Metal Slader Glory

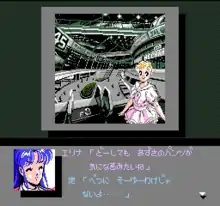

Metal Slader Glory is an adventure game developed and published by HAL Laboratory and released for the Famicom in 1991. The game is set in 2062 after humans have colonized the Moon and established several space stations. Earth-based mechanic Tadashi and his girlfriend discover a mech from a war eight years past with an ominous message stored in its memory suggesting Earth is in danger. Tadashi decides to venture to nearby space colonies along with Elina and his younger sister Azusa to investigate the origins of the mech. As Tadashi, the player speaks with other characters and picks dialogue and action commands to advance the narrative.

| Metal Slader Glory | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | HAL Laboratory |

| Publisher(s) | HAL Laboratory |

| Director(s) | Yoshimiru Hoshi |

| Platform(s) | Famicom |

| Release |

|

| Genre(s) | Adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

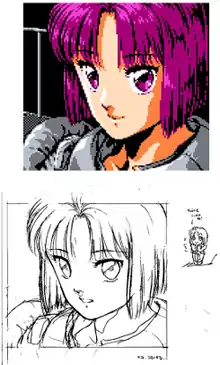

Development was led by artist Yoshimiru Hoshi, who was contracted to develop the game after Satoru Iwata of HAL was impressed by his character graphics. Yoshimiru wrote the script and was responsible for the game artwork. Although the Famicom had limited graphical capabilities and relied on the use of tilesets for artwork, he used advanced graphical techniques so his pixel art mirrored his manga-style pencil work. The detail placed on the graphics extended the game's development for four years.

The long development time and advanced graphics made Metal Slader Glory the largest Famicom game and one of the costliest to develop. It required a special chip which made the carts expensive to produce. Nintendo only sold enough chips to HAL so they could produce one run. The game was met with mixed reviews, and although the first run sold out, it did not cover the game's advertising budget. The game placed a large financial strain on HAL Laboratory. As the company drove towards bankruptcy, they ceased independent publishing and entered a close affiliation with Nintendo.

Yoshimiru considers Metal Slader Glory his life work. He has continued to explore the universe through manga and other works. A remake for the Super Famicom was released in 2000 on Nintendo Power flash cartridges, and was the last game released for the system. Both the original and remake were later released on the Virtual Console in Japan. A fan translation was released in 2018.

Synopsis

Gameplay

Metal Slader Glory is an adventure game.[1] The player talks with characters to advance the story, often making choices of things to do or say. Some choices may result in a game over. When the player chooses to rest at certain points in the story, they are given a password they can use to return to that point in the game.[2]

Plot

The story is set in 2062,[3] eight years after a great war between space colonies. The player takes on the role of Tadashi, a heavy machines operator based on Earth. After buying a worker mech for his business with his girlfriend Elina, they discover it is actually a "Metal Slader", a military grade mech used during the war. The machine holds a secret message saying Earth is in danger and to seek the "creator". Tadashi, Elina and his younger sister Azusa decide to fly to the nearby space stations and colonies near Earth and the Moon to investigate the mech's origins and the meaning of the strange message.

Tadashi and crew soon learn that their Slader is a particularly powerful one-of-a-kind model named "Glory" and Tadashi's deceased father was its former pilot. As they continue to search for who may have designed or built Glory, a shape-shifting alien infiltrates their ship and kidnaps Azusa. In their search for Azusa and solving the mysteries of Glory, they discover a secret organization of Slader pilots that had worked with Tadashi's father. Catty, one of the leaders of the organization, explains that they were founded by a now deceased Slader designer. She also explains how the war from eight years ago was not fought between colonies but with extraterrestrials; the colony rebellion story was a cover-up. Because the aliens have the ability to take on the appearance of humans and infiltrate society, the Slader pilots prefer to stay a secret organization away from the potentially compromised government. She continues, saying that they will soon launch an attack on the aliens, and want Tadashi to participate as only he can pilot Glory. Tadashi agrees, but first they set off in search of Azusa.

Tadashi, Elina, and Catty travel to an abandoned colony to search for Azusa. After combating with several aliens, they find Azusa alive and lodged in a ventilation shaft. As they return to the secret base, they learn its location has been compromised. They escape on a large ship and prepare the Sladers for battle. Tadashi pilots Glory in a battle with the aliens and is ultimately successful at destroying their ship and saving Earth.

