Military career of Benedict Arnold, 1777–1779

The military career of Benedict Arnold from 1777 to 1779 was marked by two important events in his career. In July 1777, Arnold was assigned to the Continental Army's Northern Department, where he played pivotal roles in bringing about the failure of British Brigadier Barry St. Leger's siege of Fort Stanwix and the American success in the battles of Saratoga, which fundamentally altered the course of the war.

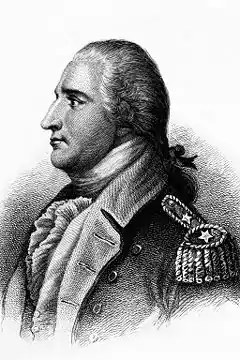

Benedict Arnold V | |

|---|---|

Benedict Arnold Copy of engraving by H.B. Hall after John Trumbull | |

| Born | January 14, 1741 Norwich, Connecticut |

| Died | June 14, 1801 (aged 60) London, England |

| Place of burial | London |

| Service/ | British colonial militia Continental Army British Army |

| Years of service | British colonial militia: 1756, 1775 Continental Army: 1775–1780 British Army: 1780–1781 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands held | Philadelphia West Point |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War, 1777–1779 |

| Awards | Promotion to major general Boot Monument |

| Other work | See Military career of Benedict Arnold, 1781 |

After convalescing following the significant injuries to his leg sustained at Saratoga, Arnold was given military command of Philadelphia after the British withdrawal in 1778. There Arnold became embroiled in political and legal wrangling with enemies in Congress, the army, and the Pennsylvania and Philadelphia governments that undoubtedly contributed to his decision to change sides. In 1779 he began secret negotiations with the British that culminated in a plot to surrender West Point. The plot was exposed in September 1780, and Arnold had no choice but to flee to New York City.

Background

Benedict Arnold was born in 1741 family in the port city of Norwich in the British colony of Connecticut.[1] He was interested in military affairs from an early age, serving briefly (without seeing action) in the colonial militia during the French and Indian War in 1757.[2] He embarked on a career as a businessman, first opening a shop in New Haven, and then engaging in overseas trade. He owned and operated ships, sailing to the West Indies, New France and Europe.[3] When the British Parliament began to impose taxes on its colonies, Arnold's businesses began to be affected by them, and he eventually joined the opposition to those measures.[4] In 1767 he married a local woman, with whom he had three children, one of whom died in infancy.[5][6] She died in 1775, and Arnold left his children under the care of his sister Hannah at his home in New Haven.[7]

Early American Revolutionary War activity

Arnold had distinguished himself early in the war, participating in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775 and then boldly leading a raid on Fort Saint-Jean near Montreal.[7] He then led a small army from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Quebec City on an expedition through the wilderness of present-day Maine, where he was wounded in the climactic Battle of Quebec on December 31, 1775. He then presided over an ineffectual siege of Quebec until April 1776, when he took over the military command of Montreal.[8] He directed the American retreat from there on the arrival of British reinforcements, and his forces formed the rear guard of the retreating Continental Army as it headed south toward Ticonderoga. Arnold then organized the defense of Lake Champlain, and led the Continental Navy fleet that was defeated in the October 1776 Battle of Valcour Island.[9]

During these actions, Arnold made a number of friends and a larger number of enemies within the army power structure and in Congress. He had established decent relationships with George Washington, commander of the army, as well as Philip Schuyler and Horatio Gates, both of whom had command of the army's Northern Department during 1775 and 1776.[10] However, an acrimonious dispute with Moses Hazen, commander of the 2nd Canadian Regiment, boiled over into a court martial of Hazen at Ticonderoga during the summer of 1776. Only action by Gates, then his superior at Ticonderoga, prevented his own arrest on countercharges levelled by Hazen.[11] He had also had disagreements with John Brown and James Easton, two lower-level officers with political connections that resulted in ongoing suggestions of improprieties on his part. Brown was particularly vicious, publishing a handbill that claimed of Arnold, "Money is this man's God, and to get enough of it he would sacrifice his country".[12]

