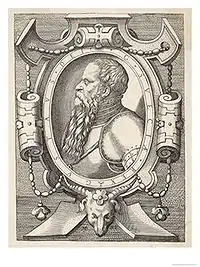

Martino Rota

Martino Rota, also Martin Rota and Martin Rota Kolunić (c. 1520–1583) was an artist, now mainly known for his printmaking, from Dalmatia.[1][2]

Martino Rota was born in about the year 1520 in Šibenik (Sebenico), Dalmatia. Little is known of Rota's early life or where he trained as an engraver, but most of his documented career was spent working in Venice, Rome, and Vienna.[2][3]

Life

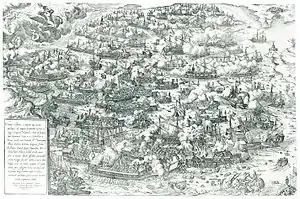

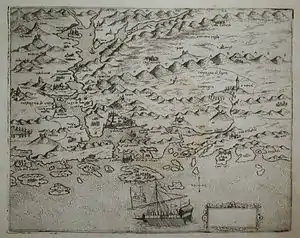

In about 1540, Rota appears in Rome, working as a reproductive engraver in the style of Marcantonio, and employed by, or collaborating with, Cornelis Cort. At some point he left Rome and after a period in Florence was in Venice from 1558, where it has been argued that he substituted for Cort, absent from Venice from 1566-1571, as Titian's reproductive engraver - always a difficult and demanding role - although this is controversial, as none of his prints after Titian mention below the image the 15 year copyright "privilege" granted to Titian by the Senate and referred to on Cort's prints after Titian.[4] He also produced several maps and views of Venice and other cities.[5]

Perhaps with Titian's recommendation, he moved to the Imperial court in Vienna, where he arrived by 1568,[6][7] and by 1573 he was established as the court portrait engraver. From this time he made fewer reproductive prints, and concentrated on portraiture of the Imperial family, often using assistants as not all the later prints show the fine technical quality of his earlier work.[8] He served the Habsburgs in Vienna during the reigns of Maximilian II and Rudolph II, the second of whom became Emperor in 1576. Rudolf moved the Habsburg capital from Vienna to Prague in 1583, where Rota died the same year.[3][9]

Work

Rota has been described as one of the most significant graphic artists of the second half of the 16th century,[3] though few if any of his prints were original compositions.

Chiefly an engraver of portraits, which he also painted, his drafting of the human figure is very correct, and he pays particular attention to extremities. He engraved plates entirely with the graving tool.[2] Rota showed Durerian naturalism and a Venetian feeling for material.[9] Like many printmakers of the period, he combined etching and engraving on the same plates, but in an unusually sensitive manner, exploiting the differences between the two techniques.[10]

He also engraved paintings by masters of the Renaissance, in particular Titian, whose very important destroyed altarpiece of the Martyrdom of St. Peter Martyr is now best known from Rota's engraving;[11] he also made engravings after work by Michelangelo and Dürer. His known work includes more than one hundred and seventy engravings and etchings on a variety of subjects, including maps, vedutes, portraits, illustrations for pamphlets, coats of arms, and depictions of the saints. He added to the fame of Šibenik and of his compatriot Antun Vrančić, called Antonius Verantius.[3][9]

The art collector George Cumberland wrote in 1827 that[12]

...if such men as Martin Rota, Cort, Bloemart,[13] or Goltzius, did not often adhere to the style and character of head of the Artist they copied, yet they always gave enough to enable us to comprehend the principles of the composition; and we often have well drawn figures to make us some amends for the loss of sentiment in the heads, expression of hands, or local colouring.

Rota's portrait of the Emperor Ferdinand I (1503–1564), pictured, may have been engraved from Deschler's medallion of 1561.[3] Other portraits he engraved include the Emperors Maximilian II and Rudolf II and King Henry IV of France.[2]

His masterpiece is considered to be an engraving after Michelangelo's The Last Judgment.[2]

Rota was active until his death in 1583, leaving a small number of plates incomplete, which were completed by his pupil Anselmus de Boodt.[14]

Signature

Rota usually signed his plates with his name, sometimes adding the names Sebenico and Venice,[15] but he sometimes used a monogram consisting of a capital 'M' and a pictogram of a wheel (Rota means 'wheel' in Latin).[2] The monogram is illustrated in Stefano Ticozzi's monumental Dizionario of 1830–1833.[16]

Exhibitions

From March to April 2003, an exhibition in the Print Department of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Zagreb, focused on works by Rota and by another native of Šibenik, Natale Bonifacio, held in Croatian collections.[9]

Gallery

Carolus Clusius

Notes

- Getty Union Artist Name List

- Bryan, Michael, (revised by George Stanley) A Biographical and Critical Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, from the revival of the art under Cimabue, and the alleged discovery of engraving by Finiguerra, to the present time (London, H G. Bohn, 1849), page 662 online at books.google.co.uk (accessed 4 March 2008)

- Treasures — National and University Library, Zagreb online at theeuropeanlibrary.org (accessed 4 March 2008)

- Bury, 190-91

- Concise Grove, and Reed and Wallace

- Reed & Wallace, 58

- Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe, Copyright in the Renaissance: Prints and the Privilegio in sixteenth-century Venice and Rome 2004.

- Reed and Wallace, op & page cit

- Three Engravers from Šibenik Archived 2004-05-23 at Archive.today at www.canvas.hr, accessed 15 July 2008

- Reed and Wallace, 60

- Catalogue entry at Bury, 191

- Cumberland, George, An Essay on the Utility of Collecting the Best Works of the Ancient Engravers of the Italian School (London, Payne and Foss, 1827) page 6 online at books.google.co.uk, accessed 12 July 2008

- Either Abraham Bloemaert or Cornelis Bloemaert may have been intended.

- Martino Rota (Sebenico 1520 – Vienna 1583), Il riposo dalla Fuga in Egitto, in: Grafica Antica catalogo n° 49, p. 36.

- Reed & Wallace

- Ticozzi, Stefano, Dizionario degli architetti, scultori, pittori, intagliatori in rame ed in pietra, coniatori di medaglie, musaicisti, niellatori, intarsiatori d'ogni età e d'ogni nazione (3 volumes, Milan, 1830–1833)

References

- Bury, Michael; The Print in Italy, 1550-1620, 2001, British Museum Press, ISBN 0-7141-2629-2

- Reed, Sue Welsh & Wallace, Richard (eds), Italian Etchers of the Renaissance and Baroque, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1989,pp 58–60,ISBN 0-87846-306-2 or 304-4 (pb)

- Bergquist, Stephen A, "Some Early States by Martino Rota," Print Quarterly, XXIX, no. 1, 2012, pp.33-36.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Martino Rota. |