Muriqui, Mangaratiba

Muriqui (also known as Vila Muriqui) is a district[4] of the municipality of Mangaratiba, located within the Greater Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It is part of the Green Coast. Highway BR-101 passes through the district.

Muriqui

Vila Muriqui | |

|---|---|

District | |

Panoramic view of Muriqui | |

Location in Mangaratiba | |

Muriqui Location in Rio de Janeiro | |

| Coordinates: 22°55′33.8″S 43°56′52.2″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Municipality/City | |

| Established | c. 1597 |

| Incorporated (district) | December 1, 1949 |

| Named for | Muriqui spider monkeys |

| Area | |

| • Total | 38.0268 km2 (14.6822 sq mi) |

| [lower-alpha 1] | |

| Elevation [2] (Posto de Saúde Muriqui) | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 1,226 m (4,022 ft) |

| Lowest elevation [2] (Praia de Muriqui) | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • Total | 10,241 |

| • Density | 269.31/km2 (697.5/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | Vila-muriquiense; muriquiense |

| Sex ratio (2010) | |

| • Female | 5,225 (51.02%) |

| • Male | 5,016 (48.98%) |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (BRT) |

| Website | www |

The district has a patron saint, the Blessed Virgin Mary (Portuguese: Nossa Senhora das Graças).[5] Since the 1950s, the local parish has celebrated annually on the 27th of November, the date Catherine Labouré reportedly had a vision of her in 1830.[6]

Etymology

The district was named after muriquis, a genus of spider monkeys.[7] The name "muriqui" itself comes from a corruption of the word myraqui, of the Tupi language, with the alternates buriqui, barigui and baregui.[8] According to Alcides Pissinatti, in "Management of Muriquis in Captivity" (2005):[9]

Its approximate meaning is "people that swing as they come and go" and it refers particularly to the large, pale brown monkeys that inhabit forests along Brazil's Atlantic coast, initially assigned the scientific name of Ateles hypoxanthus by Wied-Neuwied (1958).

However, according to von Martius' glossary, the word comes from the Tupi words jemoroo ("to nourish"; muru, "nutrient") and aiké (a contraction of aikobê: "to have", "to exist").[10]

History

Colonial era

Prior to 1567, all land that now belongs to Mangaratiba – including modern-day Muriqui – was part of the freguesia of Angra dos Reis, under the Captaincy of São Vicente. After that date, those lands became part of the (Royal) Captaincy of Rio de Janeiro.[11] In 1568, the colonization of the region of modern-day Mangaratiba begins through the distribution of land to the Sá family.[12]

At some point before 1598 – the year Francisco de Mendonça e Vasconcelos came to Rio de Janeiro to take office as governor – Salvador Correia de Sá finished building a new engenho (the fifth sugarcane mill of Rio de Janeiro).[13] As per the recounting of Anthony Knivet:[14]

[...] the same yeere (1598) there came Francisco de mondunsa de vesconsales (Francisco de Mendonça e Vasconcelos) for Governour to my Masters place, that day the Hulke which the new Governour was in, came to the mouth of the Haven, the Governour Salvador Corea de Sasa (Salvador Correia de Sá) was at a Sugar-mil that he had newly finished.

According to Vieira de Mello, this engenho was located in Itacuruçá,[13] the district which Muriqui was part of until the middle of the 20th century, and thus became known as "Engenho of Itacuruçá" (Portuguese: Engenho de Itacuruçá). Additionally, Mirian Bondim claims that this engenho was located in the same place as modern-day Muriqui,[15] and it is referred to by the Mangaratiba town hall as the first construction in Mangaratiba land.[16]

On 8 June 1652, D. Suzana Peixoto and her husband, Dom José Rendon[lower-alpha 2] de Quebedo, exchanged an engenho they owned in Irajá, known as "Engenho Fumaça", for the Engenho of Itacuruçá and some farms in Mangaratiba. Prior to this exchange, the governor of Rio de Janeiro Salvador Correia de Sá e Benevides (son of Martim Correia de Sá and grandson of Salvador Correia de Sá)[17] owned the Engenho of Itacuruçá.[15][18][19]

