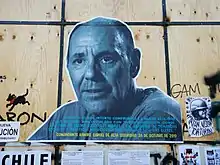

Mauricio Hernández Norambuena

Mauricio Hernández Norambuena (born 23 April 1958) is a former guerrilla fighter and commander of the political-military organization Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front (Frente Patriótico Manuel Rodríguez, FPMR) where he performed some of the main military and logistical functions within the group, thus becoming one of its main leaders. During his stay at the FPMR, he acquired the nickname "Commander Ramiro" (Comandante Ramiro), with which he is still widely known today.

Mauricio Hernández Norambuena | |

|---|---|

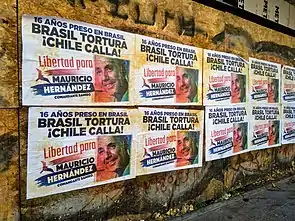

Poster with the image of Mauricio Hernández Norambuena, put outside of the Centro Cultural Gabriela Mistral during the 2019–20 Chilean Social Outbreak. | |

| Nickname(s) | Commander Ramiro |

| Born | April 23, 1958 Valparaíso, Chile |

| Allegiance | |

| Website | www.mauriciohernandeznorambuena.cl (in Spanish) |

Both the FPMR and Mauricio Hernández Norambuena were declared to be terrorists by the United States Department of State from 1997 until 1999.[1][2]

Biography

Born into a socialist family, he was born to marine biologist Moisés Hernández and lawyer Laura Norambuena.[3] With all of his brothers being militants of the Communist Party of Chile, at the end of the 1970s he began to participate in street protests known as the National Protest Days (in Spanish, Jornadas de Protesta Nacional).

Graduated as a professor of Physical Education at the University of Chile in Valparaíso, he joined the Communist Youth of Chile, and, in 1983, after being promoted by the FPMR militant Cecilia Magni (Commander Tamara), he enlisted in the ranks of the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front.[4] With her, he traveled to Cuba to receive paramilitary training.[5]

A direct participant in the most risky actions of the FPMR, in September 1986, he won the trust of Raúl Pellegrin's leadership by organizing one of the four groups of riflemen in the assassination attempt against Augusto Pinochet. His preparation and his intense career as his combatant led him to become one of the leaders of the organization.[6]

He was considered one of the "tough" commanders; Although he had litle political preparation, he had support within the FPMR for having emerged from the lower class. Mauricio Hernández is often credited as the intellectual leader of the murder of Senator Jaime Guzmán, carried out in 1991, which was a time where the FPMR was arguing between either continuing armed operations or tactical withdrawal.

On August 5, 1993, he was arrested by the Investigations Police of Chile at a gas station in Curanilahue along with his bodyguard, Agdalín Valenzuela, who would be executed two years later by his fellow FPMR militants after being accused of having turned him in.[7]

Hernández was sentenced to double life imprisonment for his involvement in the murder of Senator Guzmán He was also convicted of infraction of the arms law, illicit association, terrorist conduct, falsification of public instruments and impersonation. He was also prosecuted for his participation in 1986 as a rifleman in the attack against Pinochet and in 1990 against the former commander in chief of the Chilean Air Force, Gustavo Leigh. He also recognized his actions in the kidnapping of Carlos Carreño (colonel of the army) and Cristián Edwards (son of the owner of the pro-Pinochet Chilean newspaper El Mercurio), in an explosive attack at the National Stadium and in countless bank robberies.

After just over three years in prison, on December 30, 1996, Mauricio Hernández Norambuena, Ricardo Palma Salamanca, Pablo Muñoz Hoffman and Patricio Ortiz Montenegro were "rescued" in an armored basket dangled from a helicopter above the High Security Prison of Santiago where they were serving time.[8] This operation would be known as the Flight of Justice (in Spanish, Vuelo de Justicia).[9]

Investigations estimate that immediately after the escape he traveled to Cuba. After disagreements with the government of Fidel Castro, in 1998 he left Cuba. He traveled to Nicaragua, El Salvador and, later on, to Colombia. There he joined the ELN and the FARC, and, since they respected his military rank, he trained and came to have under his command a column of the guerrillas from that country. Later on, he migrated to Uruguay, Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil, settling definitively in the city of São Paulo.