Development

Background

.jpg.webp)

Development of Metal Slader Glory was led by artist Yoshimiru Hoshi (typically referred to by his first name). Early in his career in the 1980s, Yoshimiru was only interested in anime and plastic models and had primarily worked on artwork for hobby and model magazines during a wave of Gundam model popularity.[4] He was also writing a manga called Fixallia, which was cancelled before he could conclude the story.[5] Yoshimiru began working on video game strategy guides when Nintendo's home video game console, the Famicom, experienced a surge in popularity in the 1980s; it was then that he first gained an interest in games. The editorial company he worked for, Work House, let students rent space to work on personal projects, so Yoshimiru took this opportunity to learn from his colleagues how to create pixel art and animations. Once he was convinced he could create manga-style artwork with computers, he began creating Famicom artwork regularly.[4]

Yoshimiru began doing freelance work for HAL Laboratory while at Work House.[4] HAL Laboratory was a successful independent video game developer and publisher.[5] They were primarily building tools and technology to aid in development, but the success of the Famicom drove them to start developing their own games.[4] Yoshimiru did artwork for games such as Gall Force, Keisan Game: Sansuu 5+6 Nen, and Fire Bam. HAL prepared a desk so he could work from the main office in Kanda, Tokyo.[4] Students and freelancers were proposing projects to HAL at this time,[4] so Yoshimiru began working on an original game based upon his cancelled Fixallia manga.[5] From his experience with the Famicom hardware, he was able to create character portraits with blinking eyes and mouth animations.[6] As he was preparing his presentation, the head of development at HAL, Satoru Iwata, walked by and saw the game, and gave Yoshimiru project approval on the spot without needing to give a presentation. Yoshimiru believes the graphics, particularly the large animated characters, looked more advanced than any other Famicom artwork at the time and this is what won over Iwata.[4]

Planning

Development on Metal Slader Glory began in 1987.[4][6] Yoshimiru lead the project, writing the script, planning the gameplay, creating sound effects, and drawing the artwork and animations.[4] He was given complete creative control over the project,[4][5] except for music composition.[5] He did not assist with programming either.[4] Iwata served as a pseudo producer and assisted with programming.[7] He was a contracted worker, so would only make money from royalties following the game's release. Since he was still living with his parents at the time, this was not a significant hardship.[4] It took HAL a few months to pull together a team for Yoshimiru. During this time, he worked on the script. Since the game would have branching scenarios, he felt as though he was writing a gamebook.[6]

Once a team was built, Yoshimiru spent the first six months working with programmers to help them understand the type of game he wanted to build. While the programmers spent three months creating the basic framework for the game, Yoshimiru worked on the script.[4] He would first create flowcharts to show how the story would unfold, then write the script based on the flowcharts.[6] As there were no word processors at the time, all this work was handwritten.[4] Once the script was around 80% complete, the team started discussing whether the game could fit in a Famicom cartridge or not.[6] They ultimately had to cut more than half of Yoshimiru's original script from the final game.[6]

Graphics

After the first year of planning, the team spent the next three years programming and rendering graphics.[5] The graphics in Metal Slader Glory were the most difficult and time-consuming part of the project.[4][6] The Famicom was not capable of displaying freely drawn graphics,[5] instead using tile-based graphics and only displaying a limited number of unique tiles at any time. The hardware was capable of holding 128x128 pixels worth of data in "banks" which held the tiles to be displayed on screen at any one time. All image data had to be broken down to 8x8 tiles to fit within a bank.[4] One of these banks only filled a quarter of the screen,[6] and sprite data took up another quarter,[4] so to display larger and more elaborate scenes, the team had to use repeat tiles from the bank or draw some sprites to the background.[4][6] Most games of the era repeated 16x16 tiles for the background, and each tile was limited to a palette of three colors. As using an entirely different color palette on blocks adjacent to each other would make the boundaries obvious, so the artists had to plan artwork carefully to hide these boundaries and create convincing large images.[4] Working with the tiles to create impressive imagery and save space was the main reason for the game's protracted development.[4]

Yoshimiru created his artwork with home television sets in mind versus the professional video monitors used in the office.[4] Before creating pixel art, he would always draw his ideas first. When transferring his ideas into computer graphics, he conveyed his pencil work through careful use of color. He placed medium shades between dark and light shades, effectively a fake anti-aliasing technique.[4] Three assistants helped with converting his pencil drawings to pixel art.[8] Animation was also important to Yoshimiru, so he made sure to add expression and emotion into each scene. The system had limited memory, so he reused animated character portraits throughout the game.[6] These space limitations restricted some of Yoshimiru's artistic vision.[5]

Speech

The game features patterned sounds to represent speech. This was somewhat revolutionary at the time as most other games used the same repeating tones to represent speech. Initially there were five sounds used that would play alternately depending on the letters in the dialogue, but this variation made the speech sound too much like music. The speed of the text was made different between characters after Yoshimiru spoke with a programmer who said it was possible to sync the text and speech sound.[6] Some of the more risque text was censored later in development, as well as visuals.[4][6]

