Ossie Davis

Raiford Chatman "Ossie" Davis (December 18, 1917 – February 4, 2005) was an American actor, director, writer, and activist.[1][2][3]

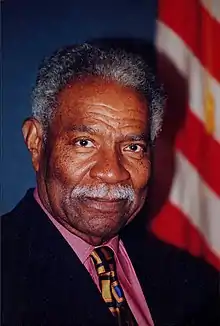

Ossie Davis | |

|---|---|

Davis in 2000 | |

| Born | Raiford Chatman Davis December 18, 1917 Cogdell, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | February 4, 2005 (aged 87) |

| Occupation | Actor, director, poet, playwright, author, activist |

| Years active | 1939–2005 |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3, including Guy Davis |

He was married to Ruby Dee (died June 11, 2014), with whom he frequently performed, until his death.[4]

He and his wife were named to the NAACP Image Awards Hall of Fame; were awarded the National Medal of Arts[5] and were recipients of the Kennedy Center Honors. He was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame in 1994.

Early life

Raiford Chatman Davis was born in Cogdell, Georgia, the son of Kince Charles Davis, a railway construction engineer, and his wife Laura (née Cooper; July 9, 1898 – June 6, 2004).[6][7] He inadvertently became known as "Ossie" when his birth certificate was being filed and his mother's pronunciation of his name as "R. C. Davis" was misheard by the courthouse clerk in Clinch County, Ga.[8] Davis experienced racism from an early age when the KKK threatened to shoot his father, whose job they felt was too advanced for a black man to have. His siblings included scientist William Conan Davis, social worker Essie Morgan Davis, pharmacist Kenneth Curtis Davis, and biology teacher James Davis.[9]

Following the wishes of his parents, he attended Howard University but dropped out in 1939 to fulfill his desire for an acting career in New York after a recommendation by Alain Locke; he later attended Columbia University School of General Studies. His acting career, which spanned eight decades, began in 1939 with the Rose McClendon Players in Harlem. During World War II, Davis served in the United States Army in the Medical Corps. He made his film debut in 1950 in the Sidney Poitier film No Way Out.

Career

When Davis wanted to pursue a career in acting, he ran into the usual roadblocks that black people suffered at that time as they generally could only portray stereotypical characters such as Stepin Fetchit. Instead, he tried to follow the example of Sidney Poitier and play more distinguished characters. When he found it necessary to play a Pullman porter or a butler, he played those characters realistically, not as a caricature.

In addition to acting, Davis, along with Melvin Van Peebles and Gordon Parks, was one of the notable black directors of his generation: he directed movies such as Gordon's War, Black Girl and Cotton Comes to Harlem. Along with Bill Cosby and Poitier, Davis was one of a handful of black actors able to find commercial success while avoiding stereotypical roles prior to 1970, which also included a significant role in the 1965 movie The Hill alongside Sean Connery plus roles in The Cardinal and The Scalphunters. However, Davis never had the tremendous commercial or critical success that Cosby and Poitier enjoyed. As a playwright, Davis wrote Paul Robeson: All-American, which is frequently performed in theatre programs for young audiences.

In 1976, Davis appeared on Muhammad Ali's novelty album for children, The Adventures of Ali and His Gang vs. Mr. Tooth Decay.[10]

_-_NARA_-_542018.tif.jpg.webp)

Davis found recognition late in his life by working in several of director Spike Lee's films, including Do The Right Thing, Jungle Fever, She Hate Me and Get on the Bus. He also found work as a commercial voice-over artist and served as the narrator of the early-1990s CBS sitcom Evening Shade, starring Burt Reynolds, where he also played one of the residents of a small southern town.

In 1999, Davis appeared as a theater caretaker in the Trans-Siberian Orchestra film The Ghosts of Christmas Eve, which was released on DVD two years later.

For many years, he hosted the annual National Memorial Day Concert from Washington, DC.

He voiced Anansi the spider on the PBS children's television series Sesame Street in its animation segments.

Davis's last role was a several episode guest role on the Showtime drama series The L Word, as a father struggling with the acceptance of his daughter Bette (Jennifer Beals) parenting a child with her lesbian partner. In his final episodes, his character was taken ill and died. His wife Ruby Dee was present during the filming of his own death scene. That episode, which aired shortly after Davis's own death, aired with a dedication to the actor.[11] After Davis's passing, actor Dennis Haysbert portrayed him in the 2015 film Experimenter.