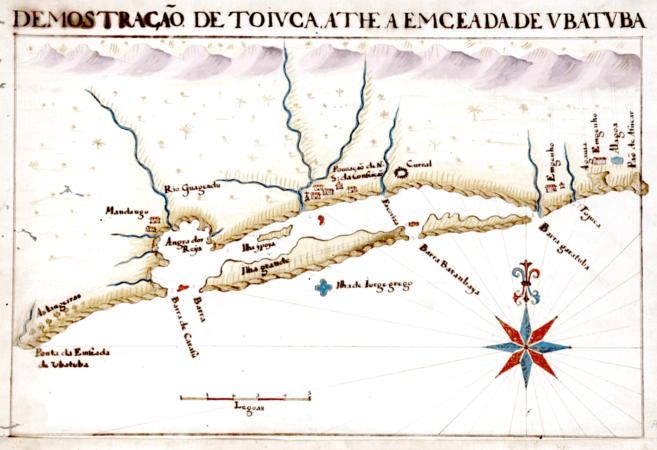

Map of a part of the state of Rio de Janeiro, c. 1666, making no mention of Muriqui.

Map of a part of the state of Rio de Janeiro, c. 1666, making no mention of Muriqui..png.webp) A 1767 map portraying a settlement in Muriqui.

A 1767 map portraying a settlement in Muriqui.

Late modern period

As a part of a series of expansions to the Central Railway of Brazil (Portuguese: Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil), on 7 November 1914, the Muriqui train station was inaugurated.[7]

On 1 December 1949, via a legislative decree, the district of vila de Muriqui is delimited on land previously belonging to the district of Itacuruçá, and annexed to the municipality of Mangaratiba.[20]

Population

| Population pyramid 2010[1] | ||||

| % | Males | Age | Females | % |

| 0.19 | 85+ | 0.43 | ||

| 0.47 | 80–84 | 0.61 | ||

| 0.69 | 75–79 | 0.87 | ||

| 1.29 | 70–74 | 1.35 | ||

| 1.98 | 65–69 | 1.79 | ||

| 2.42 | 60–64 | 2.64 | ||

| 2.50 | 55–59 | 2.74 | ||

| 3.23 | 50–54 | 3.41 | ||

| 3.13 | 45–49 | 3.82 | ||

| 3.42 | 40–44 | 3.46 | ||

| 3.50 | 35–39 | 3.91 | ||

| 3.93 | 30–34 | 3.89 | ||

| 3.67 | 25–29 | 3.97 | ||

| 3.68 | 20–24 | 3.40 | ||

| 3.71 | 15–19 | 4.22 | ||

| 4.82 | 10–14 | 3.97 | ||

| 3.36 | 5–9 | 3.48 | ||

| 2.98 | 0–4 | 3.09 | ||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 983 | — |

| 1960 | 1,885 | +91.8% |

| 1970 | 2,366 | +25.5% |

| 1980 | 3,380 | +42.9% |

| 1991 | 4,345 | +28.6% |

| 2000 | 6,095 | +40.3% |

| 2010 | 10,241 | +68.0% |

| Note: The 1940's census contains no reference to Vila Muriqui, as Muriqui only officially became a district in 1949. Source: IBGE | ||

Administration

Being a district of the larger municipality of Mangaratiba, Muriqui is subject to the administration of Mangaratiba's prefecture – i.e. its mayor and municipal government. However, a subprefecture dedicated exclusively to Muriqui exists.

The following is a list of heads ("subprefeitos") of the subprefecture of Muriqui:

| Name | Nominated | Exonerated | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demócrito Reginaldo | 1 August 2011[21] | ? | ? |

| Demócrito Reginaldo | 1 February 2013[22] | 1 May 2015[23] | 2 years and 3 months |

| Antônio Marcos de Moura | 1 February 2017[24] | 1 July 2018[25] | 1 year and 5 months |

| Adilson dos Santos | 1 August 2018[26] | ? | ? |

| Fabrícia Guerhardt | 20 November 2018[27] | 1 April 2019[28] | 4 months and 12 days |

| Adilson dos Santos | 1 April 2019[28] | 2 January 2020[29] | 9 months and 1 day |

Fauna and Flora

Muriqui is surrounded mostly by Atlantic Forest, which heavily influences its fauna and flora.[3][30]

