Max Roach

Maxwell Lemuel Roach (January 10, 1924 – August 16, 2007) was an American jazz drummer and composer. A pioneer of bebop, he worked in many other styles of music, and is generally considered one of the most important drummers in history.[1][2] He worked with many famous jazz musicians, including Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Abbey Lincoln, Dinah Washington, Charles Mingus, Billy Eckstine, Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, Eric Dolphy, and Booker Little. He was inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1992.[3]

Max Roach | |

|---|---|

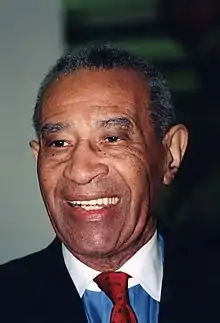

Roach in 2000 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Maxwell Lemuel Roach |

| Born | January 10, 1924 (disputed) Pasquotank County, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | August 16, 2007 (aged 83) New York City, New York |

| Genres | Jazz, bebop |

| Occupation(s) | |

| Instruments | Drums, percussion, piano |

| Years active | 1944–2002 |

| Labels | Capitol, Impulse! |

| Associated acts | |

Roach also co-led a pioneering quintet along with trumpeter Clifford Brown and the percussion ensemble M'Boom. He made numerous musical statements relating to the civil rights movement.

Biography

Early life and career

Max Roach was born to Alphonse and Cressie Roach in the Township of Newland, Pasquotank County, North Carolina, which borders the southern edge of the Great Dismal Swamp. The Township of Newland is sometimes mistaken for Newland Town in Avery County, North Carolina. Although his birth certificate lists his date of birth as January 10, 1924, Roach has been quoted by Phil Schaap, saying that his family believed he was actually born on January 8, 1925.[4]

Roach's family moved to the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, when he was four years old. He grew up in a musical home with his gospel singer mother. He started to play bugle in parades at a young age. At the age of 10, he was already playing drums in some gospel bands.

In 1942, as an 18-year-old recently graduated from Boys High School, he was called to fill in for Sonny Greer with the Duke Ellington Orchestra performing at the Paramount Theater in Manhattan. He starting going to the jazz clubs on 52nd Street and at 78th Street & Broadway for Georgie Jay's Taproom, where he played with schoolmate Cecil Payne.[5] His first professional recording took place in December 1943, backing Coleman Hawkins.[6]

He was one of the first drummers, along with Kenny Clarke, to play in the bebop style. Roach performed in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis. He played on many of Parker's most important records, including the Savoy Records November 1945 session, which marked a turning point in recorded jazz. His early brush work with Powell's trio, especially at fast tempos, has been highly praised.[7]

Roach nurtured an interest in and respect for Afro-Caribbean music and traveled to Haiti in the late 1940s to study with the traditional drummer Ti Roro.[8]

1950s

Roach studied classical percussion at the Manhattan School of Music from 1950 to 1953, working toward a Bachelor of Music degree. The school awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in 1990.

In 1952, Roach co-founded Debut Records with bassist Charles Mingus. The label released a record of a May 15, 1953 concert billed as "the greatest concert ever", which came to be known as Jazz at Massey Hall, featuring Parker, Gillespie, Powell, Mingus, and Roach. Also released on this label was the groundbreaking bass-and-drum free improvisation, Percussion Discussion.[9]

In 1954, Roach and trumpeter Clifford Brown formed a quintet that also featured tenor saxophonist Harold Land, pianist Richie Powell (brother of Bud Powell), and bassist George Morrow. Land left the quintet the following year and was replaced by Sonny Rollins. The group was a prime example of the hard bop style also played by Art Blakey and Horace Silver. Brown and Powell were killed in a car accident on the Pennsylvania Turnpike in June 1956. The first album Roach recorded after their deaths was Max Roach + 4. After Brown and Powell's deaths, Roach continued leading a similarly configured group, with Kenny Dorham (and later Booker Little) on trumpet, George Coleman on tenor, and pianist Ray Bryant. Roach expanded the standard form of hard bop using 3/4 waltz rhythms and modality in 1957 with his album Jazz in 3/4 Time. During this period, Roach recorded a series of other albums for EmArcy Records featuring the brothers Stanley and Tommy Turrentine.[10]

In 1955, he played drums for vocalist Dinah Washington at several live appearances and recordings. He appeared with Washington at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958, which was filmed, and at the 1954 live studio audience recording of Dinah Jams, considered to be one of the best and most overlooked vocal jazz albums of its genre.[11]

