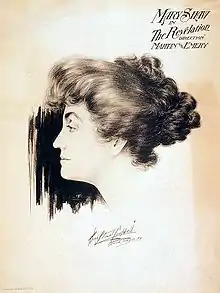

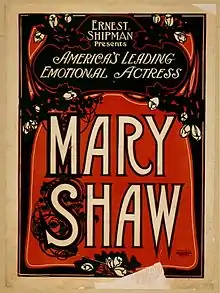

Mary Shaw (actress)

Mary G. Shaw (1854–May 18, 1929) was an American suffragette, early feminist, playwright, and actress.

Shaw was involved in the women's movement since the early 1890s, and in 1892 she became a member of the Professional Women's League. She played many controversial roles in her career as an actress, and was involved in some of the most controversial plays of her time such as Henrik Ibsen's Ghosts and Hedda Gabler, George Bernard Shaw's (no relation) Mrs. Warren's Profession and many female suffrage plays.

Shaw, along with actress Jessie Bonstelle, designed the Woman's National Theatre in the early twentieth century.[1]

Shaw married Henry Leach in 1879 and he died two and a half years later.[2] She then married musician Gustave Krollman who also died shortly thereafter.[3] She was the mother of Broadway actor Arthur Shaw (1881–1946). Shaw suffered and would die from heart disease. The Cradle Song was her last appearance on stage as a result of the illness.[4]

Actress

Professional Women's League

One of the major factors of Mary Shaw's success as a speaker and suffragist was due to her association with clubs that were used to gain wider cultural and social acceptance of different professions. Actresses formed clubs to develop organizational and speaking skills, which later helped Mary Shaw in her work for the women's suffrage movement. The most important actresses’ club was the Professional Women's League, which was founded by actresses and wives of theatrical managers. The charter designated women to join that "engaged in dramatic, musical, and literary pursuits with the purpose of rendering them helpful to each other."[5] The League descended from a larger club, Sorosis, which did not support this new and growing club. There was much disagreement and blackballing of actresses as a result of this split. A main component of the League were the lessons given to young actresses that taught them how to create their own costumes in dressmaking classes.[5]

Although Mary Shaw was a member of the club and a suffragist herself, the League was not only for women's suffrage because there were also others who were against the movement. Mary Shaw strongly believed that suffrage was the only logical opinion to have. She said "the woman who will not think for herself… does harm to her own nature."[2]

Mary Shaw decided, after the disapproval of the suffragist movement, to run for president of the League in 1913. She lost by three votes, and many women vowed to never set foot in the club again.[5] In less than a month the Professional Women's League had split in half. Mary Shaw and many of her supporters left to form the Gamut Club, which had a more relaxed atmosphere and welcomed women of all different kinds of professions.

On the Stage

An early edition of The Theatre Magazine claimed that "to see Mary Shaw act...is inevitably to feel an interest in the woman behind the actress."[2] Mary Shaw was onstage consistently throughout her life. She was particularly drawn to the work of popular playwrights Henrik Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw, but she did not limit herself to their work. Though she starred in shows with varying production values, Shaw was picky when it came to the moral implications of her art. She often chose her roles with a feminist mindset as most plays at the time were created by men and did not portray women correctly.[6] When offered a part in Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch, she turned it down claiming that "it teaches contentment with and resignation to poverty."[2] Her dedication to acting was inspiring. Even when her mother suddenly passed away on the eve of an opening show, she insisted on performing. Unfortunately, the reviews for the show were less than glowing as she was appropriately distracted. Shaw was often criticized for acting in a very explicit way, namely for wearing excessive makeup as in her more risqué roles.[7] Fortunately, other shows had more success. She originated the title character of G.B. Shaw's Mrs. Warren's Profession and revived the role several times in her life, each time to complimentary reviews. Shaw's role in Mrs. Warren's Profession was very controversial for the undesirable way she acted in a specific scene in the play. It was said by various critics that her character spoke in too much of a low-class tone than what was deemed socially acceptable in performance at that time.[8]

