was the subject of an atmospheric film, Mario Merz (2002), shot during the summer of 2002 in San Gimignano by the British artist Tacita Dean. The Fondazione Merz in Turin, Italy, regularly displays both the works of its namesake and sponsors exhibitions by living artists.

Collections

- Centre for International Light Art (CILA), Unna, Germany

- Hallen für Neue Kunst Schaffhausen, Switzerland

Legacy

The Fondazione Merz was founded in 2005 in Turin, Italy, by Mario Merz's daughter Beatrice.[12] The Mario Merz Prize was launched in 2015.[13]

References

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1447610/Mario-Merz.html

- Roberta Smith (November 13, 2003), Mario Merz, 78, an Italian Installation Artist New York Times.

- Mario Merz, September 18, 2008 - January 6, 2009 Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Gladstone Gallery, New York.

- Christopher Masters (November 13, 2003), Obituary: Mario Merz The Guardian.

- Roberta Smith (November 13, 2003), Mario Merz, 78, an Italian Installation Artist New York Times.

- Mario Merz, September 18, 2008 - January 6, 2009 Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Gladstone Gallery, New York.

- Biography: Mario Merz Guggenheim Collection.

- Mario Merz: Major Works from the 1980s, 1 November - 22 December 2012 Archived 30 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine Sperone Westwater, New York.

- Amy Spindler (October 8, 1996), When Designers Take Cues From Art New York Times.

- Heinz Peter Schwerfel (December 1996), Die Mode geht, aber die Kunst bleibt art – Das Kunstmagazin.

- Christopher Masters (November 13, 2003), Obituary: Mario Merz The Guardian.

- "The Foundation Dedicated to Mario and Marisa Merz Had Big Plans to Celebrate Its Anniversary in Italy. Then the Pandemic Hit". artnet News. 2020-04-29. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

- "Shortlisted Artists 2017 Mario Merz Prize". artnet News. 2016-06-11. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

Literature

- Christel Sauer: Mario Merz: Isola della Frutta, Raussmüller Collection, Basel 2009, ISBN 978-3-905777-02-4

- Christel Sauer: Mario Merz: Architettura fondata dal tempo, architettura sfondata dal tempo, Raussmüller Collection, Basel 2009, ISBN 978-3-905777-03-1

- Christel Sauer: Mario Merz: Le braccia lunghe della preistoria, Raussmüller Collection, Basel 2009, ISBN 978-3-905777-04-8

- Christel Sauer: Mario Merz: Casa sospesa, Raussmüller Collection, Basel 2009, ISBN 978-3-905777-05-5

- Meret Arnold: Mario Merz: My home's wind, Raussmüller Collection, Basel 2011, ISBN 978-3-905777-07-9

- Christel Sauer: Mario Merz: Senza titolo, Raussmüller Collection, Basel 2011, ISBN 978-3-905777-08-6

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mario Merz |