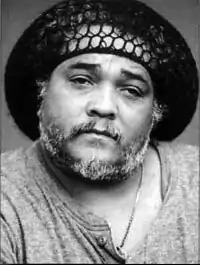

Michael Zinzun

Michael Zinzun (February 14, 1949 – July 9, 2006) was an African American ex-Black Panther and anti-police brutality activist .[1][2]

Michael Zinzun | |

|---|---|

Michael Zinzun | |

| Born | February 14, 1949 Chicago, IL |

| Died | July 6, 2006 (aged 57) Pasadena, CA |

| Occupation | Activist, Political Organizer |

| Organization | Coalition Against Police Abuse |

Early life

Zinzun was born in Chicago and lived in the Cabrini–Green housing projects during the early part of his childhood.[1] He told the LA Times that his mother was Black and his father was Apache, and that his father had eight other children.[1][2][3] His father died when he was eight at which point his mother sent him to live with an aunt in Pasadena, California.[1] He graduated from high school in Pasadena and made it his home for much of his life. After graduation he became an automobile mechanic and ran a repair shop in Altadena. When the land housing his garage was purchased by an oil company Zinzun was evicted and his business forced to close.[1]

Activism, political organizing, and lawsuits

In 1970 he joined the Black Panther Party, but only stayed two years, describing his work with the party as "an educational experience," but "[p]olitically, I felt it was stifling."[4][1] In 1974 he joined Los Angeles-area anti-police brutality activists B. Kwaku Duren and Anthony Thigpenn to form the Coalition Against Police Abuse (CAPA).[1] The organization investigates allegations of abuse, provides support for victims and families, and agitates for justice in street demonstrations and courtrooms. CAPA acknowledges a direct descent from the Black Panther Party, with many former BPP members, but is a distinct organization many of whose members critique what they see as the intensely hierarchical and patriarchal tendencies of the now defunct BPP.

Almost from the moment of CAPA's inception the LAPD infiltrated and placed it under surveillance. The techniques used by the LAPD in spying on and undermining the organization closely resembled those used by the FBI COINTELPRO program. CAPA was the lead plaintiff in a 1983 suit against the LAPD's Public Disorder Intelligence Division, which spied on citizens. CAPA won the suit, resulting in a monetary settlement, and the end of the Public Disorder Intelligence Division.[5]

After the 1979 police shooting death of Eulia Love in South Central Los Angeles CAPA proposed a civilian police review board, modeled on similar boards in other cities, that would have had the power to fire and otherwise discipline abusive police officers and change police policies. A petition in favor of the review board gained thousands of signatures, but not enough to place it on the ballot.[2]

In 1982, Zinzun was arrested for allegedly threatening police officers who were attempting to arrest two men in Pasadena.[2] Charges against him were later dropped. In 1986 Zinzun, hearing the commotion of a violent arrest, rushed to the scene to observe the arrest, resulting in police beating him severely. [6]The Pasadena police department accused him of striking an officer (Zinzun was never charged with such a crime) while Zinzun claimed that he was wrongfully forced to the ground, sprayed with mace, and beaten with a flashlight. As a result of the incident Zinzun was permanently blinded in one eye. Following the incident he is quoted as saying "I'd rather lose an eye fighting against injustice than live as a quiet slave."[1] He won a $1.2 million settlement from the department as a result of the events that night.[7]

In 1989 he ran for a seat on the Pasadena City Council. During his campaign the City of Los Angeles and an assistant chief of the LAPD disseminated information that falsely claimed that Zinzun was the subject of investigation by the department's anti-terrorism division. Zinzun sued for defamation and was awarded $3.8 million. This award was overturned on procedural grounds in a 1991 ruling. On further appeal Zinzun won $512, 500.[8]

Later career

After the 1992 Los Angeles riots, Zinzun and CAPA became much more successful in getting the attention of elected officials due to concerns about police brutality as the stimulus for social unrest. By the 1990s Zinzun was a familiar guest on local television news and debate programs. Unlike most guests he wore clothes with a Black Power aesthetic (a hair net, bright T-shirts with radical slogans, etc.) and spoke in a confrontational and direct manner, invariably signing off by raising his fist and proclaiming "Forward ever. Backwards never. All power to the people!"