Eastern Department

Defense of Rhode Island

Following the defeat on Lake Champlain, Arnold accompanied Major General Horatio Gates as he led a portion of the army at Ticonderoga south to assist General Washington in the defense of New Jersey.[13] On December 7, 1776, a large British force under Lieutenant General Henry Clinton occupied Newport, Rhode Island.[14] In response Washington ordered Arnold to go back to New England to raise militia and coordinate the defense of Rhode Island. Arnold was made Deputy Commander of the Eastern Department of the Continental Army under Major General Joseph Spencer, and left Washington's camp in Pennsylvania on December 22.[15]

Arnold, who had not seen his family for over a year, spent a week visiting with them in New Haven, during which he successfully urged Washington and Henry Knox, the army's chief of artillery, to raise an artillery regiment for John Lamb and Eleazer Oswald, two Connecticut men who had served with him on the expedition to Quebec.[16] He arrived at Providence on January 12, 1777, to lead the defense against the British at Newport. There were 4,000 Rhode Island militia mobilized, and both the governor and Arnold's commander, General Spencer, were itching to drive the British out of Newport.[14] Arnold developed a plan for driving the British from Newport, but found that the militia were so poorly equipped and supplied that offensive operations were, in his view, ill-advised.[14][17]

— Arnold to Washington, March 12, 1777[18]

In February 1777 Arnold met and seriously courted the daughter of a well known Boston Loyalist, Betsy Deblois, described as the belle of Boston. "The heavenly Miss Deblois" refused his repeated proposals, likely because she was only fifteen.[19] When he returned to Providence he learned that he was one of several officers that had been passed over for promotion to major general by Congress. The reasons for this were largely political in nature, but it is unlikely that his prospects were helped by Horatio Gates' delivery of a petition by John Brown making many accusations against Arnold just one month before Congress took up the matter.[20] Gates was apparently upset that Washington had given the Rhode Island command to Arnold, and now viewed him as a competitor for promotion and choice of assignments.[21]

It was not unusual in military establishments of the time that individuals passed over for promotion were expected to resign, so Arnold on March 12 wrote to Washington, offering his resignation, or alternatively asking for a court of inquiry. Washington refused his offer to resign, and wrote to members of Congress in an attempt to correct the situation, noting that "two or three other very good officers" might be lost if they persisted in making politically motivated promotions.[22] After Washington wrote Arnold explaining to him that the rejection was due to how the Congress had allocated promotions to the states (and Connecticut already had its quota of major generals), Arnold persisted in seeking some sort of inquiry, and complained in a letter to General Gates that "no gentleman who has any regard for his reputation will risk it with a body of men who seem to be governed by whim and caprice" and that he felt "the unmerited injury my countrymen have done me."[23]

Tryon's Danbury raid

After plans were shelved to attack the British at Newport, Arnold left for Philadelphia to meet with the Continental Congress and Washington over his future. He stopped in New Haven to visit his family once again, and assisted his friend Colonel Lamb in hunting down Loyalists in the area.[23] A courier notified him on April 26 that a British force 2,000 strong under Major General William Tryon, the last British governor of New York, had landed at Fairfield, Connecticut. Tryon marched his force inland to Danbury, a major supply depot for the Continental Army. Driving away the few defenders, he ordered the destruction of the stores and a number of properties belonging to Patriot supporters.[24]

Arnold and Major General David Wooster, who had overall command of Connecticut's defense forces and was also in New Haven, hurriedly recruited about 100 volunteers locally. They then headed for Redding, the muster point specified by militia Major General Gold S. Silliman, who oversaw Fairfield County's defenses.[25] Silliman had mustered a force of 500 volunteers from eastern Connecticut.[26] Under Wooster's direction Arnold and his fellow officers moved their small force toward Danbury so they could intercept and harass the British as they returned to their ships. Wooster divided the force, with Arnold and Silliman leading 400 men to the village of Ridgefield, Connecticut to block the British march, while he led 200 men to harass the British rear guard. By 11 am on April 27 Wooster's column had caught up with and engaged Tryon's rear guard. In two brief skirmishes, Wooster was mortally wounded, but the action delayed the British long enough for Arnold and Silliman to establish a crude breastwork just north of Ridgefield.[27] In the ensuing battle, the militia companies put up stiff resistance before they were flanked and driven off.[26] Arnold's horse was shot, and when it went down, his leg was pinned under it. Arnold was very nearly bayoneted by a British soldier, but shot him with a pistol and managed to get away with a minor wound to his left leg.[28] The British camped for the night near Ridgefield, and then proceeded on toward the coast, harassed by militia all the way.[26] Arnold and Silliman rallied their troops, which grew to include Continental Army and artillery units as well as militia units from further afield. Arnold eventually established a fairly strong position on Campo Hill (in present-day Westport, Connecticut) near the beach where the British expected to embark.[29] The British managed to elude his attempt to entrap them, and drove off many of the militia with their field artillery before embarking on their ships and sailing back to New York. During the final skirmishing, Arnold had a second horse shot out under him.[30] When Congress learned of the action on May 2, it finally promoted Arnold to major general, although his seniority of rank was behind those promoted in February.[31]

