Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (pronounced [titˈtsjaːno veˈtʃɛlljo]; c. 1488/90[1] – 27 August 1576),[2] known in English as Titian (/ˈtɪʃən/ TISH-ən), was an Italian painter during the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno, (then in the Republic of Venice).[3] During his lifetime he was often called da Cadore, 'from Cadore', taken from his native region.[4]

Titian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Tiziano Vecellio c. 1488/90 |

| Died | 27 August 1576 (aged 87–88) Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Nationality | Venetian |

| Occupation | Italian Renaissance artist |

| Signature | |

| |

Recognized by his contemporaries as "The Sun Amidst Small Stars" (recalling the final line of Dante's Paradiso), Titian was one of the most versatile of Italian painters, equally adept with portraits, landscape backgrounds, and mythological and religious subjects. His painting methods, particularly in the application and use of colour, exercised a profound influence not only on painters of the late Italian Renaissance, but on future generations of Western art.[5]

His career was successful from the start, and he became sought after by patrons, initially from Venice and its possessions, then joined by the north Italian princes, and finally the Habsburgs and papacy. Along with Giorgione, he is considered a founder of the Venetian School of Italian Renaissance painting.

During the course of his long life, Titian's artistic manner changed drastically,[6] but he retained a lifelong interest in colour. Although his mature works may not contain the vivid, luminous tints of his early pieces, their loose brushwork and subtlety of tone were without precedent in the history of Western painting.

Biography

Early years

The exact time or date of Titian's birth is uncertain. When he was an old man he claimed in a letter to Philip II, King of Spain, to have been born in 1474, but this seems most unlikely.[7] Other writers contemporary to his old age give figures that would equate to birthdates between 1473 and after 1482.[8] Most modern scholars believe a date between 1488 and 1490 is more likely,[9] though his age at death being 99 had been accepted into the 20th century.[10]

He was the son of Gregorio Vecellio and his wife Lucia, of whom little is known. Gregorio was superintendent of the castle of Pieve di Cadore and managed local mines for their owners.[11] Gregorio was also a distinguished councilor and soldier. Many relatives, including Titian's grandfather, were notaries, and the family were well-established in the area, which was ruled by Venice.

At the age of about ten to twelve he and his brother Francesco (who perhaps followed later) were sent to an uncle in Venice to find an apprenticeship with a painter. The minor painter Sebastian Zuccato, whose sons became well-known mosaicists, and who may have been a family friend, arranged for the brothers to enter the studio of the elderly Gentile Bellini, from which they later transferred to that of his brother Giovanni Bellini.[11] At that time the Bellinis, especially Giovanni, were the leading artists in the city. There Titian found a group of young men about his own age, among them Giovanni Palma da Serinalta, Lorenzo Lotto, Sebastiano Luciani, and Giorgio da Castelfranco, nicknamed Giorgione. Francesco Vecellio, Titian's older brother, later became a painter of some note in Venice.

A fresco of Hercules on the Morosini Palace is said to have been one of Titian's earliest works.[4] Others were the Bellini-esque so-called Gypsy Madonna in Vienna,[12] and the Visitation of Mary and Elizabeth (from the convent of S. Andrea), now in the Accademia, Venice.[4]

A Man with a Quilted Sleeve is an early portrait, painted around 1509 and described by Giorgio Vasari in 1568. Scholars long believed it depicted Ludovico Ariosto, but now think it is of Gerolamo Barbarigo.[13] Rembrandt borrowed the composition for his self-portraits.

Titian joined Giorgione as an assistant, but many contemporary critics already found his work more impressive—for example in exterior frescoes (now almost totally destroyed) that they did for the Fondaco dei Tedeschi (state-warehouse for the German merchants).[4] Their relationship evidently contained a significant element of rivalry. Distinguishing between their work at this period remains a subject of scholarly controversy. A substantial number of attributions have moved from Giorgione to Titian in the 20th century, with little traffic the other way. One of the earliest known Titian works, Christ Carrying the Cross in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, depicting the Ecce Homo scene,[14] was long regarded as by Giorgione.[15]

The two young masters were likewise recognized as the leaders of their new school of arte moderna, which is characterized by paintings made more flexible, freed from symmetry and the remnants of hieratic conventions still found in the works of Giovanni Bellini.