Zinzun had a press pass, issued in Los Angeles, and for approximately ten years, he hosted and co-produced, with community activist and artist Nancy Buchanan, approximately 100 episodes of an hour-long monthly television show, "Message To The Grassroots." The program dealt with issues related to urban communities, and played on Pasadena Community Network's Channel 56 and at other access television stations in the U.S. Topics of shows included wounds inflicted by the Los Angeles Police Department K-9 corps, the Iran-Contra Affair and CIA connection to cocaine shipments into U.S. communities, apartheid in South Africa, the founding of Namibia, the political atmosphere in Haiti with guest commentator Ossie Davis, conflicts between black people and Latinos, and black-against-black gang issues. Zinzun was an outspoken advocate of a gang truce between rival Los Angeles gangs, and organized one of the first ever, face-to-face truce meetings on his television show between members of the Bloods and Crips. He presented a series of shows during the trial of the police officers accused of beating Rodney King, which included frame-by frame analyses of video tape of the incident by George Holliday, which led to alternative explanations of the police officers' behaviors. Zinzun discovered that a second camera had captured King immediately after the beating and he debuted that footage to the world. During the 1992 Los Angeles riots following the Rodney King decision, Zinzun was down among the burning buildings, on the streets, at the center of the event capturing rare video footage of rioters looting stores. He took cameras to Brazil and Namibia for episodes of the show. Zinzun took cameras into the center of controversial housing projects in South Central Los Angeles, like Nickerson Gardens and Imperial Courts in Watts, Los Angeles to talk directly with residents about their communities.

Zinzun remained active in community issues as he worked with at-risk youth. In the last years of his life, he explored an interest in the culinary arts at Le Cordon Bleu school in Pasadena. He died in his sleep in 2006.[5]

References

- "An Unreconstructed '60s Radical Still Takes His Case to the Streets". Los Angeles Times. 1986-07-27. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

Zinzun says he was the second of the 10 children of a full-blooded Apache Indian man and a black woman.

- "Michael Zinzun, 57; Ex-Black Panther Challenged Southland Police Agencies". Los Angeles Times. 2006-07-12. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- Dennis, Yvonne Wakim (2016-04-18). Native American almanac : more than 50,000 years of the cultures and histories of indigenous peoples. Hirschfelder, Arlene B.,, Flynn, Shannon Rothenberger. Canton, MI. ISBN 9781578596089. OCLC 946931890.

- "Michael Zinzun; police abuse watchdog; 57 | The San Diego Union-Tribune". legacy.sandiegouniontribune.com. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- Jul 13, re Coleman |; 2006 | 0 | (2006-07-12). "Michael Zinzun". Pasadena Weekly. Retrieved 2019-04-22.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Felker-Kantor, Max (2018-09-25). Policing Los Angeles : race, resistance, and the rise of the LAPD. Chapel Hill. p. 125. ISBN 9781469646848. OCLC 1054642945.

- "Police Injury Suit Settled for $1.2 Million : Pasadena Agrees to Pay Community Activist Blinded in One Eye". Los Angeles Times. 1988-02-03. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- "Political Activist Zinzun Awarded $512,500 to Settle Suit With City : Police: Former Pasadena City Council candidate claimed he was defamed by LAPD official who released information about him". Los Angeles Times. 1994-07-28. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-04-22.

- Kevin Uhrich and André Coleman, contributing by Tracy Spicer (2006-07-13). "Michael Zinzun 1949-2006: Ex-Black Panther spent much of his time and money battling for social justice". Pasadena Weekly. Archived from the original on 2006-10-17. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

- Vargas, Joao H. Costa (2006). Catching Hell in the City of Angels: Life and Meanings of Blackness in South Central Los Angeles. University of Minnesota Press.