Size and cost issues

Development of Metal Slader Glory lasted a long four years,[5] and with one megabyte of data,[9] was the largest game for the Famicom.[5] The team disbanded after production.[5] It was one of the costliest games produced for the Famicom. In retrospect, Iwata believed there were management mistakes with the game.[7] At points in development, the team considered releases on other systems. A multidisk release for the Famicom Disk System was considered. Also, when Nintendo revealed the system architecture for their next home console, the Super Famicom, the team believed they could potentially transfer their progress to the new platform. This decision was not up to Yoshimiru, and ultimately development was completed for the Famicom.[4] When it became clear there was not enough space to fit the opening Yoshimiru wanted into the game, he spoke to HAL's public relations representative and got approval to include it as a manga in the manual.[6]

The final game was built with an MMC5 chip, chosen for its parallax scrolling capabilities. The game could have otherwise been achievable on a less advanced MMC3 chip.[4] The MMC5 chips made the carts more expensive to manufacture. Nintendo sold a limited number of boards to HAL at a discount so they could afford to sell Metal Slader Glory at a competitive market price[5] of 8900 yen.[10] It is unknown why Nintendo only sold a limited number of the boards; HAL could only produce a limited number of copies due to this restriction.[5][7]

Release

Metal Slader Glory was released for the Famicom in Japan on 30 August 1991,[10] nearly a year after the release of the Super Famicom.[4] HAL was responsible for marketing the game,[5] and the first production run sold quickly,[6] but the sales were not enough to cover the game's advertising budget.[5] The game had tough competition from Super Famicom games like Final Fantasy IV.[5] HAL requested a second print run but at the time HAL's development and sales departments were separating, so they were unable to get their request granted and no more copies were produced.[6] The game's subsequent rarity made it one of the most well known expensive games in Japan through the 1990s.[6]

The long development cycle, expensive cartridges, and lack of sales brought on financial strain to HAL Laboratory.[5] Beyond Metal Slader Glory, the company's growing success through the late 1980s pressured programmers to release games faster and place less effort on quality. Sales were generally not strong enough to recoup development costs, and the company nearly fell into bankruptcy.[5] In 1992, Nintendo offered to rescue HAL from bankruptcy on the condition that Iwata was appointed as HAL's president.[7] It was later rereleased on the Wii via the Virtual Console on 18 December 2007.[11] Although this release delighted Yoshimiru as it gave more people an opportunity to play it, he was disappointed they would not understand the back story included with the original game manual.[6] It was released for the Wii U Virtual Console on 1 July 2015.[12]

Director's Cut

Metal Slader Glory was remade for the Super Famicom as Metal Slader Glory: Director's Cut,[5][13] published by Nintendo.[14] It was the last officially released game for the system,[15] and was distributed exclusively for Nintendo Power flash cartridges.[5][13] The game was first made available on 29 November 2000 on pre-written cartridges, and came with collectible postcards. It could be written to existing cartridges starting on 1 December.[16] Players wanting the game would bring their Nintendo Power cartridge to a download station, and pay a fee to copy the game to the cartridge.[17]

This version features improved graphics and additional story sequences cut from the original game due to size constraints.[18][19][20] The team was composed of mostly new talent instead of the old team.[5] This time around, Yoshimiru did not experience any graphics limitations as he did with the original.[5] Since his artistic style had changed over time, he created the new artwork based on the originals, adding colors, highlights, and shadows.[21] The original music could not be used because of copyright, so the composer wrote new music.[20]

Yoshimiru felt the game was a great opportunity for those that could not afford the original or fans that wanted to revisit it.[6] Like with the Wii rerelease of the original later, the game did not include the back story featured in the original manual.[6] This version was released on the Wii U Virtual Console on 9 December 2015.[13]

Reception

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Famitsu | (FC) 23/40[10] |

| PlayStation Magazine (JP) | (FC) 21.8/30[22] |

| Yuge | (FC) Positive[23] |

Contemporary reviews were mixed. The change in genre between scenes confused some critics. For example, sometimes the player would explore a dungeon while other times it would turn into a shooting game.[5] Micom BASIC compared the game to adventure games on personal computers, and praised the high quality graphics and grand story.[24][25] Fan reception was positive: in a poll taken by Family Computer Magazine, it received a score of 21.8 out of 30, indicating a large popular following.[22] A writer at Japanese gaming magazine Yuge gave it a positive review.[23]

In retrospect, Waypoint complemented its "grand and ambitious scale."[5] Wired called it a cult classic.[26] ITmedia praised the game's visuals, character design, and animation, but complained about getting lost exploring some areas.[27]

Legacy

Yoshimiru has described Metal Slader Glory as his "life work".[5] Faminetsu agreed, writing that most people identify Yoshimiru primarily with Metal Slader Glory.[4] He wishes the game could be translated through legal channels.[5] A completed fan translation for the Famicom version was released on 30 August 2018.[28]