In 1507–1508 Giorgione was commissioned by the state to create frescoes on the re-erected Fondaco dei Tedeschi. Titian and Morto da Feltre worked along with him, and some fragments of paintings remain, probably by Giorgione.[4] Some of their work is known, in part, through the engravings of Fontana. After Giorgione's early death in 1510, Titian continued to paint Giorgionesque subjects for some time, though his style developed its own features, including bold and expressive brushwork.

Titian's talent in fresco is shown in those he painted in 1511 at Padua in the Carmelite church and in the Scuola del Santo, some of which have been preserved, among them the Meeting at the Golden Gate, and three scenes (Miracoli di sant'Antonio) from the life of St. Anthony of Padua, The Miracle of the Jealous Husband, which depicts the Murder of a Young Woman by Her Husband,[16] A Child Testifying to Its Mother's Innocence, and The Saint Healing the Young Man with a Broken Limb.

In 1512 Titian returned to Venice from Padua; in 1513 he obtained La Senseria (a profitable privilege much coveted by artists) in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi.[17] He became superintendent of the government works, especially charged with completing the paintings left unfinished by Giovanni Bellini in the hall of the great council in the ducal palace. He set up an atelier on the Grand Canal at S. Samuele, the precise site being now unknown. It was not until 1516, after the death of Giovanni Bellini, that he came into actual enjoyment of his patent. At the same time he entered an exclusive arrangement for painting. The patent yielded him a good annuity of 20 crowns and exempted him from certain taxes. In return, he was bound to paint likenesses of the successive Doges of his time at the fixed price of eight crowns each. The actual number he painted was five.[4]

Growth

During this period (1516–1530), which may be called the period of his mastery and maturity, the artist moved on from his early Giorgionesque style, undertook larger, more complex subjects, and for the first time attempted a monumental style. Giorgione died in 1510 and Giovanni Bellini in 1516, leaving Titian unrivaled in the Venetian School. For sixty years he was the undisputed master of Venetian painting. In 1516, he completed his famous masterpiece, the Assumption of the Virgin, for the high altar of the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari,[4] where it is still in situ. This extraordinary piece of colourism, executed on a grand scale rarely before seen in Italy, created a sensation.[18] The Signoria took note and observed that Titian was neglecting his work in the hall of the great council,[4] but in 1516 he succeeded his master Giovanni Bellini in receiving a pension from the Senate.[19]

The pictorial structure of the Assumption—that of uniting in the same composition two or three scenes superimposed on different levels, earth and heaven, the temporal and the infinite—was continued in a series of works such as the retable of San Domenico at Ancona (1520), the retable of Brescia (1522), and the retable of San Niccolò (1523), in the Vatican Museums, each time attaining to a higher and more perfect conception. He finally reached a classic formula in the Pesaro Madonna, better known as the Madonna di Ca' Pesaro (c. 1519–1526), also for the Frari church. This is perhaps his most studied work, whose patiently developed plan is set forth with supreme display of order and freedom, originality and style. Here Titian gave a new conception of the traditional groups of donors and holy persons moving in aerial space, the plans and different degrees set in an architectural framework.[20]

Titian was then at the height of his fame, and towards 1521, following the production of a figure of St. Sebastian for the papal legate in Brescia (of which there are numerous replicas), purchasers pressed for his work.[4]

To this period belongs a more extraordinary work, The Death of St. Peter Martyr (1530), formerly in the Dominican Church of San Zanipolo, and destroyed by an Austrian shell in 1867. Only copies and engravings of this proto-Baroque picture remain. It combined extreme violence and a landscape, mostly consisting of a great tree, that pressed into the scene and seems to accentuate the drama in a way that looks forward to the Baroque.[21]