After the Danbury raid, Arnold continued his journey to Philadelphia, stopping to meet with Washington at Morristown, New Jersey. During this time he learned of the publication of Brown's pamphlet, and insisted to Washington that his name had to be cleared. Arnold's lobbying paid off, and even opponents of the traditional promotion schemes, including John Adams, came to realize that Arnold was being unjustly treated.[32] After a lengthy hearing before the Board of War on May 21, in which Arnold's actions and financial accounts in the Quebec campaign were scrutinized, the board completely exonerated him, issuing a statement that it was satisfied with Arnold's "character and conduct, so cruelly and groundlessly aspersed in Brown's publication."[33] However, it took no steps to restore his seniority.[33]

The seniority issue had annoyed not just Arnold, but also John Stark, Nathanael Greene, John Sullivan, and Henry Knox. Stark resigned his commission as brigadier after Congress offered a major general's commission to a French soldier of fortune, Philippe de Coudray, and the other three complained loudly over the matter.[34][35] Congress passed over his petition for restoration of seniority, and deliberately snubbed him for consultation on the defense of Philadelphia in favor of Pennsylvania native Thomas Mifflin, one of the generals promoted ahead of him.[34] Arnold tendered his resignation to Congress on July 11.[35] However, Washington had written Congress the day before, informing them that a British army under General John Burgoyne had captured Fort Ticonderoga, and recommending in glowing terms that Arnold be sent north to assist in the defense of the Hudson River valley. Given Washington's strong support, Arnold asked that his resignation be shelved, and he left Philadelphia for the north.[36] In a vote on August 8, Congress voted against restoring Arnold's seniority. The next day, it offered a major general's commission to the Marquis de Lafayette, then just nineteen years old.[37]

Stanwix and Saratoga

When Arnold arrived in the Continental Army camp on the upper Hudson River in mid-July, Major General Schuyler was leading the forces there. Schuyler placed Arnold in command of the army's advance guards at Fort Edward. It was during this time that Jane McCrea, the fiancée of a Loyalist fighting with Burgoyne's army, was slain by Burgoyne's Indian auxiliaries. This event was widely retold and embellished with lurid details, and is said to have contributed to Patriot recruiting efforts.[38] In the following weeks, Schuyler's army retreated before Burgoyne's advance, until it reached the Mohawk River south of Stillwater on August 18.[39]

Relief of Fort Stanwix

In early August Schuyler dispatched Arnold and 900 men to relieve the garrison at Fort Stanwix on the upper Mohawk, which had been placed under siege by a British-Indian force led by Brigadier Barry St. Leger.[40] Arnold marched along the Mohawk to Fort Dayton, which he reached on August 20. There he attempted to recruit additional militia to enlarge the relief force, but was unsuccessful; the local militia had suffered grievously in the bloody Battle of Oriskany that ended the first attempt to relieve the siege.[41]

Uncomfortable with the number of troops available to him, Arnold opted for a deception to sow trouble in the besieger's camp outside Fort Stanwix. A number of Loyalists had been arrested near Fort Dayton, including one Hon-Yost Schuyler. Hon-Yost suffered from some form of mental illness which, while looked down on by the Europeans, was seen by many Indians as a touch of the Great Spirit. Arnold convinced Hon-Yost to spread rumors that large numbers of Americans, under the command of "The Dark Eagle", were about to descend on St. Leger's camp.[42] Hon-Yost's good conduct was assured by holding hostage his brother, who was also among the arrested.[43] Arnold's stratagem apparently worked. St. Leger recorded on August 21 that "Arnold was advancing, by rapid and forced marches, with 3,000 men", and the Indians of St. Leger's expedition, who made up the majority of his force, abandoned the siege the next day.[44] As a result, St. Leger lifted the siege and began the journey back to Montreal. Arnold did march to Stanwix, arriving after St. Leger had left; detachments sent by Arnold to chase after him spotted his boats on Lake Oneida.[45][46]

