Mounseer Nongtongpaw

Mounseer Nongtongpaw is an 1808 poem thought to have been written by the Romantic writer Mary Shelley as a child. The poem is an expansion of the entertainer Charles Dibdin's song of the same name and was published as part of eighteenth-century philosopher William Godwin's Juvenile Library. A series of comic stanzas on French and English stereotypes, Mounseer Nongtongpaw pillories John Bull for his inability to understand French. It was illustrated by Godwin's friend William Mulready.

Publication details

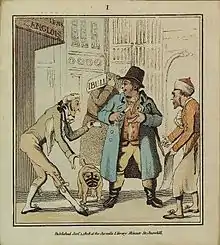

Mounseer Nongtongpaw was originally published by William Godwin's publishing firm, M. J. Godwin, in 1808 as part of its Juvenile Library series.[1] English editions have been located for 1811, 1812, 1823, and 1830 and Philadelphia editions have been located for 1814 and c. 1824.[2] The original edition was illustrated by a protégé of Godwin, William Mulready.[3] Shelley biographer Emily Sunstein speculates that some of the verses may have been written to match illustrations that were already designed.[4] The copper plate engravings are reproduced in Peter and Iona Opie's Nursery Companion.

Structure and plot

Mounseer Nongtongpaw is based on a popular 1796 song of the same name by the entertainer Charles Dibdin.[5] Dibdin's original song mocks English and French stereotypes in five eight-line stanzas, particularly "John Bull's" refusal to learn French. John Bull makes numerous inquiries to which he always receives the same response: "Monsieur, je vous n'entends pas" ("Monsieur, I don't understand you"), which he mistakenly interprets as "Mounseer Nongtongpaw". He comes to believe that the Palais Royal, Versailles, and a beautiful woman—the sights he sees while touring France—belong to this mysterious personage. When he comes upon a funeral and receives the same response, he concludes that all of Nongtongpaw's wealth could not save him from death.[1] Mounseer Nongtongpaw expands Dibdin's comic verses, adding more events to the narrative in shorter four-line stanzas, such as inquiries about a tavern feast, a shepherd's flock, a coach and four, and a hot-air balloon:[6]

[John Bull] ask'd who gave so fine a feast,

As fine as e'er he saw;

The landlord, shrugging at his guest,

Said "Je vous n'entends pas."

"Oh! MOUNSEER NONGTONGPAW!" said he:

"Well, he's a wealthy man,

"And seems dispos'd, from all I see,

"To do what good he can.

"A table set in such a style

"Holds forth a welcome sign," —

And added with an eager smile,

"With NONGTONGPAW I'll dine."<ref>Moskal, 402.</ref>

Attribution

Mounseer Nongtongpaw was first attributed to the ten-and-a-half-year-old Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley) in A Nursery Companion (1980) by Peter and Iona Opie. Don Locke supported this view in his biography of William Godwin, Mary's father, that same year.[7] The attribution rested on a 1960 advertisement by a book dealer, which printed part of a 2 January 1808 letter from William Godwin to an unknown correspondent:[8]

I therefore enclose two scribbles with which I would not otherwise have troubled you....That in small writing is the production of my daughter in her eleventh year, and is strictly modelled, as far as her infant talent would allow, on Dibdin's song....The whole object is to keep up the joke of Nong Tong Paw being constantly taken for the greatest man in France.[9]

"Dibdin's song" refers to the popular song by Charles Dibdin on which the poem is based.[5] The Opies wrote that "the presumption must be that the verses Godwin printed were those by his daughter".[10] In the 1831 introduction to Frankenstein, Shelley described her early childhood writing as that of "a close imitator—rather doing what others had done, than putting down the suggestions of my own mind".[11]

However, after the rediscovery of the entire letter, doubts emerged regarding this attribution:

