Mess of pottage

A mess of pottage is something immediately attractive but of little value taken foolishly and carelessly in exchange for something more distant and perhaps less tangible but immensely more valuable. The phrase alludes to Esau's sale of his birthright for a meal ("mess") of lentil stew ("pottage") in Genesis 25:29–34 and connotes shortsightedness and misplaced priorities.

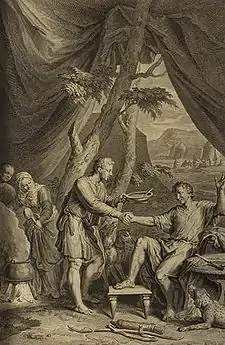

The mess of pottage motif is a common theme in art, appearing for example in Mattia Bortoloni's Esau selling his birthright (1716) and Mattias Stomer's painting of the same title (c. 1640).[1]

Biblical usage

Although this phrase is often used to describe or allude to Esau's bargain, the phrase itself does not appear in the text of any English version of Genesis. Its first attested use,[2] already associated with Esau's bargain, is in the English summary of one of John Capgrave's sermons, c. 1452, "[Jacob] supplanted his broþir, bying his fader blessing for a mese of potage."[3] In the sixteenth century it continues its association with Esau, appearing in Bonde's Pylgrimage of Perfection (1526) and in the English versions of two influential works by Erasmus, the Enchiridion (1533)[4] and the Paraphrase upon the New Testament (1548):[5] "th'enherytaunce of the elder brother solde for a messe of potage". It can be found here and there throughout the sixteenth century, e.g. in Johan Carion's Thre bokes of cronicles (1550)[6] and at least three times in Roger Edgeworth's collected sermons (1557).[7] Within the tradition of English Biblical translations, it appears first in the summary at the beginning of chapter 25 of the Book of Genesis in the so-called Matthew Bible of 1537 (in this section otherwise a reprint of the Pentateuch translation of William Tyndale), "Esau selleth his byrthright for a messe of potage";[8] thence in the 1539 Great Bible and in the Geneva Bible published by English Protestants in Geneva in 1560.[9] According to the OED, Coverdale (1535) "does not use the phrase, either in the text or the chapter heading..., but he has it in 1 Chronicles 16:3 and Proverbs 15:7."[10] Miles Smith used the same phrase in "The Translators to the Reader", the lengthy preface to the 1611 King James Bible, but by the seventeenth century the phrase had become very widespread indeed and had clearly achieved the status of a fixed phrase with allusive, quasi-proverbial, force.

Examples of usage

In different literary hands, it could be used either earnestly, or mockingly.[11] Benjamin Keach (1689) falls into the former camp: "I know not.. / whether those who did our Rights betray, / And for a mess of Pottage, sold away / Our dear bought / Freedoms, shall now trusted be, / As Conservators of our Libertie."[12] As does Henry Ellison (1875) "O Faith .. The disbelieving world would sell thee so; / Head turned with sophistries, and heart grown cold, / For a vile mess of pottage it would throw / Away thy heritage, and count the gold!".[13] Karl Marx' lament in Das Kapital has been translated using this phrase: The worker "is compelled by social conditions, to sell the whole of his active life, his very capacity for labour, in return for the price of his customary means of subsistence, to sell his birthright for a mess of pottage."[14]

Swift and Byron use the phrase satirically: "Thou sold'st thy birthright, Esau! for a mess / Thou shouldst have gotten more, or eaten less."[15] The Hindu nationalist V. D. Savarkar borrowed the phrase, along with quotations from Shakespeare, for his pamphlet Hindutva (1923), which celebrated Hindu culture and identity, asking whether Indians were willing to 'disown their seed, forswear their fathers and sell their birthright for a mess of pottage'.