The artist simultaneously continued a series of small Madonnas, which he placed amid beautiful landscapes, in the manner of genre pictures or poetic pastorals. The Virgin with the Rabbit, in The Louvre, is the finished type of these pictures. Another work of the same period, also in the Louvre, is the Entombment. This was also the period of the three large and famous mythological scenes for the camerino of Alfonso d'Este in Ferrara, The Bacchanal of the Andrians and the Worship of Venus in the Museo del Prado, and the Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–23) in London,[22] "perhaps the most brilliant productions of the neo-pagan culture or "Alexandrianism" of the Renaissance, many times imitated but never surpassed even by Rubens himself."[23]

Finally this was the period when Titian composed the half-length figures and busts of young women, probably courtesans, such as Flora of the Uffizi, or Woman with a Mirror in the Louvre (the scientific images of this painting are available, with explanations, on the website of the French Center for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France)

Maturity

Titian's skill with colour is exemplified by his Danaë, one of several mythological paintings, or "poesie" ("poems") as the painter called them. This painting was done for Alessandro Farnese, but a later variant was produced for Philip II, for whom Titian painted many of his most important mythological paintings. Although Michelangelo adjudged this piece deficient from the point of view of drawing, Titian and his studio produced several versions for other patrons.

Another famous painting is Bacchus and Ariadne, depicting Theseus, whose ship is shown in the distance and who has just left Ariadne at Naxos, when Bacchus arrives, jumping from his chariot, drawn by two cheetahs, and falling immediately in love with Ariadne. Bacchus raised her to heaven. Her constellation is shown in the sky. The painting belongs to a series commissioned from Bellini, Titian, and Dosso Dossi, for the Camerino d'Alabastro (Alabaster Room) in the Ducal Palace, Ferrara, by Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, who in 1510 even tried to commission Michelangelo and Raphael.

During the next period (1530–1550), Titian developed the style introduced by his dramatic Death of St. Peter Martyr. In 1538, the Venetian government, dissatisfied with Titian's neglect of his work for the ducal palace, ordered him to refund the money he had received, and Il Pordenone, his rival of recent years, was installed in his place. However, at the end of a year Pordenone died, and Titian, who meanwhile applied himself diligently to painting in the hall the Battle of Cadore, was reinstated.[4]

This major battle scene was lost—with many other major works by Venetian artists—in the 1577 fire that destroyed all the old pictures in the great chambers of the Doge's Palace. It depicted in life-size the moment when the Venetian general d'Alviano attacked the enemy, with horses and men crashing down into a stream.[4] It was Titian's most important attempt at a tumultuous and heroic scene of movement to rival Raphael's Battle of Constantine, Michelangelo's equally ill-fated Battle of Cascina, and Leonardo da Vinci's The Battle of Anghiari (these last two unfinished). There remains only a poor, incomplete copy at the Uffizi, and a mediocre engraving by Fontana. The Speech of the Marquis del Vasto (Madrid, 1541) was also partly destroyed by fire. But this period of the master's work is still represented by the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin (Venice, 1539), one of his most popular canvasses, and by the Ecce Homo (Vienna, 1541). Despite its loss, the painting had a great influence on Bolognese art and Rubens, both in the handling of details and the general effect of horses, soldiers, lictors, powerful stirrings of crowds at the foot of a stairway, lit by torches with the flapping of banners against the sky.

Less successful were the pendentives of the cupola at Santa Maria della Salute (Death of Abel, Sacrifice of Abraham, David and Goliath). These violent scenes viewed in perspective from below were by their very nature in unfavorable situations. They were nevertheless much admired and imitated, Rubens among others applying this system to his forty ceilings (the sketches only remain) of the Jesuit church at Antwerp.

At this time also, during his visit to Rome, the artist began a series of reclining Venuses: The Venus of Urbino of the Uffizi, Venus and Love at the same museum, Venus—and the Organ-Player, Madrid, which shows the influence of contact with ancient sculpture. Giorgione had already dealt with the subject in his Dresden picture, finished by Titian, but here a purple drapery substituted for a landscape background changed, by its harmonious colouring, the whole meaning of the scene.

From the beginning of his career, Titian was a masterful portrait-painter, in works like La Bella (Eleanora de Gonzaga, Duchess of Urbino, at the Pitti Palace). He painted the likenesses of princes, or Doges, cardinals or monks, and artists or writers. "...no other painter was so successful in extracting from each physiognomy so many traits at once characteristic and beautiful".[24] Among portrait-painters Titian is compared to Rembrandt and Velázquez, with the interior life of the former, and the clearness, certainty, and obviousness of the latter.