1960s–1970s

In 1960 he composed and recorded the album We Insist! (subtitled Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite), with vocals by his then-wife Abbey Lincoln and lyrics by Oscar Brown Jr., after being invited to contribute to commemorations of the hundredth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. In 1962, he recorded the album Money Jungle, a collaboration with Mingus and Duke Ellington. This is generally regarded as one of the finest trio albums ever recorded.[12]

During the 1970s, Roach formed M'Boom, a percussion orchestra. Each member composed for the ensemble and performed on multiple percussion instruments. Personnel included Fred King, Joe Chambers, Warren Smith, Freddie Waits, Roy Brooks, Omar Clay, Ray Mantilla, Francisco Mora, and Eli Fountain.[13]

Long involved in jazz education, in 1972 Roach was recruited to the faculty of the University of Massachusetts Amherst by Chancellor Randolph Bromery.[14] He taught at the university until the mid-1990s.[15]

1980s–1990s

In the early 1980s, Roach began presenting solo concerts, demonstrating that multiple percussion instruments performed by one player could fulfill the demands of solo performance and be entirely satisfying to an audience. He created memorable compositions in these solo concerts, and a solo record was released by the Japanese jazz label Baystate. One of his solo concerts is available on a video, which also includes footage of a recording date for Chattahoochee Red, featuring his working quartet, Odean Pope, Cecil Bridgewater, and Calvin Hill.

Roach also embarked on a series of duet recordings. Departing from the style he was best known for, most of the music on these recordings is free improvisation, created with Cecil Taylor, Anthony Braxton, Archie Shepp, and Abdullah Ibrahim. Roach created duets with other performers, including: a recorded duet with oration of the "I Have a Dream" speech by Martin Luther King Jr.; a duet with video artist Kit Fitzgerald, who improvised video imagery while Roach created the music; a duet with his lifelong friend and associate Gillespie; and a duet concert recording with Mal Waldron.

During the 1980s Roach also wrote music for theater, including plays by Sam Shepard. He was composer and musical director for a festival of Shepard plays, called "ShepardSets", at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club in 1984. The festival included productions of Back Bog Beast Bait, Angel City, and Suicide in B Flat.[16] In 1985, George Ferencz directed "Max Roach Live at La MaMa: A Multimedia Collaboration".[17]

Roach found new contexts for performance, creating unique musical ensembles. One of these groups was "The Double Quartet", featuring his regular performing quartet with the same personnel as above, except Tyrone Brown replaced Hill. This quartet joined "The Uptown String Quartet", led by his daughter Maxine Roach and featuring Diane Monroe, Lesa Terry, and Eileen Folson.

Another ensemble was the "So What Brass Quintet", a group comprising five brass instrumentalists and Roach, with no chordal instrument and no bass player. Much of the performance consisted of drums and horn duets. The ensemble consisted of two trumpets, trombone, French horn, and tuba. Personnel included Cecil Bridgewater, Frank Gordon, Eddie Henderson, Rod McGaha, Steve Turre, Delfeayo Marsalis, Robert Stewart, Tony Underwood, Marshall Sealy, Mark Taylor, and Dennis Jeter.

Not content to expand on the music he was already known for, Roach spent the 1980s and 1990s finding new forms of musical expression and performance. He performed a concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He wrote for and performed with the Walter White gospel choir and the John Motley Singers. He also performed with dance companies, including the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, the Dianne McIntyre Dance Company, and the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. He surprised his fans by performing in a hip hop concert featuring the Fab Five Freddy and the New York Break Dancers. Roach expressed the insight that there was a strong kinship between the work of these young black artists and the art he had pursued all his life.[2]

Though Roach played with many types of ensembles, he always continued to play jazz. He performed with the Beijing Trio, with pianist Jon Jang and erhu player Jeibing Chen. His final recording, Friendship, was with trumpeter Clark Terry. The two were longtime friends and collaborators in duet and quartet. Roach's final performance was at the 50th anniversary celebration of the original Massey Hall concert, with Roach performing solo on the hi-hat.[18]

In 1994, Roach appeared on Rush drummer Neil Peart's Burning For Buddy, performing "The Drum Also Waltzes" Parts 1 and 2 on Volume 1 of the 2-volume tribute album during the 1994 All-Star recording sessions.[19]

Death

In the early 2000s, Roach became less active due to the onset of hydrocephalus-related complications.