The southern muriqui (Brachyteles arachnoides), after which the district is named

The southern muriqui (Brachyteles arachnoides), after which the district is named

.jpg.webp) Atlantic ghost crab (Ocypode albicans), known as "maria farinha" (lit. "flour Mary")

Atlantic ghost crab (Ocypode albicans), known as "maria farinha" (lit. "flour Mary") Black mangrove (Avicennia germinans), known as "sereíba"

Black mangrove (Avicennia germinans), known as "sereíba"

Hydrography

Beaches

Muriqui has direct access to the Atlantic Ocean through the Muriqui beach (Portuguese: Praia de Muriqui), located to the west of Sepetiba Bay (Portuguese: Baía de Sepetiba). In terms of balneability, the Muriqui beach has been mostly deemed improper for bathing,[31] although there have been recent efforts in an attempt to clean Mangaratiba rivers and beaches.[32]

Culture

Folklore

Muriqui has its own folklore, limited to the region, and separate from the national-level folklore.

The story of the "Vieira Wind" (Portuguese: Vento Vieira) is part of the oral tradition of the district. The tale is usually related to the high-speed winds in the area during winter (roughly in the period from the end of August to the start of September).[38][39]

According to the Brazilian Archaeology Institute (Portuguese: Instituto de Arqueologia Brasileira, shortened IAB), there are two different versions of the story.[6] The first and more common one, which has been retold by Mangaratiba's official culture manager Fundação Mario Peixoto,[40] was described by local newspaper Jornal Litoral in 2015 as follows:[41]

Entre Agosto e Setembro existe um vento forte que os pioneiros habitantes chamaram de Vieira, que segundo a lenda, este morador de Muriqui, pouco antes de morrer, pediu para ser enterrado nas belas montanhas. E quando o mesmo faleceu, os amigos levaram o corpo no caixão para enterrá-lo sem ser nas montanhas. No momento em que vão colocá-lo na sepultura, começou a ventar muito forte, e os amigos com medo, deixaram o caixão e foram para suas casas. No dia seguinte, ao parar o vento voltaram para acabar o enterro, e lá chegando encontraram o caixão vazio. A partir daquele dia todos acreditaram que o vento havia levado o corpo de "VIEIRA" para as montanhas e como não foi enterrado, volta todos os anos para visitar Muriqui, local que ele muito gostava. |

Between August and September, there is a very strong wind that the inhabitant pioneers called Vieira. According to the lore, this Muriqui resident, on his deathbed, asked to be buried in the beautiful mountains. When he died, his friends took the body in a coffin to be buried, but not on the mountains. In the middle of the burial, strong winds started blowing, so the friends left the coffin and went to their homes, in fear. The next day, after the wind had stopped, they went back to the burial site to find an empty coffin. From that day on, everyone believed that the wind had taken "VIEIRA"'s body to the mountains and, as he wasn't buried, he comes back every year to visit Muriqui, a place he much liked. |

The second version, arguably more grounded in reality, although less common, is as follows:[6]

Um corpo estava sendo velado quando, lá pela madrugada, veio uma ventania tão forte que derrubou o caixão de cima da mesa. O morto, que se chamava Vieira, rolou pelo chão. Duro que nem pedra pesava mais que vivo. Foi uma dificuldade para colocá-lo no caixão. A partir desse dia, apelidaram o vento de "Vieira". |

A body was lying in repose when, at dawn, strong winds started blowing and knocked the coffin on the floor. The deceased, whose name was Vieira, tumbled on the floor. Hard as a rock, he weighed more than the living. It was hard to put him in the coffin. From this day forward, the wind was nicknamed "Vieira". |

Art

Muriqui is home to an art installation by Japanese artist Mariko Mori called Ring: One With Nature, inaugurated atop the Bride's Veil (Portuguese: Véu da Noiva) waterfall in August 2016 to celebrate the 2016 Summer Olympics.[42] The piece is an acrylic ring that changes in color depending on the position of the sun, and is meant as a representation of a sixth Olympic ring. It measures about 3 metres (9.8 ft) in diameter and weighs around 2 tonnes (4,400 lb).[43][44]

View of the art installation from atop the Bride's Veil waterfall.