The extremely controversial Ghosts was another career mark role for Shaw, with its first English performances occurring in 1894. The play, which Shaw took on an American tour, received mostly outrage and critical backlash. Despite this response, Shaw successfully produced various plays following the tour.[5]

Playwright

In her lifetime, Shaw wrote and directed several satirical pieces including The Parrot Cage. The play is set within a parrot cage where several archetypal female parrots live. There is the free-souled parrot who wants to be free of the cage and the Philistine, the idealist, the rationalist, the reasoning, and the theological parrots who oppose the desires of the free-souled parrot. A man's voice designates the master who occasionally comes in to tell the parrots how pretty they are and reminds them that "Polly's place is in the cage." By the end of the show, the free parrot escapes and instructs the other parrots to "Follow me!" Through this clever satire, Shaw urges women to be free of their domestic cages.[9]

Suffragist

Mary Shaw believed that each gender needed to understand the other and "she wished to see more women successfully entering the professional arena in direct competition with men" to create platonic relationships.[2] Shaw advocated for nonsexual relationships between men and women, and in this, equality would be born. Before men could get on board with suffrage, Shaw needed women to see this "new sense of responsibility, for there were many women to whom the concept of political equality was, in itself, ‘an enlightenment’".[2]

The Gamut Club

In 1917, Mary Shaw revived Ghosts "in order to raise money for one of her non-theatrical projects, The Gamut Club".[2] The Gamut Club was for women from every walk of life to get together and live and talk and experience the world with one another. Shaw created The Gamut Club with ambition "to provide professional women from diverse fields with the equivalent in comfortable surroundings to those which professional men had enjoyed for decades".[2] She was inspired while on tour in 1908, when she was extended honorary membership to a men's club in Los Angeles called the Gamut Club. Shaw aimed to keep membership dues in her own club low enough to accommodate professional women of modest means. She was elected President of the club and continued to be re-elected annually until her death. Though originally housed in a temporary space, her dreamed of building a facility like the men's club: a residential clubhouse with a stage, reading rooms, and even a pool would come true.[2]

The club made many efforts during the war such as offering services as a canteen and performing small acts for servicemen. It was the first of women's clubs to do so. There was a great deal of protesting done as a result of the oncoming World War I. One example is the thousands of activists whom Shaw assembled for a silent "Peace Parade" that took place in New York City protesting the war.[5]

References

- Chinoy, Helen (2006). Women in American Theatre. New York: Theatre Communications Group, Inc. p. 30. ISBN 1-55936-263-4.

- Irving, John D. (1982). Mary Shaw, Actress, Suffragist, Activist (1854–1929). New York: Arno Press. ISBN 978-0-405-14089-1.

- T. Allston, Brown (1969). History of the American Stage; Containing Biographical Sketches of Nearly Every Member of the Profession That Has Appeared on the American Stage, from 1733 to 1870. New York: Blom.

- "Mary Shaw Dies; Noted Isben Player". The New York Times. May 29, 1929. ProQuest 104982006.

- Auster, Albert (1984). Actresses and Suffragists: Women in the American Theatre. New York: Praeger. pp. 1890–1920.

- Chinoy, Helen Krich; Jenkins, Linda Walsh (2006). Women in American Theatre. New York: Theatre Communications Group.

- Johnson, Katie N. (2009). Sisters in Sin: Brothel Drama in America, 1900–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge U.

- Johnson, Katie N. (2009). Sisters in Sin: Brothel Drama in America, 1900–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge U.

- Shaw, Mary (1987). The Parrot Cage: A Play in One Act from On to Victory; Propaganda Plays of the Woman Suffrage Movement. Northeast University Press. pp. 299–306.

External links

- Mary Shaw at the Internet Broadway Database

- book on Mary Shaw, Google Books

- New York Times ACTRESSES TO HAVE A CLUB.;They Are Displeased, It Is Said, with the P.W.L. Management ...(Thursday May 15, 1913)

- Mary Shaw as a young woman at NY Public Library Billy Rose collection

- Mary Shaw portrait Univ. of Washington Sayre Collection

- Mary Shaw's play, The Parrot Cage