Saratoga

After leaving reinforcements with the Fort Stanwix garrison, Arnold returned to Stillwater, where General Gates had taken over the command from Schuyler. Arnold had learned of Gates' assumption of command while he was at Fort Dayton. He wrote a somewhat perfunctory congratulatory to Gates when he heard of the American victory in the Battle of Bennington, but a somewhat warmer letter he wrote to Schuyler at the same time somehow fell into Gates' hands. Gates provided a snub of sorts when he reported to Congress on the relief of Stanwix and the action at Bennington, and failed to mention Arnold's role; he did specifically mention Stark and Seth Warner, the principal commanders at Bennington, in his dispatch. Washington was more forthcoming with praise, recognizing that "the approach of General Arnold with his detachment" played a key role in the relief of Stanwix.[47]

On his return to Gates' camp, Arnold learned of the Congressional decision to not restore his seniority. He then annoyed Gates by taking on as aides several men who had been on Schuyler's staff, including Henry Brockholst Livingston. The two men also disagreed on strategy: Arnold argued in councils in favor of drawing Burgoyne into battle, while Gates preferred to establish a strong line of defense and wait for Burgoyne's assault.[48] Relations between the men deteriorated further when Gates effectively overrode brigade assignments he had asked Arnold to make, and were not helped by Gates' adjutant, James Wilkinson. Arnold characterized the scheming Wilkinson as a "designing villain"; Wilkinson is reported to have regularly cast aspersions on Arnold and his staff to Gates.[49]

This friction between the two men and their respective camps boiled over after the September 19 Battle of Freeman's Farm. In that battle, Arnold was forceful in wanting to move troops out of the strong American fortifications to head off a flanking maneuver. Gates grudgingly allowed this, and Arnold's troops sent out to counter the British advance precipitated the battle.[50] It has been widely recounted in histories of this battle that General Arnold was on the field, directing some of the action. However, John Luzader, a former park historian at the Saratoga National Historical Park, carefully documents the evolution of this story and believes it is without foundation in contemporary materials, and that Arnold remained at Gates' headquarters, receiving news and dispatching orders through messengers. Arnold biographer James Kirby Martin, however, disagrees with Luzader, arguing that Arnold played a more active role at Freeman's Farm by directing patriot troops into position and possibly leading some charges before being ordered back to headquarters by Gates.

The battle was technically a British victory, as they gained the field of battle. However, they suffered significant casualties that they could ill afford, the American army's strong position was not assaulted, and American casualties were comparatively modest.[51] According to Richard Varick, a former Schuyler aide and no friend of Gates, the general "seemed to be piqued" at the performance of Arnold's division in the battle, and Henry Brockholst Livingston wrote that Arnold was "the life and soul of the troops" and that he had "the confidence and affection of his officers and soldiers."[52] An officer unconnected to either camp commented that Arnold had "won the admiration of the whole army", and that the idea that Gates had squandered an opportunity to inflict a decisive blow on the British was widely held by officers.[52]

The Gates camp then engaged in a series of actions that Arnold perceived to be an attack. James Wilkinson wrote a letter to General Arthur St. Clair in Philadelphia in which he implied not only that Arnold was not involved in the battle, but that he was an impediment to Gates. Gates' official report to Congress notably made no mention of Arnold, Morgan, or other officers involved in leading the action, and specifically mentioned Arnold's nemesis John Brown, who had made an attack against Fort Ticonderoga the day before the battle.[53] A decision by Gates concerning Morgan's unit then caused relationships between Gates and Arnold to break down completely. Morgan's unit had technically been under Gates' command, but it had operated in the battle under Arnold's division and his direction. Gates formally realigned the units to reiterate that Morgan reported to him and not Arnold.[54] The ensuing discussion between Gates and Arnold on September 22 escalated into a shouting match, and ended with Gates relieving Arnold of his command. Arnold requested a pass to rejoin Washington's army, which he was given.[55] However, for unknown reasons, he decided to stay in camp. A common account of a memorial signed by Gates' field commanders encouraging him to stay has no basis in the documentary record;[56] it is known that Brigadier Enoch Poor, who had been critical of Arnold during the court martial at Ticonderoga, and other officers openly considered the idea.[57] This support for Arnold may have played a role in his announcement on September 26 that he was staying in camp even though his differences with Gates had not been resolved.[58]