Honors

In 1989, Ossie Davis and his wife, actress/activist Ruby Dee, were named to the NAACP Image Awards Hall of Fame. In 1995, they were awarded the National Medal of Arts, the nation's highest honor conferred to an individual artist on behalf of the country and presented in a White House ceremony by the President of the United States.[12] In 2004, they were recipients of the prestigious Kennedy Center Honors.[13] According to the Kennedy Center Honors:

- "The Honors recipients recognized for their lifetime contributions to American culture through the performing arts— whether in dance, music, theater, opera, motion pictures, or television — are selected by the Center's Board of Trustees. The primary criterion in the selection process is excellence. The Honors are not designated by art form or category of artistic achievement; the selection process, over the years, has produced balance among the various arts and artistic disciplines."[14]

In 1994, Davis was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame.[15]

Activism

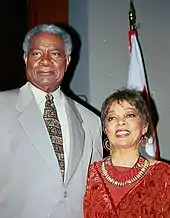

_with_Ossie_Davis_in_1998.jpg.webp)

Davis and Dee were well known as civil rights activists during the Civil Rights Movement and were close friends of Malcolm X, Jesse Jackson, Martin Luther King Jr. and other icons of the era. They were involved in organizing the 1963 civil rights March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and served as its emcees. Davis, alongside Ahmed Osman, delivered the eulogy at the funeral of Malcolm X.[16] He re-read part of this eulogy at the end of Spike Lee's film Malcolm X. He also delivered a stirring tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, at a memorial in New York's Central Park the day after King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee.

Personal life

In 1948, Davis married actress Ruby Dee, whom he had met on the set of Robert Ardrey's 1946 play Jeb. In their joint autobiography With Ossie and Ruby, they described their decision to have an open marriage, later changing their minds.[17] In the mid-1960s they moved to the New York suburb of New Rochelle, where they remained ever after.[18] Their son Guy Davis is a blues musician and former actor, who appeared in the film Beat Street (1984) and the daytime soap opera One Life to Live. Their daughters are Nora Davis Day and Hasna Muhammad.

Death

Davis was found dead in a Miami hotel room on February 4, 2005. An official cause of death was not released, but he was known to have had heart problems.[19]

Filmography

Film

- No Way Out (1950) as John Brooks (uncredited)

- Fourteen Hours (1951) as Cab Driver (uncredited)

- The Joe Louis Story (1953) as Bob (uncredited)

- Gone Are the Days! (aka Purlie Victorious) (1963) as Reverend Purlie Victorious Judson

- The Cardinal (1963) as Father Gillis

- Shock Treatment (1964) as Capshaw

- The Hill (1965) as Jacko King

- A Man Called Adam (1966) as Nelson Davis

- Silent Revolution (1967)

- The Scalphunters (1968) as Joseph Lee

- Sam Whiskey (1969) as Jed Hooker

- Slaves (1969) as Luke

- Wattstax (1973) as Himself (uncredited)

- Let's Do It Again (1975) as Elder Johnson

- Countdown at Kusini (1976) as Ernest Motapo

- Hot Stuff (1979) as Captain John Geiberger

- Benjamin Banneker: The Man Who Loved the Stars (1979)[20]

- Harry & Son (1984) as Raymond

- The House of God (1984) as Dr. Sanders

- Avenging Angel (1985) as Captain Harry Moradian

- School Daze (1988) as Coach Odom

- Do the Right Thing (1989) as Da Mayor

- Joe Versus the Volcano (1990) as Marshall

- Preminger: Anatomy of a Filmmaker (1991, Documentary) as Himself

- Jungle Fever (1991) as The Good Reverend Doctor Purify

- Gladiator (1992) as Noah

- Malcolm X (1992) as Eulogy Performer (voice)

- Cop and a Half (1993) as Detective in Squad Room (uncredited)

- Grumpy Old Men (1993) as Chuck

- The Client (1994) as Harry Roosevelt

- Get on the Bus (1996) as Jeremiah

- I'm Not Rappaport (1996) as Midge Carter

- 4 Little Girls (1997, Documentary) as Himself - Actor and Playwright

- Dr. Dolittle (1998) as Archer Dolittle

- Alyson's Closet (1998, Short) as Postman Extraordinaire

- The Unfinished Journey (1999, Documentary, Short) as Narration (voice)

- The Gospel According to Mr. Allen (2000, Documentary) as Narrator

- Dinosaur (2000) as Yar (voice)