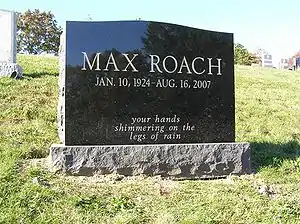

Roach died of complications related to Alzheimer's and dementia in Manhattan in the early morning of August 16, 2007.[20] He was survived by five children: sons Daryl and Raoul, and daughters Maxine, Ayo, and Dara. more than 1,900 people attended his funeral at Riverside Church on August 24, 2007. He was interred at the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx.

In a funeral tribute to Roach, then-Lieutenant Governor of New York David Paterson compared the musician's courage to that of Paul Robeson, Harriet Tubman, and Malcolm X, saying that "No one ever wrote a bad thing about Max Roach's music or his aura until 1960, when he and Charlie Mingus protested the practices of the Newport Jazz Festival."[21]

Personal life

Two children, son Daryl Keith and daughter Maxine, were born from Roach's first marriage with Mildred Roach in 1949. In 1956, he met singer Barbara Jai (Johnson) and fathered another son, Raoul Jordu. During the period 1961–1970, Roach was married to singer Abbey Lincoln, who had performed on several of his albums. In 1971, twin daughters, Ayodele Nieyela and Dara Rashida, were born to Roach and his third wife, Janus Adams Roach.

He had four grandchildren: Kyle Maxwell Roach, Kadar Elijah Roach, Maxe Samiko Hinds, and Skye Sophia Sheffield.

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Max Roach among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.[22]

Style

Roach started as a traditional grip player but used matched grip as well as his career progressed.[23]

Roach's most significant innovations came in the 1940s, when he and Kenny Clarke devised a new concept of musical time. By playing the beat-by-beat pulse of standard 4/4 time on the ride cymbal instead of on the thudding bass drum, Roach and Clarke developed a flexible, flowing rhythmic pattern that allowed soloists to play freely. This also created space for the drummer to insert dramatic accents on the snare drum, crash cymbal, and other components of the trap set.

By matching his rhythmic attack with a tune's melody, Roach brought a newfound subtlety of expression to the drums. He often shifted the dynamic emphasis from one part of his drum kit to another within a single phrase, creating a sense of tonal color and rhythmic surprise.[1] Roach said of the drummer's unique positioning, "In no other society do they have one person play with all four limbs."[24]

While this is common today, when Clarke and Roach introduced the concept in the 1940s it was revolutionary. "When Max Roach's first records with Charlie Parker were released by Savoy in 1945", jazz historian Burt Korall wrote in the Oxford Companion to Jazz, "drummers experienced awe and puzzlement and even fear." One of those drummers, Stan Levey, summed up Roach's importance: "I came to realize that, because of him, drumming no longer was just time, it was music."[1]

In 1966, with his album Drums Unlimited (which includes several tracks that are entirely drum solos) he demonstrated that drums can be a solo instrument able to play theme, variations, and rhythmically cohesive phrases. Roach described his approach to music as "the creation of organized sound."[13] The track "The Drum Also Waltzes" was often quoted by John Bonham in his Moby Dick drum solo and revisited by other drummers, including Neil Peart and Steve Smith.[25][26] Bill Bruford performed a cover of the track on the 1985 album Flags.

Honors

Roach was given a MacArthur Genius Grant in 1988 and cited as a Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France in 1989.[27] He was twice awarded the French Grand Prix du Disque, was elected to the International Percussive Art Society's Hall of Fame and the DownBeat Hall of Fame, and was awarded Harvard Jazz Master. He was celebrated by Aaron Davis Hall and was given eight honorary doctorate degrees, including degrees awarded by Medgar Evers College, CUNY, the University of Bologna, and Columbia University, in addition to his alma mater, the Manhattan School of Music.[28]

In 1986, the London borough of Lambeth named a park in Brixton after Roach.[29][30] Roach was able to officially open the park when he visited London in March of that year by invitation from the Greater London Council.[31] During that trip, he performed at a concert at the Royal Albert Hall along with Ghanaian master drummer Ghanaba and others.[32][33]

Roach spent his later years living at the Mill Basin Sunrise assisted living home in Brooklyn, and was honored with a proclamation honoring his musical achievements by Brooklyn borough president Marty Markowitz.[34] Roach was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame in 2009.[35]

Discography

As leader

- 1953 : The Max Roach Quartet featuring Hank Mobley (Debut)