When General Burgoyne made a reconnaissance in force of the American left on October 7, this began a series of actions that precipitated the Battle of Bemis Heights. According to conventional histories, Gates, now in command of the American left, ordered troops out to meet them.[59] At a critical point in the battle, Arnold, who may have been drinking, left his tent, mounted a horse, and rode off to the battlefield.[60] This chronology is based on reports of the action, most of which were recorded many years later, after Arnold's treason. A letter, brought to light in 2015 and written by an adjutant at Arnold's headquarters, tells a different story, indicating that Arnold requested and received permission from Gates to lead men out into the field.[61]

Rallying what had been his troops in the first battle, Arnold led them in a furious assault against two redoubts on the British right.[60] In this phase of the battle, one of the redoubts was taken, and Arnold's horse and leg were shot. When the horse went down, Arnold's leg was shattered in several places.[62] The battle was a resounding victory for the Americans. Burgoyne began a retreat, but was quickly surrounded by militia companies that streamed into the area, and surrendered on October 17.[63]

Gates could not ignore Arnold's role in the second battle, since the news of Arnold's injuries traveled quickly. He limited acknowledgement of Arnold's participation to the leading of a "gallant" assault on the redoubt.[64] Much to Arnold's disgust, Gates himself was lauded by Congress and awarded a gold medal; Burgoyne, on the other hand, claimed that Arnold was responsible for his defeat.[64] Congress did finally vote to restore Arnold's seniority. However, Arnold interpreted the manner in which they did so as an act of sympathy for his wounds, and not an apology or recognition that they were righting a wrong.[65]

Arnold's contribution to the victory at Saratoga is commemorated by the Boot Monument in Saratoga National Historical Park. Donated by Civil War General John Watts de Peyster, it shows a boot with spurs and the stars of a major general. It stands at the spot where Arnold was shot on October 7 charging Breymann's redoubt, and is dedicated to "the most brilliant soldier of the Continental Army".[66]

Philadelphia command

Following Saratoga, Arnold was taken to an Albany hospital to recover from the wounds he had received in the battle. His left leg was ruined, but Arnold would not allow it to be amputated. Several agonizing months of recovery left it 2 inches (5 cm) shorter than the right.[67] After several months in Albany, he was transferred to Middletown, Connecticut, where he could be nearer his children. While recuperating there, he sent two more entreaties to Betsy DeBlois; the first she answered with a firm refusal, and the second went unanswered.[68] When he was well enough to travel, he departed Connecticut for Valley Forge, where he arrived on May 20, 1778, to the boisterous applause of troops he had commanded at Saratoga.[69] There he participated, with many other soldiers, in the first recorded Oath of Allegiance as a sign of loyalty to the United States.[70]

As the British planned to withdraw from Philadelphia in June 1778 Washington appointed Arnold to take military command of the city after the British retreat.[71] Even before the Americans reoccupied Philadelphia, Arnold began scheming to capitalize financially on the change in power there, engaging in a variety of business deals designed to profit from war-related supply movements and benefiting from the protection of his authority. While these schemes were not necessarily illegal, the ethics involved were seen as highly dubious at the time. Some of his schemes were frustrated by the actions of highly partisan Patriots, including the politically powerful Joseph Reed. These business dealings required capital, which Arnold often borrowed. Arnold furthered his debts by living extravagantly, occupying the Penn mansion and throwing parties for high society. Complicating the situation was the fact that Arnold was administratively trapped between the relatively powerful Pennsylvania government and the Congress, which was often forced to bow to the populous state's demands in order to achieve its aims.[72] Reed and others amassed a series of irregularities in Arnold's official actions, and open war of words erupted between Arnold and Reed and his supporters. By February 1779 a variety of charges had been publicly made that he was abusing his power.[73] He demanded a full court martial, writing to Washington in May, "Having become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet [such] ungrateful returns".[74] The court martial was postponed (it would not be held until December 1779), once more leaving Arnold frustrated and angry at the Congress for its inaction.[75]

