Metodija Andonov-Čento

Metodija Andonov-Čento (Macedonian: Методија Андонов Ченто; Bulgarian: Методи Андонов Ченто) (17 August 1902 – 24 July 1957) was a Macedonian statesman, the first president of the Anti-Fascist Assembly of the National Liberation of Macedonia and of the People's Republic of Macedonia in the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia after the Second World War. In Bulgaria he is often considered a Bulgarian.[1][2][3]

Metodija Andonov-Čento Методија Андонов Ченто | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 August 1902 |

| Died | 24 July 1957 (aged 54) Prilep, PR Macedonia, FPR Yugoslavia |

| Nationality | Macedonian |

| Organization | Yugoslav Partisans (People's Liberation Army of Macedonia); ASNOM (Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia) |

Early life

Metodi Andonov was born in Prilep, which was then part of the Manastir Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire. He was the first healthy child of Andon Mitskov and Zoka Koneva, as his older siblings bore diseases. His father was from Pletvar, while his mother was from Lenište. As a child, he worked in opium poppy fields and harvested tobacco. After the Balkan Wars in 1913 the area was ceded to Serbia, where a serbianization was implemented,[4] while many Macedonians who had clear ethnic consciousness then, believed they were Bulgarians.[5] However in the early 20th century a process of slow differentiation between Bulgarian and Macedonian as a national belonging occurred.[6] During the World War I Bulgarian occupation the authorities in most of Vardar Macedonia consisted of local activists and thus were popular enough there.[7] After the war the area was ceded to the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), where Čento graduated from a trade school. During his adolescence, he was considered to be an excellent gymnast. In the interwar period the young local intelligentsia attempted at a separate Macedonian way of national development.[8] Čento underwent such a transformation from pro-Bulgarian to an ethnic Macedonian.[9]

Interwar period

In 1926 he opened a shop and was engaged in retail trade and politics. On 25 March 1930 he married Vasilka Spirova Pop Atanasova in Novi Sad and fathered four children. At that time Čento headed a group of young Macedonian nationalists, who took up decidedly an anti-Serbian position. In fact the politicians in Belgrade actually helped to strengthen the developing Macedonian identity by promoting forcible Serbianization. He was a sympathizer of Vladko Macek's idea on the creation of a separate Banovina of Croatia and after its realization in 1939 proclaimed the thesis on the foundation of a separate Banovina of Macedonia. At the 1938 Yugoslav elections, he was elected deputy from the Croatian Peasant Party, but didn't become a Member of Parliament because of a manipulation with the electoral system. In 1939, he was imprisoned at Velika Kikinda for co-organizing the anti-Serbian Ilinden Demonstrations in Prilep. The following year, he imposed the use of the Macedonian language in school lectures and was therefore imprisoned at Bajina Bašta and sentenced to death by the government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia for advocating the use of a language other than Serbo-Croatian. On 15 April 1941 he was presented to a firing squad, but was pardoned just prior to being shot, due to the public pressure on the background of the Blitzkrieg conducted by the Axis Powers during their invasion of Yugoslavia.

World War II in Yugoslav Macedonia

In April 1941, when the Bulgarian Army entered the area, it was greeted as alleged liberator from Serbian rule, while pro-Bulgarian feelings still prevailed among the local population.[10] During the early stages of Bulgarian annexation of most of the Vardar Macedonia, Čento was set free from the Yugoslav prison and came in contact with the right-wing Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) activists and pro-Bulgarian political forces.[11] The Macedonian communists also fell in the sphere of influence of the Bulgarian Communist Party under Metodi Shatorov's leadership, with whom Čento was also in close contact. However, when in June the USSR was attacked by Nazi Germany, the Comintern issued a supreme decision that the Macedonian Communists must be re-attached to the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. Meanwhile, the Bulgarian authorities staffed the new province with corrupted officials from Bulgaria proper and soon began to lose the public confidence. Although he received at that time an invitation to collaborate with the new administration Čento refused, considering that idea unpromising and insisting on independence. In 1942 Čento began to sympathize with the resistance and his store was used as a front for the Macedonian communists, which prompted Bulgarian authorities to arrest him. For this reason by the end of 1942 he was interned in the inland of the country and later sent to a labor camp. Meanwhile, although several partisan detachments were formed through the end of 1942 and despite Sofia's ill-managed administration, most Macedonian Communists had yet to be lured to Yugoslavia.