These qualities show in the Portrait of Pope Paul III of Naples, or the sketch of the same Pope Paul III and his Grandsons, the Portrait of Pietro Aretino of the Pitti Palace, the Portrait of Isabella of Portugal (Madrid), and the series of Emperor Charles V of the same museum, the Charles V with a Greyhound (1533), and especially the Equestrian Portrait of Charles V (1548), an equestrian picture in a symphony of purples. This state portrait of Charles V (1548) at the Battle of Mühlberg established a new genre, that of the grand equestrian portrait. The composition is steeped both in the Roman tradition of equestrian sculpture and in the medieval representations of an ideal Christian knight, but the weary figure and face have a subtlety few such representations attempt. In 1532, after painting a portrait of the emperor Charles V in Bologna, he was made a Count Palatine and knight of the Golden Spur. His children were also made nobles of the Empire, which for a painter was an exceptional honor.[4]

As a matter of professional and worldly success, his position from about this time is regarded as equal only to that of Raphael, Michelangelo and, at a later date, Rubens. In 1540 he received a pension from d'Avalos, marquis del Vasto, and an annuity of 200 crowns (which was afterwards doubled) from Charles V from the treasury of Milan. Another source of profit, for he was always aware of money, was a contract obtained in 1542 for supplying grain to Cadore, where he visited almost every year and where he was both generous and influential.[4]

Titian had a favorite villa on the neighboring Manza Hill (in front of the church of Castello Roganzuolo) from which (it may be inferred) he made his chief observations of landscape form and effect. The so-called Titian's mill, constantly discernible in his studies, is at Collontola, near Belluno.[25][4]

He visited Rome in 1546 and obtained the freedom of the city—his immediate predecessor in that honor having been Michelangelo in 1537. He could at the same time have succeeded the painter Sebastiano del Piombo in his lucrative office as holder of the piombo or Papal seal, and he was prepared to take Holy Orders for the purpose; but the project lapsed through his being summoned away from Venice in 1547 to paint Charles V and others in Augsburg. He was there again in 1550, and executed the portrait of Philip II, which was sent to England and was useful in Philip's suit for the hand of Queen Mary.[4]

Final years

During the last twenty-six years of his life (1550–1576), Titian worked mainly for Philip II and as a portrait-painter. He became more self-critical, an insatiable perfectionist, keeping some pictures in his studio for ten years—returning to them and retouching them, constantly adding new expressions at once more refined, concise, and subtle. He also finished many copies that his pupils made of his earlier works. This caused problems of attribution and priority among versions of his works—which were also widely copied and faked outside his studio during his lifetime and afterwards.

For Philip II, he painted a series of large mythological paintings known as the "poesie", mostly from Ovid, which scholars regard as among his greatest works.[26] Thanks to the prudishness of Philip's successors, these were later mostly given as gifts, and only two remain in the Prado. Titian was producing religious works for Philip at the same time, some of which—the ones inside Ribeira Palace—are known to have been destroyed during the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake. The "poesie" series contained the following works:

- Danaë, sent to Philip in 1553,[27] now Wellington Collection, with earlier and later versions

- Venus and Adonis, of which the earliest surviving version, delivered in 1554, is in the Prado, but several versions exist

- Perseus and Andromeda (Wallace Collection, now damaged)

- Diana and Actaeon, owned jointly by London's National Gallery and the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh

- Diana and Callisto, were dispatched in 1559, owned jointly by London's National Gallery and the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh

- The Rape of Europa (Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum), delivered in 1562

- The Death of Actaeon, begun in 1559 but worked on for many years and never completed or delivered[28]

- Titian's poesie series for Philip II

Another painting that apparently remained in his studio at his death, and has been much less well known until recent decades, is the powerful, even "repellent" Flaying of Marsyas (Kroměříž, Czech Republic).[29] Another violent masterpiece is Tarquin and Lucretia (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum).[30]