During the summer of 1778 Arnold met Peggy Shippen, the 18-year-old daughter of Judge Edward Shippen, a Loyalist sympathizer who had done business with the British while they occupied the city.[76] Peggy had been courted by British Major John André during the British occupation of Philadelphia.[77] Peggy and Arnold married on April 8, 1779.[78] Peggy and her circle of friends had found methods of staying in contact with paramours across the battle lines, in spite of military bans on communication with the enemy.[79] Some of this communication was effected through the services of Joseph Stansbury, a Philadelphia merchant.[80]

Sometime early in May 1779, Arnold met with Stansbury. Stansbury, whose testimony before a British commission apparently erroneously placed the date in June, said that, after meeting with Arnold, "I went secretly to New York with a tender of [Arnold's] services to Sir Henry Clinton."[81] This was the start of a series of negotiations between Arnold and Sir Henry's chief spy, the very same Major André that had courted Peggy.[82] Between July and October 1779, the two negotiated over terms of Arnold's change to the British side, while Arnold provided the British with information on troop locations and strengths, as well as the locations of supply depots.[83]

Court martial

The court martial to consider the charges against Arnold began meeting in December 1779. In spite of the fact that a number of members of the panel of judges were men ill-disposed to Arnold over actions and disputes earlier in the war, Arnold was cleared of all but two minor charges on January 26, 1780.[84] Arnold worked over the next few months to publicize this fact; however, in early April, just one week after Washington congratulated Arnold on the March 19 birth of his son, Edward Shippen Arnold, Washington published a formal rebuke of Arnold's behavior.[85]

The Commander-in-Chief would have been much happier in an occasion of bestowing commendations on an officer who had rendered such distinguished services to his country as Major General Arnold; but in the present case, a sense of duty and a regard to candor oblige him to declare that he considers his conduct [in the convicted actions] as imprudent and improper.

Shortly after Washington's rebuke, a Congressional inquiry into his expenditures concluded that Arnold had failed to fully account for his expenditures incurred during the Quebec invasion. It concluded that he owed the Congress some £1,000, largely because he was unable to document his expenses. A significant number of the necessary documents were lost during the retreat from Quebec; once again frustrated by Congress, Arnold resigned his military command of Philadelphia in late April.[87]

Later action

Following Arnold's resignation from the Philadelphia post, he was for a time without a command. After reopening the stalled negotiations with André, he obtained command of West Point in August 1780, and set about weakening its defenses. Following a meeting with André in September, the plot was exposed when André was captured attempting to cross the lines into New York City while carrying incriminating documents.[88] Arnold fled to New York, and began military service as a Brigadier in the British Army in 1781, leading a raiding expedition against supply depots and economic targets in Virginia, and then a raid against New London, Connecticut.[89] With the end of major hostilities following the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, Arnold and his family left for England at the end of 1781, on a ship that also carried Lord Cornwallis.[90]

Despite repeated attempts to gain command positions in the British Army or with the British East India Company, he saw no further military duty. He resumed business activities, engaging in trade while based at first in Saint John, New Brunswick and then London. He died in London in 1801.[91]