View of the art installation from atop the Bride's Veil waterfall. View of the art installation from the base of the waterfall.

View of the art installation from the base of the waterfall.

Cuisine

Muriqui's most well known delicacy is the cocada (known as Cocada de Muriqui), deemed to be one of the famous sweets of the Mangaratiba cuisine.[45] According to Fabrini dos Santos, a SEBRAE consultant, the cocadas are distinctive enough that they could, at some point, be granted a geographical indication.[46] The district's cocada has existed at least since the construction of the BR-101 highway, and has been sold on its shoulders ever since.[47]

The coconut-based dessert has had such a cultural impact that, in March 2018, the "Cocada Party of Muriqui" (Portuguese: Festa da Cocada do Distrito de Muriqui) was added to the municipality's official event calendar, to be celebrated annually on the last weekend of the month of July.[47]

Notes

- Value given for area is not exact; it was calculated by using the known values for population and population density.

- Both 'Rendon' and 'Rendom' spellings of the surname can be found.

References

- "IBGE | Censo 2010 | Sinopse por Setores". IBGE. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "Modelo Digital de Elevação - MDE". IBGE. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "Plano de Manejo da Área de Proteção Ambiental de Mangaratiba". Rio de Janeiro: INEA. 2015-09-11. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- "Muriqui | Prefeitura de Mangaratiba". Archived from the original on 2020-01-12. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- "Festa da padroeira de Muriqui, movimenta fim de semana" [Celebration of Muriqui's patron saint drives weekend]. Jornal Litoral (in Portuguese) (5th ed.). Mangaratiba. December 2015. p. 10. Retrieved 2020-12-18 – via Issuu.

- "Levantamento do Patrimônio Cultural Imaterial" [Research of the Intangible Cultural Heritage]. Brazilian Archaeology Institute. Programa de Pesquisas Arqueológicas, de Educação Patrimonial, Levantamento do Patrimônio Cultural Imaterial e Estudos de Elementos de Arquitetura Histórica na Estrada RJ-149 – Rio Claro-Mangaratiba – Estrada do Imperador (in Portuguese).

- Rodriguez, Helio Suêvo (2004). As Formações das Estradas de Ferro no Rio de Janeiro: O Resgate da sua Memória [The Formation of Railroads in Rio de Janeiro: The Rescue of their Memory] (in Portuguese). Memória do Trem. p. 72. ISBN 85-86094-07-2.

- Sampaio, Teodoro (1987) [First published 1901]. O Tupi na Geografia Nacional [The Tupi on National Geography]. Brasiliana Eletrônica da UFRJ (in Portuguese). 380. Introduction and notes by Frederico G. Edelweiss (5th ed.). Companhia Editora Nacional. p. 209. ISBN 85-04-00212-8. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

- Pissinatti, Alcides (December 2005). "Management of Muriquis (Brachyteles, primates) in Captivity". Neotropical Primates. IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group. 13 (Supplement): 93. doi:10.1896/ci.cabs.2005.np.13.suppl (inactive 2021-01-13). ISSN 1413-4705. Retrieved 2020-02-12.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- von Martius, Karl Friedrich Philipp (1867). Beiträge zur Ethnographie und Sprachenkunde Amerika's zumal Brasiliens. University of São Paulo. 2. Leipzig: Friedrich Fleisher. p. 516.

- "Plano Municipal de Educação - Documento Base" (PDF). Ministério Público do Rio de Janeiro (in Portuguese). 2015. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- Bondim, Mirian. "História". Prefeitura de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- Mello, Carl Egbert H. Vieira de (1996). O Rio de Janeiro no Brasil Quinhentista (in Portuguese). São Paulo. pp. 153–155. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- Knivet, Anthony (1906). Purchas, Samuel (ed.). Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes. Biblioteca Digital Curt Nimuendajú. XVI. p. 234. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- "Faça as malas e venha para cá!" [Pack up and come here!]. Prefeitura de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- Bicalho, Maria Fernanda (2013). "Redesenhando fronteiras, ampliando jurisdições: O Rio de Janeiro no período filipino" (PDF). Associação Nacional de História (in Portuguese). Natal. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- Leme, Pedro Taques de Almeida Paes (1869). Nobiliarquia Paulistana: Genealogia das Principaes Famílias de S. Paulo. Biblioteca Digital de Literatura de Países Lusófonos (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro. pp. 187–188 (PDF pp. 856–857). Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- Leme, Luiz Gonzaga da Silva (1905). Genealogia Paulistana. Internet Archive. 9º. São Paulo. pp. 24–25. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- "IBGE | Cidades@ | Rio de Janeiro | Mangaratiba | História & Fotos". IBGE. Archived from the original on 2018-06-26. Retrieved 2020-02-10.