For each problem he undertook, he furnished a new and more perfect formula. He never again equaled the emotion and tragedy of The Crowning with Thorns (Louvre); in the expression of the mysterious and the divine he never equaled the poetry of the Pilgrims of Emmaus; while in superb and heroic brilliancy he never again executed anything more grand than The Doge Grimani adoring Faith (Venice, Doge's Palace), or the Trinity, of Madrid. On the other hand, from the standpoint of flesh tints, his most moving pictures are those of his old age, such as the poesie and the Antiope of the Louvre. He even attempted problems of chiaroscuro in fantastic night effects (Martyrdom of St. Laurence, Church of the Jesuits, Venice; St. Jerome, Louvre; Crucifixion, Church of San Domenico, Ancona).

Titian had engaged his daughter Lavinia, the beautiful girl whom he loved deeply and painted various times, to Cornelio Sarcinelli of Serravalle. She had succeeded her aunt Orsa, then deceased, as the manager of the household, which, with the lordly income that Titian made by this time, placed her on a corresponding footing. Lavinia's marriage to Cornelio took place in 1554. She died in childbirth in 1560.[4]

Titian was at the Council of Trent towards 1555, of which there is a finished sketch in the Louvre. His friend Aretino died suddenly in 1556, and another close intimate, the sculptor and architect Jacopo Sansovino, in 1570. In September 1565 Titian went to Cadore and designed the decorations for the church at Pieve, partly executed by his pupils. One of these is a Transfiguration, another an Annunciation (now in S. Salvatore, Venice), inscribed Titianus fecit, by way of protest (it is said) against the disparagement of some persons who caviled at the veteran's failing handicraft.[4]

Around 1560,[31] Titian painted the oil on canvas Madonna and Child with Saints Luke and Catherine of Alexandria, a derivative on the motif of Madonna and Child. It is suggested that members of Titian's Venice workshop probably painted the curtain and Luke, because of the lower quality of those parts.[32]

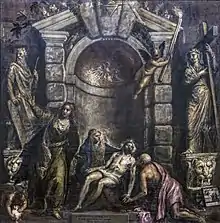

He continued to accept commissions to the end of his life. Like many of his late works, Titian's last painting, the Pietà, is a dramatic, nocturnal scene of suffering. He apparently intended it for his own tomb chapel. He had selected, as his burial place, the chapel of the Crucifix in the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, the church of the Franciscan Order. In payment for a grave, he offered the Franciscans a picture of the Pietà that represented himself and his son Orazio, with a sibyl, before the Savior. He nearly finished this work, but differences arose regarding it, and he settled on being interred in his native Pieve.[4]

Death

_nave_right_-_Monument_of_Titian.jpg.webp)

While the plague raged in Venice, Titian died of a fever on 27 August 1576.[33] Depending on his unknown birthdate (see above), he was somewhere from his late eighties or even close to 100. Titian was interred in the Frari (Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari), as at first intended, and his Pietà was finished by Palma il Giovane. He lies near his own famous painting, the Madonna di Ca' Pesaro. No memorial marked his grave.[4] Much later the Austrian rulers of Venice commissioned Antonio Canova to sculpt the large monument still in the church.

Very shortly after Titian's death, his son, assistant and sole heir Orazio, also died of the plague, greatly complicating the settlement of his estate, as he had made no will.[34]

Printmaking

Titian never attempted engraving, but he was very conscious of the importance of printmaking as a means to expand his reputation. In the period 1517–1520 he designed a number of woodcuts, including an enormous and impressive one of The Crossing of the Red Sea, intended as wall decoration in substitute for paintings;[35] and collaborated with Domenico Campagnola and others, who produced additional prints based on his paintings and drawings. Much later he provided drawings based on his paintings to Cornelis Cort from the Netherlands who engraved them. Martino Rota followed Cort from about 1558 to 1568.[36]

Painting materials

Titian employed an extensive array of pigments and it can be said that he availed himself of virtually all available pigments of his time.[37] In addition to the common pigments of the Renaissance period, such as ultramarine, vermilion, lead-tin yellow, ochres, and azurite, he also used the rare pigments realgar and orpiment.[38]