In 1943 the Yugoslav communists changed the course and proclaimed as their aim the issue of unification of the region of Macedonia, and so managed to get also the Macedonian nationalists. Upon his release in the fall of 1943, Cento met Kuzman Josifovski, a member of the General Staff of the Partisan units of Macedonia, who convinced him to join them. As result Čento moved to the German occupation zone of Vardar Macedonia, then part of Albania, where he became a member of the General Staff of the resistance. Until the spring of 1944 the Macedonian partisan activity was concentrated in this part of then Albanian territory. As the most authoritative figure in December 1943, Andonov-Chento was elected to chair the ASNOM Convening Committee. In June 1944, he, Emanuel Čućkov and Kiril Petrušev left for island of Vis to meet with the People's Liberation Committee of Yugoslavia headed by Josip Broz Tito. The meeting was held on June 24, with the Macedonian delegation raising the issue of United Macedonia after the German retreat. In August 1944, he was elected as President of Anti-Fascist Assembly of the National Liberation of Macedonia. At his initiative, at its first meeting were invited former IMRO activists, related to the Bulgarian Action Committees, who he wanted to associate to the administration of the future state. In September however, Nazi Germany briefly sought to establish a puppet state called Independent State of Macedonia, where they participated.

Čento's goal was to create a fully independent United Macedonian state, but after by mid-November 1944 the Partisans had established military and administrative control of the region, it became clear that Macedonia should be constituent republic within the new SFR Yugoslavia. Čento saw this as a second period of Serbian dominance in Macedonia and insisted on independence for the republic from the federal Yugoslav authorities. In this way, he clashed with Svetozar Vukmanović-Tempo, Josip Broz Tito's envoy to Macedonia and Lazar Koliševski, the leader of the ruling Communist Party of Macedonia.

Post-war era and death

The new communist authorities started a policy fully implementing the pro-Yugoslav line and took hard measures against the opposition. They carried out a large number of arrests and killings of pro-Bulgarian elements called fascist, collaborators, etc. The Macedonian national feelings were already ripe at that time as compared to 1941, but some pro-Bulgarian sentiments still harbored in the locals.[12] Such feelings were available even in Čento himself,[13] who as noncommunist favored the collaboration with the so-called Bulgarophiles.[14] He publicly condemned the killings in parliament and sent a protest to the Macedonian Supreme Court. He supported the Skopje soldiers' rebellion when officers from the Gotse Delchev Brigade formed in Sofia, mutinied in the garrison stationed in Skopje Fortress, but were suppressed by an armed intervention.[15] They as himself opposed sending the new Macedonian army to the Syrmian Front. Čento wanted to send it to Thessaloniki, then abandoned by the Germans, for the purpose of creating a United Macedonia. He also opposed the planned return of Serbian colonists, expelled by the Bulgarians. By the voting of Art. 1 of the new constitution of the SFRY, which lacked the ability of the constituent republics to leave the federation, he defiantly left the parliament in Belgrade. After disagreement with the policies of Communist Yugoslavia and after several clashes with the new authorities, Čento resigned.