Notes

- Brandt (1994), p. 4–6

- Flexner (1953), p. 8

- Flexner (1953), p. 13

- Randall (1990), p. 49–53

- Brandt (1994), p. 14

- Randall (1990), p. 62

- Randall (1990), pp. 78–132

- Randall (1990), pp. 131–228

- Randall (1990), pp. 228–320

- Randall (1990), pp. 318–323

- Randall (1990), pp. 262–264

- Howe (1848), pp. 4–6

- Randall (1990), pp. 321–323

- Randall (1990), p. 325

- Martin (1997), p. 292

- Randall (1990), p. 324

- Martin (1997), p. 301

- Randall (1990), p. 329

- Brandt (1994), p. 116

- Martin (1997), p. 306

- Palmer (2006), p. 189

- Brandt (1994), p. 118

- Randall (1990), p. 331

- Randall (1990), p. 332

- Bailey (1896), p. 61

- Ward (1952), p. 494

- Bailey (1896), pp. 76-78

- Bailey (1896), p. 78

- Bailey (1896), p. 79

- Ward (1952), p. 495

- Randall (1990), p. 334

- Randall (1990), p. 336

- Randall (1990), p. 338

- Martin (1997), p. 333

- Randall (1990), p. 339

- Randall (1990), p. 342

- Randall (1990), p. 343

- Martin (1997), pp. 350–352

- Martin (1997), p. 353

- Martin (1997), pp. 362–363

- Martin (1997), pp. 364–365

- Pancake (1977), p. 145

- Nickerson (1967), p. 273

- Martin (1997), p. 366

- Martin (1997), pp. 366–367

- Watt (2002), pp. 260–261

- Martin (1997), pp. 367–368

- Martin (1997), p. 370

- Martin (1997), p. 371

- Martin (1997), pp. 387–391

- Ketchum (1997), p. 368

- Martin (1997), p. 384

- Martin (1997), pp. 385–386

- Martin (1997), p. 385

- Ketchum (1997), p. 386

- Luzader (2008), p. 271

- Martin (1997), p. 390

- Martin (1997), p. 391

- Ketchum (1997), pp. 391–394

- Martin (1997), pp. 396–398

- Williams, Stephen (March 26, 2016). "Letters change view of Benedict Arnold, Gen. Gates". The Daily Gazette. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- Martin (1997), p. 400

- Martin (1997), p. 405

- Palmer (2006), p. 255

- Palmer (2006), p. 256

- Saratoga National Historical Park Tour Stop 7

- Brandt (1994), pp. 141–143

- Brandt (1994), p. 144

- Brandt (1994), pp. 145–146

- Brandt (1994), p. 147

- Brandt (1994), p. 146

- Brandt (1994), pp. 148–153

- Brandt (1994), pp. 160–161

- Martin, p. 428

- Brandt (1994), pp. 169–170

- Randall (1990), p. 420

- Edward Shippen biography

- Randall (1990), p. 448

- Randall (1990), p. 455

- Randall (1990), p. 456

- Randall (1990), pp. 456–457

- Martin (1997), p. 428

- Randall (1990), pp. 474–477

- Randall (1990), pp. 486–492

- Randall (1990), pp. 492–494

- Randall (1990), p. 494

- Randall (1990), pp. 497–499

- Randall (1990), pp. 452–582

- Arnold, pp. 342–348

- Arnold, p. 358

- Randall (1990), pp. 592–612

References

- Arnold, Isaac Newton (1905). The life of Benedict Arnold: his patriotism and his treason. Chicago: A. C. McClurg. OCLC 9993726.

- Bailey, James Montgomery; Hill, Susan Benedict (1896). History of Danbury, Conn., 1684–1896. New York: Burr Print. House. OCLC 1207718.

- Brandt, Clare (1994). The Man in the Mirror: A Life of Benedict Arnold. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-40106-7. OCLC 123244909.

- Flexner, James Thomas (1953). The traitor and the spy: Benedict Arnold and John André. New York: Harcourt Brace. OCLC 426158.

- Howe, Archibald (1908). Colonel John Brown, of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, the Brave Accuser of Benedict Arnold. Boston: W. B. Clarke. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- Ketchum, Richard M (1997). Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6123-9. OCLC 41397623. (Paperback ISBN 0-8050-6123-1)

- Luzader, John F (2008). Saratoga: A Military History of the Decisive Campaign of the American Revolution. New York: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-44-9. OCLC 464591984.

- Martin, James Kirby (1997). Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero (An American Warrior Reconsidered). New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5560-7. OCLC 36343341.

- Nickerson, Hoffman (1967) [1928]. The Turning Point of the Revolution. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat. OCLC 549809.

- Palmer, Dave Richard (2006). George Washington and Benedict Arnold: a tale of two patriots. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59698-020-4. OCLC 69027634.

- Pancake, John S (1977). 1777: The Year of the Hangman. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5112-0. OCLC 2680804.

- Randall, Willard Sterne (1990). Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 1-55710-034-9. OCLC 185605660.

- Ward, Christopher (1952). The War of the Revolution. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 214962727.

- Watt, Gavin K; Morrison, James F (2002). Rebellion in the Mohawk Valley: The St. Leger Expedition of 1777. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-376-3. OCLC 49305965.

- "Saratoga National Historical Park - Tour Stop 7". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- "Edward Shippen (1729–1806)". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on February 4, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-18.