Dear Sir,

In the midst of our short conversation of yesterday, & still more pleasant than short, you expressed a wish to receive a sketch in prose of the thing we desired. I am sure your kindness renders it a duty incumbent on me in return, to afford you every facility in my power. I therefore inclose two scribbles with which I would not otherwise have troubled you. That in small writing is the production of my daughter in her eleventh year, & is strictly modelled, as ar as [sic] her infant talents would allow, on Dibdin's song. This may answer the purpose of a prose sketch. The other is written by a young man of twenty. It is rather unintelligible: but the

twofirst two stanzas may afford you a hint respecting the first two designs.The more what you shall favour us with shall purely be your own, the more exquisite I am well satisfied it will be found. The whole object is to keep up the joke of Nong Tong Paw being constantly taken for the greatest man in France.

Believe me, with a thousand thanks,

My dear sir,

Very sincerely yours

W GodwinJan. 2, 1808.

May we send to you at ten or eleven to-morrow morning?

If you should have any thing to communicate, & should address it to Mr. Hooley, 41, Skinner Street, Snow Hill, it will reach me in safety.[12]

The complete letter suggests that the "small writing" was a prose piece, although Sunstein, the former owner of the letter (which is now held by The Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle), argues that the wording is open to interpretation.[13] She claims that "read in its entirely, [the letter] indicates that Mary Godwin wrote the initial revised text for Nongtongpaw, but not the final version".[14] She argues "that Mary Godwin's revision was usable for a 'prose sketch' does not necessarily mean that she wrote it in prose".[15]

According to Jeanne Moskal, one of the editors of the most recent definitive edition of Mary Shelley's works, "It can be deduced from the letter, and corroborated by other circumstantial evidence uncovered by Sunstein, that the correspondent had been invited to write a new version of Dibdin's song and that the correspondent and the composer of the 1808 text were therefore one and the same."[16]

Significance

Mounseer Nongtongpaw represents the beginning of Mary Shelley's collaborative writing career, although it is no longer possible to reconstruct her actual contributions. Her sketch was given to the author of the published work as a way to inspire him. What precisely he drew from that text is, however, unknown.[17]

Notes

- Sunstein, 20.

- Moskal, 399, note 1. Moskal only searched for editions published during Mary Shelley's lifetime. She mentions that there are some significant variations among these editions but does not list them.

- Moskal, 399, note 1; Sunstein, 19; Opie, 128.

- Sunstein, 21.

- Moskal, 397; Sunstein, 20.

- Sunstein, 20, 22.

- Opie, 127–28; Locke, 215.

- Moskal, 397; Sunstein, 19.

- Qtd. in Moskal, 397; Qtd. in Opie, 128.

- Opie, 128.

- Qtd. in Moskal, 397.

- Qtd. in Sunstein, 19–20.

- Moskal, 397 and 399, note 6.

- Sunstein, 19.

- Sunstein, 20–21.

- Moskal, 397-98. Sunstein points to a meeting between Godwin and a "J Taylor" as well as Godwin's publication of another of Taylor's works as evidence of his involvement (Sunstein 21).

- Moskal, 398; Sunstein, 22.

Bibliography

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- —. Mounseer Nongtongpaw. New York Public Library Digital Gallery. New York Public Library. 31 July 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- Locke, Don. A Fantasy of Reason: The Life and Thought of William Godwin. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980. ISBN 0-7100-0387-0.

- Moskal, Jeanne. "Appendix 2: 'Mounseer Nongtongpaw': Verses formerly attributed to Mary Shelley". Travel Writing: The Novels and Selected Works of Mary Shelley. Vol. 8. Ed. Jeanne Moskal. London: William Pickering, 1996. ISBN 1-85196-076-7.

- Opie, Iona and Peter. A Nursery Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-19-212213-4.

- Sunstein, Emily W. "A William Godwin Letter, and Young Mary Godwin's Part in Mounseer Nongongpaw". Keats-Shelley Journal 45 (1996): 19–22.