Family and workshop

Titian's wife, Cecilia, was a barber's daughter from his hometown village of Cadore. As a young woman she had been his housekeeper and mistress for some five years. Cecilia had already borne Titian two fine sons, Pomponio and Orazio, when in 1525 she fell seriously ill. Titian, wishing to legitimize the children, married her. Cecilia recovered, the marriage was a happy one, and they had another daughter who died in infancy.[39] In August 1530 Cecilia died. Titian remarried, but little information is known about his second wife; she was possibly the mother of his daughter Lavinia.[40] Titian had a fourth child, Emilia, the result of an affair, possibly with a housekeeper.[41] His favourite child was Orazio, who became his assistant.

In August 1530, Titian moved his two boys and infant daughter to a new home and convinced his sister Orsa to come from Cadore and take charge of the household. The mansion, difficult to find now, is in the Biri Grande, then a fashionable suburb, at the extreme end of Venice, on the sea, with beautiful gardens and a view towards Murano. In about 1526 he had become acquainted, and soon close friends, with Pietro Aretino, the influential and audacious figure who features so strangely in the chronicles of the time. Titian sent a portrait of him to Gonzaga, duke of Mantua.[4]

When he was very young, the famed Italian painter Tintoretto was brought to Titian's studio by his father. This was supposedly around 1533, when Titian was (according to the ordinary accounts) over 40 years of age. Tintoretto had only been ten days in the studio when Titian sent him home for good, because the great master observed some very spirited drawings, which he learned to be the production of Tintoretto; it is inferred that he became at once jealous of so promising a student. This, however, is mere conjecture; and perhaps it may be fairer to suppose that the drawings exhibited so much independence of manner that Titian judged that young Jacopo, although he might become a painter, would never be properly a pupil.[42] From this time forward the two always remained upon distant terms, though Tintoretto being indeed a professed and ardent admirer of Titian, but never a friend, and Titian and his adherents turned a cold shoulder to him. There was also active disparagement, but it passed unnoticed by Tintoretto.

Several other artists of the Vecelli family followed in the wake of Titian. Francesco Vecellio, his older brother, was introduced to painting by Titian (it is said at the age of twelve, but chronology will hardly admit of this), and painted in the church of S. Vito in Cadore a picture of the titular saint armed. This was a noteworthy performance, of which Titian (the usual story) became jealous; so Francesco was diverted from painting to soldiering, and afterwards to mercantile life.[4]

Marco Vecellio, called Marco di Tiziano, born in 1545, was Titian's nephew and was constantly with the master in his old age, and learned his methods of work. He has left some able productions in the ducal palace, the Meeting of Charles V. and Clement VII. in 1529; in S. Giacomo di Rialto, an Annunciation; in SS. Giovani e Paolo, Christ Fulminant. A son of Marco, named Tiziano (or Tizianello), painted early in the 17th century.[4]

From a different branch of the family came Fabrizio di Ettore, a painter who died in 1580. His brother Cesare, who also left some pictures, is well known by his book of engraved costumes, Abiti antichi e moderni. Tommaso Vecelli, also a painter, died in 1620. There was another relative, Girolamo Dante, who, being a scholar and assistant of Titian, was called Girolamo di Tiziano. Various pictures of his were touched up by the master, and are difficult to distinguish from originals.[4]

Few of the pupils and assistants of Titian became well known in their own right; for some being his assistant was probably a lifetime career. Paris Bordone and Bonifazio Veronese were his assistants during at some point in their careers. Giulio Clovio said Titian employed El Greco (or Dominikos Theotokopoulos) in his last years. Polidoro da Lanciano is said to have been a follower or pupil of Titian. Other followers were Nadalino da Murano,[43] Damiano Mazza,[44] and Gaspare Nervesa.[45]

Present day

Contemporary estimates attribute around 400 works to Titian, of which about 300 survive.[46] Two of Titian's works in private hands were put up for sale in 2008. One of these, Diana and Actaeon, was purchased by London's National Gallery and the National Galleries of Scotland on 2 February 2009 for £50 million.[47] The galleries had until 31 December 2008 to make the purchase before the work would be offered to private collectors, but the deadline was extended. The other painting, Diana and Callisto, was for sale for the same amount until 2012 before it was offered to private collectors. The sale created controversy with politicians who argued that the money could have been spent more wisely during a deepening recession. The Scottish Government offered £12.5 million and £10 million came from the National Heritage Memorial Fund. The rest of the money came from the National Gallery and from private donations.[48]