- "Atos da Prefeitura" (PDF). Boletim Informativo Oficial do Município de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese) (329): 10. 2012-01-12. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Atos da Prefeitura" (PDF). Boletim Informativo Oficial do Município de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese) (399 - Suplemento Especial): 32. 2013-06-20. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Atos da Prefeitura" (PDF). Diário Oficial do Município de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese) (519): 5. 2015-06-03. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Atos da Prefeitura" (PDF). Diário Oficial do Município de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese) (686): 13. 2017-04-07. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Atos da Prefeitura" (PDF). Diário Oficial do Município de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese) (838): 82. 2018-07-31. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Atos da Prefeitura" (PDF). Diário Oficial do Município de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese) (848): 36. 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Atos da Prefeitura" (PDF). Diário Oficial do Município de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese) (880): 20. 2018-12-18. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "Atos da Prefeitura" (PDF). Diário Oficial do Município de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese) (917): 5. 2019-04-26. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "Atos da Prefeitura" (PDF). Diário Oficial do Município de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese) (1069): 20. 2020-01-29. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- Barreiros, Humberto de Souza (June 1980). "Excursão a Vila Muriqui" [Excursion to Vila Muriqui]. Rodriguésia (in Portuguese). Vol. 32 no. 53. Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden. pp. 319–320. ISSN 2175-7860.

- "Três em dez praias são impróprias para banho no Brasil; pesquise" [Three in ten beaches are unsuited for bathing in Brazil; look up]. Folha de S.Paulo (in Portuguese). 2017-02-05. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- Neves, Rafaela (2019-12-18). "Prefeitura inicia implantação de fossas biodigestoras" [Town hall starts implementing digesters]. Mangaratiba Town Hall (Portuguese: Prefeitura de Mangaratiba) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- Bidegain, Paulo; Pellens, Roseli; Jamel, Carlos Eduardo Goes (July 1998), A Situação Atual dos Espaços Territoriais Protegidos do Estado do Rio de Janeiro: Parte II [The Current Situation of Protected Territories of the State of Rio de Janeiro: Part II] (in Portuguese), p. 110, retrieved 2020-02-16

- Lopes, Monique Oliveira (2014-04-11). Diagnóstico Ambiental dos Rios da Prata e Catumbi e Balneabilidade da Praia: Estudo de Caso em Muriqui, Mangaratiba - Rj (MSc) (in Portuguese). UERJ. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- "Rio em Muriqui é dragado" [River in Muriqui is dredged] (in Portuguese). 2012-12-22. Archived from the original on 2020-02-16. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- "Limpeza no Rio Muriqui" [Cleanup on Rio Muriqui] (in Portuguese). 2015-06-16. Archived from the original on 2020-02-16. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- Assis, Caio (2016-06-06). "Desobstrução do Rio Muriqui" [Deobstructing of Rio Muriqui] (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- "Average Weather in Mangaratiba, Brazil". Weather Spark. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- "Relatório da Qualidade do Ar do Estado do Rio de Janeiro - Ano Base 2015" [State of Rio de Janeiro's Air Quality Report - Base Year 2015] (PDF). Instituto Estadual do Ambiente (in Portuguese). 2016. p. 119. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- "Encerrando a nossa Semana do Folclore, vamos contar a lenda do Vento Vieira" [To end Folklore Week, we'll tell the tale of Vieira Wind]. Fundação Mario Peixoto (in Portuguese). Instagram. 2018-08-24. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- "Curiosidades da cidade: A história do vento Vieira" [City's curiosities: The story of the Vieira wind]. Jornal Litoral (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Mangaratiba. April 2015. p. 12. Retrieved 2020-09-04 – via Issuu.