Perhaps the most famous use in American literature is that by Henry David Thoreau: "Perhaps I am more than usually jealous with respect to my freedom. I feel that my connection with and obligation to society are still very slight and transient. Those slight labors which afford me a livelihood, and by which it is allowed that I am to some extent serviceable to my contemporaries, are as yet commonly a pleasure to me, and I am not often reminded that they are a necessity. So far I am successful. But I foresee that if my wants should be much increased, the labor required to supply them would become a drudgery. If I should sell both my forenoons and afternoons to society, as most appear to do, I am sure that for me there would be nothing left worth living for. I trust that I shall never thus sell my birthright for a mess of pottage. I wish to suggest that a man may be very industrious, and yet not spend his time well. There is no more fatal blunderer than he who consumes the greater part of his life getting his living."[16]

Another prominent instance of using the phrase in American fiction is James Weldon Johnson's famous protagonist Ex-Coloured Man who, retrospectively reflecting upon his life as a black man passing for white, concludes that he has sold his "birthright for a mess of pottage".[17]

By a conventional spoonerism, an overly propagandistic writer is said to have "sold his birthright for a pot of message." Terry Pratchett has his character Sergeant Colon say this in Feet of Clay, after Nobby of the Watch has guessed that the phrase is “a spot of massage.” Theodore Sturgeon had one of his characters say this about H. G. Wells in his 1948 short story Unite and Conquer; but Roger Lancelyn Green (in 1962) ascribed it to Professor Nevill Coghill, Merton Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford.

The phrase also appears in Myra Brooks Welch's poem "The Touch of the Master's Hand," in which "a mess of pottage — a glass of wine — a game" stand for all such petty worldly pursuits, contrasted to life after a spiritual awakening.

The phrase also appears in the 1919 African-American film Within Our Gates, as used by the preacher character 'Old Ned' who having ingratiated himself by acting the clown with two white men turns away and states, "again, I've sold my birthright. All for a miserable mess of pottage."

Notes

- See Old Testament figures in art, by Chiara de Capoa, ed. by Stefano Zuffi, tr. by Thomas Michael Hartmann (Los Angeles : Getty Museum, 2003), pp. 111–112.

- See Middle English Dictionary s.v. "mes n."

- John capgrave, "A Treatise of the Orders under the Rule of St. Augustine," in John Capgrave's Lives of St. Augustine and St. Gilbert..., ed. by J. J. Munro, EETS 140 (London, 1910), p. 145.

- Desiderius Erasmus, A booke called in latyn Enchiridion militis christiani, and in englysshe the manuell of the christen knyght, (London : Wynkyn de Worde, 1533).

- Desiderius Erasmus, The first tome or volume of the Paraphrase of Erasmus vpon the Newe Testamente [s.v. Luke, chap. 4] (London : Edward Whitchurche, 1548)

- The thre bokes of cronicles, whyche Iohn Carion ... gathered wyth great diligence of the beste authours (London, 1550).

- Sermons very fruitfull, godly, and learned, preached and sette foorth by Maister Roger Edgeworth (London, 1557): "Esau...for a messe of potage sold his first frutes."

- Matthew's Bible : a facsimile of the 1537 edition, (Peabody, MA : Hendrickson, 2009).

- The Geneva Bible : a facsimile of the 1560 edition (Peabody, MA : Hendrickson, 2007).

- , OED DRAFT REVISION Dec. 2009, s.v. mess n.(1), sense 2.

- See A Dictionary of Biblical tradition in English Literature, ed. by David Lyle Jeffrey (Grand Rapids : Eerdmans, 1992), s.v. "birthright."

- Benjamin Keach, Distressed Sion Relieved (London, 1689), line 3300.

- Henry Ellison "Skepticism" in Stones from the Quarry (1875).

- Das Kapital, Volume One, Part III, Chapter "The Working Day". The original German text has ein Gericht Linsen, which literally means "a lentil dish".

- Byron, "The Age of Bronze," lines 632–3. Cp. Jonathan Swift, "Robin and Harry," line 36: "Robin ... swears he could get her in an hour, / If Gaffer Harry would endow her; / And sell, to pacify his wrath, / A birth-right for a mess of broth."

- Thoreau, Henry David, Life without principle (1854)

- James Weldon Johnson, The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man (New York, 1989), p. 211.