Gallery of works

_-_Interior_-_Annunciation_by_Titian.jpg.webp) Annunciation, 1519–1520, oil on canvas; altar-painting in the Treviso Cathedral

Annunciation, 1519–1520, oil on canvas; altar-painting in the Treviso Cathedral.jpg.webp)

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) The Aldobrandini Madonna, c 1530

The Aldobrandini Madonna, c 1530

A monk with a book, c. 1550

A monk with a book, c. 1550

_-_Pale_d%E2%80%99altare_-_Apostolo_Giacomo_il_maggiore_-_Tiziano_-_1558.jpg.webp) Altarpiece of James the Greater, 1558, altar-painting in the San Lio church, Venice

Altarpiece of James the Greater, 1558, altar-painting in the San Lio church, Venice Annunciation of the Lord, 1559–1564, oil on canvas; altar-painting in the San Savator church, Venice

Annunciation of the Lord, 1559–1564, oil on canvas; altar-painting in the San Savator church, Venice Tarquin and Lucretia, 1571

Tarquin and Lucretia, 1571

Notes

- See below; c. 1488/1490 is generally accepted despite claims in his lifetime that he was older, Getty Union Artist Name List and Metropolitan Museum of Art timeline, retrieved 11 February 2009 both use c. 1488. See discussion of the issue below and at When Was Titian Born?, which sets out the evidence, and supports 1477—an unusual view today. Gould (pp. 264–66) also sets out much of the evidence without coming to a conclusion. Charles Hope in Jaffé (p. 11) also discusses the issue, favoring a date "in or just before 1490" as opposed to the much earlier dates, as does Penny (p. 201) "probably in 1490 or a little earlier". The question has become caught up in the still controversial division of works between Giorgione and the young Titian.

- "Metropolitan Museum of Art timeline". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- Wolf, Norbert (2006). I, Titian. New York and London: Prestel. ISBN 9783791333847.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rossetti, William Michael (1911). "Titian". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rossetti, William Michael (1911). "Titian". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Fossi, Gloria, Italian Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture from the Origins to the Present Day, p. 194. Giunti, 2000. ISBN 88-09-01771-4

- The contours in early works may be described as "crisp and clear", while of his late methods it was said that "he painted more with his fingers than his brushes." Dunkerton, Jill, et al., Dürer to Veronese: Sixteenth-Century Painting in the National Gallery, pp. 281–286. Yale University, National Gallery Publications, 1999. ISBN 0-300-07220-1

- Cecil Gould, The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, p. 265, London, 1975, ISBN 0-947645-22-5

- "When Was Titian Born?". Lafrusta.homestead.com. 4 November 2002. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- Hale, 5-6; also see references above

- Durant, Will (1953). The Renaissance. The Story of Civilization. 5. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 667.

- David Jaffé (ed), Titian, The National Gallery Company/Yale, p. 11, London 2003, ISBN 1-85709-903-6

- Jaffé No. 1, pp. 74–75 image

- "Portrait of Gerolamo (?) Barbarigo, about 1510, Titian". National Gallery. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Olga Mataev. "Ecce Homo". Abcgallery.com. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- Charles Hope, in Jaffé, pp. 11–14

- "New findings in Titian's Fresco technique at the Scuola del Santo in Padua", The Art Bulletin, March 1999, Volume LXXXI Number 1, Author Sergio Rossetti Morosini

- explained here

- Charles Hope in Jaffé, p. 14

- Charles Hope, in Jaffé, p. 15

- Charles Hope in Jaffé, pp. 16–17

- Charles Hope, in Jaffé, p. 17 Engraving of the painting

- Jaffé, pp. 100–111

-

Louis Gillet (1913). "Titian". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

Louis Gillet (1913). "Titian". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 30 January 2011. - "Titian", The Catholic Encyclopedia

- R. F. Heath, Life of Titian, p. 5.