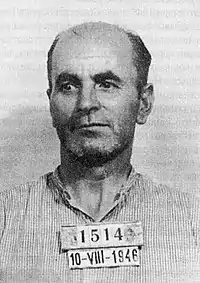

In 1946, he went back to Prilep, where he established contacts with illegal anti-Yugoslav group, with ideas close to these of the banned Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, which insisted on Independent Macedonia.[16][17] Čento openly called for Macedonia to secede from Yugoslavia and decided to go incognito at the Paris Peace Conference and to advocate for Macedonia's independence. He was arrested in the summer of 1946, after being caught reportedly crossing illegal the border with Greece in order to visit Paris.[18] In November 1946 Čento was brought before the Macedonian tribunal.[19] The court included high ranking communist-politicians as Lazar Mojsov and Kole Čašule. The fabricated charges against him were of being a Western spy, working against the SR Macedonia as part of SFR Yugoslavia, and being in contact with IMRO terrorist, who supported a pro-Bulgarian Independent Macedonia as envisaged by Ivan Mihajlov.[20][21][22] He was sentenced to eleven years in prison under forced labor.[23] He spent more than 9 years in the Idrizovo prison, but as a result of the conditions there, Cento became seriously ill and was released ahead of schedule. In his hometown, he worked digging holes for telegraph poles to save his four children from starvation. He died at home on 24 July 1957 after sickness from torture in prison. Thus, in communist Yugoslavia, his name became taboo, and when mentioned, he was described as a traitor and counter-revolutionary.

Legacy

Metodija Andonov-Čento was rehabilitated in 1991 with a decision of the Supreme Court of the newly proclaimed Republic of Macedonia in which it annulled the verdict against Čento from 1946. In 1992, his family and followers established a Čento Foundation, which initiated a lawsuit for damages against the Government of Macedonia. Before Čento was rehabilitated in 1991 in Macedonia he was often described by the Bulgarian communist historiography as a Bulgarian,[24] and up to this time is considered as such by some historians.[25][26][27] A similar view has been expressed by Hough Poulton and therefore criticized by Victor Friedman,[28] though this view is still found in the specialized literature.[29]

References

- Срещу тезата на Ченто за братство с българския народ се изправя самият Ранкович с едно свое обръщение към Павел Шатев, вече министър на правосъдието, на един прием при Тито след първото заседание на Камара на нациите: "Ща тражиш ти овде, бугарско куче?" Ченто е станал свидетел на това изстъпление. Връщайки се от Белград, той заявява на приятелите си: "Братя, измамени сме! Знайте, ние сме си българи и мислехме като македонци да минем моста. Уви! Няма живот сьс сърбите". Коста Църнушанов, "Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него", София, 1992 година, Унив. издателство "Св. Климент Охридски, стр 275-282.

- "Нова Македония” под надслов “Срещу тезите на Ченто” пише: “ Ние трябва да се борим срещу великобългарите, които днеска не могат открито да говорят, че Македония е българска страна и че македонците са македонски българи"...Най - жестока провокация срещу политическите разбирания на Методи Ченто, които ЮКП квалифицира като български, е извършена с избиването на 54 видни българи във Велес. Славе Гоцев, Борби на българското население в Македония срещу чуждите аспирации и пропаганда 1878-1945, София, 1991 година, Унив. издателство "Св. Климент Охридски, стр. 183-187.

- След 45 години в Република Македония се чуха гласове за реабилитацията на първия председател на народното събрание Методи Андонов - Ченто, но вече не като българин, а като "македонец...Ето какви са причините за разправата с Методи Андонов - Ченто, една от най-ярките личности в следвоенното развитие на Вардарска Македония, позволила си в онези мрачни времена на титовско-колишевския геноцид срещу българщината да изрази една различна от ЮКП, по същество българофилска позиция. Това всъщност се опитва да скрие казионният печат в Скопие, правейки плахи опити за неговата реабилитация, но скривайки истината защо всъщност той бе осъден по такъв безскрупулен начин на 11 години затвор." Веселин Ангелов, Премълчани истини: лица, събития и факти от българскарта история 1941-1989, библиотека Сите Българи заедно, Анико, 2005, стр. 42-44.

- Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996, Chris Kostov, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 65.

- John Van Antwerp Fine, "The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century," University of Michigan Press, 1991, ISBN 0472081497, pp. 36–37.

- Tchavdar Marinov, Famous Macedonia, the Land of Alexander: Macedonian Identity at the Crossroads of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian Nationalism in Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X, p. 303.

- Ivo Banac, "The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics", Cornell University Press, 1984, ISBN 0801494931, p. 318.