- Plummer, Todd (2016-08-08). "Artist Mariko Mori Explains Her Stunning Rio 2016 Art Installation". Vogue. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- Guimarães, Ana Cláudia (2016-07-13). "Cachoeira em Mangaratiba (RJ) ganhará 'auréola gigante' feita por artista japonesa" [Waterfall in Mangaratiba (RJ) will get 'giant halo' made by japanese artist]. O Globo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- "Parque Estadual Cunhambebe inaugura trilha adaptada para portadores de necessidades especiais" [Cunhambebe State Park inaugurates trail adapted for the disabled]. INEA (in Portuguese). 2017-07-18. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- Popov, Flávia, ed. (2018-04-02). "És princesinha colossal da Costa Verde". O Hoje.com (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- Guimarães, Saulo Pereira (2019-12-15). "Laranjas e vieiras com 'pedigree' lutam por selo de certificação". O Globo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- Araújo, Helder Rangel de (2018-03-27). "Projeto de Lei Nº 10/2018" (PDF). Câmara Municipal de Mangaratiba (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2020-09-28.

Bibliography

- "Recenseamento Geral de 1950 – Série Regional" [General Recensus of 1950 – Regional Series]. Censo Demográfico (in Portuguese). Vol. 23 no. 1. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. August 1955. p. 94. ISSN 0104-3145. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "VII Recenseamento Geral do Brasil – 1960" [VII General Recensus of Brazil – 1960]. Censo Demográfico (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. August 1961. p. 7. ISSN 0104-057X. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "VIII Recenseamento Geral – 1970 – Série Regional" [VIII General Recensus – 1970 – Regional Series]. Censo Demográfico (in Portuguese). Vol. 1 no. 16. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. June 1973. ISSN 0104-3145. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "IX Recenseamento Geral do Brasil – 1980 – Dados Distritais" [IX General Recensus of Brazil – 1980 – District Data]. Censo Demográfico (in Portuguese). Vol. 1 no. 16. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. 1983. ISSN 0104-3145. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "Resultados do universo relativos às características da população e dos domicílios" [Universe results in relation to population and residence characteristics]. Censo Demográfico (in Portuguese). No. 20. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. 1991. ISSN 0104-3145. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "Estudo Socioeconômico 2003 – Mangaratiba" [Socioeconomic Study 2003 – Mangaratiba]. Estudos Socioeconômicos dos Municípios do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Tribunal de Contas do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. October 2003. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "Estudos Socioeconômicos dos Municípios do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – Mangaratiba" [Socioeconomic Studies of the Municipalities of the State of Rio de Janeiro – Mangaratiba]. Estudos Socioeconômicos dos Municípios do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Tribunal de Contas do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. December 2011. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "Histórico dos Boletins Semanais das Praias da Costa Verde - 2013" [History of Weekly Reports of Green Coast Beaches - 2013] (PDF) (in Portuguese). INEA. 2013. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- "Histórico dos Boletins das Praias da Costa Verde - 2014" [History of Reports of Green Coast Beaches - 2014] (PDF) (in Portuguese). INEA. 2014. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- "Histórico dos Boletins de Balneabilidade das Praias da Costa Verde - 2015" [History of Reports of the Balneability of Green Coast Beaches - 2015] (PDF) (in Portuguese). INEA. 2015. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- "Histórico dos Boletins de Balneabilidade das Praias da Costa Verde - 2016" [History of Reports of the Balneability of Green Coast Beaches - 2016] (PDF) (in Portuguese). INEA. 2016. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- "Histórico dos Boletins de Balneabilidade das Praias da Costa Verde - 2017" [History of Reports of the Balneability of Green Coast Beaches - 2017] (PDF) (in Portuguese). INEA. 2017. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- "Histórico dos Boletins de Balneabilidade das Praias da Costa Verde - 2018" [History of Reports of the Balneability of Green Coast Beaches - 2018] (PDF) (in Portuguese). INEA. 2018. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- "Qualificação Anual Histórica das Praias da Costa Verde - Resultados de Bacteriologia Consolidados" [Historical Annual Qualification of Green Coast Beaches - Consolidated Results of Bacteriology] (PDF) (in Portuguese). INEA. Retrieved 2020-09-05.