Masao Horiba

Masao Horiba (堀場 雅夫, Horiba Masao, December 1, 1924 – July 14, 2015) was a Japanese businessman. In 1945, he founded Horiba Radio Laboratory, now Horiba Ltd., a manufacturer of advanced analytical and measurement technology. Masao Horiba received several awards from the Japanese government including a national Blue Ribbon Medal, and was the first non-American to receive the Pittcon Heritage Award.[1]

Masao Horiba | |

|---|---|

堀場 雅夫 | |

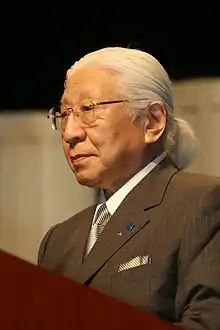

Masao Horiba in 2006 | |

| Born | December 1, 1924 Shimogyō-ku, Kyoto, Japan |

| Died | July 14, 2015 (aged 90) |

| Nationality | Japan |

| Alma mater | Kyoto University |

| Awards | Pittcon Heritage Award |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry, technology |

| Institutions | Horiba, Ltd. |

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Early life and education

Masao Horiba was born on December 1, 1924,[2] in Shimogyō-ku, Kyoto, Japan. He was the second son of Shinkichi Horiba, a chemistry professor at Kyoto Imperial University, and his wife Mikiko.[3] As a child, Horiba suffered from juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.[2][4] He attended Kyoto Teachers' School's Elementary School and Konan Junior High and Senior High Schools in Kobe, Japan.[3]

Originally interested in mathematics and astronomy, Horiba was introduced to nuclear physics by one of his high school teachers[5] at the Konan Boys' High School.[2] He received a B.S. in physics,[2] and hoped to study nuclear physics with Bunsaku Arakatsu at Kyoto University. However, further study in nuclear physics was not possible in post-war Japan. The American authorities had banned such study, and instruments and testing devices had been removed or destroyed.[3][5]

Establishing a company

Horiba, who was in his second year at Kyoto University, left the university in 1945 to start his own business, Horiba Radio Laboratory (HRL). In addition to producing electronic parts and repairing electronic instruments, they reconditioned batteries.[1] The power distribution system after the war was unreliable, so there was a strong demand for storage batteries for electric lights that could be used in the case of blackouts. Horiba acquired discarded storage batteries and selenium rectifiers which the company Nihon Denchi had produced for wartime use.[5] Sales of Horiba's reconditioned "Teidento" batteries were a profitable source of income for the Horiba company.[1]

One of the instruments that Horiba produced and repaired was an electric-pulse oscillator, used in brain surgery. When an oscillator stopped working in the middle of an operation, Masao Horiba was called upon to make emergency repairs. He got the instrument working so the surgeons could finish the operation, and then took the instrument home to examine it in more detail. Examination of the components showed that an electrolytic capacitor had failed. When it proved difficult to buy low-cost reliable replacements, Horiba started producing electrolytic capacitors. By integrating quality control into the production process, he was able to produce high-quality products. He partnered with an investor but their plans to build a capacitor plant fell through when the Korean war caused Japanese metal prices to rise.[1]

One of the instruments needed for the capacitor manufacturing processes was the pH meter. Imported pH meters tended to be unreliable, possibly because of Japan's hot and humid climate.[2] They were also expensive. Rather than buy imported pH meters, Horiba had built his own pH meters for capacitor testing.[1] He saw a potential market for reliable, low-cost pH meters in Japan's food and chemical industries, and partnered with Kitahama Works, a major scientific instruments company, to sell them. The pH meters were sold to fertilizer plants throughout Japan to monitor pH levels in the production of ammonium sulfate fertilizer for use in rice production.[5] In 1953, "Horiba Radio Laboratory" was renamed "Horiba Ltd."[1]

Technology development

Masao Horiba continued to look for new opportunities for his company. After investigating gas chromatography, Horiba decided instead to develop instruments for infrared analysis. The Horiba company already had some experience in creating synthetic single crystals for use in infrared instruments. With support from the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry, the first Horiba IR infrared-based gas analyzer was sold in 1958, followed by a model for industrial use in 1962.[1]

Masao Horiba visited the United States in 1958 as part of a study tour for delegates approved by the Japan Productivity Center. He was particularly interested in seeing the National Bureau of Standards.[5] During this trip, he also met representatives of Hitachi, Ltd., beginning a relationship with the Hitachi company.[3][2]