- Karen Dawisha et al. Politics, power, and the struggle for democracy in South-East Europe, Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-521-59733-3, p. 229.

- Коста Църнушанов. Обществено-политическата дейност на Методи Андонов—Ченто (непубликувана статия); сп. Македонски преглед, бр. 3, 2002 г. стр.101-113.

- Raymond Detrez, The A to Z of Bulgaria, G - Reference, SCARECROW PRESS INC, 2010, ISBN 0810872021, p. 485.

- Corina Dobos and Marius Stan as ed., History of Communism in Europe vol. 1, Zeta Books, 2010, ISBN 9731997857, p. 200.

- Loring M. Danforth, The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world, Princeton University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-691-04356-6, pp. 65-66.

- Hugh Poulton, Who are the Macedonians? Indiana University Press, 1995, ISBN 0253345987, pp. 118–119.

- Dimitar Bechev, Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Edition 2, Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, ISBN 1538119625, p. 16.

- Stefan Troebst, Das makedonische Jahrhundert: von den Anfängen der nationalrevolutionären Bewegung zum Abkommen von Ohrid 1893-2001; Oldenbourg, 2007, ISBN 3486580507, p. 247.

- Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 2, From the Fifteenth Century to the Present), Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, ISBN 1443888494, p. 294.

- Dimitar Bechev, Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Edition 2, Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, ISBN 1538119625, p. 148.

- Hugh Poulton, Who are the Macedonians? C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1850655340, p. 103.

- The Law for the Protection of Macedonian National Honour was passed in 1945. The act allowed the sentencing of citizens for collaboration, pro-Bulgarian sympathies, and contesting Macedonia’s status within Yugoslavia. The latter charge was used to sentence Metodij Andonov-Čento who opposed the authorities’ decision to join the federation without reserving the right to a secession and criticised it for not putting enough emphasis on Macedonian culture. For more see: Communist dictatorship in Macedonia. The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1945-1992). Communist crimes. Estonian Institute of Historical Memory.

- Paul Preston, Michael Partridge, Denis Smyth, British Documents on Foreign Affairs reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: Bulgaria, Greece, Roumania, Yugoslavia and Albania, 1948; Europe 1946-1950; University Publications of America, 2002; ISBN 1556557698, p. 50.

- Indiana Slavic Studies, Volume 10; Volume 48; Indiana University publications: Slavic and East European series. Russian and East European series, 1999, p. 75.

- Ivo Banac, With Stalin Against Tito: Cominformist Splits in Yugoslav Communism, Cornell University Press, 1988, ISBN 0801421861, p. 203.

- L. Benson, Yugoslavia: A Concise History, Edition 2, Springer, 2003, ISBN 1403997209, p. 89.

- БКП, Коминтернът и македонският въпрос (1917-1946). Колектив, том 2, 1999, Гл. управление на архивите. Сборник. стр. 1246-1247.

- Добрин Мичев, Македонският въпрос в Българо-югославските отношения (1944-1949). Университетско издателство "Св. Климент Охридски", 1994 г. стр. 77-86.

- Иван Николов, Време е Скопие да реабилитира Шарло и Ченто. 05 Юни 2019, Гласът на България.

- Цанко Серафимов, Енциклопедичен речник за Македония и македонските работи, Орбел, 2004, ISBN 9544960708, стр. 184.

- He is so eager to accept Bulgarian claims that he uncritically reproduces Bulgarian allegations without any indication of their context or veracity ("Who are the Macedonians?", Hugh Poulton 1995: 118 – 119). He even implies that Metodija Andonov - Čento, the first president of the Macedonian republic was a Bulgarophile rather than a Macedonian nationalist . For more see: "Macedonian Historiography, Language, and Identity, in the Context of the Yugoslav Wars of Succession", in Indiana Slavic Studies, Том 10; Том 48, Indiana University publications: Slavic and East European series Russian and East European series, Bloomington. p. 75.

- Bernard A. Cook, Andrej Alimov, Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Vol. 2; Taylor & Francis, 2001, ISBN 0815340583, Macedonia, p. 808.