- Here's to Life! (2000) as Duncan Cox

- Voice of the Voiceless (2001, Documentary) as Himself

- Why Can't We Be a Family Again? (2002, Documentary, Short) as Narrator (voice)

- Bubba Ho-Tep (2002) as Jack

- Unchained Memories (2003, Documentary) as Reader #6

- Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (2003, Documentary) as Himself

- Beah: A Black Woman Speaks (2003, Documentary) as Himself

- BAADASSSSS! (2003) as Granddad

- She Hate Me (2004) as Judge Buchanan

- Proud (2004) as Lorenzo DuFau

- A Trumpet at the Walls of Jericho (2005, Documentary)

Television

|

|

|

Directing

- Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970)

- Black Girl (1972)

- Gordon's War (1973)

- Kongi's Harvest (1973)

- Countdown at Kusini (1976)

- Crown Dick (1987 TV movie)

Theatre

Discography

|

Bibliography

- Davis, Ossie (1961). Purlie Victorious. New York: Samuel French Inc. Plays. ISBN 978-0-573-61435-4.

- Davis, Ossie (1977). Escape to Freedom: The Story of Young Frederick Douglass. New York: Samuel French. ISBN 978-0-573-65031-4.

- Davis, Ossie (1982). Langston. New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 978-0-440-04634-9.

- Davis, Ossie; Dee, Ruby (1984). Why Mosquitos Buzz in People's Ears (Audio). Caedmon. ISBN 978-0-694-51187-7.

- Davis, Ossie (1992). Just Like Martin. New York: Simon & Schuster Children's Publishing. ISBN 978-0-671-73202-8.

- Davis, Ossie; Dee, Ruby (1998). With Ossie and Ruby: In This Life Together. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-15396-0.

- Davis, Ossie (2006). Dee, Ruby (ed.). Life Lit by Some Large Vision: Selected Speeches and Writings. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-416-52549-3.

References

- Ossie Davis – Awards IMDB. 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2012

- Ossie Davis Television Credits Archived 2012-04-23 at the Wayback Machine Official Website of Ossie Davis & Ruby Dee. 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2012

- Books Archived 2012-04-23 at the Wayback Machine Official Website of Ossie Davis & Ruby Dee. 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2012

- Dagan, Carmel Oscar-Nominated Actress Ruby Dee Dies at 91. Variety. June 12, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2016

- Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts Archived 2013-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ossie Davis Biography". filmreference. 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- "Davis, Laura Cooper". The Journal News. White Plains, New York. June 9, 2004. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013.

- "Ossie Davis Biography". IMDb. 2008. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- "Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with William Davis" (PDF). HistoryMakers. February 1, 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Heller, Jason (June 6, 2016). "Remembering Muhammad Ali's Trippy, Anti-Cavity Kids' Record". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Severo, Richard; Martin, Douglas (5 February 2005). "Ossie Davis, Actor, Writer and Eloquent Champion of Racial Justice, Is Dead at 87". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts Archived 2013-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee Archived 2012-03-25 at the Wayback Machine Kennedy Center Honors. September 2004. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- 34th Annual Kennedy Center Honors Kennedy Center Honors. 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- "Ossie Davis". The History Makers.

- Davis, Ossie (February 27, 1965). "Malcolm X's Eulogy". The Official Website of Malcolm X. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

- Sheri Stritof; Bob Stritof. "Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee on Open Marriage". About.com. Archived from the original on 2007-02-10. Retrieved 2007-01-11.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Greene, Donna. "Q&A/Ossie Davis; Involved in a Community Beyond Theater", The New York Times, October 25, 1998.

- "Ossie Davis found dead in Miami hotel room". Today. Associated Press. February 9, 2005.

- "Benjamin Banneker: The Man Who Loved the Stars". Baltimore, Maryland: Enoch Pratt Free Library. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2012-09-21.

- Erikson, Hal. "Review Summary: Benjamin Banneker: The Man Who Loved the Stars (1989)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2012-09-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ossie Davis. |

- The official site of Ossie Davis & Ruby Dee

- Life's Essentials with Ruby Dee

- Ossie Davis at the Internet Broadway Database

- Ossie Davis at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Ossie Davis at IMDb

- Ossie Davis at Find a Grave

- Ossie Davis at the TCM Movie Database

- Eulogy of Malcolm X

- Ossie Davis' oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Ossie Davis at Smithsonian Folkways

- Ossie Davis at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Appearances on C-SPAN