Yoshimiru has continued to explore the game's themes in his manga and other works.[5][6] There were two fan books,[29] a drama CD in 2010, and gashapon toys in 2011.[6][30] He has expressed interest in a follow-up adventure game set in the Metal Slader Glory universe, and would take it up if offered the chance to develop it as he cannot develop it on his own.[4][6] He has theorized a virtual reality headset game with a system that could react to the player's facial expressions.[4] A Metal Slader Glory game for the 64DD was planned and canceled.[31]

References

- "VC メタルスレイダーグローリー". Nintendo (in Japanese). 2007. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ゲームの進めかた. Nintendo (in Japanese). 2007. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- 4.『メタルスレイダーグローリー』開発スタッフインタビュー/ページ5. Nintendo (in Japanese). 2000. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ドット絵の匠 ファミコンで最も精緻なドット絵 ☆よしみる 編. ファミ熱!!プロジェクト (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018. (Translation Archived 26 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine)

- Crimmins, Brian (21 November 2017). "Why Does HAL Laboratory Only Make Nintendo Games?". Waypoint. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "【連載コラム】ゲームコレクター・酒缶の「RE:コレクション」:第55回(最終回)「休む」(『メタルスレイダーグローリー』)". GameSpot Japan (in Japanese). 26 March 2012. Archived from the original on 16 December 2012. (Translation Archived 26 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine)

- "Satoru Iwata – 1999 Developer Interview". Used Games (in Japanese). 1999. (Translation Archived 12 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine)

- 4.『メタルスレイダーグローリー』開発スタッフインタビュー/ページ1. Nintendo (in Japanese). 2000. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Cunningham, Andrew (15 July 2013). "The NES turns 30: How it began, worked, and saved an industry". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- メタルスレイダーグローリー [ファミコン]. Famitsu (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "VC メタルスレイダーグローリー". Nintendo (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "メタルスレイダーグローリー | Wii U | 任天堂". 任天堂ホームページ (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "メタルスレイダーグローリー ディレクターズカット | Wii U | 任天堂". 任天堂ホームページ (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- メタルスレイダーグローリー ディレクターズカット [スーパーファミコン]. Famitsu (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 6 December 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Eisenbeis, Richard (21 June 2013). "How Past Game Consoles Said Goodbye in Japan". Kotaku. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- メタルスレイダーグローリー ディレクターズカット. Nintendo (in Japanese). 2000. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Kalata, Kurt (27 December 2014). "Genjuu Ryodan". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Spencer (30 November 2007). "Discover Treasure Hunter G and Pokemon Snap on the virtual console". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- メタルスレイダーグローリー ディレクターズカット. Nintendo (in Japanese). 2000. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- 4.『メタルスレイダーグローリー』開発スタッフインタビュー/ページ4. Nintendo (in Japanese). 2000. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- 4.『メタルスレイダーグローリー』開発スタッフインタビュー/ページ3. Nintendo (in Japanese). 2000. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- 超絶 大技林 '98年春版: ファミコン - メタルスレイダーグローリー. PlayStation Magazine (Special) (in Japanese). 42. Tokuma Shoten Intermedia. 15 April 1998. p. 139. ASIN B00J16900U.

- "ユーゲーが贈るファミコン名作ソフト 100選 - メタルスレイダーグローリー". Yuge (in Japanese). Vol. 7 no. 10. Kill Time Communication. 1 June 2003. p. 49.

- "Challenge Adventure Game: メタルスレイダーグローリー". Micom BASIC Magazine (in Japanese). No. 115. The Dempa Shimbunsha Corporation. January 1992. pp. 226–228.

- "Challenge Adventure Game: メタルスレイダーグローリー". Micom BASIC Magazine (in Japanese). No. 116. The Dempa Shimbunsha Corporation. February 1992. pp. 222–224.

- Kohler, Chris (30 November 2007). "Japan VC: Metal Slader Glory, Treasure Hunter G". Wired. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "ゲイムマンの「レトロゲームが大好きだ」:「メタルスレイダーグローリー」が600Wiiポイントで買える!". ITmedia (in Japanese). 10 February 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Reese, Zack (1 September 2018). "Metal Slader Glory has finally been fan translated into English". RPG Site. Mist Network. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- "メタルスレイダーグローリーファンブック リマスター / レトロゲーム総合配信サイト、プロジェクトEGG". Amusement Center (in Japanese). 2013. Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Caoili, Eric (12 April 2011). "GameSetWatch SR Video Game Robotics Features Border Break, Metal Slader Glory Figures". GameSetWatch. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Hoshi, Yoshimiru (2013). 幻のゲーム企画の真相!! 『SFCメタルスレイダーグローリー』 (in Japanese). Mc Berry's. p. 4.

External links

- Metal Slader Glory Virtual Console page (in Japanese)

- Metal Slader Glory: Director's Cut official website (in Japanese)