On February 2, 2002, Mauricio Hernández was arrested along with six other people in the town of Serra Negra after accused of the kidnapping and subsequent captivity of the Brazilian businessman Washington Olivetto in 2001. He was convicted and held in the Federal Penitentiary of Mossoró, in the Maximum Security Penitentiary of Catanduva and the Maximum Security Penitentiary of Avaré in Brazil, where he served part of the 30-year sentence that he received from the Brazilian justice.[10] A few days later, he gave an interview to the newspaper Estado de Sao Paulo in which he harshly criticized the conditions in which he was detained. During this entire period he was subjected to a prison regime called "differential disciplinary", which implied being confined in a 2x3 meter cell for 23 hours a day, with one hour spent in the yard alone, in addition to being locked up 24 hours a day on Saturday and Sunday.[11]

He has been singled out by journalists, scholars and members of the Brazilian public security apparatuses as the intellectual mentor of various terrorist attacks carried in 2006 and the one who introduced terrorist practices, such as bomb attacks, bus fires and political assassinations, in Brazilian criminal groups.[12]

On August 19, 2019, he was transferred from the Maximum Security Penitentiary of Avaré to the Federal Police of Brazil jail in São Paulo, due to the decision of the President of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro to accept the extradition request made by the Chilean justice, arriving in Chile the next day.[13][14]

Finally, on September 2, 2019, Judge Mario Carroza sentenced him to two sentences of 15 years in prison, minus the 1,256 days that he spent in detention for the original sentence in Chile. Therefore, he must serve more than 26 years in prison.[15]

Mauricio Hernández's defense filed a complaint against the fourth chamber of the appeals court, which sought to subtract from his sentence the time he was imprisoned in Brazil for the kidnapping of businessman Washington Olivetto, however, on May 20 of 2020, the Chilean Supreme Court denied said appeal, ratifying the 26-year sentence imposed by the courts until the year 2046.[16]

In popular culture

In the 2012 mini-series To Love and to Die in Chile (in Spanish, Amar y Morir en Chile), he is played by Chilean actor Íñigo Urrutia.[17]

The chilean punk rock band Curasbun wrote a song about him in their 2016 album Inmortales (Immortals), simply titled "Ramiro".[18]

In the 2020 film To Kill Pinochet (in Spanish, Matar a Pinochet), he is played by Chilean actor Cristián Carvajal.[19]

References

- Patterns of Global Terrorism 2002. Government Printing Office. 2003. p. 72. ISBN 9780160679032.

- "Foreign Terrorist Organizations". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- "¿Mauricio?". Libertad a Ramiro (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- Quiroz, Nelson (2019-08-20). "Back in Prison in Chile: "Comandante Ramiro"". Chile Today. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- "O material jornalístico produzido pelo Estadão é protegido por lei. As regras têm como objetivo proteger o investimento feito pelo Estadão na qualidade constante de seu jornalismo". O Estado de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). 2002-05-11. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- Paúl, Fernanda (2019-09-02). "Mauricio Hernández Norambuena, "comandante Ramiro": el exguerrillero protagonista de la "fuga del siglo" en Chile que condenaron a 30 años de prisión". BBC News (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- Siredey E., Francisco (2015-10-10). "El misterio del "hombre clave" de la transición". La Tercera (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- "Chilean Leftists Flee Jail in a Helicopter". The New York Times. 1997-01-01. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- "Operación Vuelo de Justicia: 24 años del formidable rescate de los frentistas de Cárcel de Alta Seguridad". Resumen (in Spanish). 2020-12-20. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- "Chilean Leftist Is Held in Brazil Kidnapping". The New York Times. 2002-02-05. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- "Ex militante del FPMR se refiere a la baja en la condena del "Comandante Ramiro"". CNN Chile (in Spanish). 2016-12-14. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- Couthino, Leonardo (2019-02-19). "The Evolution of the Most Lethal Criminal Organization in Brazil—the PCC". National Defense University. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- Mônica, Bergamo (2019-09-19). "Bolsonaro extraditará sequestrador de Washington Olivetto para o Chile". Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2019-11-22. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- "Former Guerrilla Mauricio Hernandez Norambuena Extradited from Brazil to Chile". AMW English. 2019-08-26. Archived from the original on 2019-10-10. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- "Mauricio Hernández Norambuena estará en la cárcel hasta 2046". Radio Cooperativa (in Spanish). 2019-09-02. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- "Corte Suprema confirma condena de cárcel hasta 2046 para el "comandante Ramiro"". Teletrece (in Spanish). 2020-05-20. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- "Amar y Morir en Chile". Crew United. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- "Curasbun – Inmortales". Discogs. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- Mosciatti, Ezio (2020-11-05). "Matar a Pinochet: "Vamos a seguir penándole a Chile"". Bío-bio Chile (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-01-01.

External links

- Mauricio Hernández Norambuena's website (in Spanish)

Further reading

- Hernández, Mauricio (2016). Un paso al frente: habla el comandante Ramiro del FPMR [A step towards the front: Commander Ramiro from the FPMR speaks up] (in Spanish) ISBN 9789563590562

- Peña, Juan Cristóbal (2007). Los fusileros: crónica secreta de una guerrilla en Chile [The riflemen: The secret chronicle of a Chilean guerrilla] (in Spanish) ISBN 9789569545290

- Palma Salmanca, Ricardo (1997) El gran rescate [The great rescue] (in Spanish) ISBN 9789560011336