- 1956 : Max Roach + 4 (EmArcy)

- 1957 : Jazz in 3/4 Time (EmArcy)

- 1957 : The Max Roach 4 Plays Charlie Parker (EmArcy)

- 1958 : MAX (Argo)

- 1958 : Max Roach + 4 on the Chicago Scene (Mercury)

- 1958 : Max Roach/Art Blakey (with Art Blakey)

- 1958 : Max Roach + 4 at Newport (EmArcy)

- 1958 : Max Roach with the Boston Percussion Ensemble (EmArcy)

- 1958 : Deeds, Not Words (Riverside) – also released as Conversation

- 1958 : Award-Winning Drummer (Time) – also released as Max Roach

- 1958 : Max Roach/Bud Shank – Sessions with Bud Shank

- 1958 : The Defiant Ones – with Booker Little

- 1959 : The Many Sides of Max (Mercury)

- 1959 : Rich Versus Roach (Mercury) – with Buddy Rich

- 1959 : Quiet as It's Kept (Mercury)

- 1959 : Moon Faced and Starry Eyed (Mercury) – with Abbey Lincoln

- 1959 : Max Roach (Time) with Booker Little

- 1960 : Long as You're Living (Enja) – released 1984

- 1960 : Parisian Sketches (Mercury)

- 1960 : We Insist! (Candid)

- 1961 : Percussion Bitter Sweet (Impulse!) – with Mal Waldron

- 1962 : It's Time (Impulse!) – with Mal Waldron

- 1962 : Speak, Brother, Speak! (Fantasy)

- 1964 : The Max Roach Trio Featuring the Legendary Hasaan (Atlantic) – with Hasaan Ibn Ali

- 1966 : Drums Unlimited (Atlantic)

- 1968 : Members, Don't Git Weary (Atlantic)

- 1971 : Lift Every Voice and Sing (Atlantic) – with the J.C. White Singers

- 1976 : Force: Sweet Mao–Suid Afrika '76 (duo with Archie Shepp)

- 1976 : Nommo (Victor)

- 1977 : Max Roach Quartet Live in Tokyo (Denon)

- 1977 : The Loadstar (Horo)

- 1977 : Max Roach Quartet Live In Amsterdam – It's Time (Baystate)

- 1977 : Solos (Baystate)

- 1977 : Streams of Consciousness (Baystate) – duo with Dollar Brand

- 1978 : Confirmation (Fluid)

- 1978 : Birth and Rebirth – duo with Anthony Braxton (Black Saint)

- 1979 : The Long March – duo with Archie Shepp (Hathut)

- 1979 : Historic Concerts – duo with Cecil Taylor (Black Saint)

- 1979 : One in Two – Two in One – duo with Anthony Braxton (Hathut)

- 1979 : Pictures in a Frame (Soul Note)

- 1980 : Chattahoochee Red (Columbia)

- 1981 : Live at Blues Alley (MVD Visual)

- 1982 : Swish – duo with Connie Crothers (New Artists)

- 1982 : In the Light (Soul Note)

- 1983 : Live at Vielharmonie (Soul Note)

- 1984 : Scott Free (Soul Note)

- 1984 : It's Christmas Again (Soul Note)

- 1984 : Survivors (Soul Note)

- 1985 : Easy Winners (Soul Note)

- 1986 : Bright Moments (Soul Note)

- 1989 : Max + Dizzy: Paris 1989 – duo with Dizzy Gillespie (A&M)

- 1989 : Homage to Charlie Parker (A&M)

- 1991 : To the Max! (Enja)

- 1995 : Max Roach with the New Orchestra of Boston and the So What Brass Quintet (Blue Note Records)

- 1999 : Beijing Trio (Asian Improv)

- 2002 : Friendship – (with Clark Terry) (Columbia)

Compilations

- Alone Together: The Best of the Mercury Years (Verve Records, 1954–60; 1995)

As co–leader

With Clifford Brown

- 1954: Best Coast Jazz (EmArcy Records)

- 1954: Clifford Brown All Stars (EmArcy Records, released 1956)

- 1954: Jam Session (EmArcy Records, 1954) with Maynard Ferguson and Clark Terry

- 1954 : Brown and Roach Incorporated (EmArcy Records)

- 1954 : Daahoud (Mainstream Records, released 1973)

- 1955 : Clifford Brown with Strings (EmArcy Records)

- 1954–55 : Clifford Brown and Max Roach (EmArcy Records)

- 1955 : Study in Brown (EmArcy Records)

- 1954 : More Study in Brown

- 1956 : Clifford Brown and Max Roach at Basin Street (EmArcy Records)

- 1979 : Live at the Bee Hive (Columbia Records)

With M'Boom

- 1973 : Re: Percussion (Strata-East)

- 1979 : M'Boom (Columbia Records)

- 1984 : Collage (Soul Note)

- 1992 : Live at S.O.B.'s New York (Blue Moon)

As sideman

With Chet Baker

- Witch Doctor (Contemporary, 1953 [1985])

With Don Byas

- Savoy Jam Party (1946)

With Jimmy Cleveland

- Introducing Jimmy Cleveland and His All Stars (EmArcy, 1955)

With Al Cohn

- Al Cohn's Tones (Savoy, 1953 [1956])

With Miles Davis

- Birth of the Cool (Capitol, 1949)

- Conception (Prestige, 1951)

With John Dennis

- New Piano Expressions (1955)

With Kenny Dorham

- Jazz Contrasts (Riverside, 1957)

With Billy Eckstine

- The Metronome All Stars (1953)

With Duke Ellington

- Paris Blues (United Artists, 1961)

- Money Jungle (United Artists, 1962) – with Charles Mingus

With Maynard Ferguson

- Jam Session featuring Maynard Ferguson (EmArcy, 1954)

With Stan Getz

- Opus BeBop (1946)

- Stan Getz and the Cool Sounds (Verve 1953 55, [1957])

With Dizzy Gillespie

- Diz and Getz (Verve, 1953) – with Stan Getz

- The Bop Session (Sonet, 1975) – with Sonny Stitt, John Lewis, Hank Jones and Percy Heath

With Benny Golson

- The Modern Touch (Riverside, 1957)

With Johnny Griffin

- Introducing Johnny Griffin (Blue Note, 1956)

With Slide Hampton

- Drum Suite (Epic, 1962)

With Coleman Hawkins

- Rainbow Mist (Delmark, 1944 [1992]) compilation of Apollo recordings

- Coleman Hawkins and His All Stars (1944)

- Body and Soul (1946)

With Joe Holiday

- Mambo Jazz (1953)

With J.J. Johnson

- Mad Be Bop (1946)

- First Place (Columbia, 1957)

With Thad Jones

- The Magnificent Thad Jones (Blue Note, 1956)

With Abbey Lincoln

- That's Him! (Riverside, 1957)

- Straight Ahead (Riverside, 1961)

With Booker Little

- Out Front (Candid, 1961)

With Howard McGhee

- The McGhee–Navarro Sextet (1950)

With Gil Mellé

- Gil Mellé Quintet/Sextet (Blue Note, 1953)

With Charles Mingus

- Mingus at the Bohemia (Debut, 1955); "Percussion Discussion" only

- The Charles Mingus Quintet & Max Roach (Debut, 1955)

With Thelonious Monk

- Genius of Modern Music: Volume 2 (Blue Note, 1952)

- Brilliant Corners (Riverside, 1956)

With Herbie Nichols

- Herbie Nichols Trio (Blue Note, 1955)

With Charlie Parker

- Town Hall, New York, June 22, 1945 (1945) – with Dizzy Gillespie

- The Complete Savoy Studio Recordings (1945–48)

- Lullaby in Rhythm (1947)

- Charlie Parker's Savoy and Dial sessions/Complete Charlie Parker on Dial/Charlie Parker on Dial (Dial, 1945–48)

- The Band that Never Was (1948)

- Bird on 52nd Street (1948)

- Bird at the Roost (1948)

- Charlie Parker Complete Sessions on Verve (Verve, 1949–53)

- Charlie Parker in France (1949)

- Live at Rockland Palace (1952)

- Yardbird: DC–53 (1953)

- Big Band (Clef, 1954)

With Oscar Pettiford

- Oscar Pettiford Sextet (Vogue, 1954)

With Bud Powell

- The Bud Powell Trip (1947)

- The Amazing Bud Powell (Blue Note, 1951)

With Sonny Rollins

- Work Time (Prestige, 1955)

- Sonny Rollins Plus 4 (Prestige, 1956)

- Tour de Force (Prestige, 1956)

- Rollins Plays for Bird (Prestige, 1956)

- Saxophone Colossus (Prestige, 1956)

- Freedom Suite (Riverside, 1958)

- Stuttgart 1963 Concert (1963)

With George Russell

- New York, N.Y. (1959)

With A. K. Salim

- Pretty for the People (Savoy, 1957)

With Hazel Scott

- Relaxed Piano Moods (1955)

With Sonny Stitt

- Sonny Stitt/Bud Powell/J. J. Johnson (Prestige, 1956)

With Stanley Turrentine

- Stan "The Man" Turrentine (Time, 1960 [1963])

With Tommy Turrentine

- Tommy Turrentine (1960)

With George Wallington

- The George Wallington Trip and Septet (1951)

With Dinah Washington

- Dinah Jams (EmArcy, 1954)

With Randy Weston

- Uhuru Afrika (Roulette, 1960)

With Joe Wilder

- The Music of George Gershwin: I Sing of Thee (1956)

References

- Schudel, Matt (August 16, 2007). "Jazz Musician Max Roach Dies at 83". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- "Legendary Jazz Drummer Max Roach Dies at 83". Billboard. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- "Modern Drummer's Readers Poll Archive, 1979–2014". Modern Drummer. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- MADISON magazine: "Max Roach and James Woods". Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Gitler, Ira (1985). Swing to Bop: An Oral History of the Transition in Jazz in the 1940s. Oxford University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780195364118. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- "Max Roach discography". Jazz Disco. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- Harris, Barry; Weiss, Michael (1994). The Complete Bud Powell on Verve (liner notes, booklet). Verve Records. p. 106.

- Haydon, Geoffrey; Marks, Dennis (1985). "Sit Down and Listen: The Story of Max Roach.". A Celebration of African-American Music. Century Publishing. p. 99.

- "History Explorer > Jazz History Timeline > 1952 - 1961". History Explorer. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- "History of Jazz Part 6: Hard Bop". Jazzitude. April 11, 2007. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- "Joy Spring". Hipjazz. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- "Duke Ellington Money Jungle Blue Note, Recorded 1962". Inkblot (magazine). Archived June 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Max Roach biography". All About Jazz. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- University of Massachusetts, "Randolph W. Bromery, Champion of Diversity, Du Bois and Jazz as UMass Amherst Chancellor, Dead at 87", February 27, 2013.

- Palpini, Kristin (August 17, 2007). "Jazz great, UMass prof Max Roach dies". Amherst Bulletin.

- La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Special Event: 'ShepardSets: A Festival of Sam Shepard Plays' (1984)". Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: 'Max Roach Live at La MaMa: A Multimedia Collaboration' (1985)". Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- "Friendship". All About Jazz. July 25, 2003. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- "The Friday Papers". Beachwood Reporter. August 27, 2007. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- Keepnews, Peter (August 16, 2007). "Max Roach, Master of Modern Jazz, Dies at 83". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Paterson, David (March 13, 2008). "David Paterson Invokes Paul Robeson, Harriet Tubman, Malcolm X in Remembrance of Jazz Legend Max Roach (Eulogy transcript)". Democracy Now. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- Rosen, Jody (25 June 2019). "Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- "Legendary Jazz Drummer Max Roach Dies at 83". Modern Drummer. September 21, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- The Week, August 31, 2007, p. 32.

- "Stanton Moore On John Bonham's Influences". Drum Magazine. April 29, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- "Max Roach: Setting Standards And Raising Bars". Modern Drummer. December 10, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Medals ceremony (video) Ina (French), 1989.

- "University to Award 8 Honorary Degrees at Graduation on May 16". Columbia University Record. April 9, 2001. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- "Max Roach Park". All About Jazz. October 28, 2006. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- "London Borough of Lambeth | Max Roach Park". Lambeth.gov.uk. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- Val Wilmer, letter to The Guardian, September 8, 2007. "It was on the initiative of then Labour councillor Sharon Atkin that Lambeth council named 27 sites in the borough in 1986 to acknowledge contributions by people of African descent.... The opening of the Brixton park coincided with Roach's GLC-sponsored visit to London, happily enabling him to attend the opening in the company of Atkin and his old friend, the drummer Ken Gordon, uncle of Moira Stuart."

- "Akyaaba Addai-Sebo interview", Every Generation Media.

- Jon Lusk, "Kofi Ghanaba: Drummer who pioneered Afro-jazz", The Independent, March 9, 2009.

- "Brooklyn Borough President". Brooklyn-USA. Archived from the original on October 1, 2006. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- "2009 Inductees". North Carolina Music Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

External links

| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |