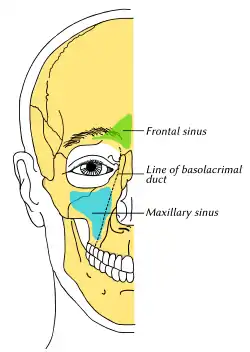

Maxillary sinus

The pyramid-shaped maxillary sinus (or antrum of Highmore) is the largest of the paranasal sinuses, and drains into the middle meatus of the nose through the osteomeatal complex.[1]

| Maxillary sinus | |

|---|---|

Outline of bones of face, showing position of air sinuses. Maxillary sinus is shown in blue. | |

Left maxilla, medial view. Maxillary sinus entry shown in red. | |

| Details | |

| Artery | infraorbital artery, posterior superior alveolar artery |

| Nerve | posterior superior alveolar nerve, middle superior alveolar nerve, anterior superior alveolar nerve, and infraorbital nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | sinus maxilliaris |

| MeSH | D008443 |

| TA98 | A06.1.03.002 A02.1.12.023 |

| TA2 | 780 |

| FMA | 57715 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

It is the largest air sinus in the body. Found in the body of the maxilla, this sinus has three recesses: an alveolar recess pointed inferiorly, bounded by the alveolar process of the maxilla; a zygomatic recess pointed laterally, bounded by the zygomatic bone; and an infraorbital recess pointed superiorly, bounded by the inferior orbital surface of the maxilla. The medial wall is composed primarily of cartilage. The ostia for drainage are located high on the medial wall and open into the semilunar hiatus of the lateral nasal cavity; because of the position of the ostia, gravity cannot drain the maxillary sinus contents when the head is erect (see pathology). The ostium of the maxillary sinus is high up on the medial wall and on average is 2.4 mm in diameter; with a mean volume of about 10 ml.[1][2]

The sinus is lined with mucoperiosteum, with cilia that beat toward the ostia. This membranous lining is also referred to as the Schneiderian membrane, which is histologically a bilaminar membrane with pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelial cells on the internal (or cavernous) side and periosteum on the osseous side. The size of the sinuses varies in different skulls, and even on the two sides of the same skull.[2]

The infraorbital canal usually projects into the cavity as a well-marked ridge extending from the roof to the anterior wall; additional ridges are sometimes seen in the posterior wall of the cavity and are caused by the alveolar canals.

The mucous membranes receive their postganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibres for mucous secretion from the pterygopalatine ganglion. The preganglionic parasympathetic fibres are coming to this ganglion through the greater petrosal nerve (a branch of the facial nerve) and the nerve of the pterygoid canal. The superior alveolar (anterior, middle, and posterior) nerves, branches of the maxillary nerve provide sensory innervation.

Walls

The nasal wall of the maxillary sinus, or base, presents, in the disarticulated bone, a large, irregular aperture, communicating with the nasal cavity. In the articulated skull this aperture is much reduced in size by the following bones:

- the uncinate process of the ethmoid above,

- the ethmoidal process of the inferior nasal concha below,

- the vertical part of the palatine behind,

- and a small part of the lacrimal above and in front.

The sinus communicates through an opening into the semilunar hiatus on the lateral nasal wall.

On the posterior wall are the alveolar canals, transmitting the posterior superior alveolar vessels and nerves to the molar teeth.

The floor is formed by the alveolar process, and, if the sinus is of an average size, is on a level with the floor of the nose; if the sinus is large it reaches below this level. Projecting into the floor of the antrum are several conical processes, corresponding to the roots of the first and second maxillary molar teeth; in some cases the floor can be perforated by the apices of the teeth.

The roof is formed by floor of the orbit. It is traversed by infraorbital nerves and vessels.

Development

It is the first sinus to appear as a shallow groove. At birth it measures about 7*4*4mm. It continues to develops throughout childhood at an annual rate of 2mm vertically and 3mm anteroposteriorly. It reaches its final size in the seventeenth to eighteenth year of life.

Clinical significance

Maxillary sinusitis

Maxillary sinusitis is inflammation of the maxillary sinuses. The symptoms of sinusitis are headache, usually near the involved sinus, and foul-smelling nasal or pharyngeal discharge, possibly with some systemic signs of infection such as fever and weakness. The skin over the involved sinus can be tender, hot, and even reddened due to the inflammatory process in the area. On radiographs, there is opacification (or cloudiness) of the usually translucent sinus due to retained mucus.[3]

Maxillary sinusitis is common due to the close anatomic relation of the frontal sinus, anterior ethmoidal sinus and the maxillary teeth, allowing for easy spread of infection. Differential diagnosis of dental problems needs to be done due to the close proximity to the teeth since the pain from sinusitis can seem to be dentally related.[1] Furthermore, the drainage orifice lies near the roof of the sinus, and so the maxillary sinus does not drain well, and infection develops more easily. The maxillary sinus may drain into the mouth via an abnormal opening, an oroantral fistula, a particular risk after tooth extraction.

Oro-antral communication (OAC)

An OAC is an abnormal physical communication between the maxillary sinus and the mouth. This opening is only present when the structures, that normally separates the mouth and sinus into 2 separate compartments, are lost.[4]

There are many causes of an OAC. The most common reason is following extraction of a posterior maxillary (upper) premolar or molar tooth. Other causes include trauma, pathology (e.g. tumours or cysts), infection or iatrogenic damage during surgery. Iatrogenic damage during dental treatment accounts for nearly half of the incidence of dental-related maxillary sinusitis.[5] There is always a thin layer of mucous membrane (Schneiderian membrane) and usually bone between the roots of the upper back teeth and the floor of the maxillary sinus. However, the bone can vary in thickness in different individuals, ranging from complete absence to 12mm thick.[5] Therefore, in certain individuals the membrane +/- the bony floor of the sinus can be perforated easily, creating an opening into the mouth when a tooth is extracted.[6]

An OAC that is smaller than 2mm can heal spontaneously i.e. closure of the opening.[7] Those that are larger than 2mm have a higher chance of developing into oro-antral fistula (OAF).[7] The passage is only defined as an OAF if it is persistent and lined by epithelium.[7] Epithelialisation happens when an OAC persist for at least 2–3 days and oral epithelial cells proliferate to linethe defect. Large defects (more than 2mm) should be surgically closed as soon as possible to avoid accumulation of food and saliva which could contaminate the maxillary sinus, leading to infection (sinusitis).[7] Various surgical techniques can be employed to manage an OAF but the most common involves pulling and stitching some soft tissue from the gum to cover the opening (i.e. soft tissue flap).[7]

Sinusitis treatment

Traditionally the treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis is usually prescription of a broad-spectrum cephalosporin antibiotic resistant to beta-lactamase, administered for 10 days. Recent studies have found that the cause of chronic sinus infections lies in the nasal mucus, not in the nasal and sinus tissue targeted by standard treatment. This suggests a beneficial effect in treatments that target primarily the underlying and presumably damage-inflicting nasal and sinus membrane inflammation, instead of the secondary bacterial infection that has been the primary target of past treatments for the disease. Also, surgical procedures with chronic sinus infections are now changing with the direct removal of the mucus, which is loaded with toxins from the inflammatory cells, rather than the inflamed tissue during surgery. Leaving the mucus behind might predispose early recurrence of the chronic sinus infection. If any surgery is performed, it is to enlarge the ostia in the lateral walls of the nasal cavity, creating adequate drainage.[3]

Cancer

Carcinoma of the maxillary sinus may invade the palate and cause dental pain. It may also block the nasolacrimal duct. Spread of the tumor into the orbit causes proptosis.[1]

Maxillary sinus cancer that has spread to the brain

Maxillary sinus cancer that has spread to the brain Maxillary sinus cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes

Maxillary sinus cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes

Age

With age, the enlarging maxillary sinus may even begin to surround the roots of the maxillary posterior teeth and extend its margins into the body of the zygomatic bone. If the maxillary posterior teeth are lost, the maxillary sinus may expand even more, thinning the bony floor of the alveolar process so that only a thin shell of bone is present.[3]

History

The maxillary sinus was first discovered and illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci, but the earliest attribution of significance was given to Nathaniel Highmore, the British surgeon and anatomist who described it in detail in his 1651 treatise.[8]

See also

References

- Human Anatomy, Jacobs, Elsevier, 2008, page 209-210

- Bell, G.W., et al. Maxillary sinus disease: diagnosis and treatment, British Dental Journal 210, 113 - 118 (2011) at http://www.nature.com/bdj/journal/v210/n3/full/sj.bdj.2011.47.html

- Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Fehrenbach and Herring, Elsevier, 2012, page 67

- Kiran Kumar Krishanappa, Salian; Eachempati, Prashanti; Kumbargere Nagraj, Sumanth; Shetty, Naresh Yedthare; Moe, Soe; Aggarwal, Himanshi; Mathew, Rebecca J (2018-08-16). "Interventions for treating oro‐antral communications and fistulae due to dental procedures". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (8): CD011784. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011784.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6513579. PMID 30113083.

- Regimantas Simuntis; Ričardas Kubilius; Saulius Vaitkus (2014). "Odontogenic maxillary sinusitis: A review" (PDF). Stomatologija, Baltic Dental and Maxillofacial Journal.

- Franco-Carro, B.; Barona-Dorado, C.; Martínez-González, M.-J.-S.; Rubio-Alonso, L.-J.; Martínez-González, J.-M. (2011-08-01). "Meta-analytic study on the frequency and treatment of oral antral communications". Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 16 (5): e682–687. doi:10.4317/medoral.17058. ISSN 1698-6946. PMID 20711106.

- Khandelwal, Pulkit; Hajira, Neha (January 2017). "Management of Oro-antral Communication and Fistula: Various Surgical Options". World Journal of Plastic Surgery. 6 (1): 3–8. ISSN 2228-7914. PMC 5339603. PMID 28289607.

- Merriam-Webster's Medical Desk Dictionary Revised Ed. 2002, pg 49.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maxillary sinuses. |

- Radiology image: Headneck:17Maxill from Radiology Atlas at SUNY Downstate Medical Center (need to enable Java)

- Cross section image: skull/x-front—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- lesson9 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (latnasalwall3, nasalcavitfrontsec)

- Maxillary Sinus: Normal Anatomy & Variants at http://uwmsk.org/sinusanatomy2/Maxillary-Normal.html

- Cancer in the maxillary sinus, Stanford University at http://cancer.stanford.edu/headneck/sinus/sinus_max.html