The next major product developed at the Horiba company resulted from the work of Masahiro Oura, a young researcher who saw the potential for an auto-emissions measurement instrument. Masao Horiba supported the project once he learned that Oura had orders from several major automobile manufacturers. The company's MEXA-1 air emissions analyzer, which came out in 1964, was the first in a series of analysis devices of increasing sensitivity. The MEXA-1 became important for the company's international expansion. In 1970, Horiba partnered with (and later acquired) Olson Laboratories, expanding into Europe and the UK.[1] In 1975, a MEXA analyzer was sold to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Horiba model MEXA-200 infrared CO analyzer was adopted by the EPA for the regulation auto emissions.[6] MEXA systems were bought by Mercedes-Benz in Germany, and Renault in France.[1]

Writing and lecturing

In 1978, at the age of 53, Horiba became chairman of the company, passing the role of president to Masahiro Oura. In 1992, Oura was succeeded by Atsushi Horiba, Horiba's son.[1]

Horiba actively promoted venture capital investment, particularly in the Kyoto area, as an adviser to the Advanced Software Technology and Mechatronics Research Institute of Kyoto (ASTEM), one of the largest start-up incubator organizations in Japan. He was a representative of the Japan Association of New Business Incubation Organization (JANBO) which was established in 1999 as a nationwide network for the support of new businesses in Japan. He served as the chairman of the Innovation Initiative Network Japan (Innovation-Net) established in 2009 to revitalize regional economies by promoting collaboration between industries and universities.[7] Masao Horiba was also a founder and past president of the Association of Asian Business Incubation (AABI) which encourages support of initiatives throughout Asia, not just in Japan.[1]

Horiba wrote and lectured on business and management. He published several books, including Keiei Kokoroe-cho (The Management Handbook) and Iyanara Yamero (Joy and Fun).[1] Horiba promoted the corporate philosophy of Omoshiro Okashiku or Live Merrily and Cheerfully.[3] He advocated that work should be meaningful and fulfilling, and that employees should be encouraged to be creative, take risks, and question accepted practices. Employers are encouraged to "let the nail stand out", a significant departure from the Japanese adage that "The nail that stands out gets beaten down."[1]

Awards

The Masao Horiba Awards were established through the Horiba company to recognize young scientists in analytical science, outside the group companies, "who are devoting themselves to research and development of innovative technology in analysis and measurement."[8]

In 1982, Horiba received the Blue Ribbon Medal of Honor from the Government of Japan, awarded to individuals who have made significant achievements in public service or public welfare.

In recognition of his entrepreneurship and contributions to scientific instrumentation and to society, Masao Horiba was awarded the Pittcon Heritage Award in 2006, at the Pittsburgh Conference on Analytical Chemistry and Applied Spectroscopy and the Chemical Heritage Foundation.[9] The award is given to those "whose entrepreneurial careers shaped the instrumentation community, inspired achievement, promoted public understanding of the modern instrumentation sciences, and highlighted the role of analytical chemistry in world economies." [10] Masao Horiba is the first non-American to receive the Pittcon Award.[11]

On July 14, 2015, Horiba died in his sleep at the age of 90.[12][13]

References

- Ulrych, Richard (2004). "A Japanese instrument pioneer". Chemical Heritage Magazine. 22 (1): 12–13, 35–37. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- Center for Oral History. "Masao Horiba". Science History Institute.

- "Masao Horiba". Center for Research in Business, Kwansei Gakuin University. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- Brock, David C. (November 20, 2004). Masao Horiba, Transcript of Interviews Conducted by David C. Brock at HORIBA, Ltd. Kyoto, Japan on 19 and 20 November 2004 (PDF). Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Foundation.

- Horiba, Masao (February 2011). "Speech In Honouring the Masao Horiba Award Winners" (PDF). Readout (English Edition). Horiba Technical Reports (14). Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- "Horiba Mexa-200". Science History Institute. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- "Winner of the METI Minister's Award under the Third Commendation Program for Supporting Regional Industries (Innovation-Net Award 2014)". Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- "Masao Horiba Awards". Horiba. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- "Pittcon Heritage Award". Science History Institute. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- Patel-Predd, Prachi (March 12, 2006). "Masao Horiba gets Pittcon Heritage Award". LC GC Chromatography Online. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- "The First Non-American to Receive the Prize and Be Inducted into the Hall of Fame HORIBA's Founder, Masao Horiba Receives Analytical Chemistry Prize". Horiba Ltd. March 14, 2006. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- "Notice for a Death: Dr. Masao Horiba, Founder and Supreme Counsel of HORIBA, Ltd". HORIBA Explore the Future. HORIBA, Ltd. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Takeda, Shinobu (July 17, 2015). "Revered postwar entrepreneur just wanted to have fun". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.