- Penny, 204

- Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas, 1996, p. 402, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid, ISBN 84-87317-53-7

- Penny, 249–50

- Giles Robertson, in: Jane Martineau (ed), The Genius of Venice, 1500-1600, pp. 231–3, 1983, Royal Academy of Arts, London

- Robertson, pp. 229–230

- "Titian Madonna and Child sells for record $16.9m". BBC News Online. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- "Art and the Bible". Artbible.info. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- Kennedy, Ian (2006). Titian. Taschen. p. 95. ISBN 9783822849125.

- Hale, 722-723

- Schmidt, Suzanne Karr. "Printed Bodies and the Materiality of Early Modern Prints," Art in Print Vol. 1 No. 1 (May–June 2011), p. 26.

- Landau, 304–305, and in catalogue entries following. Much more detailed consideration is given at various points in: David Landau & Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- Jill Dunkerton and Marika Spring, with contributions from Rachel Billinge, Kamilla Kalinina, Rachel Morrison, Gabriella Macaro, David Peggie and Ashok Roy, Titian’s Painting Technique to c.1540, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, volume 34, 2013, pp. 4–31. Catalog I and II.

- Pigments used by Titian, ColourLex

- Hale, 215

- Hale, 249

- Hale, 486

- Rossetti 1911.

- [Le maraviglie dell'arte: ovvero Le vite degli illustri pittori], Volume 1, by Carlo Ridolfi, Giuseppe Vedova, page 288.

- Ridolfi and Vedova, page 289.

- Boni, Filippo de' (1852). Biografia degli Artisti, Emporeo biografico metodico, volume unico. Venice (1840); Googlebooks: Co' Tipi di Gondolieri. p. 703.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Mark Hudson, Titian: The Last Days, Walker and Company, NY, 2000, pp. 10–11.

- Carrell, Severin (2 February 2009). "Titian's Diana and Actaeon saved for the nation". The Guardian.

- "Yahoo.com".

References

- Cole, Bruce, Titian and Venetian Painting, 1450-1590, Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado, 1999, ISBN 0-8133-9043-5

- Gould, Cecil, The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, London, 1975, ISBN 0-947645-22-5

- Hale, Sheila, Titian: His Life, HarperCollins, New York, NY, 2012, ISBN 978-0-00717582-6

- Jaffé, David (ed.), Titian, The National Gallery Company/Yale, London, 2003, ISBN 1-85709-903-6

- Landau, David, in Jane Martineau and Charles Hope (eds.), The Genius of Venice, 1500–1600, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1983, ISBN 0810909855, ISBN 0297783238

- Loh, Maria H., Titian's Touch: Art, Magic and Philosophy, Reakton Books, London, 2019, ISBN 978-1789140828, ISBN 178914082X

- Penny, Nicholas, National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings, Volume II, Venice 1540–1600, 2008, National Gallery Publications Ltd, ISBN 1-85709-913-3

- Ridolfi, Carlo (1594–1658); The Life of Titian, translated by Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter E. Bondanella, Penn State Press, 1996, ISBN 0-271-01627-2, ISBN 978-0-271-01627-6 Google Books

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Titian |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Titian. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Titian. |

- Titian at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- 139 paintings by or after Titian at the Art UK site

- A closer Look at the Madonna of the Rabbit multimedia feature, Musée du Louvre official site (English version)

- The Titian Foundation Images of 168 paintings by the artist.

- Titian's paintings

- Tiziano Vecellio at Web Gallery of Art

- Christies' sale blurb for the recently restored 'Mother and Child'

- Bell, Malcolm The early work of Titian, at Internet Archive

- Titian at Panopticon Virtual Art Gallery

- How to Paint Like Titian James Fenton essay on Titian from The New York Review of Books

- Tiziano Vecellio - one of the greatest artists of all time

- Interactive high resolution scientific imagery of Titian's Portrait of a Woman with a Mirror from the C2RMF

- Titian: general resources, his paintings, and pigments used, ColourLex

- Teresa Lignelli, “Archbishop Filippo Archinto by Titian (cat. 204),” in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works, a Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication